| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 6 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Thomas Fink and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-duhamel-rb-fink.shtml

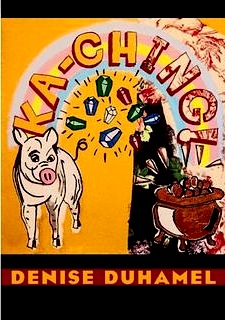

Denise Duhamel

Ka-Ching!

reviewed by

Thomas Fink

86 pp. University of Pittsburgh Press. Paper. US 14.95. 9780822960218

1

In her nine previous books, Denise Duhamel has always lavished her poetry with the immediacy, relevance, incongruity, and humor of sociopolitical circumstances and eruptions. Happily, Ka-Ching!

is no exception, and it also intensifies a trend in Duhamel’s work of this decade, beginning with the new poems in Queen for a Day: Selected and New Poems (2001) to include formal experimentation with social representation/analysis, often alongside reasonably straightforward narrative poetry. Not only do her seven Elizabethan “e-Bay Sonnets” feature a good number of Dickinsonian slant rhymes and shifting word-endings, but “Delta Flight 659,” a jaunty homage to actor Sean Penn, plays off the sestina by ending each line with a word include “pen,” ranging from “pentameter” and “expenditure” to “penguins” and “penitentiary.” Pete and Repeat are characters in a modified pantoum about childhood experience, and there are two intricately anagrammatically driven poems; “The DaVinci Poke” is a parody of Dan Brown’s best seller with a pornographic twist, and “Anagram America” teases out various pleasant and ominous significations regarding notions of American democracy:

2

I’m an undercover agent, ma’am. I care

about civil liberties, though, and still believe in the ACLU — a crime, a

naïve throwback, I’m told. America tends to maim, care-

ful not to kill at first. We’re all for democracy or so we claim, care-

less with our rhetoric. The Korean became Vietnamese became Ira-

qi…

Welcome to America

where the letters can be twisted into almost anything, even Ma, I care.(78)

3

Of course, Duhamel is well aware that this use of the proper noun “America” is an example of careless “rhetoric,” a dubious synecdoche for the United States of America — automatically used by politicians of all stripes — but her resourceful use of its letters allows the poet to arrive at some of the paradoxes of “careful” and “careless” national behavior throughout U.S. history. On the one hand, there is considerable care to preserve aspects of “democracy” within local, state, and national government and in dealings with foreign allies and to “claim” close to a total (or at least unprecedented) realization of democracy. The cliché of “mom, god, and apple pie” evoked in the last anagram of the poem involves a belief in the fundamental good-heartedness of “Americans,” but such a focus excludes selfish and sometimes brutally undemocratic acts by the government and large corporations catalogued by such revisionist historians as Howard Zinn.

Denise Duhamel

4

Further, during the Bush administration, “the ACLU” is called “naïve” in opposing extreme provisions of the Patriot Act, and in the pursuit of global adventures, the U.S. government has proven indifferent to distinctions between “non-white” countries and ethnic groups. What in the first Gulf War was called “collateral damage” is one aspect of the maiming to which the poet alludes, and a potent example of the U.S. lack of accountability for inadvertent “maiming” can be found in “Sipping Café con Leche Where the Bombs Fell,” a poem of political tourism in this volume.

5

“Weapons Inspectors’ Checklist” entails an alternation of lines from Duhamel’s original poem and ones following a translation chain (by others) including Ilocano, Tagalog, Spanish, Italian, French, German, and finally returning to English. Though in some cases there is no difference between the original and the translation, the poet uses this game of “telephone” to demonstrate the potential political dangers and absurdities of mistranslation:

6

Do they pump their own gas?

Is the gas in this forsaken land rationed? (79)

Do they sell anthrax to terrorists?

Is it possible that they sell anthrax to terrorists?

Do they have a T.J. Maxx?

Do they know a man called T.J. Maxx? (80)

Do they have soldiers disguised as children?

Do soldiers like to dress up as children?

Are their children products of their environment?

Where do all these products manufactured for children come from?

Do their children hate going to school as much as ours?

Would they like their children to be raised as well as ours are? (81)

7

The poem was written in August 2002, as the limitations of the early Bush administration’s foreign policy were becoming glaringly apparent. The opening question in the passage above seems irrelevant at first, unless the usual use of “pump” is ignored, and we decide that the verb signifies the importance of oil production in the U.S. government’s decision to concentrate on Iraq. In the translation, however, the pejorative term “god-forsaken” somehow pops up, and the notion of rationing ironically suggests that this oil-rich country is filled with impoverished people. Various questions focus on cultural trivialities like the retail chain T.J. Maxx, as though gauging the impact of American cultural hegemony rather than finding out whether Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had produced “weapons of mass destruction.” Further, arbitrary losses of context turn reasonably respectful and sometimes valid questions into impertinent or ridiculous ones. The pseudo-philosophical question about nature vs. nurture is turned into an issue of capitalist production, and the awkward attempt to strike a common ground between U.S. and Iraqi children is transformed into an insult against Iraqi parenting.

8

Perhaps the most jolting formal achievement in Ka-Ching! can be found in “The Language Police,” title of a book by Diane Ravitch denouncing “political correctness” as fascistic in this area. While Duhamel has exposed the harmful impact of denigrating signifiers on women and others throughout her career, she demonstrates that even a good form of protection can become stultifying when taken to an extreme by those who ignore how language works. Constant parenthetical interruptions in her poem threaten to destroy a reader’s attempt to follow the argument in this five-paragraph text:

9

The busybody (banned as sexist, demeaning to older women) who lives next door called my daughter a tomboy (banned as sexist) when she climbed the jungle (banned: replace with “rain forest”) gym (alternative: replace “jungle gym” with “play structure”). Then she had the nerve to call her an egghead and a bookworm (both banned as offensive: replace with “intellectual”) because she read fairy (banned because it suggests homosexuality; replace with “elf”) tales. (25)

10

The critique of “tomboy” is legitimate. However, even if the disagreeable neighbor is an old woman, who decided that “busybodies” are seniors or women? And are intellectuals so sensitive that they can’t take a little clichéd ribbing? Granted that “jungle” is sometimes use to disrespect African and Africans, the word has a neutral use; since “rainforest gym” is laughable, the lingo police adopt a term so lifeless that it leaves out the spirit of play. Also, it is easy to distinguish between a fictional being labeled “fairy” for many centuries and homophobic denigration, and nothing would stop gay bashers from switching over to “elf.” When “fanatic” and “extremist” are labeled “ethnocentric” — as though political or religious fundamentalist do not come from various races and ethnic groups — it is indicated (fascistically) that one cannot make a strong judgment about others’ beliefs but can only use nouns (such as “believer” or “follower” that convey neutral descriptions. At once, the last paragraph asserts and disrupts the speaker’s thesis:

11

As an heiress (banned as sexist: replace with “heir”) to the First Amendment, I feel that only a heretic (use with caution when comparing religions) would try to stop American vernacular from flourishing in all its inspirational (banned as patronizing when referring to a person with disabilities) splendor. (25)

12

To make the gender distinctions Mr./Mrs./Miss is sexist because there is a double standard, as is poet/poetess or sculptor/sculptress, which implies inequality in fields long governed by patriarchal stipulations, but “heir/heiress” is not in either category. “Inspirational,” though, is proscribed because one context of many (and not the one intended here) is “patronizing.” Most of Duhamel’s examples of banning undermine themselves and thus allow the syntactically and visually fractured thesis to glue itself back together.

13

The section “Play Money” consists primarily of single-paragraph prose-poems published sideways to allow for very long lines and to resemble bills. The first poem is entitled “ 100,000 and the last “ 1,000,000,” and the texts are objectified, like money, because of their grey fields and dark, shadowy frames. Indeed, since “play money” is a transitional object designed, I suppose, to enable kids to enter and accept the symbolic realm of monetary exchange, including a stimulation of their potential for acquisitiveness and anxiety about class positioning, Duhamel repeatedly brings these issues to the fore:

“As a kid I loved being the banker in Monopoly, in the Game of Life — the pink and yellow bills not quite as big as our U.S. currency, but closer to food stamps. The board games had no coins, snubbing the paltry dimes of hobos and kids” (3). What easier way for a working class girl from Woonsocket, Rhode Island to enter the fantasy land of privilege, though she simultaneously registers Monopoly moolah’s resemblance to food stamps.

14

Outside this game, she is involved in another with the smallest actual change, and this, too, influences her socialization: “I had a penny collection, round slots in a blue cardboard folder, and I’d search for dates while rummaging through my parents’ change, hunting for pennies that became worth more than pennies, the value of what is rare. The 1943 copper alloy penny, the 1955 penny with the year stamped twice, the 1924 penny with the letter “S” after the date. I loved rolling coins in wrappers, my favorite being the quarters with their hefty ten-dollar payoff…”

15

The narratives (and sometimes multiple, braided narratives) of these prose-poems go beyond play money, pennies, and childhood experience in general to show how the symbolic structures of monetary relations can insidiously infect adults’ daily lives. There are lessons about women’s linking of body weight and financial heft, the dubious merits of hoarding, the economics of urban apartment dwelling and the bizarre side of ATMs, and evidence about disparities in luck due to the randomness of clusters of individual circumstances: “But who doesn’t have fears? Who doesn’t try to prepare for the worst?… So much can go wrong, even when you believe in nest eggs” (10).

16

At various points in this section, Duhamel seems to allude to the possibility of a political analysis of these disparities. In the United States, right wing and sometimes centrist resistance to “socialist” moves like universal health care coverage reminds me how many ignore the notion that individual “fate” is so unpredictable because the capitalist marketplace’s flux is not sufficiently balanced by government “nest eggs” for its citizens. And while the section, “one-armed bandits” — a group of poems about Duhamel’s parents’ near fatal falls on a suddenly dysfunctional Atlantic City casino escalator — focuses more on the intense dislocations and deprivations of this event, there is also the implication that sizeable corporations with access to first-rate legal manipulators can shrug off responsibility for the damage they inflict, and thus, working class people try hard to manifest the effects of their suffering but cannot turn their misfortune into the “good luck” of substantial reparation:

17

But the casino won’t pay out since they are going bankrupt, changing their name. The escalator company says the casino is at fault since they didn’t properly maintain it… The slot machines keep whirring. Bars, dollar signs, the number 7…

My parents’ case never goes to trial. When they get their settlement, they throw away their bloody clothes and shred a prospectus for a preconstruction seaside condo. My sister takes the pictures of my mother, her injuries, out of the safe and burns them in the fireplace. (66, 67)

18

Poems about egregious exploitation like “Stupid Vanilla” and personal trauma dumped on others like “Apple” also spotlight the individual dimensions of “bad luck” but imply the absence of social safety nets and the often complex impact of inequalities. (Late patriarchal ideology, for example, is roasted handsomely in such poems as “’Please Don’t Sit Like a Frog, Sit Like a Queen,’” “Cinderella’s Ghost Slipper,” and “Spoon.”) An interesting twist in “Stupid Vanilla” is that the harshly exploited and disrespected au pair is a less than privileged white college student and the parents are upper crust African-American lawyers.

19

If much of Ka Ching! (with its title’s gambling onomatopoeia) refers to good and bad luck, Duhamel is not demonstrating that luck does not exist, since all events are traceable to sociopolitical circumstances, nor does she suggest that “Fate” rules. For her, social conditions and trends have a great deal of influence, yet sometimes complex poetic narratives resist thoroughly ideological explanations. For example, that Americans like Duhamel’s parents would be manipulated by structures like “Monopoly” to visit the casino — a trope of finessed chance (“luck”) — and, after the accident, would be cheated by corporate hegemony of a decent settlement seems highly likely. But can one necessarily assume that greed and carelessness on the part of the escalator company and/or the casino regarding maintenance caused the horrible malfunction, especially since such events are extremely rare?

20

And, of course, any casino-goer of a variety of class and other backgrounds could have been on the escalator at that moment, and such escalators could just as easily malfunction in buildings that do not particularly stimulate acquisitiveness, so the Duhamels’ bad luck cannot be entirely placed in a political frame. The poet does not call attention to this in this poem and others in the book to depoliticize anything; she shows respect for the political by pointing to areas where it may not apply, where explanation in general falls short.

Thomas Fink

Thomas Finkis the author of A Different Sense of Power: Problems of Community in Late-Twentieth-Century U.S. Poetry (Fairleigh Dickinson UP) and co-editor of a recent collection of essays on David Shapiro. Marsh Hawk Press published his fifth book of poetry, Clarity and Other Poems, in 2008. His work has appeared in Best American Poetry 2007 (Scribner’s). Fink’s paintings hang in various collections.