| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 23 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Marcia Casey and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/casey-the-human.shtml

Readers wanting a different angle on Heidegger and his vexed and intimate relation to the cult of Nazism should consult Anthony Stephens’ article “Cutting Poets to Size – Heidegger, Hölderlin, Rilke” in Jacket 32:

http://jacketmagazine.com/32/stephens-heidegger.shtml

1

Being human is an art. We are born to it, and yet somehow it requires our highest and best effort. As Darwin, speaking of our distinguishing feature, language, put it, we humans have “an instinctive tendency to acquire an art.” [1] I believe the same can be said of our lives — beyond mere survival and reproduction, we are drawn to making sense of the world and, further, to acting in accordance with what we understand, to creating a work of art — a life that has meaning — in that context. And written language, literature, is in some way the distilled essence and record of this messy business, our living in the world and our endless daily dialogues about the ongoing process of finding and making our individual and communal human way. According to Robert Finch and John Elder, editors of The Norton Book of Nature Writing, “All literature, by illuminating the full nature of human existence, asks a single question: how shall we live?” [2]

2

It is a question about self and context, about what is true within and without, about right relationship and right action. It is a question about both what makes us human in the first place and how we stay human now, moment by moment, in our individual lives, in our historical time. It is a question that implies art, an instinct whose hunch is that there is a rightness in understanding, in speaking, in writing, in making an object, in making a life, that can be sought and discerned and perhaps sometimes attained.

3

It is this urge toward art, applied to the nature and path of being human, that is the origin and aim of this essay. I am seeking some rightness, something that feels true, in my own thinking and writing, and in the thinking and writing of others, about who we are and how language takes part in this. Like Finch and Elder, I look to literature to inform my understanding of human being and how we shall live. This most fundamental human question was addressed by every author I’ve read in the last year, in artful ways that ranged from the intimate to the abstract, and I’ve called them, by name and initial, into a discourse. In this critique, by seeking, sifting, selecting and ordering what these authors say about being human, and by my own thinking-with them and writing-with them in pursuit of understanding our gist, I aim to get a glimpse of the human in action, to see the outline of the human dilemma of our time, and perhaps to gain some insight on how, right now, we shall — most rightly, most humanely, through language — live.

4

The creation in the first place,

being itself, is the only necessity.

— Annie Dillard

5

There is only one place to begin — here, now, with this, what came into being with “the lone ping of the first hydrogen atom ex nihilo,” (AD) [3] matter. Matter, mater, mother earth, mud. Substance, “the first knot, beginning of the spiral: / life and death, birth and rebirth.” (CV) [4] With matter, the specific is born, each entity, the actual. Our actual one and only earth is born and reborn of accumulating, mutating matter as, generation upon generation, the spiral of evolution churns out lava, algae, egrets, oaks… all of nature, our realm.

6

Heidegger tells us that the poet Rilke “calls nature the Urgrund, the pristine ground… of those beings which we ourselves are” [5] — nature is both source and all-encompassing arena of human enactment, that in which we are utterly grounded. Emerson brings it closer, makes it personal; he says, “We come to our own and make friends with matter… we can never part with it; the mind loves its old house… We nestle in nature and draw our living as parasites from her roots and grains.” [6] This sustaining nest of “sensuous fact” (RWE) [7] is home to the human, is the human — abuzz with frenetic atoms, matter echoes up from our bones, from our brains, “from the speechless invisible world swarming in the unconscious depths of individual consciousness.” (JR&SM) [8] And set in the midst of “the senseless world swarming outside the individual ego,” (JR&SM) [9] we find matter gathered around us as roots, grains, caves, glens, the geography of our world. Matter spun into nature is what we are, where we are, what we know.

7

We humans perch — here, now — seeing inward and out, seeing each and all, parts and whole, beings and Being, in matter and its concatenations. Everything is implicit in its explicit fact. One fact and all. That “lone ping,” Dillard says, in and of itself “was so unthinkably, violently radical, that surely it ought to have been enough, more than enough. But look what happens. You open the door and all heaven and hell break loose.” [10]

8

All truth is the transference of power.

— Ernst Fenellosa

9

Beginning blew the door off the jamb of that moment, that eternity of stasis in which Being and Nothing were hidden — Matter began! That “ping” tipped the balance, pushed us over the edge, set the clock running. To begin is to break with the past, to draw a line and to cross it. The first line, the number one. To begin is to coalesce, to become one, to step over the line made into a circle, into oneself, into being — by gravity, a drawing toward the center, the force of coherence, the power that conjured matter out of no air, nowhere, tipped nothing toward becoming something. The force with which one hydrogen atom coalesced (ping!) into being and left the Void behind. Became/Began. “The world functions because from the outset there is a lack of balance,” [11] Epicurus thought. The outset, the beginning: Gravity (the original imbalance, a force, the tilt toward becoming) plus Matter (the precipitate, what’s mesmerized into fact, into being, coherence incarnate). Force and substance coeval: two aspects, one entity: “the first knot.”

10

The tied knot, the wedding kiss of gravity and matter, fluidity and fixity, impulse and stillness: to draw a line and simultaneously to cross it. To become one is to become two, self and not-self — and the gravity that drew the first line into one, arcs between the implicit two, drawing them together toward a mutual center, breaching that line, “the rift… that… joins,” (MH) [12] setting into motion “the course of the history of Being.” (MH) [13] Suddenly “reality is not substance, solidly and stolidly each in its own place; but in events, activity; activity which crosses the boundary.” (NOB) [14] Matter, each body, each entity tenuously coalesced, is held yet again in fluid liaison with every other body, by the activity of gravity, that force inherent in matter by which “each particle of matter attracts every other particle.” (IN) [15] “An object is not an object, it is the witness to a relationship,” [16] the world come alive, responsive, says Cecilia Vicuña. The truth of the whole lies not only in the internal arc of each coalesced entity, but in “inclination and precipitous attraction,” (JR&SM) [17] pull and jostle and cataclysm between them:

11

A true noun, an isolated thing, does not exist in nature… Neither can a pure verb, an abstract motion, be possible in nature… The truth is that acts are successive, even continuous; one causes or passes into another… All processes in nature are interrelated; and thus there could be no complete sentence… save one which it would take all time to produce. (JR&SM) [18]

12

All time, “the course of the history of Being”: Gravity (attraction, the force toward coherence) compels embodiment, requires the specific, precipitates Matter — and yet, brimming ever unabated, compels as well the dissolution of its very creations, seeking still greater coherence. The tied knot, first weaving, then “unraveling in the air, begins again.” (CV) [19] Gravity mesmerizes matter into being, yet every incarnation is merely a

13

crust… that will easily rip

as soon as the energy inside outgrows

(it) and seeks new limits. (RMR) [20]

14

Gravity, perpetually weaving matter, its skin, into being — into beings — as well perpetually sheds it in death, moving on and on through them, “successive” and “continuous,” in its inscrutable pursuit, coherence. Inherent contradiction, spring of the spiral careening onward from integration to dissolution to a wider integration to a new dissolution… each beginning an end, each end a beginning, endlessly.

15

To become one is to imply other; in fact, to imply all. To constellate one is to constellate the whole, “all heaven and hell,” beginning and ending, endlessly becoming, in a “successive” and “continuous” upwelling of coherent beings evolving in themselves while relating, shifting, merging into and emerging out of each other in a field of gravity that groans with attractions from atoms to planets, each entity also groaning within with an urge toward greater coherence. Matter and Gravity wed — hotbed, marriage bed, seedbed seething — the Ground, Urgrund, “the medium that holds one being to another in mediation and gathers everything in the play of the venture,” (MH) [21] Existence.

16

Look up! Look up! O citizen of London,

enlarge thy countenance…

— William Blake

17

We each begin here — beings of earth, mortal humans — with matter drawn close around us. We find ourselves at home in the nearness of things. We stroll the neighborhood, look around — we want to see what we see. “What you see is what you get,” [22] Annie Dillard advises us. We keep looking, scanning, searching — what do we get? Homegrown, we state the obvious, say what we see, tell “who did what to whom,” (SP) [23] the explicit. We “name the thing because we see it… This expression or naming is… a second nature, grown out of the first, as a leaf out of a tree.” (RWE) [24] We creatures of earth squawk and howl and chatter, speak of our earthy home with earthy words; we get this.

18

But then we raise our eyes a notch and gasp: “In every landscape, the point of astonishment is the meeting of the sky and the earth.” (RWE) [25] It moves us, holds us, gets to us in some way we don’t quite understand; it’s hard to say what it is. Something opens in us, we need something — we “go out daily and nightly to feed the eyes on the horizon and require so much scope.” (RWE) [26] Scope! The far enters that opened place in us, and the near marvels. Near and far echo and echo in there, growing richer and deeper, until at last we dare to lift our eyes full up, to the final farness, face to face with the sky. It takes our breath away:

19

The radiance of its height is itself the darkness of its all-sheltering breadth. The blue of the sky’s lovely blueness is the color of depth. The radiance of the sky is the dawn and dusk of the twilight, which shelters everything that can be proclaimed. (MH) [27]

20

We peer into the sky and reel at impossible brilliance, impossible darkness, impossible depth, impossible beauty, the impossibly far… Speechless, we cannot get what we see, yet, mesmerized, we cannot leave it:

21

Into… everything that shimmers and blooms in the sky and thus under the sky and thus on earth, everything that sounds and is fragrant, rises and comes — but also everything that goes and stumbles, moans and falls silent, pales and darkens… the unknown imparts (it)self. (MH) [28]

Thus the unknown… appears… by way of the sky’s manifestness. (MH) [29]

22

Agape, we stare; we see the sky’s matter, a continuous billowing of light and air, but in it, of it, behind it is something far off we cannot see or say, yet profoundly sense:

23

I could see that there was a kind of distance lighted

behind the face of that time in its very days

as they appeared to me but I could not think of any

words that spoke of it truly nor point to anything

except what was there at the moment it was beginning

to be gone and certainly it could not have been proven

nor held however I might reach toward it… (WSM) [30]

24

As we reach out toward it, we reach into ourselves, in that deepening opening, where infinite farness and bottomless nearness shimmer together.

25

Silence is the mother tongue.

— Norman O. Brown

26

Naked, finite, mortal, we stand under the infinite sky, every pore and hair and sense sprung open, listening, looking, plumbing the deepness, feeling the arc of gravity across the abyss. Every instinct begs us, like wolves in the darkness reading wind and whiff and prickle, to attend, to try to discern what it means for us who sense it. Electric, alive, “witness to a relationship” unseen, we each stand open to enormity. We wait, “letting happen… the advent of the truth of what is” (MH) [31] — in us, on earth, out there, in the span between. We “wait for it, empty-handed,” (AD) [32] in an attitude that is “at once receptiveness and total concentration.” (AD) [33] Standing silent, before silence, our instinct is to find the truth of the whole of it, to get it right, to touch the essence of what we sense: one gesture or word or act to embrace it all, express it all, respond to it all, become it all. The silence thunders in us and, infinitesimal beneath the sky, we “stand there, balked and dumb, stuttering and stammering, hissed and hooted, stand and strive, until, at last, rage draw out of (us) that dream-power,” (RWE) [34] and gravity moves us, moves in us, in matter, with an unheard of alchemy, “the dangerous instant of transmutation,” (CV) [35] a new integration: the human. In that opening in us — the cauldron of consciousness of near and far — matter begins to speak in a new way:

27

Piercing earth and sky

the sign begins. (CV) [36]

28

Using every sense and muscle and nerve and earnest desire, mind and matter fused in communion with the sky, we choose what seems the rightest act or path; we move toward it, in accord with it, and

29

… being makes its offering to immensity. Two or three lines, a mark, and

silence begins to speak… (CV) [37]

30

In that place inside us, we follow our instinct to its final verge and, seeing beyond, burst free — “as a leaf out of a tree” rises on and bodies forth the arc of invisible wind, we begin to speak in a human tongue:

31

In the new

World, (we) say its name

tenderly, tell

its story — word

upon word, impossible,

inexorable,

coming to birth… (MC) [38]

32

It has taken me till now,

to be able to say

even this

it has taken me this long

to know what I cannot say

where it begins

like the names of the hungry

— W. S. Merwin

33

The new world: a new beginning — to make a break with the past, to draw a line and to cross it into unknown territory, into ourselves… and yet, “successive” and “continuous” with all of “the course of the history of Being,” never to leave what has gone before. To become human: still to “nestle in nature” — yet also, “piercing earth and sky,” to see beyond what’s in front of our noses and into the nature of things. To see and to say, nature and “second nature:” to see and to say both nature and nature of — sight and insight of world and earth in us become “the saying of world and earth… the saying of the unconcealedness of what is,” (MH) [39] the truth:

34

Language alone brings what is, as something that is, into the Open for the first time… Only this naming nominates beings to their being from out of their being. (MH) [40]

35

Earth and sky, world and word, matter and truth — coterminous, synonymous — join in us. Near and far become intimate, articulate — in us.

36

And yet this intimacy, this understanding, this eloquence, themselves cut us off from the rest of existence:

37

The union of self and cosmos given in the signifier can also be represented as rupture, fracture, schism, an eruptive signification: ‘The symbol originates in the split of existence, the confrontation and communication of an inner reality with an outer reality, whereby a meaning detaches itself from sheer existence.’ (JR&SM,AB) [41]

38

Something shifts in our vision, and with a sudden lurch, we’re no longer sure if we’re continuous with or “detache(d)… from… existence” — if we’re sheltered in or exiled from creation. And all our new-found significance, too, takes on an irresolvable uncertainty — is it immanent or detached, embodied or abstract, sight or insight, near or far, old or new, union or schism? Suddenly the world is fraught with dichotomy, opposites joined by the rift of their difference — like us, in us. We suffer from double vision and wonder if we reel from revelation or vertigo? We falter…

39

… and from our ecstasy we fall back to earth, grave and shaken, having pierced earth and sky, and having been pierced by a vision of beauty and terror, “grace tangled in a rapture with violence.” (AD) [42] With our double vision, we saw

40

that all things live by a generous power and dance to a mighty tune;… (yet also) that all things are scattered and hurled, that our every arabesque and grand jeté is a frantic variation on our one free fall. (AD) [43]

41

What was merely confusing suddenly turns sinister. The final dichotomy — life/death — dawns on us. We blanch with “rage and shock at the pain and death of individuals of (our) kind,” (AD) [44] of every kind, of our very selves. Horrified, bewildered, utterly changed, we look around at our fellow creatures, still unseeing, innocent in their unknowing, and suddenly,

42

… all

that’s here, vanishing so quickly, seems to need us

and strangely concerns us. Us, the first to vanish… (RMR) [45]

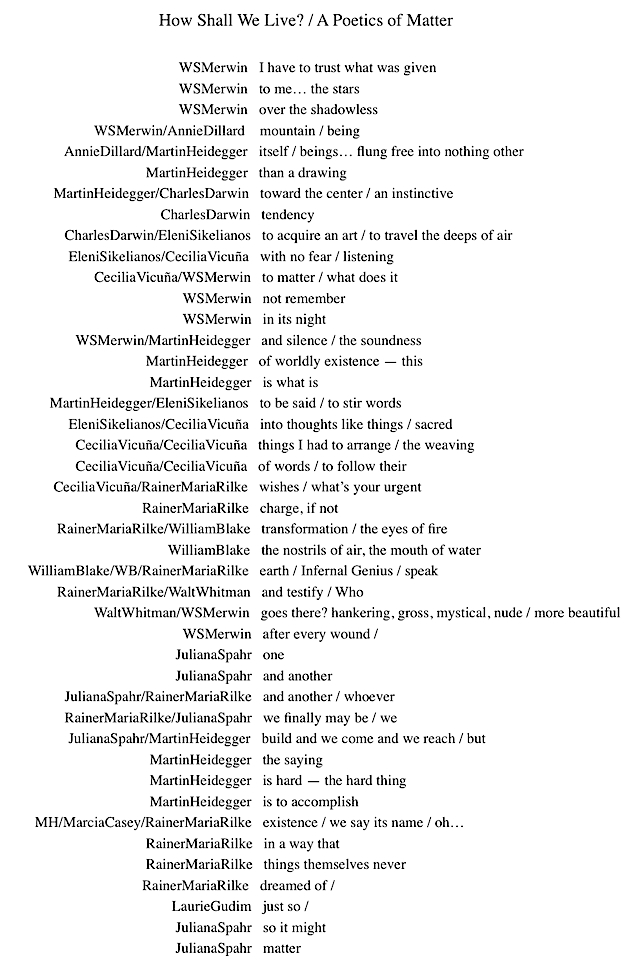

43

Terror, compassion, a terrible urgency seize us —

44

Ah, but what can we take across

into that other realm? Not the power to see we’ve learned

so slowly here, and nothing that’s happened here.

Nothing. And so, the pain… (RMR) [46]

45

Vulnerable and responsible, wholly alone in what we know, we long for our old earth, the bliss of our littermates, the simple vision of the near… even as we’re drawn ineluctably toward the trueness of the terrible truth. Every instinct urges us to make sense of the whole, but — “detache(d)… from… existence” through consciousness — we see that we could pull back our vision, set our point of focus just short of the whole, avert our human eyes, turn our human face away, decide not to see, pretend not to know, not to feel this pain. The ease of this falseness wheedles in us. We teeter on that cusp, and must choose: “The terms are clear: if you want to live, you have to die. This is what we know. The rest is gravy.” (AD) [47] We waver, wanting to know, wanting not to know, until at last, “There’s nothing to do about it, but ignore it, or see.” (AD) [48] In our hearts jangles a single question: “How shall we live?” And, in the midst of our pain, we must name our path — whole truth or half? integrity or deception? acuity or subterfuge?

46

Troubled, conflicted, the way unclear, impure — if we can, as we can, we each, born human, begin for the first time to be human: we choose, if we can, to continue to follow the trajectory along which instinct has brought us thus far, toward truth. We choose, as we can, to take the next step on this path, into the unknown, into ourselves, from instinct toward art: to consciously choose to try to be true to what we know — not only what we sense, unseen, quivering in the arc between earth and sky, but also the truths of our knowledge and our pain — to probe their depth, their poignancy, their power; to make something of them, in spite of death, in the face of death. To try to rightly see and say the whole truth, the one truth we know in our bones, our own:

47

… once each, only once. Once and no more. And us too,

once. Never again. But to have been once, even if only once,

to have been on earth just once — that’s irrevocable. (RMR) [49]

48

The impossible, the actual, the miracle: being. “Look, I’m alive! On what?” (RMR) [50] Gravity and matter, fluidity and fixity, coherence incarnate kissed to life, coalesced in us, this once.

49

We name this fragile being, each poignant instance of human being, even as it vanishes. We “say its name / tenderly,” give it one utterance, encompassing lineage and yet distinct, that’s irrevocably its own: “The token of the proper name spells out the seam or juncture… of language and the body,” (JR&SM) [51] of meaning and being. And “piercing earth and sky,” this sign, this token, this name, stands, immutable, where life meets death head on, eyes open — in us — and dares to state its irrevocable truth. In the human name of each human being, “the existence of something… ” becomes “… a sign and an affront to nothing,” (AD) [52] an invocation, incantation, conjuring, creating, sustaining meaning in even ephemeral being. Each alone, all together, we hover in that final rift, where life meets death, and utter each others’ beloved names, in the dark, out of the dark, “tenderly… ”

50

… until our perspective shifts and the vision vanishes. Severed from certainty yet again, we plummet back into doubt, fear, despair. We can never know, finally, if all meaning is gained or all meaning is lost. We wish so much for solid ground and clutch at nothing, suspended there, our endless question, empty center, still unanswered:

51

… is your answer

the question itself

surviving the asking

without end…

with nothing but its own

ignorance to go by (WSM) [53]

52

We don’t know, can’t know, the final answer; but moment by moment, day by day, we find

53

Our heart survives between

hammers, just as the tongue between

the teeth is still able to praise. (RMR) [54]

54

If we can, as we can, in those moments “between hammers,” we choose to try catch the sense of this shifting, swiveling, contradictory world —

55

And so we keep on going and try to realize it,

try to hold it in our simple hands, in

our overcrowded eyes, and in our speechless heart.

Try to become it… (RMR) [55]

56

to tell it, to live it — our truth. In our own name, we speak, we act — our lives and their meanings merge and blur, become words:

57

Gesture enfolds speech in a corporeal stance. (JR&SM) [56]

An object is speech because in being made it must reveal a person. (ML) [57]

Words are also actions, and actions are a kind of words. (RWE) [58]

58

We become human — the seeing, speaking, knowing, ignorant being — and great and terrible meanings quiver on our lips and dog our every step.

59

Our human voices quaver — in our human tongue, each vibrant word of the truth of the union of near and far is haunted now by a bottomless echo telling of our pain — how, “piercing earth,” we’re also cut off from the near; how, ecstatic “in communion with the sky,” (CV) [59] we’ll still never reach the ineffably far; how everything, everyone, is miraculously present yet will, in a flash, be gone — and of the quandary of our choice in the face of death; of our daring to be, regardless; and of our efforts to speak this, to live this elusive, mutable truth. Our every word names, in tone and undertone, tremolo and pitch and reverberation, the truth of what it means “to be here as we are,” (AD) [60] seeing both ways, knowing both grace and agony, luminous and dark. We cannot help but name in our language — nature and “second nature” — what it is to be us:

60

What is this naming? It calls into the word… calling brings closer what it calls… it brings the presence of what was previously uncalled into a nearness… But even so the call does not wrest what it calls away from the remoteness, in which it is kept by calling there. The calling calls… always here and there — here into presence, there into absence… (MH) [61]

61

Presence and absence — acute, infused — resonate in each word, reverberate in us. Each word, each step, is a struck bell, at once calling forth, and calling unendingly into, heartrending presence, unutterable emptiness. In us, the irreconcilable grow intimate; and summoning, plumbing, the indescribable “pain (of) the(ir) dif-ference,” (MH) [62] we humans, our language, as “threshold bear… the between.” (MH) [63] Our task is the impossible — to hold them both, irreconcilable, simultaneous. And our living, our speaking, at the threshold, in extremis, bear both the need to find a way to convey, in excruciating rightness, this truth, each truth; and the unbearable impossibility, as finite mortals, of ever being able to express it utterly. Always calling, never arriving… we quiver, trying, alive — just here, just now — and the sound of our voices echoes through space in a single chord: pure harmony/pure dissonance.

62

We haunt this threshold where meaning meets being, and hang breathless in the balance — each moment redeemed, every second condemned — and go on; and while we live as humans it never ends: “Man does not undertake this spanning just now and then; rather, man is man at all only in such spanning.” (MH) [64]

The threshold is the ground-beam that

bears the doorway as a whole.

— Martin Heidegger

63

We come, then, to this “place of arrival… a presence sheltered in absence,” (MH) [65] this place between, this threshold where the struck chord of us hangs echoing. This in-between place where we echo together is ours, the human, our ground-beam. “It is ours to keep” (JS) [66] — it belongs to us, we belong to it; we keep it in each, and we keep it between us. We echo together and listen for what we find to be true — in the world, in ourselves, in what each other says and does — and on that we build. This is how we come to be human: to see and to say, to get it, to get it right; to understand and, going on, to learn, “Both listening and changing,” (JS) [67] in each and between us, thereby becoming; and to make of our becoming some “art… the setting-into-work of truth” (MH) [68] — about ourselves, each other, the world, as “witness to (their) relationship.” The true is in us, all around us, but the “truth… happens in being composed, as a poet composes a poem” (MH) [69] — in us, by us, by our human work, the making intelligible, the telling of the true into truth. In each and between us, from this grounded, groundless ground-beam, human being, “we reach out to build ourselves” (JS) [70] — for ourselves, of ourselves — a human realm: in this place between, “… we interact,” (JS) [71] and, looking back, we see that

64

We have lifted one and another

and another.

We have been lifted by one and

another and another. (JS) [72]

65

We see that, in each and between us, delicately balanced on the truth as we see it, “we build ourselves into a configuration,” (JS) [73] a larger art, “this thing called culture” (JS) [74] — a figure, an image, a structure, a sculpture, a metaphor that echoes up, out of our entirety, to make manifest the truth as we, unified, see it. As we echo together in our human realm, and keep reaching toward each other, keep listening with “an ever more painstaking listening,” (MH) [75] we learn, we build, we become — the human becomes, and we become human. To build the human realm, to compose this delicate truth, in each and between us, is an art, a difficult art, that never ends. It is ours, “ours to keep” — we are born to it, yet somehow it requires our highest and best effort, and

66

We tremble as we do this.

Even after we build, we

tremble. (JS) [76]

67

So the human realm rises, poised on our truth, from this ground-beam, in-between: the human act and art of standing between near and far and impossibly far; between the literal, its significance as we now apprehend it, and what lies beyond our comprehension — that standing-open from which, in each and between us, “matter begins to speak in a new way.” This “interplay… the span that man traverses at every moment” (MH) [77] is what is poetic in us, and “the poetic is the basic capacity for (being) human.” (MH) [78] For us, “poetry… is the primal form of building,” (MH) [79] of coming to understand, of speaking and acting in accord with what we know, of proceeding, participant, into the future. The poetic is our human work —

68

This is what we do

when we do what

we are… (MS) [80]

69

The human realm, where meaning meets being, draws and is drawn, slowly together around the pulse of the true, the impulse for truth, with utterest effort — instinct become art, both inspiration and end, this seeking and making, “at once receptiveness and total concentration,” of truth from the true — our human work, our force toward coherence, our center of gravity.

70

Yet truth, like gravity — vibrant, alive — draws us on: having made, built, composed, woven… a form, a story, a figure, an image… the truth ever truer, spiraling ever wider, “compels as well” its constant unraveling, our constant reweaving, revising, revisioning, evolving… In culture, an image coalesces to clarity, then gradually bends, bows, blurs, and — in “successive” and “continuous” being-composed in each and between us — becomes something new:

71

At each time the openness of what is had to be established in beings themselves, by the fixing of truth in figure…

This… happened in the West for the first time in Greece. What was in the future to be called Being was set into work, setting the standard. The realm of beings thus opened up was then transformed into a being in the sense of God’s creation. This happened in the Middle Ages. This kind of being was again transformed at the beginning and in the course of the modern age. Beings became objects that could be controlled and seen through by calculation. At each time a new and essential world arose. (MH) [81]

72

A new world, the “modern” world — “(we) say its name” — “we tremble as we do this.”

seeing is bereaving.

— Judith Goldman

73

From $00 / LINE / STEEL / TRAIN

74

I.

The basic form is the frame; the photograph of the factory predicts how every one (of the materials) will get used. and I can remember Mark & I talking about the possibility of Lackawanna becoming a ghost town Past (participle) past (participant) past (articulating) an incessant scraping (away), and what would we do. You know — it wasn’t just losing a job in the steel industry, but your entire life, the place that you grew up in was going to be gone. As I scraped (grease, meat, omelettes), the (former) railroad workers and steel workers (still) bullshitting in the restaurant where for eight years I short-order cooked.

*

Who knew

the crisis

from the conditions —

presumably

the Capital [Who] (MN) [82]

75

They heard about all this cracking and breaking away on the news and then they began to search over the internet for information on what was going on. BLUE WHALE On the internet they found an animation of the piece of the Antarctic Pine Island glacier breaking off. BLUE-BREAST DARTER After they found this, they often called this animation up and just watched it over and over on their screen in their dimly lit room. BLUE-SPOTTED SALAMANDER In the animation, which was really just a series of six or so satellite photographs, a crack would appear in the middle of the glacier. BOG BUCKMOTH Then a few frames later the crack would widen and extend itself toward the edges and then the piece would break off. BOG TURTLE… (JS) [83]

76

We were led out into the night,

Persuaded by their bright bayonets,

Dragged by our gowns,

Tied together, trampled. Led

By boys from the neighboring school

Who were no longer boys. Child soldiers,

Eyes cloudy as marbles.

They kicked at us. We marched.

Later, I fled. Hid. Was found. Other girls

Were handed sticks and made

To deliver blow after blow. Expeditious.

I died and was left in plain view, an example

To be whittled by maggots and birds. (TKS) [84]

77

We do not speak about the loading of M1 Abrams tanks, Apache

helicopter gunships, and other equipment on two roll-on/roll-off

ships, the Mendonca and the Gilliland, in Savannah, Georgia…

We do not speak about the Constellation in the Persian Gulf and

the Harry S. Truman in the Mediterranean, each with forty fighter

jets on board, including F/A-18 Hornets and F-14 Tomcats, and

about forty other aircraft. (JS) [85]

78

This is the bar of broken survivors, the club of shotgun,

knife wound, of poison by culture. We who were

taught not to stare drank our beer. The players

gossiped down their cues. Someone put a quarter

in the jukebox to relive despair… (JH) [86]

79

(We do things with an A-bomb, produce effects with an A-bomb, and we do things to A-bombs, but an A-bomb

Is also the thing we do. A-bomb is a name for our doing: Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s

(Power to make war. Is our vulnerability to an A-bomb a consequence of our being constituted

Within its terms? Could an A-bomb injure us

(If we were not, in some sense, A-bomb beings,

(Beings who require an A-bomb in order to be? (JG) [87]

80

How do I say it? In this language there are

no words for how the real world collapses… (JH) [88]

Though the house gleamed with appliances.

— Joy Harjo

81

Heracles was more afraid now than he had been in his whole life. He could accept any challenge but the challenge of no challenge. He knew himself through combat. He defined himself by opposition. When he fought, he could feel his muscles work and the blood pumping through his body. Now he felt nothing but the weight of the world. Atlas was right, it was too heavy for him. He couldn’t bear it. He couldn’t bear this slowly turning solitude. (JW) [89]

82

In the night I watch television to help me fall asleep, or

I watch television because I cannot sleep… (CR) [90]

83

He suddenly thought of Atlas, star-silent. For a second, the buzzing started again, in the usual place, by his temple. He hit his head. The buzzing stopped. (JW) [91]

84

I don’t know, I just find when the news comes on I switch the channel. (CR) [92]

85

There is a button on the remote control called FAV. You can program your favorite channels. Don’t like the world you live in, choose one closer to the world you live in. (CR) [93]

86

Sometimes, this poem wants to wander

Into a department store and watch itself

Transformed in a trinity of mirrors.

Sometimes this poem wants to pop pills.

Sometimes, in this poem, the stereo’s blaring

While the TV’s on mute.

Sometimes this poem walks the street

And doesn’t give a shit.

Sometimes this poem tells itself nothing matters,

All’s a joke. Relax, it says, everything’s

Taken care of. (TKS) [94]

87

My flushing toilet, my hot water, my air conditioner, my health insurance, my, my, my — all my my’s were American-made. This is how I was alive. Or I wasn’t alive. I was a product, or I was like a product… (CR) [95]

88

the president of loyalty recommends

blindness to the blind (WSM) [96]

89

I learned to renounce a sense of independence by degrees and finally felt defeated by the times I lived in. Obedient to them. (FH) [97]

90

With injections of Botox, short for botulism toxin, it seems I can see or be seen without being seen; I can age without aging. I have the option of worrying without looking like I worry… without looking as if anything mattered to me. I could paralyze facial muscles that cause wrinkles. All those worry and frown lines would disappear. I could purchase paralysis. I could choose that. Eventually the paralysis would sink in, become a deepening personality that need not, like Enron’s “distorting factors,” distort my appearance. I could be all that seems, or rather I could be all that I am — fictional. Ultimately I could face reality undisturbed by my own mortality. (CR) [98]

91

The minute you stop fearing death you are no longer… accountable to life. The relationships between the “I” and the “we” unhinge and lose all sense of responsibility… (CR) [99]

92

When we fell we were not aware of falling. We were driving to

work, or to the mall. The children were in school learning subtrac-

tion with guns. (JH) [100]

… but neither light, nor certitude,

nor peace exist.

— Juliana Spahr

93

At the bus stop I say, It’s hard to get a cab now… The woman standing next to me glances over without turning her head. She faces the street where cab after cab drives by with its lights off. She says, as if to anyone, It’s hard to live now. (CR) [101]

94

Beloveds, I haven’t been able to write for days.

I’ve just been watching. (JS) [102]

95

It was coming.

We had been watching since the eve of the missionaries in their

long and solemn clothes, to see what would happen. (JH) [103]

96

Two towers rose up from the east island of commerce and touched

the sky. Men walked on the moon. Oil was sucked dry

by two brothers. Then it went down. Swallowed

by a fire dragon, by oil and fear.

Eaten whole. (JH) [104]

97

When I wake up this morning the world is a series of isolated,

burning fires as it is every morning.

It burns in Israel where ten died from a bomb on a bus.

Yesterday it also burned in the Philippines where twenty-one died

from a bomb at an airport. And then it burned some more a few

hours later outside a health clinic in a nearby city, killing one. (JS) [105]

98

This is not myth.

My body did not sing. It stank. (TKS) [106]

the silence that speaks without speaking,

does it say nothing? are cries nothing?

— Octavio Paz

99

though they hurt us, every breath,

the holes in our sides,

though they (a)re invisible,

underground rivers, caves — (JV) [107]

100

So you, so you go… (ES) [108]

101

And so you go on… (TKS) [109]

102

Forgiveness… for the one who forgives… is simply a death, a dying down in the heart, the position of the already dead. It is in the end a living through, the understanding that this has happened, is happening, happens. Period. It is a feeling of nothingness that cannot be communicated to another, an absence, a bottomless vacancy held by the living… (CR) [110]

103

The loneliness of death is second to the loneliness of life. (CR) [111]

104

This is the body, the sealed unit… (JW) [112]

105

But I say… (JS) [113]

106

The subject who speaks is situated in relation to the other… By offering a word, the subject putting himself forward lays himself open and, in a sense, prays. (EL) [114]

107

I felt it too.

The loneliness?

I let it happen.

By feeling?

By not not feeling. (CR) [115]

108

… yous were wrapped around me and I thought it was this that had

let me dream of windows and doors opening and light entering… (JS) [116]

109

Without promise, without pretense,

A voice calls out. (A) [117]

110

Here. I am here… (CR) [118]

111

here… where the dialogue… begins (A) [119]

112

I say…

I say it’s what one loves.

It’s what one loves, the most beautiful is whomever one loves… (JS) [120]

113

I say it again and again.

Again and again.

I try to keep saying it to keep making it happen. (JS) [121]

114

Again and again…

115

… one and

another and another… (JS) [122]

116

… eleven…

… million …

… people across the globe took to the streets one

recent weekend to protest the war and this gave us all a glimmer.

We talked on the phone about this glimmer.

We read each other’s reports.

We said optimistic things. (JS) [123]

117

Beloveds, we wake up in the morning to darkness and watch it

turn to lightness with hope. (JS) [124]

118

Maybe hope is the same as breath — part of what it means to be human and alive. (CR) [125]

119

Every day is a reenactment of the creation story. We emerge from

dense unspeakable material, through the shimmering power of

dreaming stuff.

This is the first world, and the last. (JH) [126]

120

… now, anywhere

with everyone you love there to talk to.

And to listen. (JV) [127]

121

In recognized it will be heaven (BH) [128]

What’s more important? The beginning

Or the end? That they went

Or that they came back? And what is over?

— Tracy K. Smith

122

Confused, depressed, in despair in the midst of distraction, subjugation, destruction… still, something nags at us. Deep in our gut, some instinct pulls — some persistent urge still “strangely concerns us.” We wonder what it means. Our objective culture explains it away as vestigial, a remnant to be discarded, or an illness to be cured — subjective, irrelevant, unreal; a figment, a specter, a bogey, bogus. We try to ignore it or quell it or kill it… or, we choose to turn toward this slimmest impulse and listen. If we can, as we can, we try to seek, to sift, to sense our way toward some rightness, toward what we find, in each and between us, to be true. As our world unravels and our culture frays, we pick up the broken strands and begin to work at them, reaching, stretching, speaking, connecting, mending, amending, expanding… We begin to weave a way, a place, beyond the “modern” world’s fractured parameters, “listening with an ever more painstaking listening,” riding its impulse — no longer down “the wave of falling… ,” but rising now on “… the converse wave of gathering together.” (JH) [129] The impulse grows stronger, and we grow stronger in it, around it, seeking, saying, doing, making, working our way through the poem, from the true into truth as, each alone, all together, in union and schism, in concert, as chorus, we speak —

123

How Shall We Live? / A Poetics of Matter

WSMerwin I have to trust what was given

WSMerwin to me… the stars

WSMerwin over the shadowless

WSMerwin/AnnieDillard mountain / being

AnnieDillard/MartinHeidegger itself / beings… flung free into nothing other

MartinHeidegger than a drawing

MartinHeidegger/CharlesDarwin toward the center / an instinctive

CharlesDarwin tendency

CharlesDarwin/EleniSikelianos to acquire an art / to travel the deeps of air

EleniSikelianos/CeciliaVicuña with no fear / listening

CeciliaVicuña/WSMerwin to matter / what does it

WSMerwin not remember

WSMerwin in its night

WSMerwin/MartinHeidegger and silence / the soundness

MartinHeidegger of worldly existence — this

MartinHeidegger is what is

MartinHeidegger/EleniSikelianos to be said / to stir words

EleniSikelianos/CeciliaVicuña into thoughts like things / sacred

CeciliaVicuña/CeciliaVicuña things I had to arrange / the weaving

CeciliaVicuña/CeciliaVicuña of words / to follow their

CeciliaVicuña/RainerMariaRilke wishes / what’s your urgent

RainerMariaRilke charge, if not

RainerMariaRilke/WilliamBlake transformation / the eyes of fire

WilliamBlake the nostrils of air, the mouth of water

WilliamBlake/WB/RainerMariaRilke earth / Infernal Genius / speak

RainerMariaRilke/WaltWhitman and testify / Who

WaltWhitman/WSMerwin goes there? hankering, gross, mystical, nude / more beautiful

WSMerwin after every wound /

JulianaSpahr one

JulianaSpahr and another

JulianaSpahr/RainerMariaRilke and another / whoever

RainerMariaRilke/JulianaSpahr we finally may be / we

JulianaSpahr/MartinHeidegger build and we come and we reach / but

MartinHeidegger the saying

MartinHeidegger is hard — the hard thing

MartinHeidegger is to accomplish

MH/MarciaCasey/RainerMariaRilke existence / we say its name / oh…

RainerMariaRilke in a way that

RainerMariaRilke things themselves never

RainerMariaRilke dreamed of /

LaurieGudim just so /

JulianaSpahr so it might

JulianaSpahr matter

Editor’s note: The original layout of this page made it difficult to reproduce in HTML.

Here is a JPG file of the page. — Editor.

[1] Charles Darwin, in Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct, New York: William Morrow and Company, 1994, 19–20.

[2] Robert Finch and John Elder, eds., The Norton Book of Nature Writing, 1st ed., New York: W. W. Norton, 1990, 28.

[3] Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, New York: Harper & Row, 1974, 131.

[4] Cecilia Vicuña; translated by Esther Allen, “Quipoem,” ed. M. Catherine de Zegher, The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña, Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997, q.89.

[5] Rainer Maria Rilke, in Martin Heidegger, translated by Albert Hofstadter, Poetry, Language, Thought, New York: Harper & Row, 1971, 99.

[6] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emerson’s Essays: First and Second Series Complete in One Volume, New York: Harper & Row, 1926, 382.

[7] Ibid., 262.

[8] Jed Rasula and Steve McCaffery, eds., Imagining Language, Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1998, 330.

[9] Ibid., 330.

[10] Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, New York: Harper & Row, 1974, 131.

[11] Epicurus, in Rasula and McCaffery, 534.

[12] Martin Heidegger; translated by Albert Hofstadter, Poetry, Language, Thought, New York: Harper & Row, 1971, 201–202.

[13] Ibid., 93.

[14] Brown, Norman O. Love’s Body, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, 155.

[15] Newton, Isaac, “Law of Universal Gravitation,” in “How does gravity work?”. April 1, 2000. http://science.howstuffworks.com/question232.htm (March 10, 2008).

[16] Vicuña, q.136.

[17] Rasula and McCaffery, 537.

[18] Ibid., 511–512.

[19] Vicuña, q.136.

[20] Rainer Maria Rilke; translated by A. Poulin, Jr., Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977, 63.

[21] Heidegger, Martin, 102.

[22] Dillard, 15.

[23] Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct, New York: William Morrow and Company, 1994, 339.

[24] Emerson, 276.

[25] Ibid., 385.

[26] Ibid., 382.

[27] Heidegger, 224.

[28] Ibid., 223.

[29] Ibid., 229.

[30] W.S. Merwin, Migration: New and Selected Poems, Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2005, 389.

[31] Heidegger, 72.

[32] Dillard, 129.

[33] Ibid., 82.

[34] Emerson, 288.

[35] Vicuña, q.136.

[36] Ibid., q.12.

[37] Ibid., q.67.

[38] Casey, Marcia, “Writing the Creation Story,” in Pitkin Review, Fall (2007): 6–7.

[39] Heidegger, 71.

[40] Ibid., 71.

[41] Andrey Bely, in Rasula and McCaffery, 331.

[42] Dillard, 8.

[43] Ibid., 67.

[44] Ibid., 179.

[45] Rilke, 61.

[46] Ibid., 61–63.

[47] Dillard, 181.

[48] Ibid., 270.

[49] Rilke, 61.

[50] Ibid., 67.

[51] Rasula and McCaffery, 130.

[52] Dillard, 129.

[53] Merwin, 522.

[54] Rilke, 63–65.

[55] Ibid., 61.

[56] Rasula and McCaffery, 53.

[57] Maurice Leenhardt, in Rasula and McCaffery, 372.

[58] Emerson, 265.

[59] Vicuña, q.131.

[60] Dillard, 240.

[61] Heidegger, 196.

[62] Ibid., 201.

[63] Ibid., 201.

[64] Ibid., 218.

[65] Ibid., 197.

[66] Juliana Spahr, Fuck You — Aloha — I Love You, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001, 55.

[67] Ibid., 54.

[68] Heidegger, 72.

[69] Ibid., 70.

[70] Spahr, Fuck You, 61.

[71] Ibid., 61.

[72] Ibid., 75.

[73] Ibid., 64.

[74] Ibid., 61.

[75] Heidegger, 214.

[76] Spahr, FY, 64.

[77] Heidegger, 221.

[78] 78 Ibid., 226.

[79] Heidegger, 224.

[80] Matthew Shenoda, Somewhere Else, Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2005, 39.

[81] Heidegger, 74.

[82] Mark Nowak, from “$00 / LINE / STEEL / TRAIN,” in Claudia Rankine and Lisa Sewell, eds., American Poets in the 21st Century: The New Poetics, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007, 320.

[83] Spahr, Juliana, “from Unnamed Dragonfly Species” in ecopoetics 2 (2002): 146.

[84] Smith, Tracy K., Duende: Poems, St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2007, 65.

[85] Juliana Spahr, This Connection of Everything with Lungs: Poems, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, 43.

[86] Harjo, Joy, How We Became Human: New and Selected Poems 1975–2001, NY: W.W. Norton, 2002, 67.

[87] Goldman, Judith, DeathStar/Rico-chet, Oakland, CA: O Books, 2006, 106.

[88] Harjo, 67.

[89] Winterson, Jeanette, Weight, NY: Canongate, 2005, 71–72.

[90] Rankine, Claudia, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric, St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2004, 29.

[91] Winterson, 116.

[92] Rankine, Don’t Let, 23.

[93] Ibid., 24.

[94] Smith, 14.

[95] Rankine, Don’t Let, 93.

[96] Merwin, 169.

[97] Fanny Howe, in Rankine, Don’t Let, 128.

[98] Rankine, Don’t Let, 104.

[99] Ibid., 84.

[100] Harjo, 104.

[101] Rankine, Don’t Let, 113.

[102] Spahr, This Connection, 42.

[103] Harjo, 198.

[104] Harjo, 198.

[105] Spahr, This Connection, 56.

[106] Smith, 65.

[107] Valentine, Jean, Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems 1965–2003, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004, 33.

[108] Sikelianos, Eleni, The California Poem, Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2004, 35.

[109] Smith, 79.

[110] Rankine, Don’t Let, 48.

[111] Ibid., 122.

[112] Winterson, 14.

[113] Spahr, This Connection, 46.

[114] Emmanuel Levinas, in Rankine, Don’t Let, 120.

[115] Rankine, Don’t Let, 58.

[116] Spahr, This Connection, 46.

[117] Adonis, Mihyar of Damascus: His Songs, Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2008, 111.

[118] Rankine, Don’t Let, 130.

[119] Adonis, 39.

[120] Spahr, This Connection, 46–47.

[121] Ibid., 47.

[122] Spahr, Fuck You, 75.

[123] Spahr, This Connection, 58–59.

[124] Ibid., 15.

[125] Rankine, Don’t Let, 119.

[126] Harjo, 104.

[127] Valentine, 124.

[128] Hillman, Brenda, Cascadia, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001, 60.

[129] Harjo, 99.

Adonis. Mihyar of Damascus: His Songs. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2008.

Brown, Norman O. Love’s Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

Casey, Marcia. “Writing the Creation Story,” Pitkin Review, Fall (2007): 6–7.

Dillard, Annie. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Emerson’s Essays: First and Second Series Complete in One Volume. New York: Harper & Row, 1926.

Finch, Robert and John Elder, eds. The Norton Book of Nature Writing, 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

Goldman, Judith. DeathStar/Rico-chet. Oakland, CA: O Books, 2006.

Harjo, Joy. How We Became Human: New and Selected Poems 1975–2001. NY: W.W. Norton, 2002.

Heidegger, Martin; translated by Albert Hofstadter. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

Merwin, W. S. Migration: New and Selected Poems. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2005.

Newton, Isaac, “Law of Universal Gravitation,” in “How does gravity work?” April 1, 2000. http://science.howstuffworks.com/question232.htm (March 10, 2008).

Pinker, Steven. The Language Instinct. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1994.

Rankine, Claudia, and Lisa Sewell, eds. American Poets in the 21st Century: The New Poetics. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007.

———. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric. St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2004.

Rasula, Jed, and Steve McCaffery, eds. Imagining Language. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1998.

Rilke, Rainer Maria; translated by A. Poulin, Jr. Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

Shenoda, Matthew. Somewhere Else. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2005.

Sikelianos, Eleni. The California Poem. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2004.

Smith, Tracy K. Duende: Poems. St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2007.

Spahr, Juliana. “from Unnamed Dragonfly Species,” ecopoetics 2 (2002):146–149.

———. Fuck You — Aloha — I Love You. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

———. This Connection of Everything with Lungs: Poems. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Valentine, Jean. Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems 1965–2003. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

Vicuña, Cecilia; translated by Esther Allen. The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1997.

Winterson, Jeanette. Weight. NY: Canongate, 2005.

Marcia Casey

Marcia Casey has a BA in Interdisciplinary Studies (language, literature, and environmental studies) and has recently completed her MFA in poetry at Goddard College. She lives, works and writes in Wyoming.