| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Alistair Noon and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-goodland-rb-noon.shtml

Giles Goodland

What the Things Sang

reviewed by

Alistair Noon

112pp. Shearsman. GB £8.95. 9781848610545 paper

Giles Goodland

1

Among the many qualities of this book is its interest in human existence as a whole. It kicks off with a quadruple hit of couplets:

2

The map to the finger:

the journey to here starts everywhere.

The phone to the ear:

his name changes radically over the next few minutes.

The spoon to the mouth:

forces we have no contact with determine breakfast.

The glasses to the page:

no one can see the eye evolving.

3

Douglas Oliver used the term “sublime literal” to describe some of what is going on in British poetry. [1] It’s a term I take as describing a poetry that is both direct and demanding at the same time. With its lists, permutations and aphorisms, What the Things Sang represents a variant on this, something like the sublime linguistic: playfully demanding of our concentration, yet getting us elsewhere.

4

In this collection, permutation is used to approach the general and transcendental: avant-garde technique for the grand lyric gesture, as concrete poetry meets metaphysical aphorism. Goodland is unusual as a poet in combining the influences of experimental and lyric poetry, and one of the few Anglophone poets I know of to transfer the techniques of the twentieth century avant-garde into forms that the rest of the column might just be able to do something with.

5

Isn’t this a valid consideration? Experimentation and pushing forward are valid too, but some kind of compromise or at least shaping to default tastes seems a socially worthwhile thing for at least some poets to be doing. Who knows, they might even get quoted, as this book frequently invites this reader to do.

6

Giles Goodland’s preceding two books, A Spy in the House of Years and Capital, bear on a reading of this latest collection. They too were attempts to get to the world as a whole, by means that reappear in modulated form in What the Things Sang.

7

A Spy in the House of Years was a sequence of one hundred sonnets, one for each year in the twentieth century. Each sonnet is composed entirely of quotations from publications from the year in question, ranging from the House Drainage Manual (1903) to the International Review of Applied Linguistics (1998). Here is ‘1915’, ridden with nationalism and the trenches:

8

I have often picked up on the surface of the camp pieces of old root-eaten human bones

bits of brilliant stone, crystals and agate and onyx, and petrified wood as red as

the intelligence of his soil. The sovereign ghost

was in a violent state of excitement, and blew a police whistle

9

These collaged cuttings of text derive respectively from the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, a book called Song of Lark, something about someone called Blanche McCarthy, and the Daily Mirror.

10

Capital was another shot at getting the whole world in, again with poems composed entirely of quotation: the quotational aspect of (post)modernism taken to its extreme, an ultra(post)modernism in which the shattering of the text into texts is utterly marked up,. The guiding lights are the metaphors we live, think and speak by. The quotations in ‘Liquid Capital’, for example, all have to do with water and flow: ‘… Detroit’s gains, fuelled by higher car prices and higher unit sales, haven’t trickled down’ … / ‘urine voided by the patient in the normal way is collected and centrifuged.’

11

Some writing wisdom has it that one writes best about what one knows and has experienced oneself, or at least draws on it to some extent. Whole schools of poetry have been founded on this premise. And case studies have value: a sonnet can be significant, even if its connection with the world is one of depth rather than breadth. But if contemporary poetry doesn’t now and again have a go at capturing the world as a whole — of which, patently, no individual can have full knowledge — it can be asked what kind of a discipline it is that confines its insights to discrete phenomena.

12

One well-known self-professed attempt in 20th century poetry to capture the whole world, or at least a large part of it, was the Cantos. Pound’s strategies included quotation, translation, adaptation, narration, collage, montage. For all the High Modernist discourse of objectivity, though, Pound’s subjective interests in particular episodes and elements of world history and literature clearly steer the composition (‘improvisation’ might be more accurate, given Pound’s own later doubts about its structure). The idea, propounded by E.P. himself, that the author might have hit on particularly representative motifs in the life of humanity requires a belief in the cyclical nature of history and a faith in the prophetic and analytical powers of the poet.

13

The geographical and cultural scope of the Cantos is much wider than the models Pound aspired to, namely Homer and Dante, but Pound’s methods still represent more a modification than a replacement of the traditional epic poem: the epic poems of the past serve as a foil for Pound’s work, using the strategies mentioned above. The Cantos, however, have a credibility problem.

14

They evolved in recent memory and in a time for which we have so much more documentary evidence than for Homeric Greece or Dantean Italy. Moreover, the deliberate fragmentation of the narrative means that there is no guiding story inviting and inciting us to suspend any disbelief. At the same time, Pound seems to see the historical and political aspects of the poem as grounded in reality: famously, his professed aim was to tell the Tale of the Tribe. Consequently, the Cantos, or at least their heavily historical parts, invite readers to ask the author whether he is really quite sure about his data. Whatever other qualities the text has, in its claims to be presenting reality it has the uncomfortable quality of the docudrama: both sell themselves as fact but have strongly fictive aspects.

15

Spy and Capital, post-something-or-other long poems, get round these problems by taking as their material, on one level, simply text related to many aspects of the world — political, economic, cultural, domestic, scientific, journalistic, medical, historical, if limited to and filtered through the English language — which is something that one mind really can engage with and experience. By flagging up the textuality of the materials there is no presumption of objectivity beyond the fact of these materials existing out there in the world.

16

Two notions are turned on their heads. One is the concept of chopped-up prose, as a criticism of either free verse in general, or badly done free verse. The two books turn this around into a positive concept: chopped-up prose is the working method, exactly what the form of the poems is supposed to be. Another flip is performed on the idea of difficult poetry being difficult because of the “references” (this is often a confusion of contingent difficulty — recognising or not recognising what’s there in the text — with procedural difficulty — knowing or not knowing what you can do with the text). This is turbo-referential poetry: the text is composed only of quotations.

17

But the poems are not hermetic: instead, they heighten and sharpen the outward-looking aspect of poetry, referring out to the numerous texts from which they are drawn. It will probably be a while yet before a PhD student traces all the quotes in context, but the simple knowledge that the quotations are drawn from multifarious sources is enough to create a residue of referentiality.

18

These previous two books of Giles Goodland’s demand reading strategies associated with high and late modernist texts: willingness to supply connections, interpretative alertness, tolerance for partial non-understanding. But atypically, their building block and capital, the truncated quotation, is an element which is in and of itself fairly open to less marked forms of reading. From where you’re standing you might not be able to see everything that’s in the room, but the door’s been left wide open.

19

In Capital especially, the effect is of standing in waist-deep seawater while the tide washes in, rising up with each wave, staying there a moment, wanting to stay there longer, while the water brings you down again, waiting for the next wave. There may be initial shock at the coldness of the water, but you should soon warm up. The text is only a sample, of course, but as ‘Zero Capital’ puts it: ‘The marginal utility of unaccessed data is zero… ’

20

Spy and Capital represent significant expansions of the found-text technique. We’ve had reshapings of single texts from Charles Reznikoff, Gael Turnbull and many others. High Modernist works beside the Cantos — The Waste Land, Paterson and “A” — have sections that are more or less found. One could pursue the argument that, as poetry is made up of language and language use has elements that are given, if manipulable, an element of foundness pertains to all poetry.

21

But splicings of multiple sources in a more, well, coherent form than Pound’s (“I cannot make it cohere”, he famously complained in the last Canto he completed before his death) are new — John Bloomberg-Rissman’s ongoing mammoth Zeitgeist Spam project is another contemporary example. Such splicings realize the refrain in Tom Phillips’ seminal treated Victorian novel A Humument, a found and shaped text par excellence, of “only connect”.

22

Where Spy and Capital used quotation as a resource, What the Things Sang is a resource for quotation. The book is permeated by a kind of Imaginary Foundness: many lines feel like they haven’t been said before, but should have been:

23

A person is slower than a flower

…

There is a law or a war against this

…

When I cycle to work everything else follows as a recurrent dream

…

modernity: everything travelled faster but no one arrived

…

war extends language by other means

…

death an accumulation of full stops

24

I’m not cherry-picking here, at least not much: these quotations are more examples than exceptions. They gain full force in context and within the structures and patterns of the poems, determined by various kinds of form and order. One is typography, as in visual poetry and graphic design. Line and thought are ordered by the length of the printed line:

25

I a small title in another person’s library

in the way out

this a meaning which cannot name itself in language

26

The text continues in this way with the words on the left hand side gradually increasing in length.

27

Another determinant — again drawing on but expanding the techniques of concrete and visual poetry — is the alphabet. The alphabetically structured poem is something of a stock-in-trade of the post-futurist strand in experimental poetry: Bob Cobbing’s ‘ABC in Sound’, Valeri Scherstjanoi’s ‘Azbuka’ (the Russian Alphabet), Franz Mon’s alphabet poems, and is still productive in digital poetry. [2] But in What the Things Sang, the alphabet is used to structure propositional content:

28

adjective, correct yourself

animal, celebrate language

artist, return to world

baby, sing the shapes back to sleep

bed, replace the same bodies nightly

29

(the poem continues in alphabetical order of the things or people addressed for another 145 lines).

30

Punctuation is also played around with in a distinctive way. Full stops can and often do denote not the end but the middle of a line (this is a technique carried over from Capital). The shape is clear though: this isn’t a loose free verse permutation applied to the sentence, but stringency closer to that of fixed forms.

31

The result of these tactics is to give individual lines an atomistic, discrete feel to them, thus making them quotable and aphoristic. Some are paradoxes (‘If language would explain everything — we would not understand it’) or secular koans (‘the past is like the future, unlike the future’ ; ‘how many whispers make a shout?’). They become a series of assertions rather than an argument: the coherence of the poems is in the visual form and the structure rather than a tracing of direct relationships between the lines.

32

Permutation is fundamental to poetic form, but gets applied differently in different poetries: consonants in Anglo-Saxon poetry, vowel length in Romance languages, perceived stress in Germanic languages, syllable number in Japanese, tone patterns in Chinese. Goodland permutates sense and grammatical structure. If permutation implies variation, it is dependent on regularity, and this is provided here frequently in the form of the list.

33

The list, too, has a long history in poetry, often within the epic tradition: warriors on the shores of the Aegean, sinners in the circles of hell, pilgrims on their way to Canterbury. One thing which stops Goodland’s lists from becoming claustrophobic is the breadth of reference, often literary, as in the nods to Yeats — ‘The wild swans at Coole are flights of fancy’ — and Basho — ‘The narrow road to the deep north is the M1.’

34

The lists are relentless waves, but they are different waves, shallows and troughs, warm and cold, long-distance currents, El Niño effects. The list form typically highlights the grammatical structure of the line: subject, verb, object, making the lines resemble in their unfussiness a theoretical linguist’s constructed sentence for a tree diagram. By another kind of flip though, what we get are not the constructs of a Chomsky experiment — sentences deliberately denuded of semantic and pragmatic aspects for the purpose of analysis — but rich, aphoristic paradoxes, statements, questions, answers.

35

Proof is provided of Chomsky’s wonder at the number of novel sentences our brains can produce. Some poems have something of the search results of a concordance programme. The strategic and systematic punctuation makes the lines of many of the poems feel like fragmentary quotations, a self-pastiche or development of the techniques employed in A Spy in the House of Years and Capital, the latter referred back to in the line ‘to write is to interpret Capital’. They also frequently have — ironically — the pithiness of the PR department of Capitalism, namely advertising: ‘milk is your future bones.’

36

Has the idea of the self been eroded and are we left here with the bare, hard outcrops of language? What Goodland’s permutational poems have which sets them off from canonical concrete poetry is a new kind of texture and real depth. Neither the linguistic surface of concrete poetry nor the narrow focus of some post-Larkin mainstream poetics. The voice, such as it is, seems both grand and unpoetic at the same time. This seems to me like basic research, in the sense of research aimed at fundamental principles rather than specific applications.

37

Take the line ‘Free the dinosaurs from their stones.’ In the typical über-simplicity of the diction this is reminiscent of concrete poetry, which may provide space for the reader’s own brain activity, but can also run the danger of quick exhaustion. It also has both individual and socio-political aspects: the exhortation implies a speaker. What is this line? A reaffirmation of the value of science? A parody of emancipatory politics?

38

The permutational techniques are not applied for lack of ability or willingness to “develop an argument”. There’s too much connection to the really existing world here for that. In these poems we’re within but not limited by language. A famous counter-example:

39

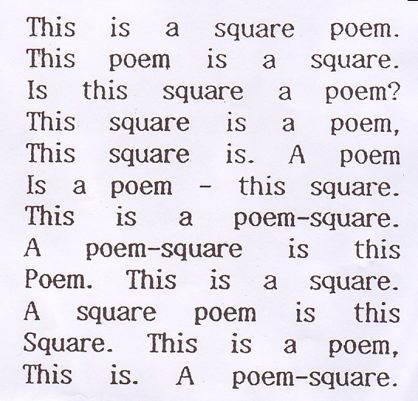

Cobbing’s ‘Square Poem’ is more than simple permutation: it is open to different interpretations and offers the sense of an argument. But in its self-referentiality it stays, inevitably, within the realm of language and aesthetics. Concrete poetry typically isolated visual, auditory, and sometimes semantic aspects of language from the pragmatic, the way that language is actually used in everyday discourse. But instead of revolutionizing poetic sensibility as a whole, as some of its early practitioners such as Eugen Gomringer aimed to do, concrete poetry now occupies a stimulating but limited niche, in which language and aesthetics become the default subject matter.

40

The postconcrete poems of What the Things Sang take us outside and beyond the linguistic world of the text, and in the era of soundbite, advertising slogan, mission statement (‘advertising occupies the place of art’, one poem notes) seem authentically contemporary. If the Cantos were Pound’s attempt at the Tale of the Tribe, these poems represent an attempt at the Made-up Sayings of the Tribe, an imaginary Dictionary of Quotations, Blake’s ‘Proverbs of Hell’ for the modern age.

41

We get wit and linguistic inversion as a way of seeing the world anew — ‘Global warming as matched by personal cooling’; ‘We are necessary to triangulate the stars’ — and the linguistic version of the Selfish Gene theory: ‘Language musters together some people so that it can be talked.’ The cliché is scooped up, a clod of language that becomes soil for a new growth: ‘The start of something beautiful is the end of the affair’; ‘The mist of time is the fog of war.’ There’s a sharp sense of Language as Capital. And what might end up as a groaning pun has a serious sense to it: ‘mistrust made of mist and rust’.

42

The remains of John Donne are exhumed and a clone is made from the DNA, and attends a Writers Forum workshop. The result is a pastiche of the Renaissance simile: ‘as when a large amoeba hunts a small one / as when a train is removed from the timetable’. Goodland approaches words and phrases head on — time, memory, world, stars, dream, flower — that the self-respecting late post-Romantic poet tends to leave to the stock of Fridge Poetry Kits, and revalorizes them: ‘if time is the rain at the end of the rainbow — it’s the wind in the hair’.

43

Whilst I don’t necessarily advocate the formation of Goodland Societies (along the lines of the Robert Browning Societies in the nineteenth century) to divine the thoughts of the bard, there is a great deal here that invites reflection line by line. Not every line has the same pay-off, but the whole thing is a valuable accumulation. Its combination of linguistic and ideational defamiliarization with simplicity of diction parallels that of Kafka. If these techniques catch on [3], we may see the emergence of the adjective ‘Goodlandesque’.

44

The preceding comparisons notwithstanding, nothing I know of is really like this book. I will stick my head above the parapet and say that if in one sense A Spy in the House of Years was the book of the (twentieth) century, in another sense What the Things Sang might be the book of the (last) decade; at the very least, a ground-breaking book of poetry in English.

[1] Essay on JH Prynne’s “Of Movement Towards a Natural Place” in Grosseteste Review vol 12, p. 96: “.but a poetry can reach beyond analogy, all the same, towards a kind of sublime-literal". Thanks to Simon Perrill, Peter Riley and Kelvin Corcoran for tracking this down for me.

[2] http://archives.chbooks.com/online_books/dreamlife_of_letters/

[3] See e.g. http://toddswift.blogspot.com/2009/08/new-poem-inspired-by-reading-giles.html

Alistair Noon, photo by Clare Jephcott

Alistair Noon has published chapbooks with Oystercatcher, Penumbra and, most recently, Longbarrow Press (Animals and Places, 2010), as well as translations of Pushkin (Longbarrow) and Monika Rinck (Barque). His translations of Osip Mandelstam are forthcoming from Leafe Press, 2011. He lives in Berlin.