| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 7 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Noëlle Janaczewska and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-arcade-rb-janaczewska.shtml

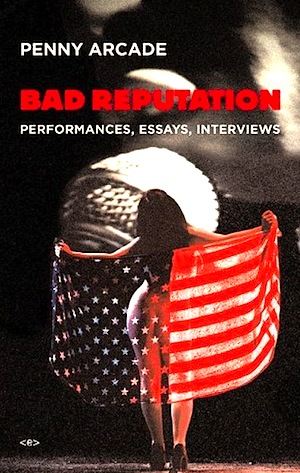

Penny Arcade

Bad Reputation: Performance, Essays, Interviews

reviewed by

Noëlle Janaczewska

196 pp. Semiotext(e) Native Agents Series. Hardback. USD$19.95. 978–1-58435–069-9 cloth

1

As far as I know, there exists only one photograph of my mother’s mother as a young woman, and my parents’ wedding was recorded in half-a-dozen black and whites. By contrast, my brother’s nuptials were filmed in moving colour — many hours of moving colour, in fact. Until recently, as Viktor Mayer-Schönberger reminds us:

2

Remembering was hard and costly, and humans had to choose deliberately what to remember. The default was to forget. In the digital age … that balance of remembering and forgetting has become inverted.

3

It may sound paradoxical, but storytelling and theatre, along with rhymes, mantras, songs, stone-carving and painting, helped us remember, by allowing us to forget. I saw Penny Arcade’s Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore! when it played Sydney (Australia) in 1995. I remember clearly its audacity and campy irreverence, and the jolt of a line about prostitutes being an essentially conservative group of women. The details have since faded into the bigger picture of artistic themes that characterised the late 1980s and1990s.

4

The three scripts in Penny Arcade’s Bad Reputation, a collection of performance texts, essays and interviews, belong to that decade. But unlike many staged self-portraits of the era, Penny Arcade tackled the politics of identity politics head on. She’s got ire and punch aplenty, but also bucket-loads of compassion and humour, and she’ll denounce censorship and prejudice no matter what direction it comes from:

5

This narrow-minded thinking, it’s not just coming from the Right Wing. No, it’s coming from the Left Wing, too. Of course it is. What about the politically correct movement? The politically correct movement has a stranglehold on this country. (102)

6

As someone or other once said: there are times when the personal is political is not political enough.

7

But first, a bit more about this remembering and forgetting business.

8

Film remembers whether its images are collected digitally or on celluloid; a concert can be captured on CD or for download to an iPod. Theatre, dance and stand-up however, are ephemeral, and you have to be there for the duration. (Yes, you can watch a DVD, but it’s an altogether different experience.) This poses a dilemma for performing artists, not only because the whole arts programming and funding shebang requires documentation, but also because it is a very human story to ensure we haven’t lived in vain, to want to say: I was there, I did that — here’s the evidence. Be it a wedding portrait, home videos, or a published script.

Penny Arcade

9

First the essays and interviews. These are a mixed bunch, but the writers are united in their belief that Penny Arcade has received neither the critical attention nor the recognition she deserves. A point-of-view shared by Penny Arcade herself in a meandering interview with Chris Kraus.

10

Perhaps this is my English-Australian sensibility, but some of these contributions are just a bit too self-referential for my taste. Important questions circle in a maelstrom of names, venues and events; interesting ideas get lost in the gush. The tensions between performance art and theatre, for instance, between work that derives from the visual arts and that which springs from the alternative or underground performance scene. On the plus side however, you do get a glimpse into the New York arts world of the late twentieth century from those who were there.

11

For those of us who weren’t, Stephen Bottoms’ essay provides useful background and context. As does Sarah Schulman’s elegant and succinct introduction to La Miseria.

12

And so to the scripts. Over the course of a long career, Penny Arcade has produced an impressive body of work. The three scripts selected for this book make up a thematically linked trilogy. They circumnavigate similar territory and revolve around Penny Arcade herself, or rather the persona that is Penny Arcade.

13

Most significant artists tend to return, obsessively, to mine their core material from different angles. (184)

14

La Miseria, written in 1991, is the most play-like of the three. A portrait of her working-class Italian-American family set during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. High energy inter-generational conflict is played out across the kitchen table and before the stained glass windows of the Catholic church. In common with much theatre about the migrant experience, La Miseria is bilingual, features a conservative parent, an intransigent religious establishment, and a rebellious offspring desperate to escape the family mould. Tonally, it is a blend of melancholy and the grotesque, with considerably more of the latter.

15

Sarah Schulman, who also transcribed and edited the play for publication, says in her introduction, that Penny Arcade’s achievement was to marry the pushy politics of performance art with the emotional pull of theatrical realism. Like many marriages, it has a few problems …

16

With Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore! (1990) and Bad Reputation (1999) Penny Arcade moved away from the constraints of narrative drama. While she continued her translation of personal experience and polemic, it was now into her own brand of public performance language. Drawing on European burlesque and agitprop cabaret as well as what I think of as the ‘American confessional’ tradition.

17

Bad Reputation is her tumultuous coming-of-age tale. It is about being a bad girl, and being labelled a ‘bad girl’. About how society polices the boundaries of gender and desire; the myriad ways it seeks to confine and control those it deems transgressors. About the highs and lows of life on the fringe. In terms of subject matter, it is a rough-tough ride of a script, bouncing around a landscape of rejection and rape. The emotional text is sharply-focused and turns largely on hurt and anger, sometimes raw, sometimes darkly comic. The writing is textured and varied, moving from monologue to zigzag poetry, from documentary re-enactment to an almost choral score.

18

Penny Arcade is on a mission to expose hypocrisy. She zeroes in on those areas where society has double standards, where the real values of a culture play themselves out. Gamble on the stock market and you’re a winner — even if you’re not; bet at the racetrack and you’re a loser. Racist vitriol pours from the mouths of those who are themselves first generation immigrants. For girls, virginity is a precious gift to save for Mr Right, for boys it’s something to get rid of a.s.a.p.

19

Realism and how she bends it, crops up regularly in discussions of Penny Arcade’s oeuvre. There is indeed an intense, ethno/graphic quality to her observations and in much of the writing, but it’s more Margaret-Mead-on-speed than kitchen sink. Whether she’s dissecting her relationship with her mother, riffing on the history of Barbie or exploring the delights and dead-ends of being a female bohemian. (There are a couple of tantalising references to a more recent work, New York Values, an Autopsy on the Death of Bohemia. Wish I could be there for that one.)

Of the three scripts in this book, Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore! is my runaway favourite. It has all Penny Arcade’s hallmark wit and candour, but with less of the Catholic crap. This time we meet Charlene and the Phone Girl as well as Penny, and those other characters (both played by Penny Arcade) are given space and dramatic weight within the piece. Here the autobiographical revelations are counterpointed by a questing, essayistic voice, and the resulting mix of anecdote and analysis is a powerful one.

To describe Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore! as a series of monologues punctuated by dance routines — which is what it is on paper — fails to convey its impact as theatre. Its energy and sexiness, its intelligence and sheer gutsy originality. You had to be there. Not least to see those erotic dancers strut their stuff. That’s the trouble when you have only the written text of a performance: it’s like trying to put together a jigsaw, when half the pieces are missing.

20

What I do when I’m developing a piece is improvise, improvise, improvise … But I also taped everything. (20)

21

These weren’t scripts dreamt up and written by a playwright sitting alone at their keyboard. They were developed in increments and through improvisation, refined by lengthy processes of try-out and revision, and by the input of collaborators.

22

So saying, a great deal of thought and care has gone into preparing the scripts for publication. Settings, costumes, gestures and movement have been described and inserted at appropriate places in the spoken text. And more than that, more than simply the nuts and bolts of stage business, Sarah Wang, the editor and transcriber of Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore! and Bad Reputation has created stage directions that try to give the reader a sense of what it was like to be there, in the audience. Directions which don’t so much detail the visual and choreographic texts as weave their own fascinating meta commentary. Here are a couple of examples from Bad Reputation:

23

Laughter from the audience. Penny fills the room with her stories, spinning them outward and pulling them in again. We are the rapt listeners to her Scheherazade … She’s telling us a story, writing her story, navigating through the personal the political. (135)

24

And:

25

We want to nod, to scream out “YES,” — run onto the stage and embrace Penny, assure her of our loyalty, promise her that we would never hurt her. But somewhere inside, we know that we have been that girl, one of those girls who ran out on Penny, left her in the madness of the moment to defend herself against rapists, murderers, pedophiles. We are implicated. We have played this part. (162)

26

Nevertheless something is lost in translation from stage to page. Actually quite a lot is lost. A script is not a performance, and no matter how many pieces of unspoken, stage business are added, it can only ever amount to half the jigsaw. Which begs the question: why publish a partial account? Why not go with the transient nature of your artform? In an age of cloud computing and unlimited data storage, when Google probably knows more about us than we can recall ourselves, when it seems everything is remembered and nothing truly erased or forgotten, why not take a radical step and eschew documentation?

27

I doubt my brother will ever sit down in front of his laptop or TV and watch all those hours of wedding footage. There’s so much of it, he couldn’t possibly remember what was recorded on those discs. Of my parents’ wedding photos, two are on display in my mother’s house, while the remaining four sit between layers of tissue paper in a top drawer, readily to hand for my mother to explain who’s who and what’s what in each of them. But this remembering and forgetting equation is massively more complex than analogue versus digital, or less is more. After all, the availability of home scanners and cheap photographic printers, not to mention PhotoShop, has meant that everyone in our extended family now has their own copy of that sole snapshot of my grandmother aged twenty-four.

28

I suspect playwrights and performance artists often become fixed on publication because in our culture, the book, the printed word, carries an authority live art can’t match. That is, it used to. In our digital world, all that is up for grabs. So although a part of me wants to urge artists working in theatre and performance to resist the tyranny of documentation and embrace the fleeting, in-the-momentness of their art, another part of me understands the impulse to record and memorialise in print. Sort of.

29

Here’s Viktor Mayer-Schönberger again:

30

Forgetting performs an important function in human decision-making. It permits us to generalize and abstract from individual experiences. It enables us to accept that humans, like all life, change over time. It thus anchors us to the present, rather than keeping us tethered permanently to an ever more irrelevant past. Plus, forgetting empowers societies … to remain open to change.

31

But all that has got nothing to do with Penny Arcade, who — quite rightly — wants her place in history. Wants her work made accessible to those who weren’t there, and accorded the critical scrutiny that is its due. She doesn’t want to be forgotten. Why? Because, as Andrew Frost reminds us in his review of Circa 1979: Signal to Noise, a conference celebrating Sydney’s post-punk era of music and image-making:

32

One startling rewriting of the post-punk era was the absence of any women on the panel. The great heritage of the feminist movement in the late ’70s was a consciousness that gender divisions were over in the creative arts … women were at the forefront of the creation of art. You’d never have known it from the dreary day at the Seymour Centre.

33

Because women are always forgotten.

Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor. Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009. 196–7.

Frost, Andrew. Cultural ganglands alive and kicking. The Sydney Morning Herald. January 29, 2010. February 7, 2010. < http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/cultural-ganglands-alive-and-kicking-20100128-n1lq.html

Noëlle Janaczewska

Noëlle Janaczewska is Sydney-based multi-award winning writer of plays, performance texts, libretti, monologues, spoken word, poetry, essays, gallery and on-line explorations, and radio scripts across drama and non-fiction. Her work has been performed, broadcast and published throughout Australia and overseas. Recent works include: Dark Paradise, There’s Something About Eels … and Pitch Black for ABC Radio National, Eyewitness Blues for the BBC, The Hannah First Collection, 1919 — 1949 for the Zendai Museum of Modern Art in Shanghai, and Dorothy Lamour’s Life as a Phrasebook, published by Wayzgoose Press in 2006. Find out more at http://outlier-nj.blogspot.com and www.noellejanaczewska.com.