| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 3 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Santos Perez and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-aragon-rb-perez.shtml

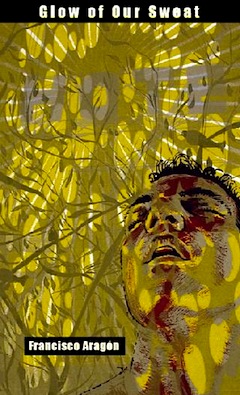

Francisco Aragón

Glow of our Sweat

Scapegoat Press, 2010 72 pp. 12.95. ISBN: 978–0-9791291–3-1.

reviewed by

Craig Santos Perez

1

Francisco Aragón’s Glow of our Sweat (Scapegoat Press, 2010) explores the themes of sexuality, geography, memory, and translation. Interestingly, Aragón brings together original lyric poems, translations, experimental translations, and a nonfiction prose essay. In an “Author ’s Note,” Aragón describes his assemblage as “poetry in conversation with prose” that aspires to be a community where multiple voices “mingle, converse, commiserate.”

2

Glow of Our Sweat includes homage poems to Jack Spicer, Rilke, and Whitman. Through these poets, Aragón captures a variety of listening: listening to the outside to learn something about the self (Spicer); listening to the rumble and bustle of human experience (Whitman); listening to the deepest, angelic core of the object (Rilke). At one point, Aragón re-articulates Rilke’s “Torso” with a poem that ends: “Step closer: // go blind.”

3

In addition to honoring his poetic influences, Aragón intersperses translations of Federico García Lorca, Rubén Darío, and Francisco X. Alarcón. Some of these translations are “faithful” to the original, while others “riff” off the Spanish originals, which are included in an appendix. The inclusion of these translations is another way to pay homage to one’s influences. Additionally, the themes of the translations actually accentuate the narrative and emotional arc of the original poems. Perhaps Aragón is suggesting that poetry itself is a way to translate experience and memory. A resonating line is from Lorca’s “The Poet Speaks with His Beloved on the Telephone,” which ends: “Faraway, sweet: lodged in the marrow!” (Aragón’s translation, 16).

4

In his original poems, Aragón focuses on what is faraway and sweet, yet lodged in deep memory. The poems move through various cities: Madrid, Dublin, Vatican City, Berkeley, New York City, and San Francisco. One of my favorite poems, however, is one where any city feels faraway:

5

“Earplugs”

Putty globes

thumbs press

into place;

drifting to sleep

beside you

for the first time,

trying to: your

seemingly distant

muffled snore

more than heard

— felt, at intervals;

and in between:

interior sound

of my breathing,

my heart. (26)

6

Many of the original poems examine interpersonal relationships, some that are sweet and others that are heartbreaking. In “San Francisco, 1985,” Aragón describes a scene in the Castro — the gay neighborhood in San Francisco. The speaker is riding the bus when two friends spot him and board the bus. The speaker casually asks one of his friends: “How are you feeling?” The poem ends:

7

You grin touching my sleeve.

So it’s this. This is what stays,

what sticks to me. He left us

sooner than expected:

I never made it to Alta Bates.

Afraid, perhaps, I’d undo

a ride on MUNI one

December afternoon. (34)

8

This is a subtle poem about AIDS, about how we remember amidst tragedy. The speaker holds on to the small gestures that remain, as opposed to the decaying and death of a friend. Throughout, the poems capture a poignant sense of nostalgia without being overwrought with sentimentality.

Francisco Aragón

9

Glow of Our Sweat ends with an 11-page nonfiction prose essay titled “Flyer, Closet, Poem.” The essay begins with the speaker running “Bridge to Bridge,” a race covering eight miles along San Francisco’s waterfront. Besides a source of strength, running also becomes a metaphor for how the speaker is changing and crossing life’s bridges. Composed of short vignettes, the essay then moves to the speaker’s first year of graduate school, when he is invited to read at a pride event. His classmate asks if she could announce the reading in their creative writing class. The tension: the speaker isn’t yet “out of the closet.”

10

Despite the speaker’s academic and athletic success, he feels a deep dread: “I’d rather be dead than have anyone, friend or stranger, learn my secret” (48). Aragón draws our attention to the idea of “covering,” referring to Kenji Yoshino book Covering: The Hidden Assault on our Civil Rights (2006). Within the space of the essay, Aragón asserts: “I feel as if I can no longer remain quiet about who I am.” By coming out, the speaker feels that poetry becomes a way to uncover.

11

The essay ends by describing an anecdote about the intersection between poetry and sexuality. Aragón tells the story of a young, gay African American poet who falls in love with a sonnet by a famous African American poet. The young poet recites the poem on camera for a popular national initiative that allows different people to recite and discuss a favorite poem. After the heirs of the famous poet view the recitation, they withdrew permission to disseminate the video and use the sonnet. Aragón suggests that this gesture proclaims to gay poets: “We do not approve of who you are, what you are” (52).

12

The poems, translations, and prose in Glow of Our Sweat continue the speaker’s personal and aesthetic uncovering. Aragón journeys from poem to poem — bridge to bridge — to celebrate who and what he is — denouncing anyone who would disapprove. Aragón weaves multiple voices, geographies, temporalities, genres, and languages to translate and tell the story of his uncovering. Within this story, Aragón focuses our attention on “the remains / of a moment: / glow of our sweat” (42).

Craig Santos Perez

Craig Santos Perez is the author of from unincorporated territory [hacha] (Tinfish, 2008) and from unincorporated territory [saina] (Omnidawn, 2010).