| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Ángel Escobar Estate and Kristin Dykstra and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/escobar-poems.shtml

[»»] Also see Pedro Marqués de Armas: The great leap outward:

On the life and poetry of Ángel Escobar, in this issue of Jacket.

Hospitals

I saw Rimbaud roped to a bed

and the Paterprotagonist roping him down hard,

and his pajamas, letting him go, they roared and

his smallest innocent bones came loose with doctors

blowing on that broken bassoon,

the glasses shattered, and the blinds, and the symbols

then to each according to his symptom

they gave his dose, his eyes, his Lenten discipline.

It was March in leap year and I saw

the goat choking on a piece of rock.

Big black bird, scapegoat exploiting his enclosure, and he sat there

looking upwards—

the responsibility and blame to the telephones,

to the old ways of the judges

and their children. I saw Rimbaud spitting

into a basket of eyes well tempered

and wholesome as needles. I saw him “I do not

repent.” I am composed, I am

the scribe, the ox

who has not owned a thing. I am composed.

Hospitales

Yo vi a Rimbaud amarrado en una cama

y al Papá Protagónico amarrándolo duro,

y su piyama, soltándolo –gritaban y se soltaron

los huesitos vírgenes con doctores soplando

el fagot roto,

se quebraron los vasos, las persianas, los símbolos

y luego a cada cual según su síntoma

le entregaron su píldora, sus ojos, su cuaresma.

Era el año bisiesto de estos días de Marzo y vi

como se ahorcaba el chivo en un pedrusco.

El choncholí explotando su cercado, y él sentado

mirando por arriba—

responsabilidad y culpa a los teléfonos,

a los viejos modales de los jueces

y a sus hijos. Yo vi a Rimbaud escupiendo

en una cesta de ojos bien templados,

y sanos como agujas. Lo vi “No me

arrepiento”. Estoy tranquilo, soy

el escriba, el buey

que no ha tenido nada. Estoy tranquilo.

— Spanish originally published in Abuso de confianza (1992)

The chosen one

Above this stone is my head.

And above my head is the moon.

That knowledge makes no one feel better.

Much less the knowledge that above the moon

there are another head and another stone.

And that the sum of acts and words

I’ve performed may end here.

In another head, another stone and another moon,

which are neither close nor far

which we once would mention in apathy and vanity.

This does not divide me from my destiny:

The day, the night, the animal and the line.

Moreover, what curve infinitude exists where

the head is the stone and the stone

is the moon. Moons, heads, stones

are not consecutive sets. Or

the facets of my face in the lake.

I know: only the crackles in which I burn follow upon each other.

I know: only my discourse is given to the spectacle.

And: each one of these propositions

renders the heads, stones

and moons of the elders useless. And I know

someone else’s conclusion will render my own

useless. Today all archetypes are empty.

I no longer need justification

among symbols. I am going to die.

My body is just a body squatting.

The white esplanade and the blade

know nothing. Their interchangeable

combination of reasons pulsates through me.

They were not the sharp edge or extension, merely

something awaiting me here. None render me invulnerable,

not the steps or the contact, not those hot coals,

the pleasures of walking and seeing and touching and speaking well.

They can’t fend off the torches or this final hour.

Only I know my name, only I know

obsession with a number. –They seek and locate

name and number the center contains no more than

other names and numbers and eclipses.—

They slay me. As if I were some other.

My blood will run into voracious

clots, lumps I swore in jest were

presages of the blades.

Now they are the blades. There’s no jest

or oath that has not also been the jest

and oath signing my death.

To all this ceremony they give the name

sacrifice. Ah, I too picked through

the fish of days, sums

and nomenclature. I saw

images too quick for dream.

I intuited an order that wasn’t abstinence.

I was the lowest. I was the totality.

Or so I believed I intuited saw and existed. Now

my body is just a body where light

and shadow clash and it’s over and don’t come back.

But among candles and eyes I look and burn.

I am what I was. I am what I will not be.

I exist as excessively arduous realities:

Moons, heads, stones, ceremonies.

I don’t want to know they escape, don’t want to know how

things went sneaking off from their names.

I will tell lies, lie as one lies to oneself:

“They’re right here. Here, alien to me.”

No. I am the alien. Nor does it give joy

to imagine that my death was written,

that someone in his own space, unhurried, reads:

“The quick arrow has already forgotten the bow.

It doesn’t know if there’s one last inconsistency:

Slip, splendor, mask or object.”

It is my death. My death. That is my death.

All comes to an end. Oh, no. Ah, pyramid. Ah, moon.

The spiral goes on. The circle goes on.

And so what if, spiraling and circling, I burn out.

They arrive. They’ll make it. I, the chosen thing. No longer an exception.

Or a norm. They anchor me. Everything I once feared

shrouds me. Everything I desired takes me in.

Insolence, dread, yearning, error arrive,

present as this white and obstinate day

among all the days. They are the blade’s meticulous

slit. They are this dark border and this

enclosure where the most arduous thing of all is

the inability to get away from knowing.

El escogido

Sobre esta piedra está mi cabeza.

Y sobre mi cabeza está la luna.

Saber eso no reconforta a nadie.

Menos aún saber que sobre la luna

hay otra cabeza y otra piedra.

Y que la suma de actos y palabras

que he cometido terminaran aquí.

En otra cabeza, otra piedra y otra luna

que no son ni estas ni aquellas

que por desidia y vanidad mentábamos.

Esto no me separa de mi destino:

El día, la noche, el animal y el límite.

Hay además qué corva infinitud donde

la cabeza es la piedra y la piedra

es la luna. Lunas, cabezas, piedras

no son conjuntos sucesivos. Ni son

las caras de mi cara en el lago.

Sé que sólo los ruidos en que ardo se suceden.

Y que sólo mi discurso es dado al espectáculo.

Sé que cada una de estas proposiciones

vuelve inútiles las cabezas, las piedras

y las lunas de los mayores. Y sé

que la conclusión de alguno inutilizará

las mías. Hoy todo arquetipo es vano.

No necesito ya ninguna justificación

entre los símbolos. Voy a morir.

Mi cuerpo es sólo un cuerpo acuclillado.

Nada saben ni la blanca explanada

ni el cuchillo. Sólo por mí repiten

su intercambiable suma de razones.

No eran el filo y la extensión, sino sólo

lo que aquí me esperaba. Ni los pasos ni el tacto,

ese rescoldo, el gusto de caminar y ver

y tocar y bien decir me hacen invulnerable.

No evitan las antorchas ni esta última hora.

Sólo yo sé mi nombre, sólo yo sé

de la obsesión de un número. – Buscan y hallan

nombre y número el centro en donde no hay más

que otros nombres y números y eclipses--.

Me matan. Lo hacen como si yo fuera otro.

Mi sangre topará con los terrones

filosos que jugando juré que eran

la prefiguración de los cuchillos.

Ahora son los cuchillos. No hay juego

ni juramento que no hayan sido el juego

y el juramento que ahora signan mi muerte.

A toda esta ceremonia la llaman

sacrificio. Ah, yo también hurgaba

entre los peces de los días, las cifras

y las nomenclaturas. Yo también vi

imágenes demasiado veloces para el sueño.

Intuí una orden que no era la vigilia.

Fui lo ínfimo. Fui la totalidad.

O creí intuir y ver y ser. Ahora

mi cuerpo es sólo un cuerpo en el que chocan

luz y sombra y se acabó y no vuelvas.

Pero entre candelas y ojos miro y ardo.

Soy lo que fui. Soy lo que no seré.

Soy realidades excesivamente arduas:

Lunas, cabezas, piedras, ceremonias.

No quiero saber que huyen, no quiero saber cómo

las cosas a hurtadillas se escapan de sus nombres.

Voy a mentir, voy a mentir como se miente:

“Están ahí. Y ahí me son ajenas.”

No. El ajeno soy yo. Tampoco alegra

imaginar que acaso mi muerte estaba escrita

y que alguien, en su lugar, parsimonio, lee:

“El fugaz dardo ya se olvidó del arco.

Desconoce si hay un capricho más:

Desliz, esplendor, máscara u objeto.”

Es mi muerte. Mi muerte. Esa es mi muerte.

Todo se acaba. Oh, no. Ay, pirámide. Ay, luna.

Continúa la espiral. Continúa el círculo.

Y qué, si en espiral y círculo me apago.

Vienen. Lo harán. Yo, lo escogido. Ya ni excepción.

Ni norma. Me aferran. Todo lo que temí

me envuelve. Todo lo que anhelé me acoge.

Insolencia, pavor, anhelo, error acuden.

Son este blanco y terco día entre

todos los días. Son el minucioso tajo

del cuchillo. Son esta franja oscura y son

este recinto donde lo más arduo es

no poder escapar del conocimiento.

— From Abuso de confianza (1992)

Holdings

The deadly one is the kestrel.

I wanted to eat a Chinese orange with

Sunangel, or to see,

at her side, leaves on a French lemon tree;

I want her to see a cactus

on an uneven rectangle of Mexican earth –;

I want to be a weeping willow that brings her joy,

or a bitter melon or familiar flowering stock;

I’d walk with her among the birches

I saw first in a film, and later in Moscow—;

we’d do many things by a eucalyptus tree

or in a forest of eucalyptus;

I want to think of purslane, cilantro,

of an apple or two pears, and a mango in my hand:

it all brings Sunangel to mind –

as do oregano, bougainvillea, China rose

and the shredders at El Caney de las Mercedes—;

Sunangel rejoices when plants send out their shoots –

even if the shoots are fantasies in this barren hospice,

and if here, close by, a friend sees a bluish light,

another may already be dead, deader than a deathmask,

lime and asbestos burn unseen,

and everyone who used to trample me folds like gloves

when the merchants and money arrive,

the golden stretchers, resort hotels sited between

the line of mountains and the fear, on the dark grassland

where perhaps no triton presently rules.

Sunangel, in my memory, laughs in spite of everything.

But the kestrel is the deadly presence – up there, flying

above prescribed ideas

that shelter the suicidal.

Haberes

Lo fatal es el cernícalo.

Yo quisiera comerme con Solángel

una naranja de China, o ver,

junto a ella, las hojas de un limonero francés;

yo quiero que ella vea un cactus

en un rectángulo áspero de tierra mexicana –;

yo quiero ser un sauce llorón que a ella le guste,

o el cundiamor o el alhelí de siempre;

me pasearía con ella por entre los abedules

que vi en un Cine de Arte primero que en Moscú—;

cuántas cosas haríamos junto a algún eucalipto

o debajo de un bosque de eucaliptos;

quiero pensar ahora en la verdolaga, en el cilantro,

tener una manzana o dos peras y un mango:

todo eso me recuerda a Solángel –

también el orégano, la buganvilla, el marpacífico

y los mayales del Caney de las Mercedes –:

Solángel ríe cuando brota todo lo vegetal –

aunque este brote sea un sueño en este hospicio estéril,

y aquí, cerca, un amigo vea una luz cianótica,

y otro esté muerto ya, más que una máscara,

y la cal y el amianto prendan un leño ciego,

y todos los que me pisotean transijan como guantes

cuando llegan los mercaderes y el dinero,

las parihuelas de oro, los hoteles soplados

entre la cordillera y el espanto, en la oscura pradera

donde no hay ni un solo tritón que esté reinando.

Solángel, en la memoria, ríe a pesar de todo.

Pero lo fatal es el cernícalo – aquél, uno

que vuela sobre esas ideas fijas

que alientan al suicida.

— Spanish originally published in El examen no ha terminado (1997)

Kristin Dykstra thanks the Banff Centre (Alberta, Canada) for supporting her work on these translations, as well as Ana María Jiménez for her permission to publish the poems.

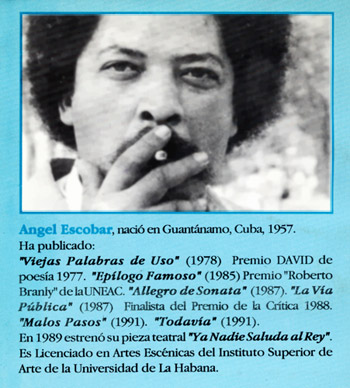

Ángel Escobar, author photo. Back cover of original Chilean edition of Abuso de confianza (Santiago, Kipus 21 Editora, 1992). The book was subsequently reprinted in Cuba.

Ángel Escobar Varela was born in Cuba’s eastern agricultural province of Guantánamo in 1957. He took two university degrees in theater arts, and he soon won a national prize for emerging writers with his 1977 poetry collection Viejas palabras de uso. Escobar went on to compose numerous other books of poetry: Epílogo famoso (1985), La vía pública (1987), Malos pasos (1991), Todavía (1991), Abuso de confianza (1992), Cuando salí de La Habana (1997), El examen no ha terminado (1997), and La sombra del decir (1997). He took his life by jumping off a building in Havana in 1997. Ediciones UNIÓN of Havana published his collected poetry in 2006 as Ángel Escobar: Poesía completa.

Kristin Dykstra

Kristin Dykstra’s translations and commentary are featured in bilingual editions of poetry by Reina María Rodríguez and Omar Pérez, including the recent Something of the Sacred / Algo de lo sagrado (Factory School, 2007). Her work has appeared recently in The Brooklyn Rail, Circumference, Afro-Hispanic Review, Words without Borders, The Whole Island, The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry, and other journals and anthologies. Her translations of poems by Ángel Escobar have been supported in part with a residency at the Banff Centre. She co-edits Mandorla: New Writing from the Americas / Nueva escritura de las Américas.

Ángel Escobar’s work is embraced today by Cuban readers living both on and off the island, as well as an increasing number of Spanish-language readers from other countries. Translations are now beginning to appear in English.

Poems by Ángel Escobar at The Brooklyn Rail / InTranslation, June 2009 (tr. Kristin Dykstra)

http://intranslation.brooklynrail.org/spanish/poems-by-angel-escobar

Poems by Ángel Escobar at Alligatorzine 33 (tr. Mónica de la Torre)

http://www.alligatorzine.be/pages/zine33.html

Some translations of Escobar’s poetry into English are now available in print, with more forthcoming.

Mandorla: New Writing from the Americas / Nueva escritura de las Américas 11 (2009). Dossier dedicated to Escobar with critical commentaries in English and Spanish, as well as 22 sample poems in each language. For more information see www.litline.org/Mandorla

The Whole Island: Six Decades of Cuban Poetry (University of California Press, 2009). For more information about this extensive anthology, see the UC Press page for the book: http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/10708.php

Circumference: A Bi-Annual Journal of Poetry in Translation (forthcoming). For more information see http://www.circumferencemag.com/

Lana Turner: A Journal of Poetry and Opinion (forthcoming). For more information see http://lanaturnerjournal.com/