| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Michael Cross and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-cole-rb-cross.shtml

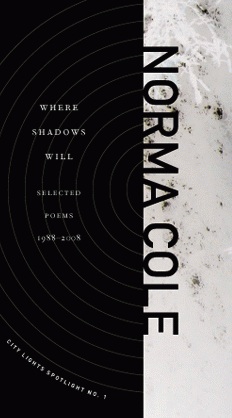

Norma Cole

Where Shadows Will: Selected Poems 1988–2008

reviewed by

Michael Cross

City Lights Publishers ISBN: 9780872864740 PAPERBACK USD 14.95

1

In her Manifesto (1969), Agnes Denes argues

2

… that everything has further meaning,

that order has been created out of chaos,

but order, when it reaches a certain totality

must be shattered by new disorder

3

Denes privileges the comportment of artist to environment in order to track the effect of thought in space, or put differently, thought’s affect in space. Her interest in the consequence of interface stems from a critical eye to the sometimes glacial movement of entropy complicated by the artist’s desire to establish temporary order, even if it is made to be dismantled and built again. Or as she has it in “Study of Distortions” the following year, “Add to [distortions of form] the constant puzzle of having to deal with the discernible aspects or appearances of things, conditions, people, and events — not their ultimate essences or ideal states” (9). Rather than reduce experience to mere phenomenology, Denes practices framing environments, and here I mean systems, landscapes, echo chambers, social and political configurations, the surface of the page — what Denes calls “discernible aspects or appearances of things” — in order to commit to confluence in flux as flux.

4

Reading Denes intervention next to Norma Cole’s timely selected poems, Where Shadows Will, the inaugural publication of City Lights’ “Spotlight Series” (shining “a light on the wealth of innovative American poetry being written today”) is incredibly instructive. Where Shadows Will tracks Cole through twenty years of careful conceptual practice, an omnibus that reveals (more than any of her single publications alone) how poetry might begin to address the concerns of late 70s conceptual art. As a visual artist herself (and materialist to boot), Cole sees words as both conceptual and visual elements, so just as “painting is thinking,” the poem is thinking as painting, a troubled string of causality further complicated in context:

5

news flies through the air with a great constriction below

the throat

false distance puts the teeth back in

the singer reads absence backwards

resting close

in is by means of a phone in the drawer by the bed

the painting is thinking the weather goes dry and flat

this fold carried by air contains no other object (10)

6

Here the notion that “painting is thinking” is both aesthetic argument and literal fact — the painting is thinking in that it thinks “the weather goes dry and flat.” Or in ‘Allegory Fourteen” from Moira, in which Cole writes, “By consideration of our / national stone or anticipation / of our building an idea of it,” we find the building of the idea as well as the poem as building or foundation, idea, and maquette — not the building in actu realized as end, but a model of an idea of it. Her poetry rivals the best conceptual architecture as it too exists to address the problem of social and political engagement, despite the possible impossibility of its existence in space. For Cole, however, that the poem can’t do all that it promises and does it anyway is the conflict of the project writ large. And even with “cement, glass, silicone, polymer” holding together the untenable, like Denes, Cole’s language is built on the presupposition that the idea should stand only to be dismantled to first matter and built again. The poem then is a model of manifest thought, each glued and fabricated line sensing through the flaw of its impossibility, teetering on the hope of a possible future.

7

As such, these maquettes serve to track thought as it moves in the critical environment of the white page in order to exhaust its possibility and investigate the means — to learn from the struggle. In “He Dreams of Me,” Cole again addresses the project as a whole: “Design problems move. Survival means in each case not to resist movement or where one is in it” (65). To interface with the poem (to read or to write it) means to accept its labyrinth of meaning, its predilection toward excess, so that, as Lacoue-Labarthe has it “Poetry is not a catastrophe of catastrophe. But, because it aggravates the catastrophe itself, it is, one might say, its literalization” (51). Cole’s poetry brazenly pulls back the curtain of the present to track where the sheen of “truth” begins to craze, the result of which is a literalization of conflict in which the poem attains a kind of surrealist immediacy; which is not to say, however, that the poem depends on the logic of dream for abstraction (i.e. as crutch), but that it is

8

dreamlike not in the sense of

being vague but

rather in its clarity and vividness

9

These poems are not about the catastrophe of static subjectivity or the catastrophe of enframed objectivity where reification serves to package and sell experience; instead they test the catastrophe to mobilize the conditions of being for readers to track “where (they are) in it,” a vividness and locked-jaw moxie showing patterns “recognizable, consumable, or renewable” (78).

10

This is where I most want to place Cole in the trajectory of environmental art and its concerns. She writes in “Of Human Bodies,” “the water was a bit disturbed when the ring fell in” (62). Unlike a poet trying to capture being as interpretation-cum-observation, Cole’s poems are neither the water nor the ring — they are the confluence of action(s), the waves of disturbance beating against the frame of the page. She writes in “We Address,”

11

I was born in a city between colored wrappers

I was born in a city the color of steam, between two pillars, between

pillars and curtains, it was up to me to pull the splinters out of the

child’s feet

I want to wake up and see you sea green and leaf green, the problem

of ripeness. On Monday I wrote it out, grayed out. In that case spirit

was terminology

In that case meant all we could do. Very slowly, brighter, difficult and

darker. Very bright and slowly. Quietly lions or tigers on a black

ground, here the sea is ice, wine is ice

I am in your state now. They compared white with red. So they hung

the numbers and colors from upthrusting branches. The problem

was light (31)

12

Lines like waves witness event, literalizing consequence as the embodiment of being-in-the-world-with-others, not as stenographer, but as unstable subject equally implicated and responsible. The result is a poetry incredibly vivid and clear and dreamlike; in place, resting and moving; catastrophe and its literalization — a space to begin to understand a space to begin to understand.

13

For Cole, “The trip was through the lake and the lake was in the heart” (64): the trip was through the heart of the lake, read the heart of the subject, read the heart of the problem. “Experience” then echoes Lacoue-Labarthe: as we “understand the word in its strict sense — the Latin ex-periri, a crossing through danger” (18):

14

the perfect life

in a series

of measured gestures

an invitation to

see the world

from a bridge

that burns in

the next night

15

To see the world from a provisionary position that will have no longer existed, that cannot stand as evidence of existence once it’s piled in ash as the ruin of experience. Now we might measure our gestures in careful series, though we know well enough that tomorrow these very gestures will not sense under the weight of our future catastrophe — that gestures themselves will serve (as) their own undoing.

16

More than most selected poems in recent memory, Where Shadows Will serves to make an argument for an aesthetic practice, or at least for a way (or ways) of reading. Rather than serve her constituents two decades of greatest hits, Cole presents manners of approach that themselves constellate, reify, deconstruct before we’ve anchored them down. This book makes a persuasive argument for a selection produced by the author herself, if only to challenge twenty years of the entrenched reading habits of her audience.

Michael Cross

Michael Cross is the author of In Felt Treeling (Chax), editor of Atticus/Finch Chapbooks, and co-editor of ON: Contemporary Practice. He is finishing a book on Louis Zukofsky.