| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Roberto Tejada and Jacket magazine 2010.

See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/at-tejada-roberto.shtml

Back to the A Tonalist feature Contents list

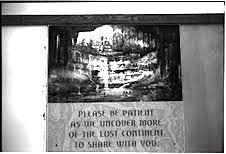

[after Rubén Ortiz-Torres]

Photo by Rubén Ortiz Torres

PLEASE BE PATIENT

AS WE UNCOVER MORE

OF THE LOST CONTINENT

TO SHARE WITH YOU

Prismatic light-beams and motion to so enhance the monuments

encouraging society, goliath in its seizure of the earth people,

former technology of bone, dawn’s incessant yowling, renewed skin

a sort of liquid flesh: that we wish, even as tutors conveyed

the alphabet to faraway townships — need, even with our rhetoric

of puzzlement, faith overturning this makeshift enclosure

this great asylum in the ancient city of the Indies — to salvage

our nation from disgrace and despairing not, to us was tendered

the mistress builder most suitable to bestow the colossal head

on ground shuddering, all day blood and gold great mother

as when we found it, no longer migrant, holy in the highest

glory, honor and renown to Her most worthy everywhere

throughout all ages and generations, amen. There were two kinds

of breathing in the night; one that was jelly-colored and semi-solid

Photo by Rubén Ortiz Torres

the other stunted in rapture or awestruck in such unbreakable blaze

as with incense and coagulates, to the artery, to cells that dividing

did duplicate, divide and duplicate again: cross-eyed, very close

to the triangular nose, upper teeth in baskets and bundles

like a shipment of newspapers very old admission stubs a cheap

notebook — all things artless, half real anyway — if a casket

if a prankster effigy, reflected face in a thousand interlocking

parts of what followed from the center point where I am

outside the fiberglass capital as in the one it beckons from a middle

order meaning. Out of isolation and forth to the deputy recitalist

of myself in surrogate space, precise eye of a properly positioned

witness like the visitor contained by sound full ceremony

perverse in aim as even this strange novelty’s current role was

no how natural in relation to the person of the world I was

but a careful construction in the urgent theme that was a single

death, in the modest epic most immediate of our demise, I mean

recall, translucent and disposable, the remaining corpses. World

that was smaller then. Were we so immune to escalation had

there been more to fabricate in the lost continent, and to relay?

I acknowledged the cranium from the old populace and paid

my tribute to the new passing reference in degrees of routine or

memory as was prone to fit on gossamer sail. “The laboring

populace had lost its faith,” bemoaned the boatman, “You work

if you intend to eat, already by mizzen truck with the factory

vanguard a millennium or two of meteoric growth in on-shore

commerce while the class struggle, while the opposing Party

adored the technocrats who made vulnerable, ignored best practice

inauspicious to the earth folk who bestowed us no distinction

as with the likes of blue-collar wage labor output production lines

given to befriending fire hydrants and phone booths, from the hard

workers at the local megastore to the lot of us wretched who

learned to accept your differences and embrace our flaws.”

Boomtown hub, big-money high style and ostentatious wealth

long replaced even in the labor union, “I used to think ‘model

worker’ was the title for ordinary bodies that toiled hard rules

and regulations notwithstanding,” the racketeer reported.

“But now ‘migrant workers’ like me also merit the distinction,

proving once again the elected culture populuxe in the atomic

age meets the Temple of Inscription’s slogan to oppose reelection

of the General stripped of revolutionary nuance Temple of the Sun

telling Temple of the Count to salvage Temple of the Foliated

Cross sharp at the oncoming ax blades of Aqueduct wind glint

the vertical distance relative to the reference point of an edifice

projected onto a plane vertical to Temple of the Lion

sleep bundled mouth wide open as though to bellow in siren

Structure XII, phase six devoid of shading, ritual appended

to official documents chiseled to a rhythm other than my own.

Because they feared the perils and aftermath in ways more than

they loved the light that would lead them sometimes asunder,

Dynastic-Novelty-of-All-Modern-Convenience to resemble

a product sold inside as the alphabet attraction of its architects

a theory if I didn’t doubt there was a God, killed by coagula-

tion a land could so venerate as to amuse. God who? Not enough

to claim by open gashing of the solar plexus — queen’s bishop

to Huitzilopochtli! — “I was awakened at one in the morning:

a terrible moan. I thought maybe thieves… . Rain otherwise drip-

ping all over this household, and still no arrival. I’m desperate.

Rainwater refusing to obey, if the drainpipe moans are ended

if only this, as nothing else.” It was time for my replacement

mother (a cactus, flesh that wasn’t flesh from the flaming mortar

of antiquity) to declare the northern desert exile for all measure

of paterfamilias: hyperkinetic emblem in saturated color after

the mash-up act between neighboring nations, arsenal of food

stuff and lower transit by request, sensations new to denizens

demanding entertainment of the ignited variety, cartoon cigar

that detonates to singe my face into an orifice too of blinking

light: or pyramid permitting matters — head first — to so decline.

***

Roberto Tejada

Roberto Tejada (Los Angeles, 1964) is the author of several poetry collections, including Mirrors for Gold (Krupskaya, 2006) and Exposition Park (Wesleyan University Press, 2010); he founded and continues to co-edit the journal Mandorla: New Writing from the Americas. He is, as well, the author of art histories that include, most recently, National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), and Celia Alvarez Muñoz (UCLA/CSRC; University of Minnesota Press, 2009). Tejada has published critical writings on contemporary U.S., Latino, and Latin American artists in Afterimage, Aperture, Bomb, The Brooklyn Rail, SF Camerawork, and Third Text. He writes: “Musically, my writing thrives as the offspring of Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite as coupled to the vocals of Exene Cervenka + John Doe on so many of X’s recordings, that unsettling harmony driving the trilogy Los Angeles, Wild Gift, and Under the Big Black Sun. Visually, with an object-based idiom that gleans only transitory insight, I seek a poetry restless in its relation to the culture concept, and the image environment’s relation to the letter; verbal performances akin to the photographs of Rubén Ortiz Torres, as frames for surviving the onrush of historical change.”

Rubén Ortiz Torres: self portrait

Rubén Ortiz Torres (Mexico City, 1964) was educated within the utopian models of republican Spanish anarchism, even as he soon confronted the tragedies and cultural clashes of the postcolonial third world. The son of two Latin American folk musicians, he came to identify more with urban punk music. Ortiz Torres first attended the oldest and one of the most academic art schools of the Americas (the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City; he went on to one of the newest and most experimental (Calarts). After enduring Mexico City’s earthquake and pollution, he moved to LA with a Fulbright grant to survive riots, fires, floods, more earthquakes, and Proposition 187. His artwork took the form of paintings, photographs, objects, installations, videos, and films. His work has shown at many international exhibitions and film festivals and is featured in collections that include MoMA New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoCA Los Angeles, the California Museum of Photography, the Centro Cultural Art Contemporáneo, Mexico City, and the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, among others. After showing his work and teaching art around the world, he now realizes that his dad’s music was in fact better than most rock-n’-roll.