| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/r-boykoff-sand-rb-metres.shtml

Jules Boykoff and Kaia Sand

Landscapes of Dissent:

Guerrilla Poetry & Public Space

reviewed by

Philip Metres

(Palm Press, 2008). Paper. 128 pages. $15.00 ISBN: 978-0-9789262-4-3 0-9789262-4-2

This review is about 5 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Philip Metres and Jacket magazine 2009.

See our [»»] copyright notice.

1

The cover of this provocative and insightful primer on the theory and praxis of “guerrilla poetry” features a blued photographic image of graffiti, the most visible of which is the stenciled command “VOTE OR DIE!” on what looks like a concrete garbage receptacle. But “VOTE OR DIE” is the trigger to two other pieces on the receptacle: a tagged/scrawled “Revolt,” and a scraped “NOW WHAT?” In a sense, these three iterations of graffiti — in their semantic and material meanings — suggest the breaths and breadths, the quests and questions, of guerrilla poetry. Though we begin with the (mainstream) command to vote, lest the consequences be dire, these guerrilla commentators ask what happens after one exercises that right to use one’s voice (“vote,” after all, comes from vocare, to speak). “Now what,” indeed, in the wake of the election of the great liberal hope, Barack Obama. “Revolt”? But how?

Paragraph 2

In the new Obama age, where web activism and organizing reached a new level of sophistication, this little conversation on a public garbage can could not be more timely. There is little doubt that web organizing gave Barack Obama an enormous boost at the polls, and brought organizers, activists, and enthusiastic new voters out onto the streets and into the polling booths.

Still, just the other day, I walked down a main street in town, and nearly every person I passed was wearing ear buds or talking on the mobile phone; these digital natives seemed only to haunt the public sphere that they traversed, creating their own spheres in which they moved alone.

3

We live in an historical moment where both poetry and political activism in hyperspace have developed enough to reveal hyperspace’s possibilities and limits. On the one hand, the development of the digital network increases what David Harvey calls the “space/time compression” and offers the possibilities of a global subjectivity responsible both to the local and to the global. On the other hand, relatively unfettered by local or national bonds, this digitized virtual realm is also accessible only to the privileged few. While we network ourselves into online digital communities, and cast off laptops every few years, someone in the Third World sits among toxic metals, recycling what he can, the chemical wastes poisoning his water supply. At the risk of sounding like an apocalyptic Luddite, I fear that “The Matrix” looks less and less like science fiction: to quote Zizek quoting the rebel who gestures over a smoking, ruined landscape: “welcome to the desert of the real.”

4

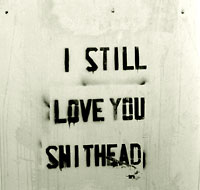

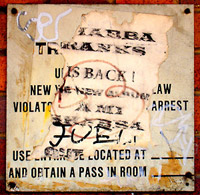

Landscapes of Dissent provides a forceful reminder of the critical need to reclaim public space as a site of political action, symbolic exchange, and collective being. In the words of geographer Don Mitchell, “public spaces are decisive, for it is here the desires and needs of individuals can be seen, and therefore recognized, resisted, or… wiped out.” (7). Drawing upon the theories and practices of poets engaged in articulating and building a poetics in and of public space, Landscapes of Dissent offers itself both as a microsurvey of guerrilla poetry in the avant-garde tradition, and a how-to manual for future deployments of such locational verse. Accompanied by photos documenting guerrilla poetics in action, the book makes participating in such homespun actions seem more than possible — it makes them seem inviting and necessary.

5

Landscapes of Dissent makes a critical intervention in a now-developing interdisciplinary inquiry about the politics and poetics of dissent, exploring not only what dissent might look like when framed and made by poets, but also how dissent alters our understanding of what poetry might be and become. In the conclusion to an investigation of war resistance poetry, Behind the Lines: War Resistance Poetry on the American Homefront, I also called for a poetry that breathed outside of the confines of the book, and for us to see poetry freed into the third dimension of public spaces: “war resistance poems thus ask for our redeployment in multiple sites, returning poetry to where it thrives — at the local and in local resistance [i.e. “behind the lines” and beyond the page and into the public square] — as graffiti, in pamphlets, as performances, as songs, and in the classroom” (233). A year after the publication of Behind the Lines, as I wrote in “Lang/scapes: Further Explorations of War Resistance Poetry in Public Spaces,” I found many

6

signs that war resistance poetry is hardly moribund — and often lives in the form of signs themselves: hijacked billboards, scrawled bedsheets, homemade placards, spray-painted bullets of compressed language suddenly visible in landscapes usually denuded of poetic speech-acts… On faculty office doors, in secluded parks, at peace shows, in poetry readings in reading halls and on the streets, later YouTubed for the Internet masses, above freeway overpasses, on roadside fences — war resistance poetry has laid claim to spaces typically reserved for advertisements and safety signs, sutured the space between the public sphere and the literary sphere… to give voice to the growing weariness and outrage at the Iraq War — a war initiated through falsified evidence, conducted with arrogant short-sightedness, and criminally mismanaged.

7

Landscape’s particular intervention into this conversation is to establish first a theoretical framework, using theories of geography and public space, by which to valorize the work of what they call “guerrilla poets” — poets operating on the edges of (or against) the law, whose page is public space itself, and whose readership is anyone who traverses those spaces. In contrast to Jurgen Habermas’ idealized notion of the “public sphere,” Landscape co-authors Jules Boykoff and Kaia Sand — both notable poets themselves, both on and off the page — note the criticism of a public sphere “rooted in reconciliation and unity which surreptitiously blunts the sharp edges of difference and inequality” (14) and embrace Nancy Fraser’s notion of “subaltern counterpublics” (14). Amid the thicket of laws that govern and curtail free expression, guerrilla poets negotiate ways to appropriate public space from strictly commercial or privatized interests, and attempt to render visible “the sharp edges of difference and inequality.”

8

By acknowledging but bracketing off of conceptual installations and public poetry projects, Boykoff and Sand can focus on and celebrate four case studies of more ephemeral, more politically radical work, which engage an inadvertent audience that neither expects nor necessarily welcomes their encounters: PIPA (Poetry is Public Art), PACE (Poet Activist Community Connection), the Agit-Truth Collective, and the Sidewalk Blogger. From the poetics and politics of grief articulated by PIPA in their “Debunker Mentality” posters after the attacks of September, to the performative flyering of the Philly-based PACE; from the road sign actions of the Agit-Truth Collective a la Burma Shave that gave rise to temporaryautonomouszones (TAZ), to the acerbic postered commentaries by the Sidewalk Blogger in Hawai’i; these guerrilla poets turn long-standing modes of advertising and political activism into acts of politico-poetic subversion, and, in their fugitive moments, stage for citizens momentary acts of frisson and cognitive dissonance.

9

Together, despite their different manifestations of “guerrilla poetry,” these projects share a common concern for a poetic practice that draws upon the genealogy of both the avant-garde and contemporary critical theory, and stake a claim against the pronouncements of the “resistance is futile” line of postmodern theory. Indeed, many of these poets apparently emerged from poetics programs constellating around former L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poet-provocateurs Bob Perelman and Charles Bernstein; in the relatively small world of experimental poetry, many of their names are familiar from the post-language generation: Kristin Prevallet (PIPA); Linh Dinh, CA Conrad, Mytili Jagannathan, Frank Sherlock (PACE); Jules Boykoff, Kaia Sand (Agit-Truth); and Susan Schultz (the Sidewalk Blogger). (Perhaps a more exhaustive examination would show other activist movements and other poetry communities have participated in their own versions of “guerrilla poetics.”)

10

For these groups, as for Boykoff and Sand, the language of resistance, and resistance through language, is fertile — insofar as it is generative, insofar as it renders visible the voices that the presiding national narrative has repressed, insoar as it engenders its own actions and reactions. In their words:

11

We are surrounded by language in our landscape. If we consider our streets as pages, as Heriberto Yépez suggests, we also encounter this fact: the book is mostly written. Public poetry projects face these conditions: how might one’s inserted language interact with what’s already there? How do we, passersby walking the streets and shopping in stores, make meaning from this extant language? In our various ways, we make meaning from the language in the landscape. We read our world.

12

In this way, Boykoff and Sand make a strong argument for the “inadvertent” audience; even though, as I mention earlier, public space can be a zone where isolatos pass through — the old “lonely crowd” of hoary sociological studies — it can also be a site where reading happens. Clearly, as the Sidewalk Blogger’s experience shows, signs that called out “IM/PEACH” do not seem to last long in the landscape; they have been read, understood, and determined to be unfit for public consumption by a citizen (or public official). Still, the inadvertent audience also may in fact be the observant and like-minded reader/passerby who would receive these language interventions as mirrors of their unspoken or unheard thoughts. Which is to say: guerrilla poetry may succumb, in part, to the dangers of “circular address”; in other words, one might argue that their language interventions are principally for those “already-converted.”

13

Even so, though we need a political poetry of conversion — that is to say, a poetry which invites and hails those people who may not yet “know” the narratives that might induce their resistance to a war or a political policy or an administration — we also need a poetry of provocation, of controversy, of confrontation. In the context of the post-9/11 Bush years, when the language of dissent itself had been disappeared, these guerrilla poets provided what amounted to a kind of public service, disseminating their own poetic versions of Public Service Announcements.

To wit, Boykoff and Sand muse:

14

One might consider whether the slogan is, by definition, reductive language. Rooted in the Gaelic word that translates as “to shout,” the slogan is an utterance that is useful and immediate. PIPA’s statement on the slogan attempts a recuperation, demanding that the slogan be language that can “unify people” but also “signal the difficulty in doing so.”

15

Since each of these four projects examined in the book employed poetry and poetic relationships to language, much work remains in elucidating and developing how such poets intervene on and propose other directions in what are by now rote practices of political activism: postering, flyering, and sign-making. Boykoff and Sand embrace the notion of the poet as “culture worker” rather than propagandist, which is a critical step toward articulating how poets might not only change the way in which activism is done, but also change the notion of what sort of world the social activist proffers by her very word/deeds.

16

A sanguine optimism courses through the veins of Landscapes of Dissent; the jaundiced poet or activist might note that the actual work of these projects was ephemeral, and limited in scope and audience, compared not only to mass media publication but also to a modestly-trafficked blog or Facebook page. Even the unending narcissism that secures the future of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) does not mitigate the parallel energies that draw poets into the world; at the recent AWP conference in early 2009, numerous panels highlighted and promoting poetry in the schools, poetry in prisons, and poetry in public spaces. In limiting their examination to non-institutional “guerrilla” poetries, Boykoff and Sand have risked leaving out some powerful and widely resonating poetic and literary interventions in our cultural moment — such as Poems from Guantanamo, Operation Homecoming, Poets Against the War, Iraq Veterans Against the War, etc. To be fair, Landscapes of Dissent does not offer itself as an exhaustive examination of dissident poetries, and maybe such an endeavor would be impossible anyway, because of the fundamentally transient and occasional nature of such guerrilla verse.

17

We live at a moment where not only poets, but all of us, risk limiting our rhetorical address to ourselves and those like ourselves. What the guerrilla poets do, by making real the wars abroad, is to suture spaces in the public sphere where once the abyss of abstract political language existed. When the Sidewalk Blogger places the rising numbers of American soldiers dead in Iraq, or when she juxtaposes the names of local cities and Iraqi cities, she participates in the critical act of what Fredric Jameson called “cognitive mapping” — that work of making visible the invisible relations between ourselves and others, at home and abroad. Landscapes of Dissent, and the guerrilla poets it documents and heralds, challenge simultaneously the parochialism of our poetry and our politics, and provide a useful poetic “global positioning system,” by which we might locate ourselves and where we need to go from here.

Philip Metres

Philip Metres is the author of a number of books, including: To See the Earth (poetry, 2008), Come Together: Imagine Peace (anthology of peace poems, 2008), Behind the Lines: War Resistance Poetry on the American Homefront since 1941 (criticism, 2007). His poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Best American Poetry and Inclined to Speak: Contemporary Arab American Poetry, and he teaches at John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio.