| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 11 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Andrew Joron and Andrew Zawacki and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/sobin-intro-by-joron-zawacki.shtml

756 pages. Talisman House. Paper. 27.95. ISBN 978–1584980728.

1

Gustaf Sobin lived in the south of France for over forty years. He had discovered, in 1962, in his mid-twenties, the poetry of René Char, via a Random House translation edited by Jackson Matthews, with a blurb from William Carlos Williams. His encounter with Char’s work spurred the aspiring poet to abandon his native United States, a place associated in his mind with crass commercialism and a Cold War freeze on aesthetic innovation, for the vineyards, cypresses, and olive groves of the Luberon, a mountainous region he believed to be the locus of primal purity and poetic flourishing.

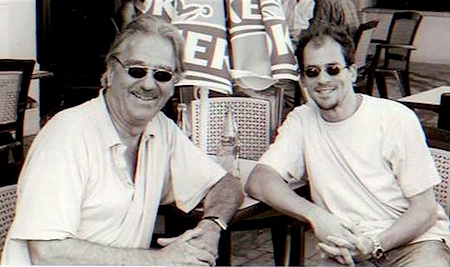

Gustaf Sobin, left, with Andrew Zawacki, France, 2003.

2

Through the intercession of a mutual friend, the young Bostonian was able to meet Char in Paris. As Sobin later recalled, “Char, an immensely warm man of unpredictable humor, urged me to visit Provence. If I admired his poetry so much, he said, I should, at least, see where the poems themselves came from.” [1] Sobin returned briefly to the States to sell his belongings and arrived in Provence in February 1963. With financial assistance from Char, he purchased an abandoned silk cocoonery in Goult, a medieval village in the Vaucluse, not far from where his exemplar lived. Sobin converted the old building into a residence and added, a short walk away, a cabanon containing a modest writing desk and chair, a manual typewriter, a shelf for a few books and dry lavender, a window, a cot.

3

This simple hut, with its small windows opening onto the wide fields of Provence, would serve as Sobin’s singular workspace from the beginning of his apprenticeship to Char until the end of his days. Here, in this writing cabin, over the course of four decades, Sobin produced eight books of poetry, four novels, three volumes of essays, and two books of translation. Gustaf Sobin died in Provence, a few months before his seventieth birthday, in summer 2005.

4

Having lived abroad may, in part, account for why Sobin has often been seen — or unseen — as a somewhat minor, mandarin poet, claiming a venerated group of admirers and apologists but lacking the wider public that many writers, uneasy descendants of Kafka’s hunger artist, often welcome even as they abjure its intrusion. Sobin’s writing, unusually attentive to the natural world, language’s spoors and spirals, and the mysteries that ligature one to the other, is a subtle form of communication that has refused to beg for attention, demanding instead the patient, voluntary hospitality of the reader. This is an exigency not easily heard, let alone answered, by participants in an increasingly careerist American literary milieu, where prizes and pedigrees, university prestige, and divisive politico-aesthetic loyalties have come to dominate the would-be poetic discourse.

5

On the contrary, as Theodore Enslin once lauded, Sobin was an amateur, in the highest sense of the word: a lover of the thing itself. Sobin’s was a lifelong investigation of, investment in, and vigilance toward the tiniest, most peripheral of objects and abstractions; he sought to glorify them like Hopkins, whom he claimed as his favorite poet, and offered antiphons to “the psalm, burnt / to a glass / whisper,” that Traherne had penned with a similarly quiet profile. “My entire work,” Sobin once confided, “might be seen as a transcript of sorts, celebrating margins.” [2]

6

Sobin’s approach to poetry places him not only at the margins of the American literary scene but, even more resolutely, at the margins of language itself. Meaning, for Sobin, is something perpetually blown, scattered, scuttled, gutted, obliterated — yet, at the same time, something incendiary, reverberant, resonant, shimmering. Situated at the very edge of the sayable, Sobin’s poems offer transcriptions of the isn’t — a recurrent word, in his usage, suspended between verb and noun, and caught in the act of contracting against its own negation. More than any other contemporary poet, Sobin possessed a Heraclitean awareness of negation as a form of (re)generation: his insistent return to the instant of the isn’t represents not the stopping, but the starting point of poetic motion. Sobin’s line becomes a “traced erasure,” [3] alive to the vaporous echoes of the null, the naught, the neither.

7

Moreover, the propensity of language to negate being, to stand in place of the thing signified, in the manner of a mirror or a veil (further Sobin keywords), is frequently registered in Sobin’s work as a play of reflexivity, a flexing of meaning against its own iteration (in the later poems especially, this endlessly reflected vanishing point is identified as you, an address to the self as other). Here, the word — as a stand-in for something other than itself — is finally understood to be an index of exile, a vestige or relic of original being: “for language, as you’d learnt, was never more than the arbitrary imprint of a violated silence.” [4] Sobin’s self-exile from his native land thus finds an echo in his poetic practice.

8

Yet, in life and in language, Sobin was at home in exile. Far from feeling alienated from a Kulchur inimical to any notion of reception, “It’s almost an advantage,” he avowed, “living at a distance in which one’s own language is used — almost exclusively — for writing. The words take on a kind of buoyancy, a kind of freshness. They’re free of so much exhausted usage” and “day-to-day attrition.” [5] The poet perceived his adopted home of Provence, with its deep, historical layers of human occupation from the Neolithic onward, as a speaking landscape, as living vestige. The Provencal earth, with its breath of the past, was translated readily into the breath of the poem — the earth as air, indeed. Here, it was possible to go “delving, as you did, for echo,” finding the “impression, everywhere, of aftermath: of having entered, already, an after-world; of muttering to yourself in some kind of after-language.” Not with the intention of preserving the past but rather, by a poetic act, of turning time inside out: “would, if you could, precede vestige. / reach, that is, far enough back that you might begin, finally, projecting forwards.” [6]

9

Sobin’s poetic project is revealed, then, as “the resuscitation of so many suppressed ur-words by the bias of a yet-to-be articulated grammar.” [7] These ur-words, the original Saying, have yet to be spoken.

10

In “A Portrait of the Self as Instrument of Its Syllables,” Sobin describes the formation of his own poetic identity as an encounter, not only with the primal landscape of Provence, where he “read / rocks. Read // walls,” but also with the ur-texts of the poets he regarded as his teachers. Claiming Blake and Char as “my // first masters,” Sobin named myriad other influences, spanning from Wordsworth and the impossibly high Romantic aspirations for poetry and ‘the poet’ to the more recent example of American contemporaries like Michael McClure; “from // Mallarmé” he derived “that / rush // of crushed / shadow, and Shakespeare, that / pearl, its / black // sphericity… ” In this poem, Sobin also cites Hölderlin — but largely in relation to Heidegger, whom Sobin met “for several summers running,” when the German philosopher would come to visit Char. Along with Sobin, the sole American present for the occasion, a small number of French poets and philosophers would gather “in the deep shade of René Char’s plane tree” and listen to Heidegger and his host discuss “a single, lapidary fragment of Heraclitus, say, or Empedocles” for hours. “One could only feel privileged,” Sobin later recalled, “to witness their exchange: two giants discussing a handful of words from the dawn of civilization.” [8]

11

Many of the issues raised by Heidegger’s philosophy would become integral to Sobin’s poetics: the relation between Being and beings; the insistence on language as ontologically central; the fraught quest for authenticity in the face of fear, anxiety, death, and the faceless “they”; the fourfold gathering of earth, sky, mortals, and gods; wariness about the encroaching dangers of unchecked technology; worry regarding historical amnesia and the forgetting of that forgetfulness; the phenomenological play of appearance and concealment; the doctrine of care; and the fundamental human need to build and to dwell. At the same time, however, Sobin’s work is partial to the Lévinasian rejoinder to Heidegger. The Jewish thinker had accused Heidegger’s ontology of a pernicious egoism, a spatial and temporal privileging of the self over its surround, including the human community, and sought to devise an ethics that would instead place the other always already before ‘me,’ relegating the ‘I’ to a posture of respect, of infinite responsibility, even guilt.

12

Sobin’s poems, relentlessly pitched toward someone else, whether in situ or in absentia, privilege possible accords between the first person and a second. His insistence on the poem as a passage, of the poetry volume as volute, seems to have been inflected by the interpersonal repositioning endemic to the philosophical turn toward alterity. For an author, chez Sobin, exists only to usher the poem forward, at which point he disappears, while poem itself is likewise only a vanishing point to a more absolute end: each is “nothing, in itself,” he writes in The Earth as Air, “an otherwise-isn’t, except for the syllables, either side, that channel, sluice, project it forth.” [9]

13

That the poet is finally exempted from the poem hints at a latter-day, secular mysticism, a negative theology recoded for aesthetics. Constantly juxtaposing eternity and the ephemeral, Sobin’s work traffics in paradigms of divinity, while eschewing the presence of any orthodox god. Haunted by an evacuated totality, some deity in default, his poems are imbued with what, speaking of the late painter Ambrogio Magnaghi, he called a “lingering religiosity.” [10] This imperative to develop a religious surrogate is hardly specific to Sobin, who warranted his tendencies with examples from antiquity. “Since at least the outset of the Neolithic, ten thousand years earlier,” Sobin said in a late interview, “human societies have addressed — in supplication — invisible auditoria. Have basked in the radiance of some form of immanent response.” [11] He considered this hopeful, albeit withheld reply as the nonetheless “indispensable complement to an all-too-precarious existence on earth.” While the divine cosmology and its assurances have “undergone eclipse,” thereby having “deprived us of our most privileged form of address,” Sobin was adamant in asserting that

14

What hasn’t vanished, however, is the need — call it the psychic imperative — that such an address exist. Long after the addressee has vanished, after the omniscient mirror has dissolved and its transcendent dimension been dismantled, demystified, deconstructed, there remains — I insist — that psychic imperative deeply inscribed within the innermost regions of our being. We can’t do, it would seem, without something that isn’t… Only in the poem, I find, in so many stray bars of speculative music, can that trajectory still be traced.

15

Whether Sobin’s brand of ‘religion without religion’ hails from a quitted Christianity, as with Heidegger, or from the fraught Judaic heritage implied by Paul Celan’s tragic invocations to “you,” Sobin declared no affiliation with any established denomination. Indebted to Saint Augustine and to the Zohar, to Meister Eckhart and Martin Buber alike, Sobin’s writing honors devotion wherever it is practiced.

16

The most obvious and eccentric formal tendency in Sobin’s verse is what he termed its “vertical tracking,” or its impetus to spill, in thrall to gravity’s pull. This laddering of the lyric was “influenced by film,” he once conceded, where “cadence is determined by an inexorable movement downward,” one frame replacing another. More usually, though, Sobin’s impulse to erect his poems earth- and skyward hailed from a commitment to the physical world and its organic processes: “don’t write a poem: grow it,” he remarked, “the poem grows out of the poem, not out of one’s own, particular intellect.” [12] Sobin saw his compositional method as “natural” and “innate,” like training a vine, rather than “intellectually acquired,” and trusted that breaking with linear prosody meant a divorce from positivist thought. [13] Indeed, phrases in Sobin’s semantics commonly begin without capital letters, which he argued would “set up a tiny, typographical hierarchy” that was “slightly imperious,” [14] and many lines lack a subject altogether, beginning instead with a verb, to indicate how the universe verses itself.

17

In his “A Few Stray Comments on the Cultivation of the Lyric,” Sobin insisted that “the poem is verbal, rather than nounal,” that it should render nouns “light and evocative,” should “verbalize” them. [15] Like Emerson, he vaunted transition over stasis, in pursuit of a “discourse of continuous becoming,” but his poems do not neglect tangible stuff or reject words that, in their tactility, slow or stagger a poem’s linguistic rush. [16] Sobin valorized Oppen’s “focused intensity” toward “investing the particular with its all-too-lost significance,” [17] and in Black Mountain and Objectivism he learned to be “scrupulously mindful of particulars, discreet if not downright self-effacing in regard to the personal self, and charged with an innate faith in the power of language as a vehicle of revaluations.” [18] There is as much ‘against’ in Sobin’s work as ‘toward,’ as much bunching, clotting, and interruption, à la Celan’s constricted nominal constructions, as ‘unto.’ This oscillating, “catch- / flow” duality colludes with his recurrent tropes of respiration, mirroring, lovemaking, potential and kinetic energies.

18

Some of Sobin’s formal proclivities, as he happily admitted, were less “innate” than learned. He credited Creeley, for example, with instructing him in how to breathe, to turn or enjamb a line, rig the poem as a “vertical gesture” cascading and terracing downward, rather than spanning across. [19] But Sobin honed this formal gauntness to a radical degree, webbing the page to where individual morphemes snap like a brittle branch in winter, or else bloom as a flower unfolds in spring. Linguistic anthropologists such as Benjamin Lee Whorf and Edward Sapir had showed Sobin, in his own staccato music, “how the / least / shift in syntax, tense- / perception, would / re- // set the / heavens.” [20] His ambition and humility alike were aligned to such a recalibration. This generative process is frequently figured sensually, often erotically, as the poems lavish among intertwined bodies, seeds, germination, liquid and spasms, blowing and swallowing.

19

Yet alongside incarnated desire and celebrated corporeality, Sobin is never far from asceticism, either, the relinquishment of identity, a reduction to what is “blanched” and unpretentious — the minimal necessity. Language as effulgence, caesura as severest praise: these are the extremes between which Sobin’s poems wander, now in obsessive concentration, now rapt to the parenthetical. The vocal thrust is up- and outward, as exhalation rising, air returning to air, even as the written tumbles, bound for the ground, as an excavation, a mode of depth and of density. A centripetal graffiti, then, married to centrifugal song.

20

To the extent that Sobin conceived writing as obeying “an inherent tendency within language to unspell, unspeak, divest itself of its own nomenclature in an attempt to touch upon the untouchable, utter the unutterable,” [21] his “Transparent Itineraries” prove an intriguing exception. Cutting through and across individual books, stitching the volumes together even as they fray the very notion of a discrete book, the “Transparent Itineraries,” which Sobin began in 1979, are a mostly contiguous string (there are none for the second half of the 1980s) of annual poetic sequences that seek not, as in his other lyrics, to move organically “from a place, a locus, a set of material circumstances, to a proposition,” but rather to assemble the season’s leftovers. [22] Oriented horizontally, less fractured or intuitive than his lyrics, the series is conceptually informed by Duncan’s “Passages” and “The Structure of Rime,” except that Sobin engaged in a conservationist mosaic, recycling the year’s compost, collaging a poem as an archive of remaindered matter.

21

If Duncan had bequeathed Sobin a notion of language as Orphic, ontological source, of poetry as an act of “air, that / ayre exultant,” [23] the “Transparent Itineraries” claimed their start in Sobin’s own, otherwise failed fits and starts. “Essentially ephemeral in nature,” he said of the series, “each passage lasts exactly the length of its implication: its ‘sign’… One elicits another, each linking — transparently — with the next, as the poem moves across the broken landscapes of the experiential.”

22

Marking yet another procedural departure, Sobin’s later poems increasingly partake of extended intellectual, if not academic, exploration. “Reading Sarcophagi: An Essay,” as the latter part of its title announces, traces half a millennium of history to Constantine’s conversion, spanning eleven pages and featuring endnotes, signaled by number within the text. Similarly, the even longer “Late Bronze, Early Iron: A Journey Book” examines the emergence, between 700 and 550 B.C., of the mercantile exchange system. Reaching less for the ineffable than for an irretrievable history, many poems, from Towards the Blanched Alphabets onward, eschew a seminal object of meditative contemplation characteristic of Sobin’s earliest, haiku-like lyrics, and instead pursue, with increasing abstraction and logic, the decline of entire societies.

23

These poems, along with others like “Barroco: An Essay” and “On Imminence: An Essay,” were written more or less concurrently with a research project on Gallo-Roman antiquity that would eventuate as Luminous Debris: Reflecting on Vestige in Provence and Languedoc, one of Sobin’s best loved books. Ostensibly a collection of anthropological essays, the constituent meditations are as ‘poetic’ as some of the later poems are rigorously ‘essayistic,’ and while written in prose they are nonetheless, like the lyrics, devoted to what Sobin termed a “vertical reading” of southern France.

24

The present volume collects all the poems that Sobin published during his lifetime, in eight full-length books, as well as those residual lyrics (placed in an order agreed upon by his daughter Esther Sobin, publisher Ed Foster, and us) that constitute about half an untitled, final manuscript. A late bloomer, Sobin completed his first book, Wind Chrysalid’s Rattle, at the age of forty, and it would not appear until five years later, from the Montemora Foundation, as a supplement to their magazine of international poetry and poetics. Montemora would publish his second book, Celebration of the Sound Through, as well.

25

Meanwhile, art critic, novelist, and fellow expatriate John Berger had introduced Sobin’s work to Charles Tomlinson who, in turn, recommended it to James Laughlin. The founder and editor of New Directions ran Sobin’s poems in numerous numbers of the annual New Directions Anthology in Prose and Poetry, eventually publishing his next trio of books. After Laughlin’s death, Sobin was released from the New Directions list, publishing the four books comprising his later career, including a selected poems, with Talisman House.

26

For better or worse, this Collected Poems does not take into account a dozen or so chapbooks and pamphlets, most of them limited editions, occasionally letter-pressed, that have, since the mid-1960s, been printed in America, England, and France by Arcturus, Blue Guitar, Cadmus, Grenfell, Oasis, PAB, and Shearsman. Nor does this book reprint Sobin’s fugitive journal publications. There were compelling reasons to include all these texts, exhaustiveness being the primary one, and a scholarly edition of Sobin’s work, noting variants, initial publications, and less ‘definitive’ writings, should certainly be assembled someday. In the interest of making his major poems available to readers without delay, however, we have opted, deferentially, to reproduce here all the work Sobin considered worthy of book publication, whatever authority his judgment might convey. We hope the devoted reader, following Sobin’s insistence that poetry is an intimacy escaping category and rational ‘completion,’ will seek out on her own those texts that have evaded this volume, as small, radiating signals that remain at large for now.

27

His literary papers are now housed in the Beinecke archive at Yale — an appropriateness that Sobin, who meticulously catalogued extant drafts and correspondence shortly before his death, would appreciate. Half a century earlier, as a Brown University undergraduate, he had worked his way through the Eliot and Pound holdings, among many others, in the Gertrude Stein collection in nearby New Haven. So in some ways his poetry has returned to its archival origin.

28

Needless to say, this volume does not include Sobin’s quartet of novels, published over a decade, the most successful of which, by far, has been The Fly Truffler. First published in England in 1999 and in the U.S. the following year, the book’s translated editions have appeared in Germany, The Netherlands, Portugal, France, and Taiwan. “If poetry could be called the realm of the unexpected,” Sobin once ventured, then prose “is that of the plan, the foreseen.” [24] His fictions might be considered the level, deliberately constructed counterpoints to his more natural, vertical lyrics. Sobin’s further experiments with narrative, scarce or at best oblique in the poems, manifested themselves in a series of short stories and a co-authored children’s book.

29

His translations of Henri Michaux are available from New Directions in a boxed, signed, limited edition, while his renderings of René Char into English were published last year by Counterpath Press, as The Brittle Age and Returning Upland. The second volume in Sobin’s planned triptych of anthropological essays, Ladder of Shadows: Reflecting on Medieval Vestige in Provence and Languedoc has recently been published by the University of California Press, and Counterpath Press has issued the third, never finished book, under the title Aura: Last Essays.

30

Sobin liked to think of his own itinerary, in poetry and in the poetry, as having begun with “becoming,” progressed through “being,” and having concluded, precisely without conclusion, in “non-being.” That seems an appropriate trajectory for a poet so deeply concerned with the modalities of existence and extinction. We are, he worried, at the end of history, but only that it may yet begin once again, renovated by none other than the poet. Who, in a final act of self-sacrifice, would not live to witness the transformation that his words, of their own will-to-powerlessness, would work. The poet, touched by the “null,” the “no-breath” that the poem carries “within,” himself would become nothing more — and nothing less — than a noble passage; he would pass. While “poetry,” Sobin said one afternoon near Avignon, “cannot but survive.”

[1] Ed Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin,” Talisman: A Journal of Contemporary Poetry and Poetics 10 (Spring 1993): 38. The number contains a feature on Sobin’s work.

[2] Tedi López Mills, “Epilogo, Entrevista con Gustaf Sobin,” in Matrices de viento y de sombra: Antología Poética 1980–1998, edited and translated by Tedi López Mills (Mexico City: Hotel Ambos Mundos, 1999) 176.

[3] “Late Bronze, Early Iron: A Journey Book,” in the present volume.

[4] “Transparent Itineraries: 1994,” in the present volume.

[5] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 36.

[6] “Late Bronze, Early Iron: A Journey Book,” in the present volume.

[7] “Transparent Itineraries: 1999,” in the present volume.

[8] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 36.

[9] “The Earth as Air: An Ars Poetica,” in the present volume.

[10] “The Miracle Depicted,” Ambrogio Magnaghi (Milan: Skira, 2004) 11.

[11] Leonard Schwartz, Interview with Gustaf Sobin, Verse 20.2&3 (2004): 110.

[12] Gustaf Sobin, “A Few Stray Comments on the Cultivation of the Lyric,” Talisman 10 (Spring 1993): 41.

[13] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 31.

[14] Mills, “Epilogo, Entrevista con Gustaf Sobin” 178.

[15] Sobin, “A Few Stray Comments on the Cultivation of the Lyric” 43.

[16] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 34.

[17] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 29.

[18] Mills, “Epilogo, Entrevista con Gustaf Sobin” 181–182.

[19] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 31.

[20] “A Portrait of the Self as Instrument of Its Syllables,” in the present volume.

[21] Schwartz, Verse 112.

[22] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 26.

[23] “A Portrait of the Self as Instrument of Its Syllables,” in the present volume.

[24] Foster, “An Interview with Gustaf Sobin” 34.

Andrew Joron

Andrew Joron is the author of Trance Archive: New and Selected Poems (City Lights, 2010). Joron’s earlier poetry collections include The Removes (Hard Press, 1999), Fathom (Black Square Editions, 2003), and The Sound Mirror (Flood Editions, 2008). The Cry at Zero, a selection of his prose poems and critical essays, was published by Counterpath Press in 2007. He lives in Berkeley, California, where he works as a proofreader.

Andrew Zawacki

Andrew Zawacki is the author of the poetry books Petals of Zero Petals of One (Talisman House), Anabranch (Wesleyan), and By Reason of Breakings (Georgia). Recent chapbooks include Lumièrethèque (Blue Hour), Glassscape (Projective Industries), Roche limit (tir aux pigeons), and Bartleby’s Waste-book (PS). He is coeditor of Verse, and his translation of Sébastien Smirou, My Lorenzo, is forthcoming from Burning Deck.