| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 6 printed pages long.

It is copyright © James Jaffe and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/jwd01-jaffe.shtml

Back to the Jonathan Williams Contents list

1

Jonathan Williams died a week ago, on Sunday, March 16th, in Highlands, North Carolina, just past his 79th birthday. Three score years and nearly twenty would be a sufficient span for most lives, and beyond the expectations of most people, but hardly enough for a man of Jonathan’s generous reach. As I’ve come to learn, however, the length of a life isn’t apportioned according to our virtues, or our vices, our accomplishments, or whatever remains of our capacity to make and create; or even our capacity to enjoy ourselves. Life is arbitrary, and it will take you out no matter how much head or heart you have left. Jonathan had both, and, amazingly, a healthy liver, and the odds were still in his favor.

2

I met Jonathan in the early 80s, not long after I started collecting the publications of the Jargon Society, which he began back in 1951, during that legendary Summer Institute at Black Mountain College, where, at the recommendation of Harry Callahan, he had gone to study photography. It was at Black Mountain that he met Creeley, and Dawson, and Duncan, and Olson, and Oppenheimer, to mention only a few of the poets whose books he would soon publish. Jonathan eventually tired of talking about Black Mountain, but it’s where he got his big push.

3

Jargon 1, Jonathan’s Garbage Litters the Iron Face of the Sun’s Child is dated June 25, 1951. Jargon 2, Joel Oppenheimer’s The Dancer, with a drawing by Robert Rauschenberg, was printed for a dance recital by Katherine Litz at the YMHA in New York on December 23, 1951, but by December 17th, Jonathan was mailing a copy from Highlands to his best friend from St. Albans, Stanley Willis. The Dancer notes that “JARGON is Proteus: experiment, collaboration: any media, for use now.” That was Jonathan, and Jonathan stuck to that creed his whole life, non-stop, until infirmity finally brought him down.

4

When Jonathan caught wind of my interest in him, he asked me to join the board of the Jargon Society, and before I knew what hit me I was driving down to Winston-Salem for the annual meeting. I don’t know what Jonathan was thinking; no doubt that I had money, and that I could be of use. Perhaps he thought I would become a patron, a benefactor, another generous soul who would support him and his good works, who would help him make all the things he wanted to make, just the way he wanted to make them, so that the rest of the world — or as many of them as had the propensity to find them — could discover them, too. Or maybe he was just curious, and wanted to meet a new collector who had taken such a keen interest in him and the Jargon Society.

5

At the time, I only knew Jonathan through his works, but to me, they were marvelous, every last one of them. I’d spread them out where you could see them, and they dazzled me. They were more varied than the publications of any other “private press”, and although each one was different — unique and curious in its own way, never uniform — they were all unmistakably the work of this one extraordinary man; and all of them were as personal and personable as he turned out to be. I wanted to meet Jonathan as much as I wanted to own all of the books he’d written or published. And it was spring, and spring is the best time to be on the road heading south.

6

Jonathan wasn’t a “fine printer”, and the Jargon Society wasn’t a fine press in the traditional sense. Jonathan wasn’t derivative or devotional; he wasn’t a disciple; and although a collector, he wasn’t interested in books no one reads. He didn’t aspire to be a craftsman; he didn’t print the books himself, and he certainly had no desire to set lead type on a hand-press all day. There was nothing hermetic about Jonathan; however rusticated he may have appeared at times. He wanted to make things happen.

7

The Jargon Society was a reflection of its publisher, its publications the prismatic refractions of his interests and enthusiasms. And yet it wasn’t all about Jonathan, the way so many private presses are all about their printers, whose publications are barely more than a pretext for yet another repetitive expression of their particular aesthetic. After all, Jonathan named it the Jargon “Society” not the Jargon “Press”. It wasn’t about putting his stamp, his signature, on everything. And as such the Jargon Society differed from other literary private presses in being radical and democratic, in giving each book its own identity, its own idiosyncratic form. Jonathan never sacrificed a book, or its author, to a single concept. He didn’t identify himself or his books with a favorite format or formula. Jonathan’s books don’t all look alike anymore than the poets he published looked alike. For all their affinities, the books Jonathan published were allowed to be as individual and independent as he was himself.

8

Whether Jonathan found them, or they found Jonathan, one way or another, Jonathan knew more interesting people than anyone I ever met. Miraculously it seemed to me, he even knew “the deliciously named V. E. G. Ham”, one of the most brilliant and entertaining undergraduates at Sewanee while I was there. It turned out that Gene (Van Eugene Gatewood Ham) was a cousin of the wife of a friend of Jonathan’s in Kentucky. But it figured that Jonathan would have known Gene. Jonathan had a knack for knowing remarkable people. It seemed he could put his ear to the ground, or cock his head to the wind, or just open the morning’s mail and something original would come to hand. Jonathan had a nose, a sharp eye, and he paid attention; he discerned and distinguished the ordinary from the extraordinary; and unselfishly, he spread the word.

9

Jonathan always had more ideas than he could realize, and he never seemed to run out. There were plenty of books that should have been done, but couldn’t be done without big grants or generous contributions from friends, most of whom realized that their contributions were supporting him as well as underwriting the costs of the books. Some books were simply too expensive for him to produce himself — like the monograph on the photographs of Art Sinsabaugh that Jonathan had envisioned and hoped to publish nearly forty years ago, but that was finally published by someone else in 2004 , and I suspect, not as well as Jonathan would have done it.

10

There are more than a few libraries around the country waiting for books that Jonathan announced a long time ago but was never able to publish, wonderful books that would have enriched our lives, if only Jonathan had been able to find the money. Books like The Selected Poems of Bob Brown, designated Jargon 34; or The Selected Poems of Mason Jordan Mason (Judson Crews), slated to be Jargon 54; or Eyes in Leaves: A Tribute to Guy Davenport, which was planned — in the 70s! — as Jargon 90. The problem was — the problem always is — that most people with money want to use their money to make more money; they don’t want to make beautiful things that don’t make money — like books. Jonathan took a loss on almost every book he published, but it didn’t stop him.

11

Jonathan cared about making good books and making them right; and he didn’t much care whether they sold or not. He didn’t expect much from the public, and would have agreed with Oscar Wilde that “The public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything, except what is worth knowing.” Jonathan had his own vision, his own tastes, and his own standards, and he lived by them. He would seldom compromise, even if it meant that a book he dearly hoped to make wouldn’t be done, even when it was a book he himself had written, like his book on Southern outsider art — the book as he wanted it to be, not the book that was eventually published. When it came to books and life, Jonathan knew what he wanted to do, and how he wanted to do it. And he did it, obstinately, and beautifully, whenever possible.

12

Jonathan peddled his publications, too – in person – starting in the 50s after he returned from Germany where he had served as a conscientious objector. [On second thought, I have a black-letter poster for a reading he gave there, and I’d be willing to bet that he started selling books while he was in Germany.] Jonathan would drive his VW bug around the country, giving poetry readings and trying to sell those beautiful “classic” Jargon publications: Creeley’s The Immoral Proposition (1953) and All That Is Lovely In Men (1955); Duncan’s Letters (1954); Olson’s The Maximus Poems (1953-1956); Levertov’s Overland to the Islands (1958); McClure’s Passage (1956); Oppenheimer’s The Dutiful Son (1956); three books of Kenneth Patchen’s: Fables (1953), Hurrah for Anything (1957) and Poem-scapes (1958); Zukofsky’s Some Time (1956); and of course Mina Loy’s Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables (1958).

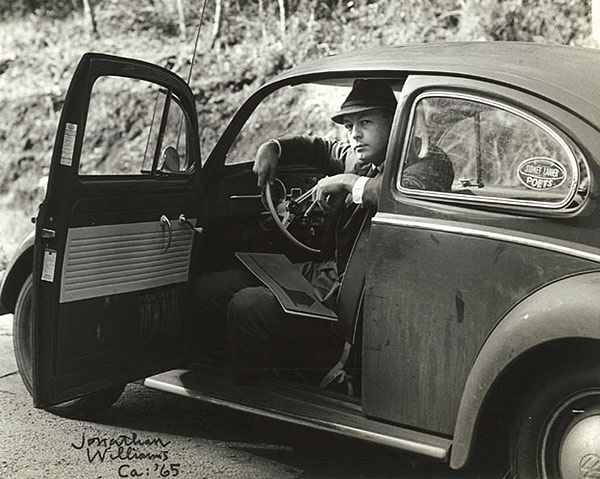

Jonathan Williams, circa 1965.

13

I have a photograph of Jonathan sitting in his VW bug in the mid-1960s, with a copy of Sherwood Anderson’s Six Mid-American Chants (1964), illustrated with the panoramic mid-western photographs of Art Sinsabaugh on his lap. Jonathan was only 35 years old. Fifteen years later, a collection of photographs called JW, on the Road Selling that Old Orphic Snake-Oil in the Jargon-sized Bottles, 1951-1978 (Visual Press, 1979) was published to commemorate Jonathan’s 50th birthday. Jonathan was still at it, going strong, although by then he was driving a VW Rabbit – Diesel.

14

The wonder is that Jonathan was able to accomplish so much as a publisher; the pity is that he wasn’t given the means to do more. Jargon’s publications are a perpetual testament to Jonathan’s desire to make things of worth, and to introduce worthy poets and artists to the world. Many of them are breath-taking examples of what Jonathan was able to do with modest means, determination, and self-sacrifice. Over the years, more than a few beloved books and photographs were sold — at disadvantageous terms — in order to subsidize the next Jargon publication, to make the next project possible, or just to pay the household bills.

15

What Jonathan did with what he was given was prodigious, and I’ve been talking only about Jonathan the publisher. Jonathan’s publications represented only a fraction of what he did and what he might have done had he been given the time and the money to realize his ideas. In addition to being a publisher, he was an endlessly inventive poet, a brilliant photographer, an early champion of some of the best modern photographers — Clarence John Laughlin, Aaron Siskind, Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Frederick Sommer — not to immediately mention some of the other wonderful photographers he introduced me and many others to: Raymond Moore, Guy Mendes, John Menapace, Elizabeth Matheson, David Spears. Jonathan was also one of the earliest, most prescient, and least exploitative exponents of Southern outsider art.

16

Jonathan also had a rich and full personal life – perhaps more than one when you consider that he lived half the year in Highlands, NC, and the other half in Cumbria, England. And it was a life that Jonathan shared, as he shared himself, his wit, his humor, his sense of friendship and conviviality. Looking at all the occasional postcards, letters, ephemeral publications, even solicitations for money for the Jargon society that Jonathan created in so many myriad forms for over forty years, I doubt that a day passed without Jonathan sending something to someone, something unique and irrepressibly enlivening. It was a wonderful life, carefully made more gracious and hospitable by the poet Thomas Meyer, Jonathan’s wise and irreplaceable partner of forty years. It was as enviable a life as one could imagine, and almost unimaginable in today’s cannibalistic world.

17

To put it plainly, Jonathan was the most civilized man I ever met, notwithstanding his distaste for Bach; and the times I spent in his company, at his family home in Highlands or the cottage at Corn Close, have been among the most memorable and nourishing experiences of my life. And when it was time to leave, Jonathan always gave you a push in the right direction. My son will remember our ploughman’s lunch at the Shepherd’s Inn in Melmerby long after I’m gone, and he’ll always remember Jonathan, who told us to go and showed us the way.

18

We were fortunate to have Jonathan as our guide. We’ve all been fortunate to have Jonathan as our guide.

19

When I heard that Jonathan had died, I wrote to Peter Howard at Serendipity Books in Berkeley. I thought he would want to know. Peter’s response was worthy of Peter, and worthy of Jonathan, whose obituaries for his own friends are the finest of their kind. I can’t imagine a more fitting tribute: “I met him only once, on the hustle for money for a book, but I knew all along his publications were the most remarkable of any in the USA in his lifetime. Early for the writer, always beautiful. Who can always be first and always beautiful?”

20

As it turned out, during the nearly twenty-five years I’ve known Jonathan, I built my collection, I became Jonathan’s bibliographer and published a checklist of his work; I published his correspondence with Guy Davenport; I was of some use. All in all, I managed to do less than I might have done, or than Jonathan might have expected of me. Like so many others who knew Jonathan, I got far more than I ever gave. And for that I will always be grateful.

21

Amen. Huzza. Selah.

James Jaffe is a bookseller specializing in literature and art, manuscripts, letters, and archives. He is also the publisher of A Garden Carried in a Pocket: The Letters of Jonathan Williams & Guy Davenport, 1964-1968. A photographic portrait of Corn Close, JW’s cottage in the Yorkshire Dales, is in the works. This essay appeared on Jaffe’s blog after Jonathan’s death. Website: www.jamesjaffe.com