| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 6 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Will Cordeiro and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-glenum-rb-cordeiro.shtml

Lara Glenum

Maximum Gaga

reviewed by

Will Cordeiro

Action Books, 112 pages, soft cover, US $16.00 ISBN 978–0-9799755–3-0

1

Lara Glenum’s Maximum Gaga is a schizophilic, pataphysical ricochet of puns and word-play, allusions and collusions, superimposed into an ever-disintegrating narrative about the ever-disintegrating nuclear family. The title alone is a ground-down zero degree of sonic fallout: an homage to Lady Gaga with a stage-whisper to Olson’s Maximus Poems. The Gaga of the title also echoes Gigi, the nickname of the anime and manga character Magical Princess Minky Momo, who is the protagonist in the book’s first (unspeakable) act. Gaga, at once connoting infantilism and infatuation, is excess taken to excessive measures, silliness brought back to the sublime via the grotesque sillyhow that anoints a blesséd newborn, a holy fool that’s not only touched but, in this case, fondled — just as Glenum’s macabre, poetic “cauling” indulges in oracular bumps, grinds, burps, and babytalk.

2

Lurking, or lurching, inside all this Trojan horseplay, however, is a telepathic vision of human beings as a televised Grand Guignol (de)composed by meta-meat sock-puppets and jury-rigged ragdolls, which, off the hook itself, nevertheless never lets its readers off their hooks. As we lose our grip on these lyrics, the book’s gaga gag-joke chokes us into an unseemly, disoriented laughter, kicking out the stuffing our consumer dreams are made of, and splitting us apart at our very seams.

3

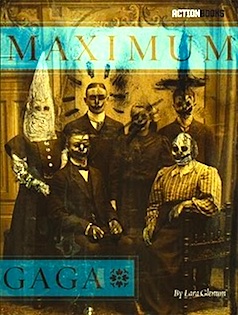

The cover art by Mia Mäkilä features a sepia-toned photograph of a Victorian family, which has been mutilated with white-out and a Sharpie into skeletons and grinning demons, one impaled by an overturned cross, another tuned into a hooded Klan member (with hints of Hugo Ball’s cabaret dunce outfit), and a third sporting a mask that transforms her into an amalgam of an executioner and a luche libre wrestler. Grafted upon all this graffiti one can detect fuddling smears and fingerprint smudges, cum-stains and crayon marks straying outside any semblance of a line. The image conjures up the palimpsest of cultural myths that will be both written over and overridden by Glenum’s poetic congeries, which engender endless metamorphosis of Ovidian propulsions, a touch-and-go of vividly accelerating forms and deformations.

4

The first act of what may be described as this “water-closet” drama involves a love triangle between Minky Momo, Mino, and a creature called the Normopath. Any linear plots or traditional geometry such as a triangle (including the Bermuda triangle of the mons veneris) begins immediately to get hairy, corkscrewing as soon as the twisted Normopath, Minky’s neighbor nicknamed “The Rooster”, begins “maling / protoplasmic goo into my bone pagoda,” stuffing her male-box with invites to “Mr. Humpty’s Charity Ball” where the “squealing verbs” will “be tied to signposts.”

5

Language itself becomes the site of giddily apocalyptic S&M and costume play, such exquisite cockamamie being as rare as hen’s teeth. Meanings meander in an esemplastic imaginarium where “signposts” puns on the idea that any referent can be definitively tied down while, simultaneously, submitting to the titillation of such bondage even while knowing there are no safe words. The puns get so dizzying one wonders whether the Normopath at the “Post Orifice” is a jibe at that crowing Nobodaddy, Norman Mailer.

6

At any rate, the Normopath is a monster (in all that word’s etymological and vernacular prodigality, which includes Lady Gaga’s name for her groupies) who commands, “Devour yourself,” perverting everything in his path by insisting it becomes self-consumable. Yet, this cackling poppycock of a boogie-woogie-man teeters on the verge of collapsing in toothless fear when confronted with Minky’s vagina dentata as she gets eaten inside and out.

7

Minky, all her fetish gear and freaky get-ups undone by the Normopath, flies out of her pile of costumes, shooting into the “Normopath’s “ammo-sucking face” then “stretches her labia around her body / like a cocoon and zips herself inside.” Refusing finality, the refulgent refuge of the larval Minky is to costume herself in her own genitalia like a body bag, as if digested by her own cooch, a dead sexy social butterfly retreating into her “other” mouth to pupate into a spangled showgirl. She is simultaneously sealed-off from phallic intrusion in her molting chrysalis and able to extrude silky new molten fabulations.

8

The second act involves a drama at court — and a courtroom — in which the classical myths of Pasiphaë, the Minotaur, King Midas, Icarus, and Dedalus are desecrated into a stage show that features King Minus of Catatonia and his Beckettesque rock-band of hobos (Icky and Ded), who resemble the Insane Clown Posse, versus the glamorpuss Queen and her high-flying, fly-girl stunt double who attempt a putsch. Such hi-jinks are literally a burlesque, producing humor through an incongruous retelling of serious subject matter in colloquial or comic language. Slang gets slung and spoonerisms fork every-which-a-ways in prickly, full-body embraces.

9

When Icky “strapped on / prosthetic wings,” he at once becomes masculinized with a “strap-on” and re-feminized since the wings are also fake labia majora. Eventually he falls into the “see,” to be devoured by “Poseidon’s Trannie Mermaids” and “dislodged from all mythology.” The poems eviscerate their sources, as the raw material of classical texts are defaced and rubbed rawer: Icky’s orgasmic experience with anal beads, for instance, is described as “My spine being pulled out my / asshole : like a string of diamonds.”

10

Much play is also made over Pasiphaë’s cow costume, the patriarchal garb of insult to the female now re-appropriated as battle armor in the war of the sexes, which becomes the “Miraculating Machine” — at once a giant vibrator and lactating sprinkler system; an electric chair and a golden calf; a language factory and a glory-hole; a delirious Deleuzian war machine and Duchamp’s Large Glass, broken and stripped bare; the plot’s hymenal deus ex machina and a mechanical bull in this cock-and-bull story in a china shop.

11

We are told, on page sixty-nine nonetheless, that the “Miraculating Machine” stands “outside all mimesis & / therefore, outside all desire.” The reader gleefully loses his/her way in the tale’s labyrinth, a maze of Merz, which threads through “linguistic sewers” and “fields of wiggity-wack” that write (and wrong) an ever-writhing body. Instead of any straightforward narrative we are given the silly-putty-like substance of pure myth, which twists with continual turns of phrase. Instead of being confined to any genre, the satiric mixed-bag of tropes both high and low congeal but never wholly gel, tripping out and gushing up into lubricious semiotic and clitoral mucilage.

12

The final section of the book contains an appendix of assorted “Secret and Suppressed Documents,” which further suppurates the body of the text by teasingly juxtaposing the “official” narrative with the always proliferating other accounts. These documents become a “loose” canon revealing the open secret that the story, purportedly intact and monumentalized, has an aversion to the other versions of it that are still in the act of becoming. Once the mythic metamorphosis has been set in motion, no one can stop its contamination: the juridical, phallologocentric narrative is contravened by the hidden “testimony”(punning on testes) of the ballsy Queen, whose diaristic jottings are an écriture feminine, which comes as the book’s standing ovation and, perhaps, stand-in for ovulation.

13

The Queen declares that “Each part of my body / was ultimately alarmed,” an image which oscillates between a vibratory climax and a body locked down and installed with a panoptic security system. The Queen’s stunt double may have performed all the Queen’s sex scenes using the old bed trick, yet the Queen is not self-identical, and so she may be her own doppelgäng-banger. Gospel subverted into gossip, Glenum dishes up bedazzling balderdash where new meanings can forever be gleaned, incommensurating egg word-salad whose nooks and “cavities” are — in all their gloriously bad taste — salty, poetic caviar.

14

This is not to say that Gaga doesn’t sometimes go awry. The portmanteau words, which at first titillate, can begin to sag and seem mechanical. Ditto, the metaphor of sex as a meat-grinder: once the blood sausage has been let out of its casing, we’re less apt to squirm and squeal at the next gonzo gross-out session, and Glenum must resort to the shock of repetition. The overtures to high theory mostly don’t intrude on the poems’ snappy lo-jinks, freighted with their fright wig of pop culture references; occasionally, however, some readers might be more appalled at how theory has been swallowed whole and spit back up at ’em almost undigested. For example, “In making simulacra, we do not displace the real, we manufacture it,” is probably cribbed straight from Baudrillard. Nth wave feminists and grubby grads school cognoscenti, whom I suspect are the book’s target audience, will most likely delight in the frisson of this mixed and mangled fanspeak, as much enthralled to postmodern theory as to music videos.

15

Glenum’s strategy depends on our complicit rubber-necking in which we cannot pry our eyes away from the train-wreck of language mash she creates, her masque of grizzled fleshpots and potty-mouth runts guzzling their own oozy, Uzi-riddled rut. With such lines as “All that grotty jiz crusting to sugar in my ass crevice,” we are given an image at once too saccharine, almost flowery, yet smacking of too much macabre muck. This unlikely combination cancels out the rotten and the overwrought, so that we can revel in the adulterated excess of both. By staging a regurgitation of classical myths, it trades on the fact that seduction can depend on our wanting to be disgusted, disgusting, and déclassé. Glenum’s strategy embodies what Derrida says is vomit’s power to “force us to enjoy — in spite of ourselves,” which nevertheless thereby “annuls itself.” We are finally gagged and balled, maxed-out into a surfeit of pleasure, an overflow that returns to the unspeakable and unrepresentable hole at our hardened core.

16

Language cannot close its own gaps, and disgust embraces desire where language’s embodiments have been left to gape. Rather than being merely comic or horrifying, however, Glenum’s burlesque deconstructs our need for a laminated skin, stripping the poet-performer of her hygienic wrappings, to reveal that the skin itself is already a destabilized drag-show pulling on the body in several directions at once. As Daniel Harris states, “Cuteness. . . is closely linked to the grotesque, the malformed.” The cute and hygienic are themselves distortions, corseted straightjackets that force messy bodies into media-driven plasticine phantasms, enlarging eyes or foreshortening limbs, just as the classical body itself is a fragmented sphinx in the Procrustean bed of the collective imagination leading to the truly grotesque: leaky boob implants, botched Botox, and lurid lipo-suctioned frames. Finally, we may ask, how bizzaro is Gaga, and how much does its technique throw (-up) the pornography of the marketplace back in our face?

17

Glenum’s Gaga demonstrates how shame is a constitutive part of desire, allowing the possibilities of perpetual covering and uncovering — helping us to recover shame itself so that it can be transformed into something (fe)malleable and sexy, allowing its reader to keep poking around to discover new nodes of meaning in the fluid maze of its text.

Will Cordeiro

Will Cordeiro is a poet, playwright, and critic. Currently, he is Ph.D. candidate in English at Cornell.