| Jacket 39 — Early 2010 | Jacket 39 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 3 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Vincent Katz and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/39/katz-vanitas.shtml

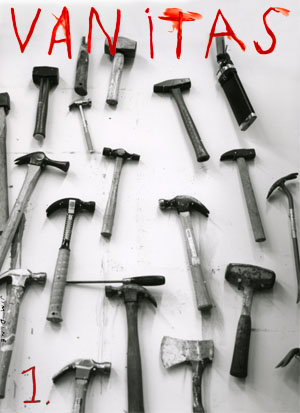

1

I had not edited a poetry journal since high school. In those days, in the mid-’70s, my models were the beautiful independent poetry magazines of the 1960s and ’70s such as Ted Berrigan’s “C,” Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh’s Angel Hair, Larry Fagin’s Adventures in Poetry, Bill Berkson’s Big Sky, Peter Schjeldahl and Lewis MacAdams’ Mother, The World, Kenward Elmslie’s Z press, and others. What I liked about them was the combination of first-class writing with first-class art on the covers, put together in the most economical fashion.

2

Inspired by that model, Paul Schneeman and I edited Open Window through three issues, plus a one-off called Hit Singles. We published, in addition to our own efforts, work by Ted Berrigan, Jim Carroll, Steven Hall, Bob Rosenthal, James Schuyler, Simon Schuchat, John Yau and Paul’s brother Elio.

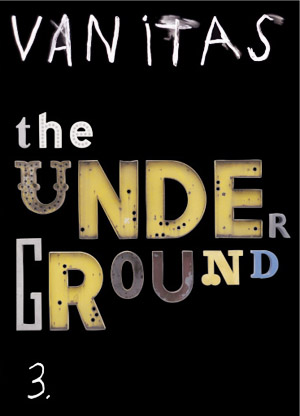

3

Fast forward to 2002. I was in Rome ostensibly to work on translating Sextus Propertius but by one of those quirks of fate had been given the responsibility of organizing an exhibition about Black Mountain College at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. I also had twin boys who were two years old. We were getting ready to leave New York for Rome when 9/11 hit. I went to the library for a week and read about Islam, read the Qu’ran, read Peter Lamborn Wilson, Mamoun Fandy, and others. I could not make sense of what was happening and responded the only way I knew how: by research. I remember clearly those mystified days in the New York Public Library on 42nd Street. There were many people there, as usual, but all seemingly more intent than usual on their books, as though, if they looked up, the floor under them might disintegrate, the massive wooden tables and chairs be smashed to splinters.

4

I felt really out there somewhere, on a limb. I did not feel part of any group, or even a community. I was living in Rome, separated from the poetry community of New York City. I met a few fascinating poets in Rome but did not feel part of their world. I was studying Black Mountain College and The Black Mountain Review and was impressed by Charles Olson’s teaching there that one should put out one’s own poetry, should design and find the means to print it, not wait for approval from above. I was likewise surprised by Robert Creeley’s observation that possibly only 200 copies of each issue of the BMR made it into the hands of people the editors were trying to reach.

5

I wanted to make my voice heard in terms of poets I liked who were currently working and decided to start a magazine. The knowledge of what is required to do a magazine had prevented me during all those years, but now I needed to do it. I solicited poems from a number of people for the first issue and asked Jim Dine to do the cover (Dine was germane to the founding of the magazine and created the logo used for each issue). I remember I did not solicit work from Robert Creeley, even though I knew him, and he had visited us in Rome. I wanted to present him with the first issue as a fait accompli.His unexpected death, which rocked the poetry world, made that an impossibility. Ezra Pound had advised Creeley on the necessity of contributing editors, colleagues who could add what the editor did not know was missing. Vanitas has been extremely fortunate to have been able to draw over the years on the editing talents of Martin Brody, Jordan Davis, Elaine Equi, and Raphael Rubinstein.

6

Each issue would have a tonic word setting the tone. There would be an attempt to gather voices from around the world and a commitment to including writings by artists whose primary forms were non-literary. We engaged an emphasis on critical writings, some of which would have political or social content. There would be a necessity of coming to grips with political realities, this particularly urgent as we were in the midst of the dark Bush-Cheney years. The first issue was subtitled The State. I meant it literally as an examination of what the state was capable of, but also I knew that poets would take the word into extended meanings, states of being. Dine provided some of his best poem-paintings. The second issue was subtitled Anarchisms, and who better to illustrate the diversity of that concept than Kiki Smith? We also had a supplement of West Coast writers in that issue; Stephanie Young was very helpful in suggesting people for that. The third issue took a different bent, with the subtitle Popular Song. We had left the overtly political for the poetically subversive. Jack Pierson provided the images. The most recent issue is on Translation, and this turned into a blockbuster, with poets from Sappho to Laura Solorzano translated by an array of excellent writers. As always, there is a fascinating multiplicity in how poets respond to the ideas being broached in each issue. Translation is not only an act but a state of mind. Francesco Clemente created a visual piece whose translucence is central to its identity as image. There is also a selection of electrifying poem-works by Brazilian concrete poet Augusto de Campos.

7

I have learned an enormous amount from editing a poetry magazine, mainly what it means to be part of the poetry world, i.e. what it means to be a human being. You are able (are allowed) to make known your choices regarding the work people are doing, and that allowance is made because you are engaged in a transaction, a moving of poetry from one region to another, and particularly from the poet’s private space to the public space of sharing. Poetry thrives on exchange, as opposed to commerce. I always feel, when someone sends you their current work, it’s a little like curating an exhibition. As an editor, you can sense very clearly the moment the writer is in. What matters is capturing that moment, not finding the “best” piece someone has sent. The pieces need to work together with other pieces in the issue. It is sometimes hard to have the overview until it is all over.

8

What I really like is when a magazine gets returned, and it has scribbles on it and postmarks, and I realize this thing is an artifact. It has gone out into the world and become something on its own.

Vincent Katz photo Vivien Bittencourt, Vienna

Vincent Katz is a poet, editor and translator. He is the author of Alcuni Telefonini (with art by Francesco Clemente) and Judge (with art by Wayne Gonzales. Katz translated the complete extant poems of Sextus Propertius, for which he received the National Translation Award. He is the publisher of Vanitas magazine and Libellum books.