| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tina Giannoukos and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-gardner-rb-giannoukos.shtml

Angela Gardner

Views of the Hudson — A New York Book of Psalms

reviewed by

Tina Giannoukos

Shearsman Books 2009 ISBN 978–1-84861–080-4 Paper 80pp

1

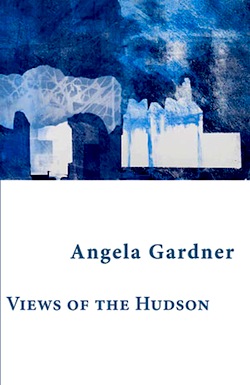

Angela Gardner’s Views of the Hudson explores being a visitor in New York in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Gardner is also a visual artist. The collection’s painterly title reflects this, as does the image in blues and whites that graces the cover. Moreover, the visual acuity and even linguistic precision of the poems reflect this. The title suggests a multiple rather than a single or even panoramic view. The image, which comes from Gardner’s nine-panel monoprint, Vertical Coast, suggests the view of a city from a boat or, perhaps, its reflection in water. Subtitled A New York Book of Psalms, the collection invokes the sacred, putting into circulation the origins of the Americas in utopian imaginings and, in particular, New York’s status as the city of many hopes. In literature accompanying the release of the book, Gardner writes that before she began Views of the Hudson she had been reflecting on “the intoxication and dangers of believing in Promised Lands”. What she wished “to recreate in poetry was the flood of images that results from living in an overcrowded information-rich city”.

2

These sixty sonnets indeed register the poet’s experience of a city flickering and reverberating without end, the opening sonnet alerting us to the agitated narrative of this sonnet series. Marking the start of her New York trip, the poet is on a plane, and an “an announcement warns/take care/contents may shift during flight” (1), foreshadowing the dizzying shifts of observations and intensities ahead. Like the poet, we “stand in awe/the sheer volume of it sheer” (5). Soon the poet is registering the nervous experience of this “unstoppable city” (11) that “trails grey sky from freeways” (12), refiguring the city’s utopian guarantee, where “under this sky here is perfection” (3), as a “cheap arcadia” (6) so that

3

… clear and daylit

and tipped into a promised land

of refrigerators, aircon, long wheelbase cars

A pile em high sell em cheap arcadia

hardly incremental of utopian amendments

This is what I dreamed of

Spanish American & Mexican food served

it was what we were looking for yes?

Our rightful inheritance of home … of home

the lie of the land (flattened and regularised)

Even in the eye of the beholder

everything to hand and something

for others to envy

(6)

4

Gardner does not draw back from the exhilaration that accompanies the longed-for arrival in the Promised Land. She writes:

5

this is the place and everyone knows it

and I am here (do you detect triumphalism?)

Almost unfurled — center the city here

here where I stand and the city doesn’t stop!

(12)

6

Charting her experience in New York, the poet asks:

7

Over a week here now

and where is there redundant light

or movement?

(13)

8

Aware, however, of the city’s endless repetitions the poet rejoinders immediately:

9

A man plays music on a street corner

and we move past something priceless

or its facsimile

(13)

10

Moreover, she refigures utopia as irony, as in sonnet 51:

11

It may be just a distortion of hope

but I see moonlight

on the promised land

12

Nevertheless, this city still holds out a utopian promise so that

13

Everything coexists here

if you can cope this is the place to be

millions know this

(35)

14

The poet, however, often figures her relationship to the city not only in terms of utopia/dystopia but also in terms of the sacred and the profane: “in the valley of salt/where I am high as a kite one minute/and lost the next” (8). Thus, she takes her “place surging with the crowd” even if “the trees may just be monochrome/ink stained after a spectacular Fall”. The word “Fall” here is both a season and a sentiment.

15

The poet’s invocation of the holy, the pleasure of the language, can seem like an urban homage to the degraded sacred. However, the homage turns back on itself, making for marvellously calibrated observations:

16

this is where it is all happening

hedge funds, share options, arbitrage

the accumulation

and dissipation of inheritance

the wash of its tide in and out

Ordinary men that we crowd against

fat and rumpled and harried like us

Say money is the god of us all

whether you have it or not

acknowledge it

the king of all the earth

(25)

17

Indeed, the poet warns:

18

Beware those around you

they have dirty hands and a slippage of values

Words in my mouth coincide with rituals

with paranoia

(38)

19

On the other hand, “the unlikeliest encounters redefine us/make being unexpectedly holy”. Thus, the improbable encounters bring forth the sacred in all its transformative pledge. In the implausible encounter of the city, we discover the spiritual experience. The poet says, “Sometimes I am fearless in this city!” (18)

20

What is the subject of this sonnet sequence? Is it the absence of the beloved, an emptiness, or loss, like many sonnet sequences? This begs another question. Who is the beloved in this sonnet sequence? Is it the city or some absent figure that the poet seeks in the body of the city? It is this and many other things. It is the loss of the sacred. It is also the failure of utopian dreams. In their shifts of insight and perspective the sonnets enact a multifaceted analysis where absence, loss or, indeed, emptiness, are figured and refigured each time so that

21

With him at my side

there is a strange elasticity to reality

each object in heightened conversation

with emptiness

(8)

22

Nevertheless, the sequence activate the sonnet’s long engagement with the figure of the beloved, so that sonnet 7, for example, plays with the erotics of two bodies in juxtaposition:

23

two figures caught in a lighted wall

searching the fine tonality of skin

we struggle with nakedness

from cleavage to cunt

24

However, with a contemporary twist on the erotic, sonnet 30 asks:

25

and after all where else would I go for abuse

without you?

26

In a Nota Bene, Gardner declares that these sonnets, with their uneven line count, are nevertheless sonnets in that she counts them as possessing fourteen lines, that is, she counts the gaps as lines also. Leafing through the book, one perceives sonnets, even when the line count appears short or the lines themselves are truncated. In other words, in their semblance of regularity, the gaps functioning to put back what is missing, that is, the line itself, these poems look like sonnets. They read and sound like sonnets. The poems possess a sonnet’s philosophical mood.

27

The Nota Bene, however, invites a discussion. This discussion is less about the poems themselves, their success, and more about a gap as a line. If it can function as a line, then what is the effect of a gap as a line beyond appearance? Why even note the gap or even circumscribe its meaning? The difficulty is that if the poet makes no note about it the reader, much less the hearer, of these sonnets may not tease out the sonnets in the way the poet intends, perceiving the gap as merely that. The problem, however, is how to register the gap as a line and not simply a play in visual space. Still, poets have been making silence visible in their poems and not simply referring to it for a very long time.

28

The poet e.e. Cummings, himself a maker of exquisite lyrics and a painter, not only refers to silence in his poems, as does Gardner, but like Gardner makes that silence visible to the eye by such visual devices as blank spaces between words. In the lyric, these visible silences, gaps, and absences that also colour Gardner’s own poems take on an added aura. Gardner repeats her silences throughout so that on the flight over “screens flutter mutely” (1). On her arrival “in the crowded terminal at JFK” (3), the poet says “I can hear the uncomfortable silence/in all this noise” (3) where “a voice divides space/days surrounded by strangers” (9).

29

Not all the sonnets, of course, possess gaps as lines. Some possess 14 linguistic lines, the effect of which is to underscore this lyrical sequence as a sonnet series against which the gap as line begins to work in those poems that do posses gaps so that

30

(she leans over his bent back

composed

like a stem of an always-Mapplethorpe lily)

what is hidden?

(55)

31

Gardner’s statement on poetics counter-intuitively positions the sonnet, a closed form, within that body of work that foregrounds visual space, making a distinct visual prosody a part of these sonnets’ formal arrangement. In this, Gardner partakes in an experimental approach to the sonnet throughout the twentieth century in which we sometimes barely identify the sonnet. In positing the gap as a line, Gardner interrogates even a sonnet’s safe docking in its harbour of 14 lines, where each line consists of words, not gaps. She does not thereby abandon aurality in favour of the visual, even if the problem of how to articulate the line as a gap remains.

32

Perhaps a long pause is required, though from poem to poem the duration of the pause may differ. She controls, however, her sonic and rhythmic effects as much as the placing of her gaps. She plays long lines off against shorter lines. She also plays off the 10-syllable iambic pentameter line against other prosodies. What is precisely startling, however, about these sonnets is the way the visual does play off the aural, the gap often pulling us up so that:

33

and if I find it

… it will be at the point

where the mirror or blurred window

or the book I carry

are where I would be

downtown

between marble entrance foyer and something tinsel

a doorman building at Christmas maybe

If a book

then bookshelves are pulled from the rubble

and missing pages prevent cave-ins

some days I dig a pit

to fall straight in!

(15)

34

Nevertheless, a question remains. The regular appearance of the sonnets, the gaps usually making for 14 lines, gives the illusion of a traditional sonnet, which the gaps as lines subvert. Where we expect a line, we see only a gap that, however, we may not necessarily perceive as a line. These phantom lines intensify those silences and absences that haunt these poems. The accretion of the gaps as lines from poem to poem enacts their effect. In their presence from sonnet to sonnet, their varying appearance within the sonnets themselves, now a gap here, now a gap there, these gaps that count as lines are suggestive of the absences that haunt this city, even mark its vulnerability. It makes present the absence brought about by destruction or the fear of its threat. The gaps gesture towards and even make present that absence that marks New York itself: the destruction of the World Trade Center Towers.

35

Take sonnet 50, which has 15 lines, if one counts all the gaps, the cumulative effect of which is to intensify the silences and absences of the poem, especially its vulnerability:

36

it is a different kind of emptiness

to trust in background

tea stained wallpaper

the colour of leaves in the Fall

Adults make crayon drawings

yellow ties

and a little dog looks for warmth

I used to comfort myself

that the news gets out by cell phone

but the truth is

politicians still stand at podiums surrounded by flags

and the strong city may be destroyed

37

However, Gardner also deals in presence — in what is there. However, here, too, the gap works against the materiality of the city, activating the numinous or sacred instead or, rather, its loss:

38

But mark well the towering architecture

the elevators and escalators of Macy’s

And as you walk the streets

consider the question of scale

the harmonious regularity of the grid

God is our God

(12)

39

Moreover, hers is a nuanced response to the silences or absences that haunt a city so that the poet says:

40

… I trust in silence

as we walk under trees

Bryant Park unter den Linden

on crushed gravel paths (so very European

a place where cities have already

been made and destroyed

or just buried under indifference)

(19)

41

Gardner is, however, aware of the effect of the city and New York in particular as architectural display which she once more ties to the sacred :

42

Some buildings tower over our lives

become our architecture of existence

the days remain unquiet

with the inequality of money

narrow passageways of loss or opportunity

Subdued in this metal box

a daily commute ends

an overwhelming vertical ascent

not contemplative and slow

but fearful and enclosed

and with all the city below my feet

I am at my closest to prayer

(29)

43

The effect is to bring back into focus the materiality of the city, which she simultaneously undoes in her use of gaps and ellipsis so that everything is under constant interrogation:

44

The city is being documented by amateur

photographers — open lens intent

the workers untied will never be defeated

and we shall find a new refuge

for the oppressed…

(19)

45

Often, this interrogation has a heightened tone:

46

I want to believe it makes a difference

our crowding together like this

pooling our burden of neurological disaster

into the other side of a dream

as if a voice will say …

Quiet… quiet on set

(26)

47

It is always interesting when the visual and the poetic combine in the body of the poet, for it produces a heightened awareness of the body moving through space. In this respect, Gardner is interesting in both her images and her language. Her acute visual perception combines with an equally acute linguistic facility to produce unexpected visual and linguistic relationships that capture the angles and planes of a city. In doing so she recuperates the sonnet for a more fractured, urban sensibility so that

48

clouds reach towards the sun

in a spectacular act of perspective

hiding within my own shadow

(18)

49

The emphasis is often also less on the bearing down of the image, the angle or perspective, and more on the progression, the swift view, the movement itself into the observation of the city and of its myriad, complicated happenings:

50

My own grimed reflection

shades of mortality rubbed and dissolved

to a hieroglyphic snail of meaning

over and over

over and over

in each storefront window

(14)

51

The emphasis is also more on the transience of the detail, the eye and object in quick relationship, the agitated response, the occurrence and intensity of the thought, the overflow even of an image. More often than not, the poet is communicating the process of an event’s happening-in-the-now. Some of Gardner’s images, which often register ephemeral observations or transient urban visions, catch the image in the process of change :

52

The surface of the moon

smooth where it has touched the briny water

dips into the ocean

and is changed by the actions of the waves

(51)

53

Her careful images played off against her precise language produce immensely complex sonnets whose surplus of meaning threatens to overwhelm the poems, as if the overflow of thought and sensation might split open the sonnets that yet resist this levering. Despite their surface clarity, they can appear opaque:

54

Walking under epileptic street signs

neon in daylight

beauty and stupidity

I forget celebrity is always mass produced

and still looks like cheap plastic toys

we crowd around insistent expectant

needlessly amazed

At night I slip and fall darkness under me

No! it can’t be, like this

I continue to do as I should

… so why won’t it work anymore?

(24)

55

Often the poet is registering the process of an already receding happening, perhaps her response to the particular but by now receding episode, which produces all sorts of nervous agitations:

56

Now the cold has set in

I judge myself hardly

a forgotten face in the crowd

Hardly a forgotten face

in the crowd

My hand previously marvellous

refuses to obey

while my heart is removed

and left tilted

— it is a bird on a chain

looking down on the city

I cannot fly — hold me

(37)

57

Ultimately, her use of the visual translates into a heterogeneous registration of multiple, ever-shifting perspectives, colours and angularities. Sonnet 11, for example invokes in part the colour of urban streets at its prosaic, yet lyrical display:

58

The sidewalks are full of tulips to admire

to buy. Tulips bowed under the weight

of their colour

burnt orange, cadmium red, Bordeaux

a broken line along parrot lips

& tongue

59

On the other hand, sonnet 31 addresses the question of seeing so that:

60

Don’t look down into a day

that has no understanding

of what is won or lost

Terrified by the height (32nd floor)

distorted flat to optical illusion

61

What we repeatedly notice throughout the collection is Gardner’s careful use of language. She displays no verbosity. She places her words precisely. Moreover, words speak to each other across poems, recurring in unexpected places or ending one poem and beginning another. For example, the word “emptiness ends one poem — “emptiness is just emptiness” (38) — and almost bar one word begins another, its abstraction concretised in the subsequent lines:

62

But emptiness as idea:

remember the double feature?

Afternoon’s celluloid escape

into the safe suspended warmth of belief?

(39)

63

This facility with language allows her to push its figural possibilities. Moreover, it participates in that agitation that colours these sonnets so that:

64

here in this crowded space

dripped paint on polished concrete

an old-fashioned sink and stuff on the floor

stuff

Over us a narcotic flinch of music

that makes me anxious

(26)

65

In conclusion, these sonnets make for an intellectually provocative collection, the virtuoso play of images and language superbly executed, and the shifting perspectives offering potentialities of visions and ideas.

Tina Giannoukos

Tina Giannoukos is a poet and fiction writer. Her first collection of poetry In a Bigger City is published by Fives Islands Press. She is completing a PhD at the University of Melbourne. Her poems have been published widely, including Blue Dog and Blast.