| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 7 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tony Baker and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-duggan-rb-baker.shtml

Laurie Duggan

Crab & Winkle

reviewed by

Tony Baker

Shearsman, 2009, 164pp, paper, isbn, £10.95 / 18.50 ISBN 9781848610491

Laurie Duggan

1

On the 3rd of May 1830, as the first train on the Canterbury-Whitstable line entered the narrow, half-mile long tunnel that had been forced through Tyler Hill two miles short of its destination, it was hauling a number of particularly compact carriages from which a hand reaching out would have scraped the tunnel walls. The passengers were the mayor of Canterbury, together with a number of aldermen and local dignitaries. Further trains were reserved for their lady consorts and a fanfare that played, as it had since the train’s departure, celebrating the completion of a feat that had brought together three of the most renowned British engineers of the epoch: Stephenson, Telford and Brunel. How the acoustic character of that confined space transformed the voices and instruments and mechanical clankings as the carriages slid towards the darkness of the hill’s interior, was said to be “novel and striking” by a writer in the local newspaper. The increasing sense of suffocation must however have added anxiety to the tone of the clamour “echoing through the [tunnel’s] vault”, notably in the third carriage, for at least one passenger — who later walked home — began to feel she might never get out alive.

2

The space in which it resounds alters the nature of any noise; indeed it gives it its nature. Gavin Bryars once composed a work that derived initially from trying to imagine what might have happened to the sounds made by the Titanic’s band as they famously played on even as the upended ship sank below the ocean’s surface. This was no simple metaphor: the work is a contemplation of how the actual sounds emanating from the vessel might have been altered as it plunged beneath the waves. According to Bryars’ notes, Marconi, whose telegraph was first used in a maritime rescue when the Titanic was lost, believed at the end of his life that no sound finally vanishes; it’s merely attenuated to the point of imperceptibility. In which case a sufficiently sensitive antenna might in theory pick up the residual resonances from any acoustic event; and history would be audible in the air we breathe in the same way that, at a cosmic level and given the right instruments, astronomers consider it visible. Such an infinitely refined and eternally modified fuzz of babble would presumably include echoes from the voices on that May day in the tunnel in Kent, though the local modification that turned “Canterbury to Whitstable” into “Crab and Winkle” was no doubt invented at a later date when the line took holiday-makers to Whitstable’s port, renowned for its seafood, and became the world’s first railway to issue season tickets.

3

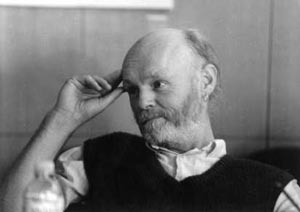

The Crab and Winkle Way is now — half a century after the railway’s closure, quarter of a century after its tunnel’s partial collapse, and several decades after it became a piece of transport history lost to vegetation and private landowners — an 8 mile cycle track and the name on a specially brewed beer only available in a handful of Whitstable pubs. It would be a happy contrivance if the half-downed pint that Laurie Duggan holds in the author photo for Crab & Winkle is named as his book but, like the evidence presented in much of the writing itself, we believe what we can. He writes as a stenographer of the immediate, not as its theorist. There are pubs and pints and the hum of voices — heard, misheard, reheard — throughout his book and they supply the sound zero on which it’s constructed. As if emerging from the Snug next door, the foundations of the work are a sort of Marconi-residue of wordings to which Duggan himself is the antenna. Some of the wordings are too faint even for his ears

4

When the [ ] sings before dawn

from the branches of the [ ]

the blue [ ]s unfurl

while grey [ ]s encircle the skies,

5

an ‘Immigrant Spring Poem’ in which the loudly singing cuckoos and blowing cows of history may/may not be heard in the parenthetic silences; and some of these wordings hammer the immediate air so noisily that they soar into the red zone where language distorts into a blitz of instant polyglot impulses

6

Guerre froide. EGGS UND HOPP. MILLIONS OF DEAD COPS. Axel und Christian waren hier 14.10.82. The WALL must broke. PUNK DUNK UBER ALLED I LOVE IT. FUCK THE SYSTEM. BREAK DOWN THE WALL. FUCK THE WALL.

7

The book in fact is an ensemble of instances — the sort of thing that might have been recorded had a microphone, set in the tunnel-wall as the world’s first passenger train passed, been left to capture the scraps of conversation, thought, wonderment, rhetoric, fascination or panic as they entered and left the audible field. Except that Duggan’s train runs in the tunnel of history (particularly literary history) and his microphone is specially prone to pick up contemporary noise (particularly that made by poets and painters and people hanging around in pubs).

8

One gets an idea of the texture of the work from the acknowledgements that precede it: “This long poem contains many quotations, some identified, some not. Some are from anonymous sources, various technical instructions, Berlin wall graffiti, the Faversham History website, advertisements, legal documents, newspaper and radio items, the voices of various pub inhabitants and an audio recording of myself aged five. Others are from specific individuals, some long dead, some very much alive, some fictional.” Which is to say the author is a sort of tracking station for day to day detail which, over the course of a year he has noted down, alert both to the background hiss and the foreground evidence of what comes worded to his ears. It’s set down like diary entries in a calendar of nearly indiscriminate events that Duggan himself has likened to the procedures of a traditional Shepherd’s Calendar whose design he feels emphasises “continuity”, though he admits that it’s “an arbitrary structure for something which is pretty loose”. The parallel could be pursued in other ways. If we follow Spenser’s own introduction to perhaps the most well-known of the Shepherd’s Calendars in English literature, Duggan’s work contains “extraordinary discourses of unnecessarie matter” which suggest we enjoy what Sir Edmund wonderfully disdains, lobbing contempt in the face of the “rakehellye route of our ragged rhymers” who have made of the English language “a gallimaufray or hodgepodge of al other speeches”. Exactly in fact what makes Duggan’s work entertaining.

9

It’s difficult perhaps to suggest that writing — and this is poetry for heaven’s sake — might be entertaining without simultaneously hinting that it risks superficiality, as if it were merely amusing and its function were to distract attention from what would otherwise be the vacuity of leisure. I recently had a short correspondence with a poet, himself driven to distraction by a particular kind of poetic discourse so remote not just from the notion of entertainment but even from the very idea that it might invite the reader in, that it seemed to him actively to spurn the reader, preferring to wrap itself in a procedural self-consciousness that turns its back on what the world might offer as common ground. That a writer should be in some sense host to his or her readers and might feel some social inclination to entertain them — as the mind entertains ideas — is, in this context, an alien notion. Duggan is clearly aware of what’s at stake. This is his commentary on an art show in Newcastle’s Baltic gallery: “the problem of art that is fundamentally conceptual but that insists on illustrating itself (the practice often painstaking and literal)”. Much poetry in English — Chaucer? Elizabethan theatre? Kenneth Koch? — would lose its energy if it was reluctant to entertain, not least because in contexts where it’s going to be heard but not necessarily read (even supposing its audience is capable of reading) it has to do something to engage the attention. In spite of the wealth of performance practices and publishing methods explored by poets in recent decades, the silences of the page still weigh heavily on both the reading and the making of poetry, reinforcing the sense of it as an essentially solitary sort of research that’s lost touch with its communal and ritual roots. The page is an asocial milieu. Why should it bother to sing to us as if it were a troubadour?

10

There’s an irony here since Duggan’s method in Crab & Winkle is a form of solitary research — a patchwork diary of idiosyncratic concerns that are quite happy not to force connections and readily set down allusions that are arcane or likely to be out of the reader’s reach. If you read

11

little contingencies

for whose delight?

not the brashly confident young barman?

12

you might recognise a form of self-interrogation, for the book is full of little contingencies and the writer might well ask himself just who they can matter to. “For whose delight” suggests that the reader’s enjoyment matters to Duggan even if he may be laconic about it. But the italics on the phrase would remain unclear unless you happen to know that this is the title of one of the late Gael Turnbull’s pamphlets, a poet mentioned elsewhere by Duggan and one who was specifically concerned towards the end of his life to entertain others. Turnbull took to making word-objects, constructions, games, machineries — devices that he glued and nailed together himself from materials recuperated in skips or bought from DIY shops. He placed his words in situations where they appeared on street-corners and went seeking their audience. Pushing his home-maderies around in a wheelbarrow, he busked with them in the streets of Edinburgh, and would have as happily sought the attention of a two year-old as of a ‘brashly confident young barman’. Duggan’s discrete italics place the performance and pertinence of his own contingencies in a wider context; indeed they directly evoke the question of address and engagement with an audience but in a way so abstruse that only someone acquainted with Turnbull’s work might catch it.

13

Impenetrable reference isn’t going to trouble a reader of contemporary poetry. It’s what the poet does with it that matters. In so far as it deliberately (or lazily) occults the poet’s material it serves to distance the reader; but where it’s offered as a contour in the topography of an imagination whose reclusive truths can never fully be known to another it may be as complete an invitation as the writer knows how to make. We take on trust the details of circumstance the poet sets down because we feel that in bothering to communicate them at all the poet’s intent is social. This is the poet as host entertaining his reader with soundings in the Marconi-pool of the world’s noise:

14

myth is a way of explaining, not a strategy,

as the figure is discovered in the ground?

a twitter in the bush beneath the blasted oak

St Hilary’s Day, supposed to be the coldest in the year

parts of Hamburg under water

15

Do these stabs in the dark of forming thought, like one half of an attempted conversation, construct into poetry? Duggan writes the question into his own text: “Remember the critic who suggested that my work was ‘the poetry of lists’ (I don’t think she meant this to be flattering)”. The irony here suggests that Duggan himself might find it flattering whatever the critic’s intention, yet he defends himself against it nonetheless. He admits he has a short attention span (though this might be a self-deprecating way of saying that he’s interested in lots and lots of things) and a poetry of lists that jumps from matter to matter might be the natural mode of his imagination. But his imagination also naturally works with shapes and the exact fit of all that he notes is the sap of both his poetry’s craft and its lyricism. Without these elements the 160 pages of his book might indeed reduce to an alignment of lists; but Duggan is aware of how his ‘mulch’ of detail, if jointed with a craftsman’s skill, becomes something more than that.

16

so, the scattering

of phrases, the mulch

making up this (or

making this up), things

don’t hold until

a strange discourse

takes over, the notes

blind to purpose

except the track

of improbability…

17

And the “strange discourse” is what entertains the reader not least because Duggan’s discursive shapes are innately lyrical. He hears phrases as lyrical forms (he is a scholar of the visual arts and seems to hear the shape of a line as a painter might see it). For him “texts strip down to phrases of music”. A shaped list becomes lyric not because it’s made up of lyrical matter (what would that be anyway?) but because it’s shaped to be lyrical: the matter discovers its lyricism in the way its musical phrases are put together. So the silences in his pages — and there are many, both visual and implicitly musical — are part of a lyric design quite consciously paced. “Time is what it’s all about for me. Time is rhythm and space”, he notes in an interview adding, in an observation worthy of Miles Davis, that “with music in general I’m thinking of space because it’s through the use of space that structures of rhythm come about”. Here time is about timing — about when a phrase is made to occur. As the musician or sports player knows, it sounds sweet if it’s timed right. Poetry’s no different: if it’s badly timed — the right word in the wrong place — it clunks.

18

Duggan’s poetry has the virtue too that it never “abandons the local”. Like Paul Blackburn — a poet Duggan manifestly admires — he builds his work out of what he finds in, on or about the premises. He searches in the immediate, not the mediated. Crab & Winkle is local speech, current only in the particular part of Kent that Duggan’s book explores. Part itinerary, part calendar, part journal, part pub crawl, it’s a loose structure with a tight focus, managed with such sleight of hand that you might easily miss the skill he brings to bear. Here’s the book’s prologue, homing in on the only possible site for its meditations in a luminous sequence of subtly timed words:

19

Through cumulus, the hump of Thanet, then Pegwell Bay.

The University of Kent, Canterbury downhill like a 19th century painting.

Cathedral dominant. A low rise city in the valley of the Stour.

A half-timbered hall: Beverley Farmhouse.

A bed that barely fits its room.

20

From that room Duggan’s antenna sweeps the air for what it holds of the world’s noise. It might have reason to be particularly sensitive to voices from the heart of Tyler Hill for the tunnel provoked subsidence to some of the University of Kent’s buildings in 1974 and its vaults were largely filled in. If the remaining echoes from the voices that encountered the hill’s inner darknesses in 1830 were driven out at that time and condemned to walk the earth, they may now find themselves lodged in Duggan’s book, disguised in the accents of a woman walking a dog, a passing cyclist, or — anachronistically and accidentally — Bessie Smith for example. If the book’s last page asks the question “how much of it ‘adds up’?” you know that Duggan has some of the answer already. It can’t “add up” because it’s essential matter is necessarily all over the place (including history). Readers willing to be entertained though must have a fair chance of encountering bits of it in The George about to have lunch and, for the price of a pint, might find themselves invited to be part of it.

Tony Baker

Tony Baker was born in south London in 1954 on J.S.Bach’s birthday. He studied piano and composition at Trinity College, London, literature at Cambridge University and subsequently completed a PhD on William Carlos Williams at Durham University in 1982. Since then he has worked mainly as a musician and ecologist. He has written a book on the history of mycology and co-authored another on creative work with autistic children. He edited the poetry magazine Figs from 1980–89. With a home still in the Derbyshire Peak District, since 1995 he has lived amongst the vineyards near Angers, France.