| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tad Richards and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/r-loden-rb-richards.shtml

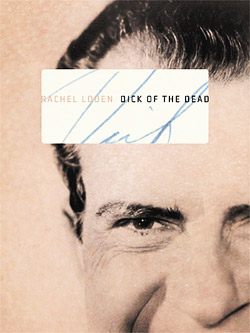

Rachel Loden

Dick of the Dead

reviewed by

Tad Richards

Ahsahta Press, Boise, ID. 104 pp US$17.50 · ISBN-10: 1934103071 ISBN-13: 978-1934103074

Rachel Loden

1

Rachel Loden’s relationship with Dick Nixon is complex and chimerical, as is the persona she creates in her poems. There are as many Dicks as there are Rachels, and they perform a dance which is part gavotte, part boogaloo, with Rachel spinning away at intervals to join other partners or perform solo turns, balletic to breakdance, spinning on her toes or her head.

2

Her first dancing partner in her new collection, Dick of the Dead (Ahsahta Press) is J. Edgar Hoover, who gives her a quick turn around the floor with this epigraph:

3

What are the facts?

Was there any pumpkin

involved at all?

4

And with that, Loden opens the door for Rachel into a strange politico-sexual world in which Cinderella’s fairy godmother is Whittaker Chambers, and in which her pumpkin (which may or may not turn into a carriage) also may or may not be a pumpkin — its secret microfilm actual or imaginary, but always damning.

Section 5

Once into this world, Rachel will not meet her Dick of the Dead right away. The first name on her dance card is Hugh Hefner, and Loden casts Rachel as Miss October,

6

… the girl

Of drifting leaves, cold cheeks

And passionate regrets.

7

Rachel leads in this dance. She is the ignis fatuus whose airbrushing is done by Jack Frost; she knows that the dance of no veils is also the dance of death,

8

… the centerfold of gay

Pretense, the girl who says

We’re at our blondest

And most perilously beautiful

Right before we check out

Of the manse.

9

Caught up in Rachel’s dance, we’re also caught up in Loden’s choreography, precise and haunting at the same time, blending the language of pop culture with the language of the artist. This is often tried, rarely attained, and almost never with the poetic intensity that Loden achieves. At the end, her Miss October is mildewed but forever nubile, reminding “damp boys,” now grown old as Hef,

10

… how many

Playmate-months

Are gone, how many rooms

Stand empty, shutters

Drawn, the last girls slipped

Away in bright October.

11

It’s three poems in before Nixon makes an appearance, and what’s he doing here? We first see him dead but gleeful, his memory of the Cold War a manic frolic with Brezhnev, for whom death has been final in a way it will never be for Nixon.

12

Nixon lives on because Loden breathes life into him, and in Dick of the Dead that’s a different quality of life than it was in Hotel Imperium. The Nixon poems in that earlier collection were about Nixon; Loden seemed to be writing them out of a unique understanding of Dick Nixon the persona. Nixon seems to have returned in these poems not because Loden – or Rachel – understands him, but because he understands Rachel, and she is the center of the book.

13

More than politics, more than death, although there’s plenty of both to go around, Dick of the Dead is about sexuality. They’re bound up together – politics and sex and death – but they’re not bound inextricably; it only seems that way. Nixon and his dick cheat death; Rachel separates herself from it―Miss October leaves empty rooms behind her, but she goes on forever, naked with staples in her navel, like Keats’s bold lover, but unlike Keats’s lover she can kiss, she can fuck, she can explore or imagine a panoply of sexual personae, with Nixon as her spirit guide, “As diaphanous as Bush’s / brain, as feverishly sensitive as Cheney’s heart // I lived in those times, yet I was free.”

14

Nixon, it seems, can enter Rachel at will, although he withholds his actual dick of the dead until late in the book. But early on, he enters her femaleness, in

15

… a room

where clothes, not made of paper, are draped over a chair.

They are so simple in their loveliness, the blue brassiere

that fits the breasts out, separating them with lace. I’ll have,

said Trembling, a dress blue as the stars, and shoon

of shining copper for my feet. It could happen. Mayhap

after a last smile from Evelina, who slowly wheels her heavy

many-dialed machine away. The heart murmurs, talking

a very little to itself. I am Aschenputtel, it says, also known

as Drella, known as Tattercoats, known as Cinder Thing.

Do not cross me. For often I am permitted to lie spreadeagled

on a scroll of paper, reading a colorful magazine.

Most days I wear clothes…

16

Try to figure out the sexuality of that one (from “Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Station”). He starts out as a cross-dresser, then becomes the body he’s mimicking, with real breasts. The station he’s permitted to return to is her. His body flutters its last, flatlines, the machine is wheeled away, but its work, like the machines in Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein, is done. He’s now… who? Drella―the name Lou Reed gave to that prince of androgyny, Andy Warhol – a combination of Dracula and Cinderella. She’s Cinder Thing – Cinderella as a thing, Cinderella with a thing, a thing made of cinders – the dick of the dead. She can be Nixon, devouring Miss October in her colorful magazine, clothed and powerful, or Miss October, spreadeagled on a scroll of paper, sexually available. In any event, the station is “not Terminus” – he / she will be moving on. There’s more sexuality to explore – and since there are no boundaries, not gender, nor even death, the exploration all takes place at the boundaries.

17

By “My Angels, Their Pink Wings,” the gender boundaries are essentially obliterated (not that they can’t return, like Nixon from the dead). The poem begins with a first person narrator accepting the fact that the angels are indifferent to him (presumably him―Nixon―since he’s the one with a better entrée to angels). (See Marjorie Perloff on this poem’s nod to Rilke in Jacket 14.) So he turns from indifference to politico-sexual yearning―to kiss a “firm and pliant” Lenin in his sarcophagus, to lie in state, firm and pliant and sexual and dead,

18

… inside the Hall

of Pillars, in the echoes of the Capitol

Rotunda […]

19

… except maybe it’s not Dick. Maybe it’s Rachel, longing to be

20

[…] cooing to my tricky

one, crooning to my trembling Republic.

21

Either way. Both are tricky, both are sexually amorphous and unafraid of it.

22

About halfway through the book, lesbians make an appearance. They seem an island of sexual sanity. Rachel seems to love the sound of the word, the sensuality of its liquids and sibilants and mutes, and she yearns after the sensuality of all that “lesbian” suggests. This may be the one part of herself where she can find a sexual safe harbor, completely free from Nixon. She pines after lesbians in two poems, but most poignantly after arctic lesbians. When they become summery succulent lesbians, they’re really beyond her reach.

23

In many ways Little Richard, who also is given voice in a poem, is Rachel’s surrogate: wild, bisexual, perverse and orgiastic, he becomes desexualized, speaks as a neutered academic, hides his virginal vagina under nonexistent petticoats.

24

Nixon himself withholds his dick of the dead until nearly the end of the book. In “My Picnic With Dick” he touches her, kisses her, fingers her, seduces her with a webcam, Chou En-Lai, and Martha Mitchell. Not the seduction of choice for everyone. But this is Nixon, whose sexuality is not unlike that of Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death, and this is Rachel.

25

And maybe not even the lesbians are a refuge from Nixon’s relentless challenge to geopolitical sexuality. In “Dick of the Dead,” that very dick is revealed to be a strap-on. Maybe.

26

Death plays a not insignificant role in this collection, although it’s not always (or even usually) permanent. What is permanent is cruelty. It survives from the Stone Age to the cyberage:

27

Here is a Stone Age axe, a catapult,

a battering ram. Ten thousand lines

of code fly through your hands.

28

It travels through one war after another: mankind’s endless war, whether it’s fought by Teddy Roosevelt or John Wayne or Donald Rumsfeld or frightened kids (“Sympathy for the Empire”). In “The Toy Box of My Intentions,” George Bush makes his bloodthirsty appearance:

29

The boy-president plays with you

whenever, somewhere in the world,

a wedding party

is in sudden need of slaughtering;

30

And it reaches its apotheosis as torture. “A Redressed Poet That Seems Living, How to Make Him Sing” is one of the most remarkable sustained pieces of viciousness I’ve ever seen in a poem; it made my flesh crawl.

31

Her horror has a Grand Guignol relish, but that’s never the main thing. She has a piercing eye for the truly horrific:

32

… How is it

that we’re faced again with what’s gone hideously

wrong―the giddy scramble as the ones we love

run wild-eyed through the laboratory,

the rabid grins

of these irradiated bunnies, our best friends?

33

And when sex seems at its most pleasant, a little vacation from the polymorphous perversity of her Hefs and Nixons and Little Richards, when she gets to fuck the emperor of heaven, “a nice guy with a Pekingese,” it becomes impersonal―she’s part of the emperor’s assembly line, like Scheherazade, and one can’t help but suspect that a really awful depravity lies behind the emperor’s smiling façade, and his little dog too.

34

Rachel Loden writes a tightly controlled free verse, calling upon a range of references that continually surprise, and always seem to fit. She plays every possible variation on her themes, but is not their slave. With her sex and her death and her torture, she has created a political poetry for our time, certainly the most original and quite likely the most effective political poetry written by a contemporary American.

Tad Richards

Tad Richards’ most recent poetry collection is Take 5: Poems in 5/4 Time from Ye OIde Font Shop Press. He is president and artistic director of Opus 40 (http://www.opus40.org), the monumental environmental sculpture in Saugerties, NY. His novel, Nick and Jake (co-written with Jonathan Richards) will be presented on the Internet this fall in serial form and as a podcast featuring Alan Arkin, Tom Conti, former ambassador Joseph Wilson and Valerie Plame. He writes a regular column on writing at http://www.examiner.com/x-2862-NY-Writing-Careers-Examiner.