| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 25 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Catherine Daly (music) and Crisman Cooley and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-daly-vauxhall-rb-cooley.shtml

1

A reader of contemporary poetry travels in a strange country, or rather many

strange countries, without a lonely planet guide. Once in a while, he finds a

country, no larger perhaps than a pleasure garden, where the inhabitants are

engaging and witty and the weather’s fine. Catherine Daly’s latest

book Vauxhall is that kind and I’m writing this brief travelogue to

share some of my experiences there.

2

On the whole, it appears that the reviewer is at a great disadvantage to the authority of the text, being a mere tourist in it; and maybe that’s why some critics say ill–mannered things and pretend to be the voice of posterity — because they feel vulnerable in a foreign country. In the face of his own ignorance, the best a reviewer can hope for, having admitted that the review will likely be more about himself than about the territory in question, is to bring the sharpness of an outsider’s eye to the scene, and, like de Toqueville, to mention some features of the country that the inhabitants themselves may not have noticed.

3

The frailties of a reviewer can be fortified by treating the text as an object of scientific inquiry. Though I am not a scientist, I can look at a text as a fact — that is, scientifically; and as a fact related to other texts as facts, leaping CP Snow’s cultural divide in a single bound.[1] The leap, as applied to literary criticism, is a result of advances since 1959 in and around the field of semiotics.[2]

4

For our purposes, I’ll be searching for esthetic value on the two planes of language: the expression plane and the content plane.[3] The expression plane is the realm of the signifiers (words on the page or sounds in a recording); and the content plane is the realm of signifieds (concepts — those things signified) for which the sound concepts stand.[4]

5

On the expression plane, the search for esthetic value means looking at rhythm, assonance, internal rhyme, alliteration, phrasing and perhaps other musical effects. Traditional scansion we can expect to be of little use, since we are not dealing with formal verse.[5] Instead, I’ll use more subtle and powerful tools of contemporary music notation to transcribe a recording of “Halloween” from Vauxhall poem “Candy”.

6

On the content plane, I’ll search for esthetic value by looking at the images created in the mind, historical references and quotes, the sensual recall, the philosophical implications, and other mental effects. This essay will only begin to suggest how the analysis might proceed and what literary values will be brought into the range of discovery.

7

As the new methods and nomenclature evolve of this proposed form of analysis, it might become one basis for understanding how poetry that is not formal in the traditional sense can still be lyrical and even beautiful. This could answer critics of contemporary poetics (as a courtesy) who have said that contemporary poetry, outside New Formalism, is unable “to establish a meaningful aesthetic for new poetic narrative”.[6] In this essay, we’ll be searching for the esthetic of the deeper music.

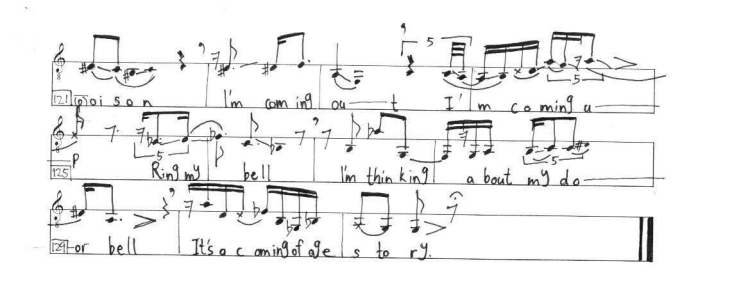

8

In the process of preparing this review, I have had certain communications

with the author and received information about the work that isn’t

available to a reader of the text without these communications. Information

received in this manner will be noted.

9

The following biographies give clues into the life and personality of the poet.

10

Catherine Daly was valedictorian of her class at St. Teresa of Avila High School in a small blue collar city in the American Midwest. An Illinois Scholar at Trinity College and Merit Fellow at Columbia University, Daly has worked as a technical architect, officer in a Wall Street investment bank, engineer supporting the space shuttle orbiter, software developer for motion picture studios, and teacher. She lives in Los Angeles.[7]

11

A second bio appears at the front of Daly’s parody of flarf[8], the book Hello Kitty:[9]

12

The Dalys, a family founded in 1963, designed Catherine Daly in 1966. She was introduced on January 28, 1967 (thus she is an Aquarius), though her name and biography are continually expanded. She is a fifteen year post–grad living in the center of Los Angeles, CA, USA, with her family surnames Daly and Burch. Catherine Daly currently uses Olson twins hair glaze purchased at the 99 cents only store, while her sister, Elizabeth Daly, exercises more discretion. While they started out wearing nothing, in the past 25 years, Catherine wears vintage or used couture, while Elizabeth wears modish new clothes. They live a mile from each other, but 2,000 miles from their parents, Dad Tom Daly and Mom Joyce Daly. (“Kasia” is a nickname, and the source of the appellation is a maternal Polish relative, not a paternal Irish one.) Kasia is about 20 apples high and weighs about the same as 50 apples... Like her mother, she sort of plays the piano. Her favorite color is red; her favorite school subjects are english, math, and music.

13

The first bio indicates a diversity of interests and a strong technical

inclination and the second demonstrates playfulness and hilarity also

encountered in the poems.

14

The author explained the title of her book as a pun on “voice hall” (vox hall) that suggests a pleasure garden of verse (after Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens 1660–1859, London), and by her interest in the corruption of “Fox Hill” to Vauxhall,[10] “from picnic area to amusement park to auto manufacturer.”[11]

15

The title choice is appropriate to the book’s frequent use of puns, its interest in history, in the “corruption” of natural settings by intrusions of technology, and in its preoccupation with holding ideas up to the light and spinning them around asymmetrical axes to display multiplicative facets of meaning.

16

The book is divided into sixteen chapters, each of which is a poem or series of poems, as follows: “Sampler”, “Vessels: Some Forms”, “Peace”, “Golf”, “Treatise on Rudiments”, “Dance Dictionary: Directions for Bodies & Feet”, “Candy”, “The Study of Paradise”, “Heaven: An Inventory”, “Canada Place”, “Nouns off Monterey (Sardines)”, “It Has It All”, “Big Book of Birds”, “Art Art Art”, “Do You Hear What I Hear?”, and “Hook & Ornament”.

17

Some of the chapters are clearly related thematically: “Hook & Ornament” and the preceding chapter “Do You Hear What I Hear” are on the theme of Christmas; “Treatise on Rudiments” is on the theme of technical aspects of musical notation / terminology and “Dance Dictionary” is on dance technique; “The Study of Paradise” and “Heaven” have close thematic and structural ties; the next three chapters appear to form a travel log from Canada and two places in California, respectively. The author told me in private correspondence that “Nouns off Monterey (Sardines)” had been made differently from “It has it all” and “Canada Place”; the latter two, she explained, incorporated texts gathered locally and were made during travel; “Nouns” was made after the fact without using found text.

18

The overall plan for Vauxhall is not self–evident, nor is what constitutes a Vauxhall poem. The book seems to take up and lay aside subjects passing from one to the next as the eye flits across a landscape without needing to justify its motion by anything other than the interest of the moment. However, as the author explained,[12] the whole is arranged chronologically in an annual calendar, with “Candy” as a calendar–within–a–calendar, “The Study of Paradise”, written on the occasion of the birth of her husband’s writing partner’s daughter in May (not evident from the text), and the two Christmas poems at the end. It is easy to imagine each of the poems in Vauxhall as an occasion or event happening somewhere in the pleasure garden at some time of the year during the annual calendar. In fact, many of the poems are occasional.

19

Vauxhall began in 1997 in a writing workshop at Beyond

Baroque[13] where Catherine Daly

presented the poem “The Study of

Paradise”[14] in a workshop

with poet Will Alexander. After reading the poem, Alexander is said to have

remarked: ‘I don’t know what this is. So write about

seventy–two pages like this and put them together in a

book.’[15]

20

Scansion of free verse or other non–metrical verse for prosody, the identification of stress patterns into metrical feet in an attempt to identify poetic meter, though poets continue to do it and to have lively debates about its terminologies, seems to me quaint and arcane; for the purposes of understanding the music of contemporary poetry, its usefulness is doubtful. Traditional prosody has been used since Homer — almost three millennia (and possibly much longer). There’s no reason to argue about what to call an iamb that is missing the first half of its foot; it’s lame only in the context of old prosody. The conversation is relevant today as a debate about the sundial and the abacus.

21

To understand the music of spoken words, to help in creation of a new poetic

art form — for everyday speech may be heard as a rich and complex music

that we all create at will with effortless virtuosity, and when we do so

consciously may become an art — it seems preferable to me to use music

notation. What is most freeing about this approach is that it doesn’t

start out with any bias about what poetry should be; and opens the

possibility of finding out what it is. This approach facilitates new

poetic creation, gives new insight into contemporary poetic practice, and casts

new light on traditional verse. It is capable of these wonders because it turns

the attention from the written page to the spoken word.

22

“Halloween” is made up of lyric poetic bits of text inset with

rock lyrics, invented prose, and found sound gathered from reading the candy

racks from left–to–right at a Rite Aid store on the “Miracle

Mile” in the heart of Los

Angeles.[16] (This same procedure of

found sound was used in the other “Candy” poems as well; the candies

displayed changed according to the holiday.) At this point, we’ll depart

from the written text as the primary object of analysis, ignore the formatting

of the printed pages, and turn our attention to the spoken

text.[17] This analysis will use a

recording of Halloween made by Catherine Daly at Beyond Baroque, a bookstore in

Los Angeles, on October 30, 2009. I recommend that anyone interested in understanding the following transcription first listen to the recorded version of the poem (link in note 18 above) so you will know how it sounds in the poet’s voice. [18]

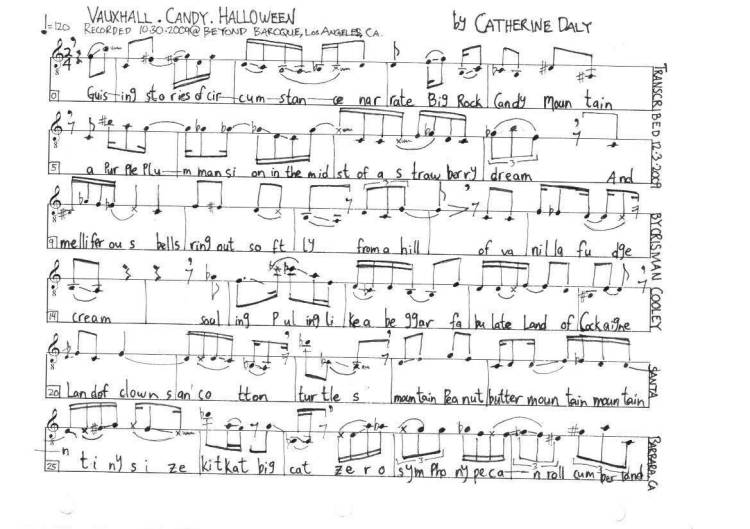

23

This transcription was made using music editing software, which allows the sound wave to be analyzed in any time and frequency increments; this grid served as a visual reference for manual transcription of rhythms into music notation. Of course as the analysis becomes more detailed, the complexity of the analysis at some point obscures the music. I’ve compromised between detail and readability, so that the rhythms should be accurate to about 1/20th of a second and the pitches should be accurate to ¼ tone (i.e., to the nearest semitone).

24

Somewhat by luck, many of the events in the poem fit extremely well within

the tempo I chose: 120 quarter notes per minute. (Meter of 2/4 time, two quarter

notes per measure, each measure equals one second.) Is it an indication of meter

in non–metrical poetry? Maybe. Or it could be pure serendipity that many

of the phrases begin on the downbeat of the first or second quarter note of each

measure. The transcription, you may notice, becomes more accurate as it goes on.

Finding the inaccuracies I suggest as a project for the reader. The

transcription of the 2’:13” (133 seconds) of the poem follows

below.

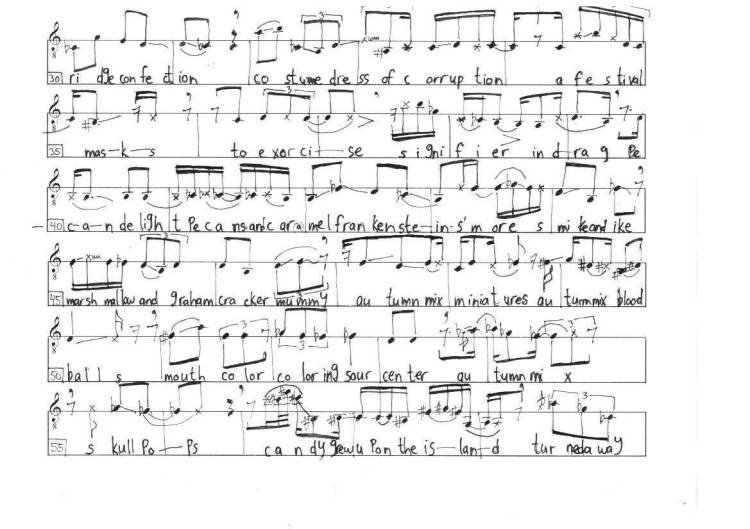

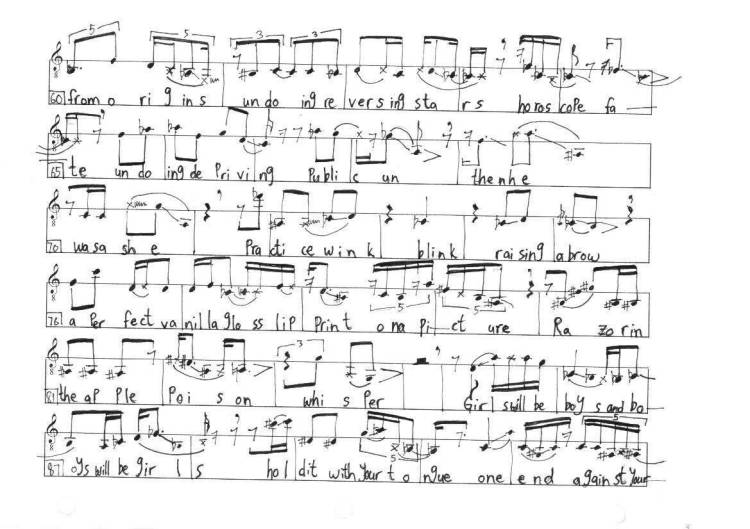

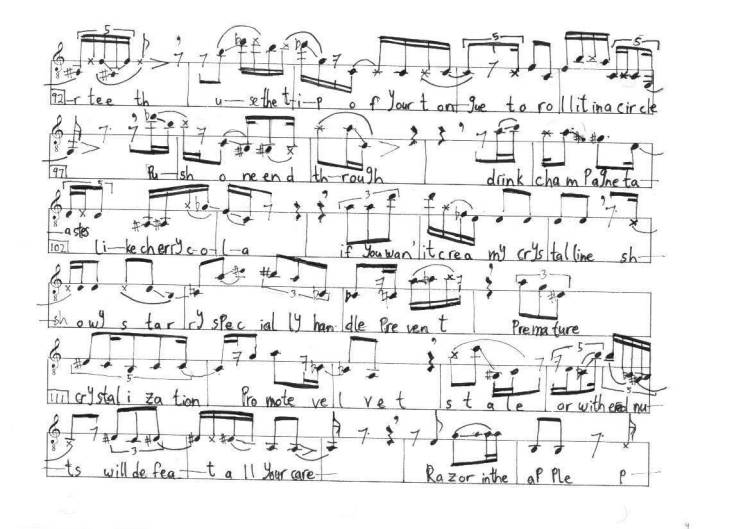

“Halloween” transcription

25

At first, I was tempted to make pitch approximate, since pitch has no place in traditional prosody; to this end, I reduced the traditional five–line staff to one line. I planned not to use pitch lines above or below ‘g’ a perfect fourth below middle C, called G3.[19] Afterwards, I was glad I notated pitch exactly on the one-line staff; it turns out that pitch variety and level was useful in understanding phrasing and accents of the performance. I chose to use the traditional starting pitch of the g– (treble) clef, down an octave. This octava treble clef is the traditional singer’s clef which is an octave lower to fit the common range of singing voices.

26

Catherine Daly has an alto voice; G3 is the approximate median of her range (though middle C may be closer to the middle of it).

27

Testing for adherence to Charles Olson’s advice from “Projective Verse”, we’ll see whether breath is the natural basis of the poetic phrase here. Using the poet’s breath as the cue for a line break in the reading of “Halloween” results in the following phrases. Each phrase is followed by its length in measures (i.e., seconds) in square brackets and the number of syllables in curly braces:

28

Guising, stories of circumstance, narrate Big Rock Candy Mountain,

[5]{16}

a purple plum mansion in the midst of a strawberry

dream[20] [3.5]{15}

And melliferous bells ring out softly from a hill [4]{13}

of vanilla fudge cream [3]{6}

souling, “puling like a beggar,” fabulate Land of Cockaigne,

[4.5]{15}

land of clowns and cotton, [2]{6}

turtles [1]{2}

mountain peanut butter mountain mountain tiny size kit cat big cat

[4.5]{17}

zero symphony pecan roll cumberland ridge confection [4.5]{15}

costume dress of corruption, [2.5]{7}

a festival mask[s][21]

[1.5]{5}

to exorcise, [1.5]{4}

signifier in drag. [2]{6}

pecan delight pecans and caramel Frankenstein s’mores mike and ike

[5.5]{16}

marshmallow and graham cracker mummy [3]{9}

autumn mix miniatures autumn mix blood balls [4]{11}

mouth [color][22] coloring sour

center [2.5]{9}

autumn mix [1.5]{3}

skull pops [2]{2}

Candy grew up on the island, [2.5]{8}

turned away from origins, undoing, reversing stars [4]{14}

horoscope — fate [2]{4}

undoing, de–priving public un, [3.5]{9}

then he was a she. [2.5]{5}

practice wink, blink, raising a brow [4.5]{8}

a perfect vanilla gloss lip print on a picture [4]{13}

Razor in the apple, poison, whisper [5]{10}

Girls will be boys and boys will be girls. [3.5]{9}

hold it with your tongue, one end against your teeth, [4.5]{11}

use the tip of your tongue to roll it in a circle, [4.5]{13}

push one end through [3]{4}

Drink champagne, tastes like cherry cola. [4]{9}

if you want it creamy crystalline, [2]{9}

showy, starry: specially handle prevent [4]{10}

premature crystallization promote velvet [3.5]{12}

“stale or withered nuts will defeat all your care” [5]{11}

Razor in the apple, poison. [3]{8}

I’m coming out. [1.5]{4}

I’m coming up. “Ring my bell.” [3.5]{7}

I’m thinking about my doorbell. [3]{8}

It is a coming of age story. [2]{8}

Total seconds = 133. Total syllables = 371. Average syllables / second =

2.8.

29

The first minute of the performance is very fast with phrases densely packed, average syllables taking 0.23 — 0.3 seconds, the minimum syllable a16th note, equivalent of 0.125 seconds. (Note that most minimum rhythmic values are not syllables, but individual phonemes.) All three of the errors occur in the first minute. Half of the linebreaks disappear and a breath (a break) appears in the middle of a line (at “hill”). After the first minute, the phrases tend more to respect the written line breaks, though some are ignored; the spacing evens out; and there are no mistakes. The speed and dense phrasing could be a matter of choice; but I would guess that, with the errors, they might be the result of performance anxiety, decreasing as the performance went on. Ending syllables had average durations from 0.4 to 0.5 seconds each.

30

When I first listened to the piece, I believed that the spoken poem was revealing the “headiness”, or disembodied quality of the poem — a common feature of contemporary “page poetry”, and no less in Vauxhall, since these poetries are most often composed and read in silence, tending to a pure mental activity.

31

As I slowed down the recording to capture the nuances of pitch and rhythm, I

became mesmerized by the theme of transvestitism and the emergence of clowns,

beggars, mummies, blood balls and skull pops as images from “The

Tempest” (“Candy grew up on the island”) and “Rocky

Horror Picture Show” (perfect vanilla gloss lip print on a picture) rose

up between candies continuously pelting from the sky.

But I’m supposed to be talking about the Expression Plane.

32

Performing this piece from the score in a way that would sound natural would be extremely difficult, as it would be difficult for virtuoso jazz organist Jimmy Smith (or anyone else) to perform a notated version of one of his improvisations. My transcription runs up against its limitations. But without a doubt, this is a virtuoso performance. Like the miracle of birth, the miracle of speech — the complexity we can create without even thinking about it — is truly astonishing. So the first gift of this transcription is the recognition of excellence and complexity of the reading, imbued with all subtleties of native speech.

33

Here are instructions that would be needed by a performer:

34

The single staff line, G3;

Other staff lines are left off to indicate that this is a spoken

performance;

Unlike a song, where notes are held on pitch, in speech pitches change

continuously most of the time;

This piece should be performed in sing-song speech, so that most notes have

portamenti natural to American English intonation, slightly exaggerated for

effect;

All syllables are marked with ties;

Lines between notes indicate portamenti;

Notes within slurs are single syllables and should not be individually

sounded but should be part of the gliding pitch of a portamento or

portamenti;

“X”–marked notes are fricatives, unvoiced consonants;

Scratch marks after a note or after an “X” note indicate

continuation of a fricative for the marked duration;

Notes are exact pitch (semitone granularity), but need not be exactly

sung;

Large “commas” are breath markings;

Ties are often within slur marks of a single syllable;

Lyrics are indicated below notes to which they belong;

Sometimes sounds from adjacent words are combined into a syllable, in which

case their letters are contiguous.

35

Some notable features: Daly’s vocal range in this piece is from b–flat below G3 up to g–flat, a half–step below G4 — a full octave and a minor sixth, quite large for a speaking voice. Her variety is part of what makes her performance interesting. The triplet at “dream” is remarkable — how the poet’s voice jumps up a major third mid–word. There is remarkable pitch variation throughout, featuring compelling sing-song intonation. Though there is no pulse, no sense that the poet is feeling a beat, the phrases have a musical flow. Using 2/4 time at quarter note = 120, as mentioned, achieves a remarkable consistency of downbeats, which makes it seem like there is a pulse underneath.

36

A clear example of using intonation to distinguish phrasing occurs at measure 57, (measure numbers are in the lower left–hand corner of measures left–adjusted on the page) at the phrase “Candy grew up...” where she jumps (up from g–flat G3 — measure 55–56) up an octave to F–sharp (G4 octave), then dives all the way down to d–sharp below G3. The previous phrase has been hovering around G3 for the whole duration up to that point. This marks a change on the content plane and the introduction of a protagonist, Candy.

37

Parallel word repetitions repeat the same rhythms at “Razor” (measure 80–82 & 119–121), a clear sign of structure affecting rhythm.

38

Throughout the piece, rhythmic figures appear contiguous to each other, separate and distinct from other rhythms:

39

Eighth notes: measures 0–1; 10–11; 22–23; 30–32;

42–44; 55–56; 71–76; 105–107;120–121.

Sixteenth notes: measures 1–2; 6–7; 17–19; 24–27;

57–59; 62–63; 93–94; 130;

Syncopated eighth notes: measures 47–49;

Triplets: measures 28–29; 51–52; 61; 108–110;

Quintuplets: measures 34–36; 60; 78–79; 91–92; 95–96;

115.

40

These repetitions may be coincidental, but a simpler explanation is that the poet structures the rhythmic performance around the repetition of rhythmic figures. It is interesting to note that these rhythmic structures have less meaning outside of the assumption of a pulse of some kind.

41

Alternatively, they could be considered merely as similar quantities of time, in which case some of the above examples would be eliminated. For example, a sixteenth note inside a quintuplet at this tempo (120 quarter notes per minute) equals 0.1 seconds. Look at measure 60 for example: a dotted eighth note quintuplet (0.3 seconds) is followed by an eighth note quintuplet (0.2 seconds); then two sixteenth note quintuplets (0.1 seconds each) are followed by an eighth note (0.2 seconds) followed by another sixteenth note quintuplet (0.1 seconds). This series of rhythms are almost certainly not sensed by the poet in relation to a beat; that is, they are not sensed as quintuplets.

42

Yet most of the contiguous rhythms noted above would be noticeable as pure durations. So we have the curious situation of order for which there is no definite explanation. Is the poet (as reader) sensing a pulse? Do any of us sense a pulse when we read non–metrical literature? Do we sense a pulse with metrical poetry? If so, how? We cannot adequately answer these questions here.

43

Much more could be said about accents, these being much ballyhooed in traditional prosody. After close inspection of the transcribed score (poem–as–musical–piece), the fact emerges that every occurrence of accented syllables, every occurrence — with only two exceptions — the accented syllable is pronounced at a higher pitch. That’s a 99.5% correlation (2 syllables out of 371 total). Using pitch, it is likewise possible to choose which accent is strongest in a phrase, merely by noting which pitch is higher.

44

The only exceptions to these rules are measures 119, the word “Razor” where the first syllable is an F and the second is A a major third above it; and ms 122 “coming”, where the first syllable is F–sharp, and the second is G. How many disputes of prosody could be resolved if pitch were included in the discussion?

45

We have not transcribed amplitude, or dynamic level as it is called in music. It would be easy to do, since the wave shape in music editing software is based on a measure of pressure, the compression and rarefaction of air that is the sound wave.[23] It would be beneficial in a more complete scientific / musical discussion of prosody to include this information. When that work is done, it will be interesting to inquire into the relationship between pitch, rhythm, and dynamic level and how these are related to traditional concepts of stress or accent, plus patterns of pitches, rhythms, and dynamics and how they are related to the metaconcepts of meters and entire forms. My intuition is that these relationships are the prosody, and, once understood, hold the key to esthetics of the expression plane.

46

For now, we will content ourselves with having discovered that:

1) It is possible to accurately notate a poetic performance;

2) Pitch is intimately bound up with syllabic accent;

3) In-breath marks the line break;

4) An intuitive musical order, of both pitch and rhythm, underlies this

specific poetic performance.

47

“Halloween” is perhaps the most interesting poem on the content plane in the “Candy” series. The outset text begins, as we’ve seen, “Guising, stories of circumstance, / narrate Big Rock Candy Mountain.” According to OED, the word ‘guising’ means first ‘to attire fantastically’, in addition to being a synonym for disguise — a perfect word choice for the occasion. As we see in “Sampler”, “Vessels”, and elsewhere in the book, this poet has a large, fine–grained, and accurately deployed lexicon.

48

The outset text is followed by a quote from a song, but not the one named: “...a purple plum mansion / In the midst of a strawberry stream...” The lyric is from “I enjoy being a boy” by the rock band Queers. The choice is auspicious, being a forerunner to the introduction of the ‘protagonist’ Candy, and setting up later references in the poem to lyrics of Kinks “Lola” (“Drink champagne tastes like cherry cola” and “Girls will be boys and boys will be girls”) and Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Wild Side” (“then he was a she”), both of which are about transvestites. Of course, at Halloween boys (or men) are sanctioned by the culture to dress as women for one evening.

49

But the opening stanza promises that guising and stories of circumstance are going to be about “Big Rock Candy Mountain”. I didn’t understand the connection at first, except that BRCM is a place with soda pop lakes and peppermint trees: a child’s candy paradise. Children draw pictures of this place; some continue to do so until they’re teenagers. So there’s a connection to all the candy raining from the sky throughout the poem.

50

All the poems display an awareness of history — no less “Halloween”. Daly traces the story back with the reference to Cockaigne. Of this, Wikipedia says:

51

Cockaigne (pronounced /kɒˈkeɪn/) is a medieval mythical land of plenty, an imaginary place of extreme luxury and ease where physical comforts and pleasures are always immediately at hand and where the harshness of medieval peasant life does not exist. Specifically, in poems like “The Land of Cockaigne”, Cockaigne is a land of contraries, where all the restrictions of society are defied (abbots beaten by their monks), sexual liberty is open (nuns flipped over to show their bottoms), and food is plentiful (skies that rain cheeses).[24]

52

Likewise, Big Rock Candy Mountain was invoked from dearth of the Depression in USA, painting a picture of a hobo’s paradise. The lakes that became soda pop were originally of whiskey and gin and instead of peppermint, the trees grew cigarettes. In one particularly colorful and relevant telling of the song, a hobo invites a boy to come along with him to the promised paradise of BRCM. Six months later, the boy manages to escape the hobo and return home, saying:

53

“There are no bees in the cigarette trees,

No big rock candy mountains,

No chocolate heights where they give away kites,

Or sody–water fountains.

...

“He [the hobo] made me beg and sit on his peg

And he called me his jocker.

When I didn’t get pies he blacked my eyes

And called me his

apple-knocker.”[25]

54

So this boy, call him Candy, was promised a paradise of sweetness and becomes instead a hobo’s “jocker” (according to OED, “A tramp who is accompanied by a youth who begs for him or acts as his catamite;” or, alternately, “a male homosexual”).

55

Halloween has always (to my mind) been associated with danger, with tricks or treats, with the supernatural, with death and the devil. As kids we were warned to beware and even to refuse apples because they might contain razors and of homebaked goods because they might be poisoned. Today most kids younger than thirteen are not allowed to go out trickertreating without accompaniment by an adult. “Razor in the apple, poison.”

56

The danger is only suggested, though. As usual with this poet, she passes right by the heavy consequences that would be associated with a literal backstory (like Laurence Sterne, she’s unaffected by gravity) and goes directly into jokes about “premature crystallization” and the one that makes me laugh out loud, “...withered nuts will defeat all your care”.

57

“Sampler”, “Vessels: Some Forms”, “Peace”, “Golf”, and “Sixlet”

An analysis of some features of expression and content planes of five poems

from Vauxhall follows. The analysis is informal and intuitive.

58

Given the lack of thematic linkage between the poems, the first poem “Sampler” nonetheless contains a metaphor of the poet as seamstress (or semestress), suggesting a context to explain the effort of all the poems. It is doubtful whether this is the author’s intention for the entire book, but it seems the likely preoccupation of this poem, which begins, “If I sew, is it / psychic embroidery?”

59

In the 17th through the 19th centuries in the Netherlands, young Dutch girls began sewing at 10 years old. They would sew “...[three different] samplers which, when completed, would be shown to a future husband to prove what a good wife she would make him.”[26] She would embroider and initial the bedsheet the newlyweds would use on their wedding night. “In a wealthy family the daughter was able to stay home and stitch additional samplers and items. The more needlework a young girl had to bring to her own future household signified her coming from a ‘privileged lifestyle’ and that she did not need to work outside the home to aide her family financially.”[27]

60

Sewing becomes a metaphor for writing poetry, and both become the antecedent to sexual union: “...while her fingers move, / engage her heart. Write: she and you. ... Seek love, your love, / love of you. Write your name on her heart. She will.”

61

The poem, like many Vauxhall poems, uses outset and inset text forming a kind of call and response form, with the call or question formatted flush left and the response indented. Of this structure, the poet says: “I was thinking of the Vauxhall poems in general as being standalone, more augustine poems on the left margin, with inset text of wilder stuff. ...it also became the way to amp up the lyricism in Locket, and it set me up for the device and some of the poems in the DaDaDa sequel...”[28] Having established this theme (of sewing a sampler) and this form, the poet begins what occurs to me as a theme–and–variations or seme–and–variations improvisation:

62

“A simple strip of cloth, a reference

of standard stitches”

become an opportunity

for indoctrination up tammy, tiffany gauze, linsey– woolsey:

a show towel, symbol of cleanliness, paradenhandtuch,

parade for the hand to touch, Pentateuch. When you read this,

remember touching me. No, virtue ‘each sense and satiate

each.’

63

This riffing is a very curious blend of sound and sense. “Indoctrination” has to do with the permanent affixture of words, perhaps advice, onto a substrate in this case cloth of three kinds: tammy, etc. These cloths are suggested as towels, “a symbol of cleanliness” (both symbol and purposeful, as the bed sheets). “...paradenhandtuch” seems to be a coinage of a German noun (only two occurrences in Google, one of them this poem), meaning literally “parade towel”, which she translates, then riffs into “Pentateuch”, an alliterative word that sort of rhymes and combines also the notion of religious indoctrination, being the Torah, or Jewish law and also the first five books of the Christian Old Testament.

64

Because this passage is characteristic of a lot of Vauxhall, it’s worth saying a bit more about it. The style reminds me of jazz improvisation in at least three senses: first, because it is relaxed — making what is difficult seem easy; second, it emphasizes immediacy over perfection; and third, the theme–and–variations riffing on both sound and sense.

65

The cloth types are an example of this third point, of sound–and–sense riffing:[29] “...tammy, tiffany gauze, linsey–woolsey...” are sense variations on the theme of cloth and sound variations on words ending with an [i] sound[30] and beginning with [t]; however the [t] alliteration is interrupted at the word ‘gauze’, where the interest is transferred to the internal [z] sound.

66

The inset section contains two quotes: “ ‘Give me your early trace’ and ‘youthful stuffy’ / not pouncing.” Neither of these quotes occurs in Google anywhere but in Vauxhall (or links to young people’s antihistamines). We’ve seen numerous real quotes already, but here they are as impossible to decipher as quotes or free inventions. In the jazz metaphor, she is “playing out”, those phrases having a complex relationship to what is being discussed. And I admit: I have no idea what she is talking about.

67

The fourth response stanza begins: “Queen’s, Holbein, Gobelin, Montenegrin cross– / stitch. ‘Cross a mercy.’ Roumanian couching, / encroaching satin stitch. / ‘Cross a mercy.’ ” The first four nouns end with ‘n’/‘n’s’ giving the characteristic sound to the line and each may be supposed to have something to do with sewing (though Holbein is known as a printmaker, so any reference is lost on me), Gobelin is Parisian factory of tapestry and Montenegrin is a close–fitting woman’s garment. The second of the two “crosses” is possibly a quote from John Newton’s 1775 poem “A Memorial of the Unchangeable Goodness of God, under Changing Dispensation”.

68

The stanza ends as follows:

69

...Knottedoek,

not dreck nor daisy, not docked or decked, knotted to death.

A french knot, pulled, means ‘yes’. ‘You know well enough

what I mean.’

70

Notable here the alliteration and internal rhyming, again, riffing on “doeck” to “dreck”, “docked”, “decked”, ending in “death”. The reference to the French knot, supposing it to be equivalent to a Dutch knot, is explained:

71

“...knottedoek (literally knotted doek/cloth) a square linen kerchief or cloth embroidered in cross–stitch that was used to hold the dowry (100 silver sixpences) when a girl’s hand was asked in marriage. The kerchief embellished with a rhyme, we offered to her loosely knotted. If she pulled the knot tight it meant her answer to the proposal was ‘yes!’[31]

72

This sequence displays to great advantage how the poet’s use of puns actually leads to a number of possible readings. ‘Knotted to death’ could mean ‘containing too many knots’; or it could mean — coming after so many negatives — ‘erased’ by a surplus of nothing; or it could mean married (tied the knot) ‘till death do us part’; or it could mean suffocation from an excess of closeness; etc.

73

The next left–adjusted call is: “Seam– / stresses seem semes,” giving the clue to the poem. Then “divine songs” is followed by quotes from Thomson’s Poems “sacred substantial”, Ethel Stanwood Bottom (1807) “unknown accidents your Steps attend”, and Alexander Pope “Day be bread.”

74

That is followed by “and Milton’s, and in the Book / of Numbers”, the response to which is: “spies of the green tree flee the walled city. / Promise is also a dry stick. / The spinning monkey blowing bubbles is fated to the / spindle.” Is it nonsense? The only clue is that the “spinning monkey” is an established sewing sampler motif. Sampler motifs were often iconic, that is, both images of animals, deities, or other figures, but also a sacred personage. A “spinning monkey” is an iconic representation of the Devil, standing for folly, laziness, lechery, and vanity. His punishment is that he will be turned into thread.

75

At this point, it becomes clear that the quotes throughout may be considered

phrases stitched into the sampler and that the other images, like the

“virgin’s cat”, “King of Mirrors” etc., are iconic

figures in cloth. Thus, the seamstresses become the wielders of the power of the

word and the image, which they can sew into all of the linens for all time

— their messages becoming permanent part of someone else’s life and

legacy: “Utilitarian, needlewomen / remind and mend, darn and damn.”

And the poet, like the needlewomen, has the power to create a lasting identity

in verse: “Here you see my / name, complete.”

76

The second poem, “Vessels: Some Forms”, is in three sections: Glass Glasses or Goblets; Tumblers and Cups; Decanters. The first text of the three is in the shape of an upside–down wineglass (the way they are stored in the cupboard); the fact may be incidental or accidental — though I doubt it. The poet uses this subject as a way of commenting about the vessel itself: “delicate”, “enduring beauty”; about alcohol: “rum was lower class”; about people who drink: “blowsy if you like it/ ruddy cheeked”; how the vessel was made: “free–blown”, “no bubbles a sign of workmanship” ; uses of the vessel: “wineglass”, “rummer” (from Dutch ‘roemer’ = ‘seaman’), “glasshouse flowerer”; the shape: “hourglass–shaped”, “round–bottomed bowl”, “corset”, “woman” with “buttonlike knop”. These shapes are also the shape of the text itself.

77

The text shows how the poet takes a mundane subject and through extension in

sound, shape, history, etymology, fashions something interesting and

multidimensional.

78

The poem begins with a paraphrase of Romans 10:15: “How beautiful the feet of whom publishes peace.”[32] Unlike most other poems in Vauxhall, “Peace” is all left–indented with no inset text. Structurally, it hangs together on the feeble tension of a string of puns and rhymes, each explored and sometimes belabored in a series of sections: “Peace”, “Peas”, “Knees / Make Love not War”, “Fleas”, “Lease”, “Peace, Please”, “Piece”, “Cease / Keats”, “Plea for Peace”.

79

Raymond Roussel, I believe, was the first to use the pun, not as mere ornament, but as a primary element in literary structure. In “Peace”, Catherine Daly follows suit. But the device relies upon the freshness of the association for its tensile strength and cognitive blast. “Peace” has an extended set of puns on peace/peas beginning on line 17 to the end of “Peace” and continuing all the way through the next section, called “Peas”, a full page–and–a–half. This is unfortunate, to my ears. The bumper sticker “imagine whirled peas”, though it was amusing at the time, has passed beyond cliché and the bumpers of all the cars that once carried that message are in the auto wreck yard. “Shelling peace”, “snow peace”, “black–eyed peace”, “split peace”, “chick peace”, “give peas a chance”, “rust in peas” litter the pleasure garden.

80

The phrase in the first line “a pound of peace” may be playing with similar phrases: “a pound of cure” and “a pound of flesh”. The first refers to Ben Franklin’s saying “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”, which was advice to citizens for fire prevention. The second refers to Shylock in Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice”:

81

Shylock.

Most learnèd judge, a sentence! Come prepare!

Portia.

Tarry a little, there is something else.

This bond doth give thee here no jot of blood;

The words expressly are “a pound of flesh.”

82

The “pound of peace per couple” appears to be a kind of advice to the maker of couples (God, Cupid, Venus, whoever) that in addition to the two hundred plus pounds of what is not peace, include a pound that is. But this interpretation is dubious.

83

“...peace has been carbon–dated 9750 / B.C.E.” is a funny line, indicating in an amusing way that there’s been no peace for about 12,000 years. Behind the joke is an intellectual observation that has no objective emotional correlative for most people living within the borders of the USA today. It is a statistic, like a pitcher’s earned run average, not something we’ve experienced inside our borders.

84

What is the poet saying? Clearly, there is little in “Peace” of

political, social, philosophical, psychological interest, or we could say, in

the interest of consciousness. Is there esthetic interest? Can there be esthetic

interest without any moral basis? Can’t answer that in a short essay...

And consciousness is first of all consciousness of the senses, which we find

little of in this very intellectual poet. But let’s keep these questions

in mind as we search forward for all things beautiful.

85

We have seen that the different subjects in Vauxhall (themes, that is, of the respective poems) are not necessarily related to the what the theme is, but seem to have more to do with punning, playing with language, free associating, googling, ogling, etc. Whereas golf, for example, had been a good walk, spoiled — we cannot say what it will be inside Vauxhall.

86

The poem has two sections: Play and Three Attitudes. The first salvo is, “Anything with a ball / any game Life’s a game, / lends itself to puns. / fun golf is serious.” As with “Peace”, the preoccupation is with puns, language fun, and jokes. The line: “fun golf is serious” can be read either as “fun golf is serious” or “puns. / fun golf [on the other hand] is serious.” And I would argue that this ambivalence is part of Daly’s charm. She means both; the one as an observation (that golfing is more fun when you take it seriously), and the other that punning in poetry is fun.

87

The punning starts right off with the line “Play it as it lays”. It continues:

88

‘A young woman with long hair and a short

white halter walks...’

...as you find it,

‘Under the greenwood tree

Who loves to lie with me

come hither, come hither, come hither...’

”[33]

89

This is another charm: golf turns suddenly to love under the greenwood tree. “As you find it” is a very good joke, both because the ball doesn’t often end up “As you like it” and also to tie in the source of the greenwood tree.

90

Later, another notable series of left turns:

91

Style:

textbook

orthodox swing

(just picture it)

‘On Herod’s birthday, the daughter of Herodias

danced before them and pleased

Herod.’[34]

torturous charade

alternate route

enthralled by executing original

intention

Mind if I join your threesome?

92

Picturing a textbook golf swing, the image suddenly turns into a scene of Herod’s daughter delighting a company of friends by dancing. To understand the next four lines, beginning with “torturous charade” (which appear to be nonsensical otherwise), we’ll have to recall what happened next at Herod’s party. “[The dance] so delighted Herod that he promised on oath to give [his daughter] anything she asked. Prompted by her mother she said, ‘Give me John the Baptist’s head, here, on a dish.’ ”[35]

93

Questions come to mind: Is the golf swing related to the stroke of an axe? Or do “textbook / orthodox swing” actually refer to a handbook of executioners? In light of this, consider: “Mind if I join your threesome?” Suddenly golf, a plattered head, and ménage à trois (quatre?) collapse into one — but in a deft and facile manner so that every expression has a more innocent golfy interpretation.

94

Many other poems in this collection I’ve only mentioned briefly. There

is a great deal here still to discover.

95

In Vauxhall, we encounter a poet who is at once funny, charming, dangerous, erotic, and playful. She knows but does not lament history. She makes her curious nest out of everything she finds, from arcane literary bits to trashy clichés. She appears to be able to create with ease from this bizarre mixture pieces of extraordinary beauty.

96

Transcribing the poem “Halloween” was immensely entertaining. The

poet’s spoken voice embodies her voice on the page. Listening to her voice

slowed down seems to reveal new layers of mystery and meaning in her work, and

to reveal the poem’s wickedness, musical virtuosity, and infinitely light

touch. She has somehow found a pathway through the maze of modern life, in her

work and in her poetry. She seems a kind of oracle of the new: she is not afraid

of Rite Aid; she is devoid of lessons, which gives her voice frightful clarity

and shows us a bit of the world’s chaos and meaninglessness with no hint

of despair.

[1] CP Snow said that the divide between science and humanities was a major obstacle to solving world problems. CP Snow, “The Two Cultures”, Rede Lecture, 1959.

[2] Certain famous examples of semiotic textual criticism, such as S/Z by Roland Barthes, which attempts to make the review a work of art in itself, seem to me confusing as criticism and failures as art. This is a critical essay.

[3] Louis Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, trans. F. Whitfield, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1963 [1943].

[4] For more on the distinction between expression and content as the two levels of linguistic communication, see Hjelmslev, L. 1943. “Omkring sprogteoriens grundlaeggelse”. Copenhagen. 1961.

[5] It isn’t form that makes beautiful formal verse beautiful. Traditional prosody, come to think of it, is useless in describing the esthetic of its object.

[6] Dana Gioia said that New Formalism was a reaction against “...the debasement of poetic language; the prolixity of the lyric; the bankruptcy of the confessional mode; the inability to establish a meaningful aesthetic for new poetic narrative and the denial of a musical texture in the contemporary poem.” Dana Gioia, “Notes on New Formalism”, The Hudson Review (40, 3, 1987)

[7] http://www.ahadadabooks.com/content/view/60/41/

[8] Described by one flarfist as too flarfy not to be real flarf. “No,” Ms. Daly says, smiling, “I was making fun of you guys.”

[9] Catherine Daly, 2007, Ahadadabooks, http://www.ahadadabooks.com/content/view/60/41/

[10] According to wikipedia, this is a slight misconstruction: “It is generally accepted that the etymology of Vauxhall is from the name of Falkes de Breauté, the head of King John's mercenaries, who owned a large house in the area which was referred to as Faulke's Hall, later Foxhall, and eventually Vauxhall.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vauxhall

[11] Email correspondence with the author, Aug 7, 2009. In reference to the evolution of Vauxhall: Vauxhall Motors is a subsidiary of GM, spun off two days before the parent company — as the ‘Pleasure Gardens’ had done 150 years before — declared bankruptcy.

[12] Email correspondence with the author, Nov 24, 2009.

[13] http://www.beyondbaroque.org/

[14] http://sites.google.com/site/cabdaly/Home/Paradise-20091030.mp3

[15]Same as above.

[16] Related by Catherine Daly in introduction to the reading recorded at Beyond Baroque in Los Angeles, October 30, 2009.

[17] A poem (or any text for that matter) may be considered a musical score that is highly indeterminate of its performance. Traditional verse, as Yeats explained, was to be sung in verse; and there are recorded examples of what Yeats and Pound thought this singing should be. Contemporary free–verse or other–verse, outside syllabic accents and intonation of native spoken English, give no rhythmic, intonational, or accentual guidance. This does not seem to matter very much to most poets today.

[18] http://sites.google.com/site/cabdaly/Home/Halloween-20091030.mp3

[19] Called g in Helmholtz designation or G3 in Scientific designation. The frequency of this pitch is 195.998. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies

[20] The text says “stream”, but the poet pronounces “dream”; one of several minor performance errors.

[21] A second error, (“masks” instead of “mask”) which causes the poet to take a breath at an unusual spot.

[22] The last performance error, saying “color”, then correcting herself to “coloring”.

[23] The sound wave digitized in fact is made of a series of measurements of pressure — 44,100 of them per second for “CD” quality.

[24] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cockaigne

[25] http://sniff.numachi.com/~rickheit/dtrad/pages/tiBIGROCK3;ttBIGROCK.html

[26] Lucy Lyons Willis, “Dutch Samplers: Embroidery in the Netherlands” http://lachatelainedesigns.homestead.com/dutchsamplerhistory.html, 2001

[27] Same as previous. In 21st century America, few activities belie the ‘privileged lifestyle’ better than poetry since not only does writing it pay almost nothing, it also takes a lot of time that could be spent in better-paying activities. This is probably true of embroidery today in the Netherlands, since it is cheaper to buy it from China.

[28] Email correspondence with the Catherine Daly. The sequel alluded to is Object Oriented Design, forthcoming.

[29] Riffing usually means a repeated figure over changing chords, but here I’ll use it to mean sound and sense theme and variation.

[30] The brackets indicate phonemes of the International Phonetic Alphabet, in which system [i] = “ee”.

[31] “Dutch Samplers: Embroidery in the Netherlands” by Lucy Lyons Willis http://lachatelainedesigns.homestead.comdutchsamplerhistory.html

[32] The quote is changed so that if you Google the exact quote, Daly’s usage is the only one that comes up. The quote is, “How beautiful are the feet of the messenger of good news.” (New Jerusalem Bible, p1882, 1985)

[33] Quote is from Shakespeare’s song “Under the Greenwood Tree” from “As You Like It”.

[34] Matthew 14:6, New American Standard Bible, 1995.

[35] Matthew 14:6, New Jerusalem Bible, 1985.

Catherine Daly

Catherine Daly was valedictorian of her class at St. Teresa of Avila High School in a small blue collar city in the American Midwest. An Illinois Scholar at Trinity College and Merit Fellow at Columbia University, Daly has worked as a technical architect, officer in a Wall Street investment bank, engineer supporting the space shuttle orbiter, software developer for motion picture studios, and teacher. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband. She is the author of seven collections of poetry.

Crisman Cooley

Crisman Cooley was first in the US to earn a degree in Semiotics from somewhere other than Brown University. For this, he earned chastisement from his college President and employment from a bemused Washington lawyer. Mr. Cooley is a playwright and essayist who translates poetry from French, Spanish, and Anglo Saxon and teaches contact improvisation. He lives in Santa Barbara, California with his wife and two daughters.