| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 15 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Kyle Schlesinger and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/jwd02-schlesinger.shtml

Back to the Jonathan Williams Contents list

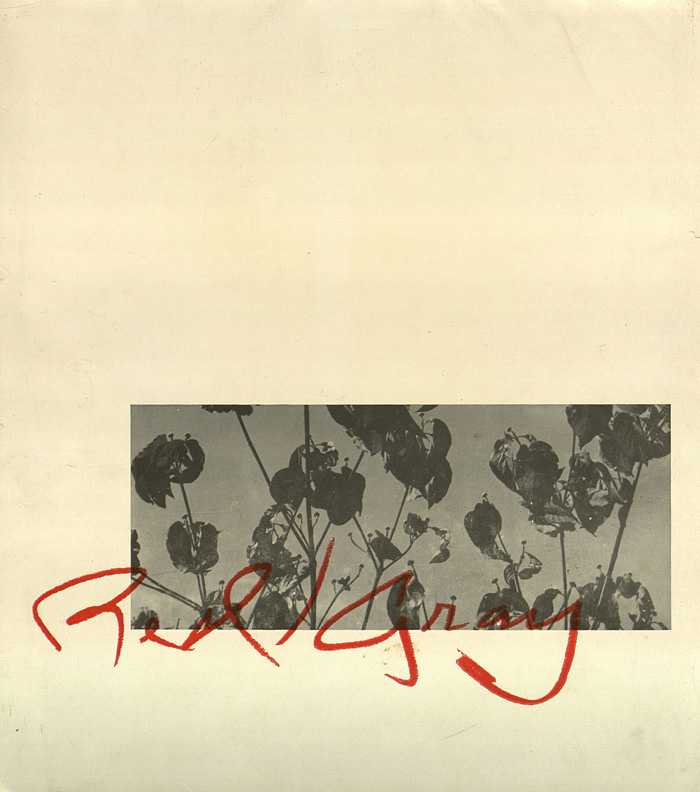

1

The Jargon Society did not begin with Charles Olson’s mighty Maximus, but with a much more modest idea. Before heading down to Black Mountain College from Chicago in the early fifties, Jargon’s founder, Jonathan Williams, went to San Francisco where he met mentors Kenneth Patchen, Robert Duncan, Kenneth Rexroth, and Henry Miller for the first time. It was there that he also met his contemporary David Ruff, a painter from New York who ran The Print Workshop between 1950 and 1955. Ruff taught etching and engraving, published some poetry (mostly Patchen), and gained notoriety in the Beat scene for printing Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s own Pictures of a Gone World, the first book in the infamous City Lights Pocket Poets series, in 1955. It was no marvel of printing (the poems weren’t so hot either), but City Lights quickly became one of the most commercially successful literary publishers in San Francisco.

2

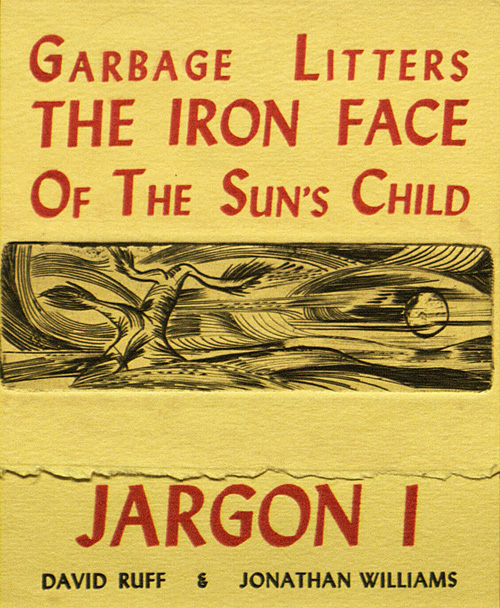

The lesser-known, although far more significant publication to emerge from The Print Workshop wasn’t even a book, but a piece of ephemera produced on the fly. Ruff’s 1951 collaboration with Williams, whose “Patchenesque” poem met Ruff’s image on a small, single sheet of yellow paper, is perhaps best described as a handbill. Ruff carved his image into copper plates (the same form of relief etching that William Blake used to create his own illuminated poems more than a century earlier) and printed the text from handset Lydian type, a distinct calligraphic sans serif designed by Warren Chappell for American Type Founders in 1938. Its publication on June 25, 1951 in an edition of just fifty copies marks the beginning of one of the greatest of the great postwar American private presses.*

3

I bet more people will read this poem within a day of its online debut than the sum of readers who have seen the first edition (published nearly six decades ago):

4

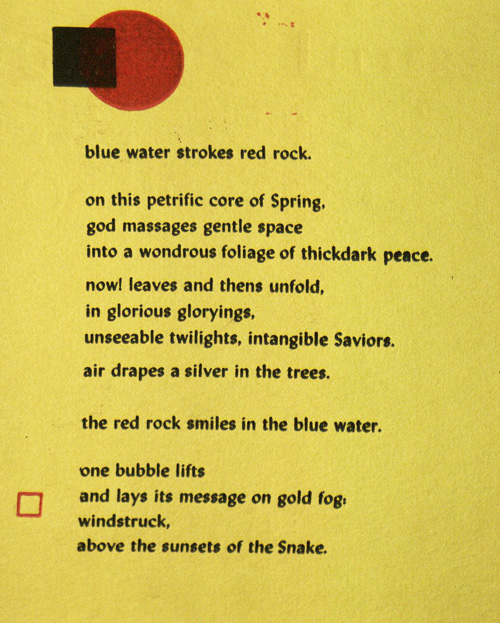

GARBAGE LITTERS THE IRON FACE OF THE SUN’S CHILD

blue water strokes red rock.

on this petrific core of Spring,

god massages gentle space

into a wondrous foliage of thickdark peace.

now! leaves and thens unfold,

in glorious gloryings

unseeable twilights, intangible Saviors

air drapes a silver in the trees.

the red rock smiles in the blue water.

one bubble lifts

and lays its message on gold fog:

windstruck,

above the sunsets of the Snake.

5

While The Jargon Society may forever be marked by Williams’s stint as a student at BMC, what did not change (paraphrasing Olson) was the will to change. Faced with the constant financial pressures that so often come with private press ventures, one wonders why Williams (unlike Ferlinghetti) didn’t pimp his past by publishing books that would cater to the interests of BMC enthusiasts? Or sell nostalgic kitsch to tourists in Asheville? Or peddle high-end works of art by BMC alumni in a New York City gallery? True to the ideals expressed by BMC’s founder John Andrew Rice, who said that “… all college should be in tents – when they fold, they fold,” Williams moved on, taking with him the ideas, rather than the commodities, the College had to offer. In fact, he was pretty much done publishing the Black Mountain poets (as such) by the mid-sixties when he was a young man still in his mid-thirties. Given the same opportunity in San Francisco, Ferlinghetti made City Lights Books a tourist destination, a spectacle amongst the sites and hype.

6

Williams stayed true to the integrity of private press culture (spawned by William Morris and his Kelmscott Press in the late 1800s) by making it his business to publish the poets he wanted to read in the form that he wanted to read them regardless of their commercial viability. While there were deluxe editions from time to time, these were the exception rather than the rule. It seems likely that these were primarily designed to be sold to special collection libraries and private collectors in order to raise money for the press’s populist publications (not an uncommon practice). One of the characteristics most often admired in The Jargon Society is the unique design, uncompromising manufacturing standards, and use of high-quality (not extravagant) materials – not sumptuous, just well made. Williams claimed to have lost money on almost every book be published, and relied on the support of grants from individual benefactors and organizations to keep afloat. The range of poets and artists whose energy and ideas gained the support and admiration of Williams is staggering.

7

In stark contrast to Ferlinghetti’s idea of branding his authors by shoveling content into templates devoid of personality, Williams wasn’t interested in creating the illusion that he owned every book he published; in other words, the books themselves became active and unique contributors to the Society by the fact of their being in the world rather than byproducts of it. It’s always struck me as ironic that the Beat values espoused in City Lights books (freedom, self-expression, non-conformity, spontaneity, etc.) come in such boring packages. One of the most satisfying things about seeing a bunch of Jargon Society books together is the differences between them. No rules, no template, no formulas, no reruns; each book is built around its content.

8

Williams’s friend, painter Paul Ellsworth is credited with suggesting ‘jargon’ as the name for the private press. He defined “jargon” as his “… own speech. My language, as opposed to the tribe’s language.” Jargonelle is a spring pear indigenous to France, and the OED defines “jargon” as the “inarticulate utterance of birds, or a vocal sound resembling it; twittering, chattering” or “unintelligible or meaningless talk or writing; nonsense, gibberish. (Often a term of contempt for something the speaker does not understand.).” One of the principles Martin Duberman stressed in Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community is that in a community, one loses one’s self while discovering what one means by “self” in the company of others. It was also practical to be a “society” or “organization” in the sixties because it made it easier to obtain nonprofit status, become tax-exempt, and receive support from the National Endowment for the Arts and other sources of funding.

9

From the outset, Olson’s aversion to Patchen and Dahlberg’s projects suggests that if Jargon was a society it was not necessary an idyllic one, nor did the society purport to advance a unified aesthetic or politic. In Williams’s words, if there is any commonality between Jargon’s authors, it is that they are “homemade,” “nonacademic,” “non-urban” writers working on their own terms.

10

James Jaffe put it nicely when he wrote, “The Jargon Society was a reflection of its publisher, its publications the prismatic refractions of his interests and enthusiasms. And yet it wasn’t all about Jonathan, the way so many private presses are all about their printers, whose publications are barely more than a pretext for yet another repetitive expression of their particular aesthetic. After all, Jonathan named it the Jargon ‘Society’ not the Jargon ‘Press.’” Quite unlike other publishers who chose to name their companies after themselves (David Godine; Alfred Knopf; Peter Blum, et al.), Williams’s “society” modestly diffuses the spotlight, illuminating the network of writers, artists, and artisans involved in every book.

11

Williams’s father was also a poet with a lifelong interest in the dialect and vernacular speech of North Carolina. He read Uncle Remus, Porgy, and John Charles McNeill’s Lyrics from Cottonland to him as a child. Lore, dialect and folk culture, particularly that of rural North Carolina where Williams lived most of his life, are as much a part of Jargon’s evolution as is the international avant-garde. Like Duncan, Williams cherished the books of his childhood. Critic Walter Benjamin claims that “… every passion borders on the chaotic,” and cautions bibliophiles, whose passion “… borders on the chaos of memories.” Williams’s library was more than a reflection of his intellectual pursuits; it was a working map of personal history. As a boy growing up in the South, his affinity for writers like H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth brought him to Ben Abramson’s Argus Bookstore, where he stumbled upon James Laughlin’s New Directions books. He henceforth read everything Laughlin was publishing. In 1947, he left his elite secondary school where he worked as the editor of the school newspaper and served as captain of the tennis team to attend Princeton University.

12

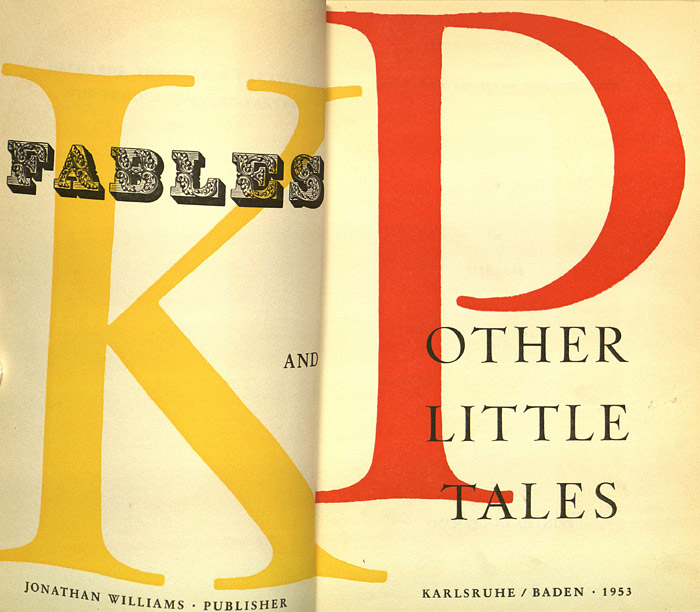

As a student in New Jersey, he read about Patchen’s disability in Miller’s pamphlet Patchen, Man of Anger and Light and decided to contact Laughlin about the ailing writer, then wrote directly to Patchen himself offering to work as a secretary for free. Much to their mutual benefit, Patchen accepted the offer, and Williams went to Old Lyme, Connecticut to spend a month and a half with Kenneth and his wife Miriam. Williams would type for five or six hours a day what Patchen dictated from bed. That manuscript, Fables and Other Little Tales (1953), became the first substantial book published by The Jargon Society (aside from Williams’s self-published titles).

13

Persuaded to some degree by Patchen’s anarchist ideology, Williams tired of his Ivy League surroundings, dropped out during his sophomore year, and headed north to New York City’s Greenwich Village to learn etching, engraving, and printmaking. With a background in painting, a passion for the literature published by New Directions, an ongoing interest in Blake, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and Stéphane Mallarmé, it is easy to see how his interest in publishing really took off when he eventually arrived at the Illinois Institute of Technology to study typography, etching, and photography. It was there that he befriended painter Paul Ellsworth, who became an early collaborator in the spring of 1951 when the two began exploring relationships between words and images. At the time, the Institute served as a haven for Jewish and other refugees from Europe, such as the great designer and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, a former instructor at the Bauhaus, and the Institute’s current director. Williams studied typography under Lorna Zerner who had worked directly with the great typographer and book designer Jan Tschichold. He met potter and radical educator M.C. Richards, then serving as the head of the faculty at BMC, when she came to the institute to persuade students to enroll in a school known as a retreat for “free love, communism, and nigger-lovers.” Signs began pointing back to the South.

14

Unsatisfied with student life in the windy city, Williams confided in his photography professor Harry Callahan, who put him in touch with his friend, Abstract Expressionist photographer Aaron Siskind with whom he planned to co-facilitate a workshop at Black Mountain in the summer session of 1951 (Callahan later asked Siskind to join the faculty at the IIT, which he did, and went on to help establish one of the most innovative centers for the art of the book in America, Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York). After his visit to San Francisco (discussed earlier), Williams enrolled in their summer course, the climate agreed with him, and he signed on for the autumn semester when he would begin studying under Olson.

15

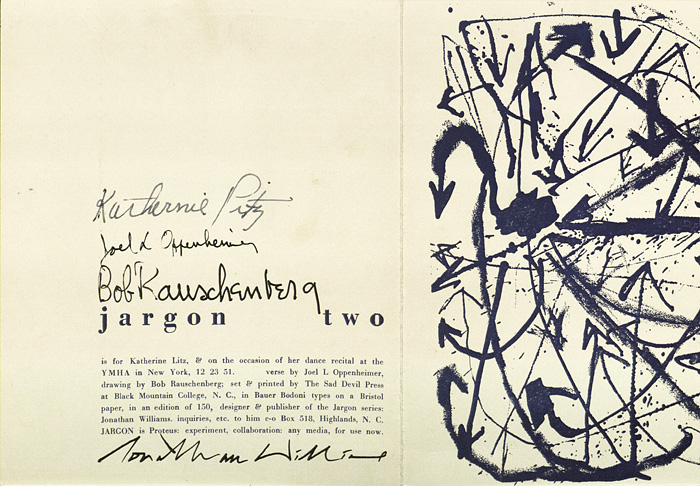

Using the printing press on campus, Williams published the works of other students at the college, including Joel Oppenheimer and Robert Rauschenberg’s collaborative broadside “The Dancer,” his collaboration with Ellsworth, and other student works by Dan Rice and Victor Kalos. Writers Fielding Dawson, Ed Dorn, John Weiners, and the illustrious Francine du Plessix Gray, were also his classmates.

16

Williams’s quixotic days at BMC were cut short by the draft. After numerous attempts to gain conscientious objector status, he had to choose between up to five years behind bars for dodging the draft or the army. He chose the latter, and with the help of a sympathetic chaplain, Williams was transferred from his original post at a rifle company in Fort Knox, Kentucky to Stuttgart, Germany where he worked at a hospital. Shortly after he arrived, he looked up the address of Dr. Walter Cantz, a printer in the city who had worked for Laughlin. Using a small inheritance left to him from a fellow soldier and friend named Charles Neal, he made a decision to take his vision of book publishing to the next level.

17

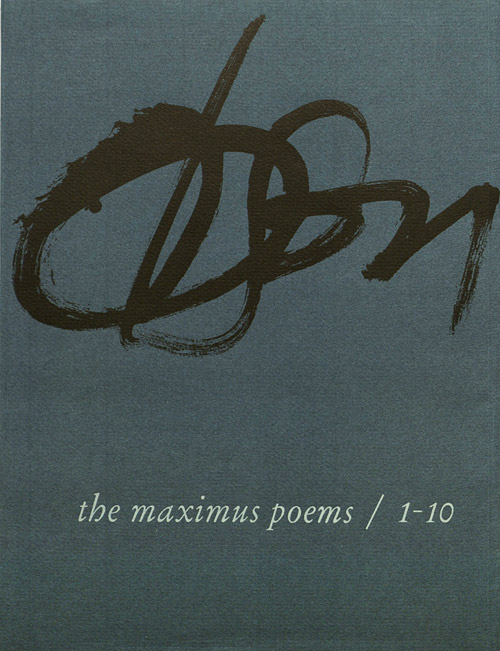

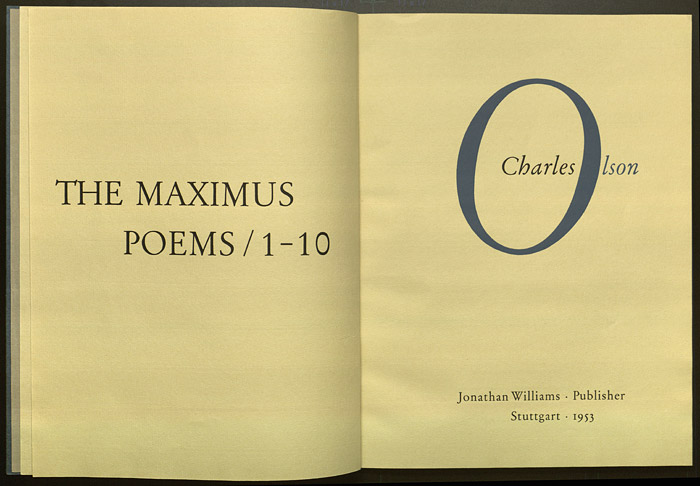

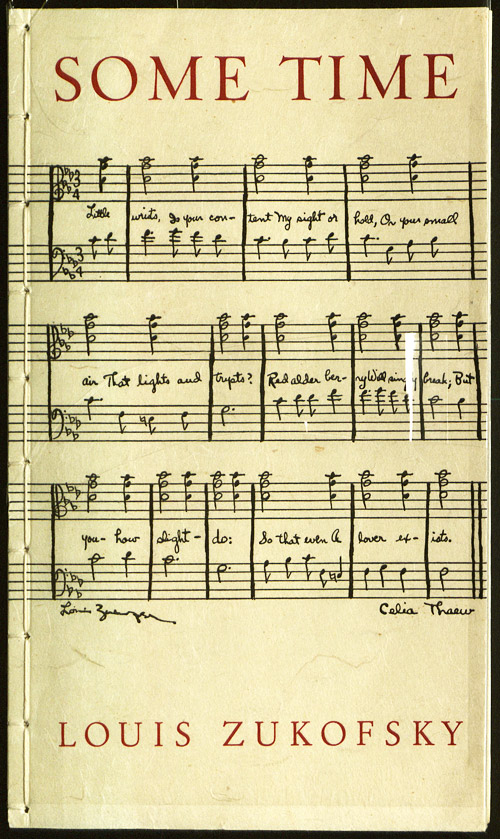

Dr. Cantz’s workshop wasn’t far from the hospital, and Williams’s slight responsibilities afforded him adequate time to work with Cantz and Olson on the first edition of The Maximus Poems I-X (1953) as well as on Louis Zukofsky’s Some Time (1954). Williams’s first book of his own poems, Four Stoppages / A Configuration with graphics by Charles Oscar was printed in another shop across town, while Patchen’s Fables (1953) and Creeley’s early book, The Immoral Proposition (1953) illustrated by René Laubiès, were produced by a printer in nearby Karlsruhr. Without a doubt, these five books form the bedrock of what The Jargon Society was to become, and had Williams chosen never to publish another book, his accomplishments would be more than commendable. Of course, this was only the beginning.

18

Upon return to Black Mountain from Germany, he was delighted to be appointed the College’s publisher, but BMC was bankrupt and about to close its doors forever after only twenty-four years of existence. The early books brought considerable attention to Williams and other emerging ‘outsider’ artists of the era, setting a benchmark for the private press renaissance that began after WWII in America.

19

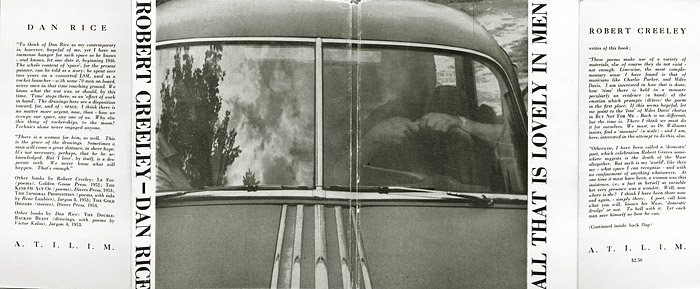

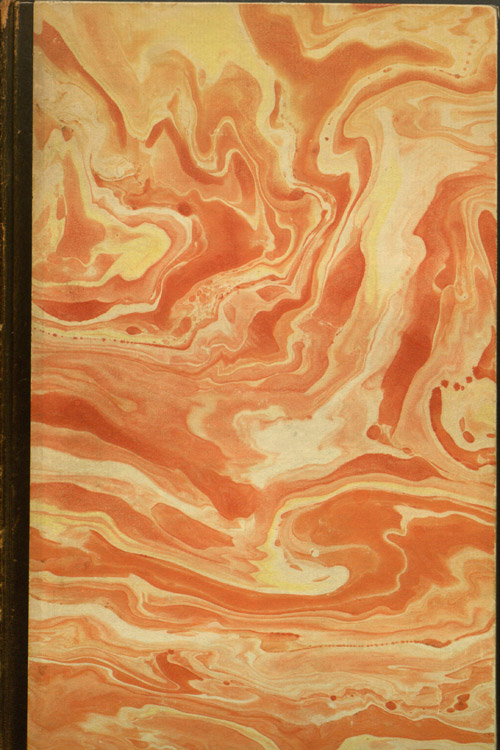

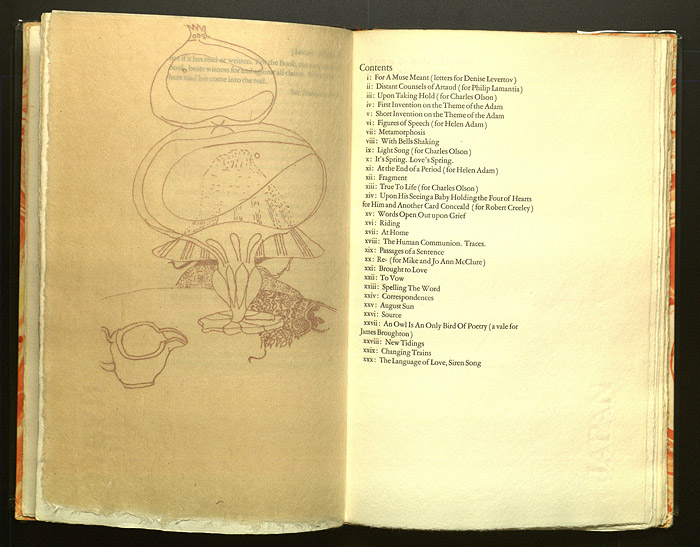

Other landmark books of the 1950s included Creeley’s All That Is Lovely In Men (1955) and The Whip (1957); Duncan’s Letters (perhaps my favorite book from Jargon, designed and printed by Claude Fredericks in 1954); Denise Levertov’s Overland to the Islands (1958); Michael McClure’s Passage (1956); Paul Metcalf’s first book, Will West (1956); Oppenheimer’s The Dutiful Son (1956); three books by Patchen: Fables (1953), Hurrah for Anything (1957) and Poem-scapes (1958); and of course Mina Loy’s Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables (1958).

20

Williams wasn’t a printer, nor so far as I know, did he aspire to be one. This was one clear division between The Jargon Society and most private presses of the earlier half of the twentieth century. When he was starting out, there were artists’ books, but no one would have called them that then. The Jargon Society didn’t print or bind their books on the premises as did private presses of the past. Everything was outsourced.

21

Curiously enough, the design of The Jargon Society books does not reflect the direct influence of the Bauhaus, Swiss, or New Typography in any obvious way, nor do Williams’s photographs resemble those of the Abstract Expressionist, nor do his mature poems appear to be derivative of Olson’s or Creeley’s. Despite his study with an all-star cast of European and American artists, Williams’s aesthetic is singular.

22

Williams boldly calls the shots, and has produced over a hundred titles, including the first books by Lyle Bonge, Peyton Houston, Ronald Johnson, John Menapace, Thomas Meyer, Art Sinsabaugh, and Gilbert Sorrentino. He was also the first to publish the poetry of Guy Davenport and Buckminster Fuller, and responsible for the first American editions of Denise Levertov, Irving Layton and Mina Loy. He brought British language artists Thomas A. Clark, Simon Cutts, and Ian Hamilton Finlay to a new audience. Their influence on Williams’s imaginative bookmaking can be observed in Fourteen Poets, One Artist (poems by Paul Blackburn, Bob Brown, Edward Dahlberg, Max Feinstein, Allen Ginsberg, Paul Goodman, Denise Levertov, Walter Lowenfels, Edward Marshall, E.A. Navaretta, Joel Oppenheimer, Gilbert Sorrentino, Jonathan Williams, and Louis Zukofsky with drawings by Fielding Dawson). Because no two are alike, every book is, in its own way, a collaboration. The editors of Flood Editions have transcribed and published Duncan’s correspondence with Fredericks when they released a trade edition of Letters. This captivating exchange demonstrate that book design, like writing itself, is an activity that requires a great deal of negotiation, revision, and correspondence.

23

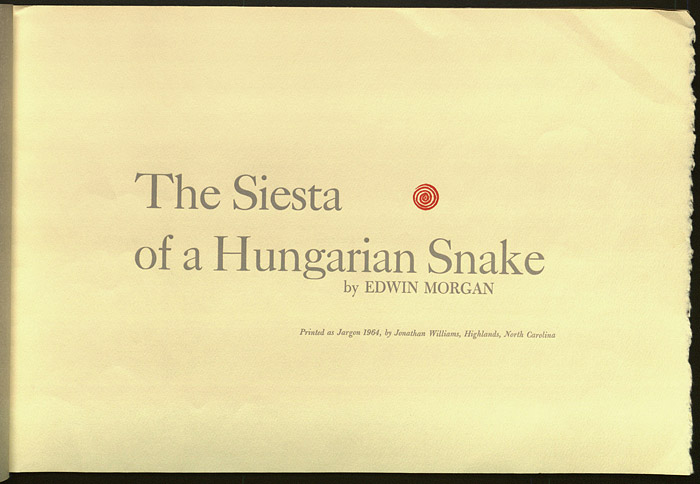

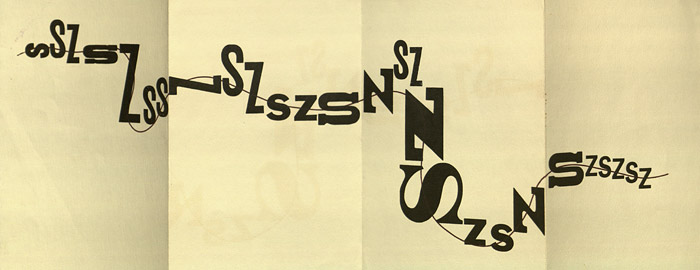

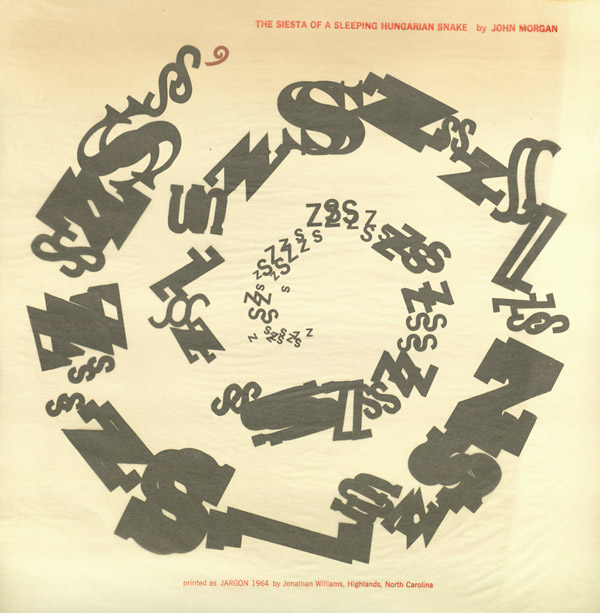

Williams once commissioned Doyle Moore of the Finial Press to design and produce a concrete poem by the Scottish poet Edwin Morgan entitled the Siesta of a Hungarian Snake.

24

Since the book doesn’t have any text, as such, I suspect that Morgan or Williams gave Moore a concept, rather than a manuscript, to interpret and edition with the assistance of his students in the Graphic Design Department at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. The Jargon Society Archive, housed in the Poetry Collection at the University at Buffalo contains five unaccredited mockups most likely produced by students. Communication Design Professor Tony Rozak, a former student of Moore’s, told me that Williams often sent work to Moore, who would in turn bring projects to class. Rozak didn’t remember Morgan’s book in particular, but said that it was the kind of assignment that Moore often introduced to workshops.

25

The largest mockup is incorrectly titled THE SIESTA OF A SLEEPING HUNGARIAN SNAKE by “John” Morgan, “printed by Jonathan Williams, Highlands, North Carolina.” Of course, the verb “printed” should be replaced with “published” because it was Moore and his students who did the actual printing. Part of the jargon that came out of the small press revolution of the sixties was the difference between being a publisher and an actual press operator (and its not just an issue of semantics). For the first time, a publisher who had never seen or operated a printing press could say “I run a press” and be understood, but I digress…

26

In this mockup, one sheet of transparent vellum lays over the poem, printed on smooth cream paper that is both folded and stapled into a black folder. The “poem” or “text” is an instable hodgepodge of Ss and Zs that form the visual-acoustic shape of a snake’s snoozing sound. The second largest mockup features a textured brown cover with a small serpentine spiral. A sheet of vellum covers the handsome title page and the red spiral reappears beside the gray title on deckled cream-colored stock sewn into the cover. Here, the poem is attributed to the correct author, and the colophon, “Printed as Jargon 1964, by Jonathan Williams… ” comes closer to an accurate description of the publisher’s relationship to the printer, but doesn’t quite do the trick. Inside the sSZsZssZSZszS-ZszZSzsZSzszsz recombination is printed on four layers of vellum that are pleasantly disfigured by the minutiae of misalignment between the leaves. The last page is printed in red on heavy cream-colored stock. The title page is grand but overwhelms the tiny text that begs for greater entropy. There is also a smaller version that is quite similar, with two exceptions: the text only appears on one page, and is purposelessly covered by a piece of vellum with a red printer’s device. Like the first mockup, the “S”s and “Z”s are printed in a hodgepodge of fonts strung together by a thin purple line that curves through the slithering letters.

27

The most successful mockup is an accordion fold, but much longer than any of the others. Here the “ZSsz” combination begins in microscopic letters and as the pages unfold, the letters grow larger and larger until they slither (crop or drop) off the page, spiral, and dissolve at the tip of the tail. The title page is printed in blue and black sans serif allowing the tip of the poem to protrude ever so slightly below while the jacket combines an array of energetic wood type in beige with the title in blue running up the body of the “Z” that runs the length of the page.

28

Steve Clay’s Granary Books of New York City and Simon Cutts and Erica Van Horn’s Coracle of Ireland are two of the most inspiring small press operations active in the world today. Jargon’s spirit has moved through dozens, perhaps hundreds of small presses, leaving a living legacy in its wake. In markedly different ways, Granary and Coracle’s own histories blossom, while both pay homage to Williams’s model. To varying degrees, all publishers are cultural sculptors, stone soup alchemists with a taste for the bizarre. The inherent flurry of correspondence between artists, writers, artisans, distributors, critics, readers, and fellow travelers puts the publisher at the center of an ever-widening network of relationships, or as Clay put it in his introduction to When Will the Book be Done? (2001): “The first item that I identify as a Granary Books publication was actually published by Origin Books in 1986 – Wee Lorine Niedecker by Jonathan Williams. It embodies several elements that remain important to me now, some fifteen years later, among which is an acute awareness of the ‘book’ as a physical object. I write this in quotes because the work in question is not a book per se but presents a short poem by Mr. Williams, printed on a small piece of card stock contained within a printed envelope which is enclosed within yet another printed envelope. As such, its references include Williams’ own Jargon Society (‘the custodian of snowflakes’), a press which made ample use of a diverse array of publishing formats including folding cards, broadsides, postcards, pamphlets and books. The Jargon Society was one of two or three publishers which loomed behind the emerald curtain at the fore edge of my imagination as possible exemplars for an entity which had not yet been conceived.”

29

The publisher is responsible for much of the mingling and coordination between parties whose relationships have an unfathomable effect on one another in the present and the course of the future of the arts and culture at large. When I sent Jonathan Williams some of the first books I published at Cuneiform Press nearly ten years ago, he responded with great enthusiasm and praise: it’s always interesting to see what happens when a young publisher gets the bug… there’s no telling how everything turns out.

*According to Susan Finnel Ruff, David Ruff met Jonathan Williams when David was working with Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17 in the Village in the late forties. Probably 1948 or 1949. The same sources also describe Williams meeting Patchen and his wife Miriam in New York and visiting when they were staying in Old Lyme, Connecticut. David and Holly left NY for San Francisco at the end of September, 1950. The Patchens followed and lived with David and Holly until they found a place they could rent and some time after that Jonathan also moved west.

Kyle Schlesinger

Kyle Schlesinger writes and lectures about topics related to poetics, artists’ books and the history of visual communication.