| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Mary Kasimor and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-boyer-rb-kasimor.shtml

Anne Boyer

The Romance of Happy Workers

reviewed by

Mary Kasimor

Coffee House Press, 2009, 978–1-56689–214-8 US$16.00 90 pages

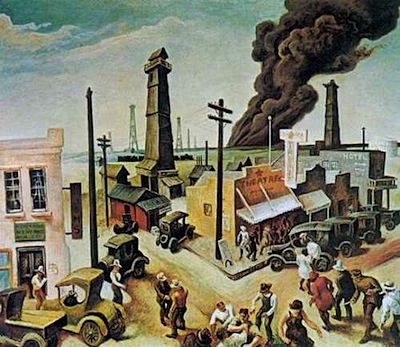

Thomas Hart Benton: Boomtown, 1928

1

Anne Boyer revels in the layers, the history, and the edges of her flamboyant love for, and skill with the English language in her book, The Romance of Happy Workers. Through playfulness, Boyer gives the readers meaning in and behind her poetry. The Midwest is a geographical and sociological phenomenon where change is slow, whether it is cultural or social change. There is a certain resistance to new ideas; this is also true with poetry. Boyer is an exception. Her poetry is filled with a reckless attention, giving the reader a new look at language, and still paying her dues to the old masters.

2

The title, The Romance of Happy Workers, evokes images of a bucolic setting with happy blue collar workers — working in harmony with something larger and more important than their daily wages and routines. However, Boyer shows us a comical version of disharmony and romance, rather than the idealized harmony of nature as expressed by the Romantic poets. Boyer’s version is that of the workers providing romance, rather than nature, and she seems to be working within the geography of her location: the Midwest, specifically Kansas. The Midwest covers a great deal of land, and there is a peculiar and similar feeling to this land in the middle of everything. Those of us who live in the Midwest take a certain stubborn pride in the hardships of inhabiting this part of America. People live with great beauty, but much of that beauty has an austerity (and anxiety) to it, and those who live there have to live close to the hardships of the natural world in this place. Besides the huge geographical area it is an area without many large populations. Boyer expresses that with an attitude and quirkiness, writing with tones of loneliness, isolation, too much life on the prairies and plains, too much small talk, and daily desperation so that it sounds interesting, exciting, and yet desperate.

3

The Romance of Happy Workers is divided into several sections. The first section is a comical series of poems that reference Woody Guthrie, socialism, and socialism’s various ideological offshoots. It is often unclear where the poems are taking the readers; Boyer does not seem to want to leave us with a clear political/social message. She does not include a variation on the harsh reality of communism under Lenin and Stalin. Instead she seems to be playing with the ideas to give us images and possibilities of communism and community. Rather than being left with a strong message, she takes us down into Alice’s rabbit hole and turns the playfulness into itself. Boyer tells us that “His lips {Woody’s} were a proletarian mediation/on May, a battle between pathogens.” She begin with a strong image of socialism, including the importance of May, especially the annual communist May Day, but then Boyer switches to a fight between germs. Is she reducing this ideological battle to a battle of germs?

.pp

Presenting Woody Guthrie as the hero, or the anti-hero of the movement is brilliant. Woody Guthrie evokes all the best attributes of the American socialist/people’s movement. However, Boyer gives us a flawed, somewhat frustrated, and comical version of our American hero — or my American hero. More lines from Boyer’s poems illustrate Woody’s thoughts on capitalism. combing the political and the personal:

4

Sometimes Woody eyes me

Over his unhappy salad and speaks

Of statistical probability.

We are like capitalists searching for paper clips.

5

At times, I think that Boyer is giving the reader the folk art revision of the revolution tongue-in-cheek, the revolution that the artists were supposed to create

6

during that time in Russia:

Blatant as an industrialist,

These lies from the factory.

But how did art sound?

I’d say punchy, with action verbs

7

Boyer captures the ideas, images, and nuances of Russian communism that many of us are familiar with in a startling way, “Bolshevik mattress,” and “Kremlin of lips,” juxtaposed with images of the western world, such as “Hamlet’s kiss,” and “Tyroleans mouthing Viennese rock songs,” and Woody is the hero who keeps — or tries to keep it all going — singing, working, producing… . Communism was and still is a serious subject; however, Boyer has made all the implications of communism serious and light-hearted, offering them up to us to examine under many different lenses, and then to examine again. She uses Woody as the conduit for approaching communism with American idealism, and my understanding of the history of communism in the United States is that it was an idealistic mythos, rather than the grim reality of Russian and Chinese communism.

8

Throughout the book Boyer shows us her ability to take language apart and to put it back together into new meaning in her new/old country. In the next section, she shows readers the cowboy ethos, once again using names and mythology with the stoic but reckless nature of the Midwestern prairies and plains dwellers. Boyer turns the American mythology into concrete language that still leaves the reader struggling for her own words to describe what Boyer is describing, moving beyond the cliché of what is the expected in the poem, “Biplane: In a plain democracy blue skies are axes, axes are soap,/Perseus is a stuttering tendency. Medusa is a sod ear,/and the corral shudders with ponies: winged things.” In her poem, “Larks,” Boyer continues to take the reader on her prairies/plains journey: “do not hope for a minute I would not turret, moat and knight for you. I would Harvester and John Deere and Pioneer for you.”

9

Throughout the rest of the book, Boyer takes us on a romp, a revelation, and a rowdy journey, even a polka and waltz of the world and its language. She offers the reader the plain language of the plains and prairies with insights into what people know, but have known through different cultures and words. She uses the common and everyday to express the mystical revelations of an ordinary life; however, what she is really telling me is that there is nothing ordinary, or it is sublime in its ordinary nature — and that is the secret of these homely places. In her poems the obvious becomes an awareness that we live in unaware ways. Several of Boyer’s lines reflect this in the poem, “GRIP:” “People who think in lonely sentences are lonely./Beasts who think in lonely sentences are beasts.” I am trying to paraphrase what Boyer expresses in this book of poetry, that beside her glittering and sardonic wit is that the obvious is often too available for us to see; we need the Buddhist bonk on the head to help us identity what we have walked over without noticing.

10

Finally, Boyer uses the language of Lewis Carroll by creating new meanings for our words. With these line, “The cricketry thought/from the bray and the haw,” I understand what she is saying through the intuitive sound of language, with the denotative meaning of the words giving me the clues to what she may mean — or not mean. Another example of this if found in “Elegy,” in the lines, “The human thought a blouse/waist and south thought Adam.” Finally, in “Oh Universe!” Boyer writes (and reveals), “Twittering Atlas triggered/his handgun.”

11

Even though Boyer gives a location for her poems, I realize that where the poet fits geographically is a part of the poetry, but only a part of it. Location fits into the words and words fit into the location, thus resulting in a unique placement of the meaning of location. Because of location, Boyer’s language has immediacy to it. In areas where the natural world functions with the world of human beings, the human made materials are functional, reminiscent of William Carlos Williams’ first few lines from his famous poem, “The Red Wheelbarrow.” In a geography of open spaces, human existence does depend upon the word. I have often wondered if my placement (or life) in a small Midwestern city has thwarted my own freedom with language; there is something to be said about enlarging language experiences by being enveloped in the culture of people, rather than the culture of geographical spaces. Boyer seems to be able to embrace the vaster uses of language without sacrificing her feel for the land, people, and culture — somewhat and sometimes uninhabited.

Mary Kasimor

Mary Kasimor teaches writing and literature courses at a technical/community college in Minnesota. Her passion is poetry. Her poetry has been published in many online and print journals. Her book of poetry, silk string arias, was published by BlazeVox Books, and she has another book of poetry, & cruel red, that will be published by Otoliths and available sometime in early 2010.