| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 4 printed pages long.

It is copyright © John Findura and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-brossard-n-rb-findura.shtml

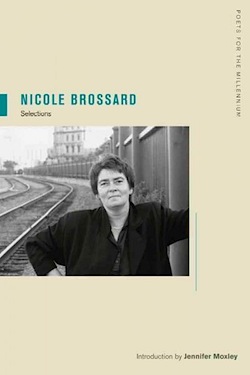

Nicole Brossard

Selections

reviewed by

John Findura

252 pp. University of California Press. US 22.95. 9780520261082 paper

1

Nicole Brossard has flown below many readers poetic radar for many years and many reasons. It’s easy to label her poetry ‘feminist’ or ‘Lesbian’, which she actually labels herself, ‘experimental’ or even the inclusive-sounding-in-name-only ‘post-avant’. The main reason she is not widely read in the English speaking world, however, is because Selections is her first collection translated into English from the Quebecois she writes in. Quebecois is curious in itself as English speakers give it the same nod as French while the French view it as nothing short of a bastardization of their beautiful Romance language. In that way, with its shunned aspect, it’s almost a natural carrier of the language of poetry.

2

All of the labels and the language controversies are quickly pushed to the side the moment one begins reading Selections and wondering why it never existed before this. From the first line, ‘neutral the world envelops me neutral’, where the enveloping world and the poet seem to be the only real things in the universe, what follows is a text lush with sensuality and sharp angles, precise and lacking fear. Even through translation it’s impossible to fail to notice Brossard’s control of words: the way they hold together with obvious strength yet create delicate movements as well.

3

In the poem ‘Contemporary’ Brossard speaks of ‘our gift for aggravating beauty’. This seems to be a typical Brossardian line that may function even better in English than it does in French. Brossard loves word play, and Jennifer Moxley’s extraordinarily enlightening introduction digs deep into the unique way Brossard uses French homophones. In translation, obviously, these are lost. In the case of the line in ‘Contemporary’, however, I love how the word ‘aggravating’ can be read as either a verb or an adjective — in either case making the line successful against the opening of ‘where it hurts in life’.

4

Most surprisingly to me, was the way Brossard manages to cut away all the sinew and yet still leave such seductive, non-clichéd sentiments. In ‘Reverse/Drift’ she write ‘so that the beast becomes enamoured / of strangeness and lifts its claws / to your neck’. Sex and violence all in one! Becoming ‘enamoured / of strangeness’! How intoxicating! A ‘slow image of pleasure’ indeed.

5

In ‘A Rod for a Handsome Prince’, we find ‘her skin of orange and olive’ before finally arriving at

6

and so body to body in the tuft

her spreading out in vegetation

right to them

the point of consent and

affirmation

little magic boxes

7

Pound wrote that a poet should never write to bore or to confuse, and I don’t believe Brossard has that intention at all, leaving the sexual connotations blatantly apparent for all. Even more so is the final stanza,

8

A ROD FOR A HANDSOME PRINCE swells

(but)

since the grafts

gently the words run

along it quietly

9

This is as close to being overtly obvious as Brossard attempts. In the selections from Lovhers, she manages to go even deeper into this sensuality, with its

10

[… ] patience

of mouths devoting themselves to understanding

integral

body against thighs legato

only fever: the eye without its sighting

11

Of course the word ‘integral’ is left by itself, connecting the mouth to the body, because it is that important.

12

The last 41 pages are made up of essays and an interview. While enlightening, due to Brossard’s views on why she writes in French and her strong beliefs in Feminism and its connection to poetry, the most interesting is actually the 21-page introduction by Jennifer Moxley. Moxley claims that Brossard’s poetry ‘reunites the aesthetic and the political’, which becomes more and more apparent the further one delves into Brossard’s work.

13

Moxley also speaks at length of the translator’s job, having translated some of the selections herself. Because the double meaning of some words gets lost in English (langue meaning both the physical tongue and language itself) it does add to the respect for the poets doing the translations that the poems rarely feel as if they are translations.

14

In places, Brossard is reminiscent of Rae Armatrout, in others of Lorine Niedecker, and comes off as someone Ron Silliman would love, yet she is definitely her own species, Quebecois or otherwise. It’s good to see the University of California press doing such a fine job in bringing out books like Brossard’s, which definitely deserves a readership in the English-speaking world.

John Findura

John Findura holds an MFA from The New School. A Pushcart Prize nominee, he is the author of the chapbook Useful Shrapnel (Scantily Clad Press) and his poetry and criticism appear in journals such as Redivider, Fourteen Hills, Verse, Fugue, No Tell Motel, H_NGM_N, Copper Nickel and Rain Taxi, among others. Born in Paterson, he lives in Northern New Jersey with his wife and daughter.