| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 30 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Stephen Mooney and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/mooney-brakhage.shtml

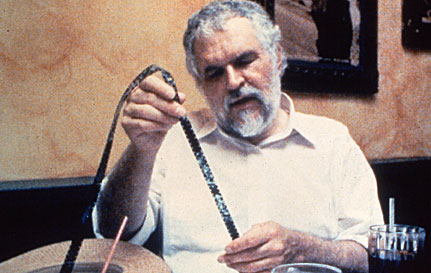

Stan Brakhage: photo courtesy Fred Camper, from Chartres Series: internet site: http://www.fredcamper.com/

1

Stan Brakhage, as one of the foremost avant-garde filmmakers of the 20th Century (indeed right up to his death in 2003), has offered viewers of his films an expanded sense of what the camera can achieve. His influential development of theories of ‘hypnogogic vision’ and ‘moving visual thinking’ complicate the ways in which viewers of his films experience the visual. What is presented on the screen often reflects a discontinuous sense of the camera as eye. What is seen on the screen, and what can be seen, is not presented to us as a cohesive, non-negotiable actuality, but rather as a complex unearthing of cinematic techniques that relate to the physical aspects of seeing, and that engage with the viewer’s own sense of the visual.

2

This paper seeks to show ways in which Stan Brakhage’s ‘just seeing’, and his achievements in cinematic technique in this area, are useful, in an expository way, in the contextualisation of some of the poetic techniques and strategies used in contemporary poetry in relation to the formulation, and manifestation, of complex temporal structures that invoke a sense of ‘Background Temporality’, or sense of temporal engagement that informs the poetry, and the performance of the poetry, at a given time, in a given place, to a given reader or audience.

3

I will demonstrate, in relation to avant-garde and contemporary strategies of representation, such as those adopted in Brakhage’s cinema, how these poetries can engage with forms of discontinuous visuality, visuality that is fractured and multiply activated, particularly in terms of its temporal operation. Specifically I will look at some examples from the poetry of Lee Harwood, Bruce Andrews and Joan Retallack.

4

This is not to suggest that the films of Stan Brakhage, or his cinematic theories, have directly influenced the poets and poetries in question, although Brakhage was certainly in dialogue with certain key modernist poets in the broader tradition of these poetries, such as Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Michael McClure, Louis Zukofsky etc.

5

He states himself (in the ‘Encounter: Brakhage on Brakhage’ interview filmed by Colin Still, which is on the By Brakhage dvd collection — this is from the start of part 2 of the interview) that “[p]robably in my life my richest correspondence has been with poets”.[i]

6

Rather, I would suggest that developments in the avant garde in cinema, such as, and in many cases specifically, those of Brakhage, were influential upon, and engaged with, the poetic traditions these contemporary poetries draw upon, such as the Black Mountain school and Beat Poetry.[ii]

7

In relation to its presentation of visual material Stan Brakhage’s filmmaking explores, amongst other things, the disjunction between the image and cognition; it challenges the processes, and the representational strategies, of visual construction in relation to the filmmaker, and the viewer.

8

As Brakhage himself has put it:

9

My eyes are the poorest aspect of my physiology, and it is quite sensible and understandable that, for those reasons and along those lines, I have developed vision. I mean in order to be able to see at all I had to have such rapid eye shifts and movements that ophthalmologists who were testing me against charts, who were perfectly aware that with the aberrations of my eyes — I shouldn’t be able to see where the chart was on the wall — have also commented that they never saw anybody with such rapid eye movement, and speculated, I think, quite correctly, that I was, like, putting together from fragments rapidly parsed images in the mind. Now in some sense that is what any one does, but because I was doing it so consciously, so completely consciously, it gave me an understanding and a deep involvement with eyes, eye-brain, you know the mind’s eye, not just what the light passes through.

Almost anything that I was given to photograph, that I was emotionally involved in, I could have done so because my growing, constantly growing and finally come to be concentrated focus on my being, of all my making, is to discover the process of sight itself, the mind’s eye not just the shifts and sicards of these little jellied orbs but their limits and possibilities too, and the crossbreed of neurons that make the eyeball so close to the brain you can call it a surfacing of the brain, the whole innards, not just the brain, but as that reaches out to the fingertips along the whole nervous system to create a nervous system feedback of visual music. And I began that without knowing quite what I was doing in ‘Dog Star Man’ when I painted on film.

(Brakhage, ‘Encounter: Brakhage on Brakhage — part 2’, By Brakhage)

10

Brakhage’s filmmaking reiterates rhythm in its movements of shot and image, and its extraordinary, and variously abstract, uses of techniques such as montage, plastic cutting, passage, etc. In fact his location of internal biological rhythms, such as the 24 hour light based circadian cycle, or a temperature cycle that is warmest in the afternoon and coolest at night[iii] at the heart of his ‘handheld’ composition process is often accomplished through the complicated visuality of the film as related to a ‘bodily sense’ of the camera. This bodily sense is related to the impression created of the camera as an extension of, or part of, interestingly, both the filmmaker and of the viewer. Blinking, shaking, shuddering, revolving, multiply focused.

11

This speaks somewhat, for example, of the collision of natural biological and social timescales, of the rhythms of our bodies and those of our society that Henri Lefebvre speaks of in the final part of his Critique of Everyday Life (published in English as Rhythmanalysis)[iv]. The bodies of both the filmmaker and the viewer are seen as compositional, and receptive.

12

This paper will not attempt to present a detailed scientific examination of the biology of vision and sight, or indeed engage in a scientific discourse related to that. Instead, we are concerned here with the relation of visual effects in Brakhage’s cinema that can be described as related to a ‘bodily’ conception of visuality to a broader literary sense as used by Michael McClure where he said that:

13

The mind is inseparable from the body and too much energy has been spent looking at the mind (whether shapely or not) of poetry, and not enough at the body. Similarly, the structure of poetry had often been looked at (though not clearly), but such structure had never been looked at as an extension of physiology.[v]

14

The frame here is poetics, and the poetics of the body. McClure’s employment of ‘beast language’ and his ‘bio-alchemical’ transfer of energy between poet and poem attempt to link the generation of poetic language, and its reception by the reader, with the physiological presence of the poet and the reader.[vi] That Brakhage was interested in this notion, seems clear. In specific relation to this in his own work Brakhage noted in a letter to the poet Robert Duncan that he sought to:

15

become attuned to my own nerve’s impulse in the immediate sensory receiving of images,[vii]

16

and in relation to the poetics of Michael McClure that:

17

my display of visions (like Michael’s enverbaled vision) came to the film window (“the page”?) directly from my physical self, the rhythms and tones of my biological response, my very breath and organic breadth of being.[viii]

18

Brakhage is concerned with what Guy Davenport describes as the “eye’s intelligence”, the ability of the eye to ‘see’ what lies before it, and to communicate, or interpret, that seeing. Also, the relation of this to the visual, and temporal, processing of both the viewer and the filmmaker through the camera, and the composition process.[ix] What is being seen? Is this representable in time? Is this sense of the visual presented by the eye, indeed to the eye by the camera, occurring within a linear movement of temporality, or is that movement fractured, and multifaceted, as with the complicated, non-linear montage that Grauer identifies in Brakhage’s work as negative syntax? [x]

19

One aspect of Brakhage’s theoretical framework in relation to this interpreting of the eye’s intelligence is what he called ‘moving visual thinking’. He referred to this as:

20

a form of awareness close to the actual excitement of the nervous system … . awareness before it develops into visual forms of focused attention,[xi]

21

or as:

22

a streaming of shapes that aren’t nameable — a vast visual ‘song’ of the cells expressing their internal life,[xii]

23

and sought to actualise this, and other concepts related to that which precedes, as well as presages, visuality in his filmmaking.

24

Of specific relation to these preceding and presaging aspects of visuality in the expansion of notions of the visual in filmmaking practice that Brakhage has become renowned for, is his focus on hypnogogic vision, which he describes as:

25

what you see through your eyes closed — at first a field of grainy, shifting, multi-coloured sands that gradually assume various shapes. Its optic feedback: the nervous system projects what you have previously experienced — your visual memories — into the optic nerve endings.[xiii]

26

The Oxford English Dictionary records the term hypnogogic (also spelled hypnagogic) as an “adjective relating to the state immediately before falling asleep” from the Greek hupnos ‘sleep’ and agogos ‘leading’.[xiv]

27

What Brakhage describes as optic feedback here, and, with ‘moving visual thinking’, awareness before it develops into visual forms of focused attention, are very significant for the examination of poetries that seek to complicate the temporal relationship of the reader to the text, and that use visual and compositional means related to visuality to do so. We shall come back to this in more detail. Suffice to say for now that these conceptual frameworks Brakhage makes use of can be brought to bear usefully upon complex manifestations of temporal operation in textualities that invoke visuality.

28

Brakhage’s work within the visual field spans decades of exploration and experimentation. Of the many and varied techniques Brakhage has employed to convey a sense of the bodily, and to complicate vision, can be listed the following: the obscuring of parts of the image, or the frame; very rapid cuts between frames, and shots; physical jerks, and movements of the camera, or the film; tears and scratches, or indeed, painting and writing directly onto the surface of the celluloid; extreme close-ups, blurrings, and mistings of the image; superimpositions of images on top of sometimes multiple other images; submersion of images within the frame; flarings, and explosions, of light and dark; marked alterations in the visual rhythm and speed; reversals of motion; inversions of both image and frame; plastic cutting of images,[xv] and so on …

29

While many of these specific techniques are not directly analogous to textual practices in the experimental, and linguistically innovative poetries,[xvi] of the late 20th century, and early 21st century, the spirit of their representational complexity and experimentation, that which characterised much of the developments in the Avant-Garde across the arts in that period, certainly is.

30

That Brakhage’s work was in constant dialogue with developments in the Avant-Garde is clear, as Millar points out.[xvii] It also seems certain that Brakhage perceived a relation in his work to philosophical, and contemporary, theories of the visual as well. His writings on cinema and poetry, and letters to other filmmakers, poets, and artists illustrate (in a punctuative way) his development, in his work, of a cinematic visuality related to the body, and of ‘just seeing’ alongside this;

31

For years I’ve baked film, used high-speed film and sprayed Clorox on it so as to bring out grain clusters. You might say it’s inspired by impressionism, but it is a great deal more contemporary than that. I have been trying for years to bring out that quality of sight, of closed-eye vision. I see pictures in memory by the dots and moving patterns of closed-eye vision — those explosions you can see by rubbing; there’s a whole world of moving pattern.[xviii]

32

Edward S. Small says, in relation to Brakhage, psychology, and vision that:

33

For contemporary cognitive and perceptual psychology, many of Brakhage’s “closed-eye vision” images are currently named and categorized. These would include afterimages, meditation imagery, hallucinations, dreams, memory, eidetic images, thought images, hypnopompic/hypnogogic imagery, and entoptic images (i.e., closed-eye percepts of “floaters,” actual optic debris, not a true mental image) [… ] Actually, I was surprised to learn that Brakhage seems not unaware of the technical terms, of the “scientific” categories of mental images.[xix]

34

While Brakhage uses the term ‘visual’ he does not, I think, imply a ‘completed’ form of visuality, one that is scientifically, or psychologically exhausted, but rather an indefinite expansive form that includes aspects of the visual that make image incomplete. It is this sense of the visual that we are concerned with here, in relation to the action of the visual in poetry.

35

In Anticipation of The Night (1958), one of Brakhage’s first major works we see great play with light and dark, and with movement between images, and scenes. An intense, one might say claustrophobic, sense of presence is created as a shadow figure moves across the screen intercut with rapid representations of movement, as of lights filmed from a moving vehicle, or of light and shadow interplayed on the camera lense. Road movement scenes of foliage, and the sky, in light and dark, with rapid, and often disorientating, shifts in directional motion add to the sense of discontinuous relationships the eyes’ action of viewing raises. A visually, and temporally, variant relation of image to movement in intercut fairground scenes are particularly effective in their complex rhythmic use of light, shade, and motion, alternatively increasing and reducing in velocity, direction, intensity, and focus.

36

This play with light and dark, and with movement between images, and scenes, is related to proportional relationships between visual elements, and to directionality as the eye is continually led off the edge of the visual frame in opposing, and confusing, directions, while other images, and frames, are indistinct, or out of focus.

37

As Fred Camper has put it:

38

To view a Brakhage film is to constantly experience deflections of one’s gaze.[xx]

39

Brakhage has sought to achieve visual effects in his films that relate to the gaze, and to the presaging of that sense of the gaze. He describes his film The Dante Quartet (1987), as “a movie that reflects the nervous system’s basic sense of being”.[xxi]

40

Looking specifically at each of the 1st and 3rd sections of the film, for example, ‘Hell Itself’ and ‘Purgation’ respectively, we can see clear evidence of this assertion. Swirls and shocks of textured colour emblazon the screen in the former, with spectacular shifts in velocity as the visual frame accelerates, and decelerates, markedly, and freezes momentarily, in a breathtaking display of motion and action.

41

P Adams Sitney says specifically of ‘Hell Itself’ that:

42

[… ] the optical printing, holding some frames as long as half a second, retards its thick churning motion, then spasmodically accelerates and decelerates it, in three unequally long phrases.[xxii]

43

This description can be seen as related to the surges in electrical impulse, or signal, the brain receives from the eyes’ motion, spatial, and colour sensors, where the excitement of the nervous system, in terms of cerebral response to visual stimuli, in response to the film’s visual display, is itself invoked by the film. Such an explosive energy, and sense of unrestrained movement where sections of the visual image appear to mutate, and move independently from one another, is expanded in the darker ‘Purgation’ section of the film where the complex motion is fractured, caught and released at speed, and superimposed upon another series of film images. Here hypnogogic (closed eye) visuality is strongly accessed through its graininess, and sense of optic feedback, with its resolution into, and out of, view of image within the feedback, with the halting, and fading, of light and colour.

44

Brakhage’s view of vision in relation to image as ‘just seeing’, including open-eye, peripheral, and hypnogogic vision, along with ‘moving visual thinking’, and other areas related to the nervous system’s processing of vision (i.e.: the eyes’ transmittance of visual stimulus information through electrical impulse, and the brain’s processing of this), is here related to the complex interplay of visual and other elements, where there is an emphasis on exposing the visual, as what is ‘seen’, itself to view. This includes, I would suggest, conceptualisations of visual components, or actions, such as those above, which can be described as not so much pre-sensual (existing before sense), as proto-sensual, or presaging sensuality, themselves constituting a part of a broader coming into action of that sense.

45

Here ‘proto-’ is conceived as composed of, or composing, the sensual in its transitional state towards an inherently incomplete dynamic form of the visual. It suggests a desired state of the visual that is not a coherent, completed, and therefore motionless, relation of the eye’s intelligence to the film it engages with. It suggests, rather, an expanded sense of visuality that seeks to acknowledge a dynamic incompleteness of visual representation, and the significance of the eye and its intelligence to that; that this incompleteness is itself a necessity of its functioning as visuality, an application that I will also apply to the poetry I examine in this paper.

46

Brakhage’s work is of itself significant to the formulation of a Background Temporality that engages with inherently incomplete forms of representation. This sense of ‘just seeing’ that invokes bodily aspects of composition, and response, that Brakhage not only speaks about, but also expounds, in his cinematic practice, suggests a phenomenological engagement with the operation of temporal structures in the reception of image, and of text. I see this link as especially relevant given the significance of Bergson’s ideas on temporality, and Deleuze’s work on the time image and the movement image in relation to time and the visual in cinema.

47

In his 1977 essay, ‘Poetry and Film’, Brakhage has stated that:

48

[… ] film and poetry relate closely for this reason: poetry is dependent upon a language that is in the air. All poets inherit at scratch a language — I mean they inherit it the first time they start scratching their ears with sound and start to make sense out of it, that is, as babies. And they inherit not only their language, but the possibility of language [… ] poets are forever surrounded by other people using this language and using it all the time in a great variety of ways, which shapes each poet’s sense of that language.[xxiii]

49

It seems to me that Brakhage here refers to that sense of a ‘non-degree zero’ that John Cage famously identified with his 4’33” composition. Cage conceived the piece to be performed in total silence on the part of the instrumentalist(s), in three segments, the transition from one to another of which would be signalled by an action on the part of the instrumentalist(s), such as the lowering, and then raising of the instrument, or part of the instrument, such as the lid of the keyboard on a piano. He quickly came to realise that background noises intervened on every occasion. Even within a sound-proof environment, silence for the hearer was impossible to achieve. The bodily sounds of respiration, the beat of the heart, and the tiny sound of blood rushing through the blood vessels of the ear itself made this inevitably so. Sounds, he noted, were sensed through the body’s bones and skin, as vibration, as well as processed by the ear as aural signals.

50

As Cage’s 4’33” demonstrated, the non-degree zero of silence, silence as a total absence of sound does not, and cannot, exist, on the most fundamental biological level of the hearer, likewise one can suppose that what Brakhage calls the possibility of language here is also never fundamentally absent. The work on semiotics, and literary theory, of Ferdinand de Saussure, Roland Barthes, Jacque Derrida, and Jean Baudrillard, for example, would suggest that language is in varying ways fundamentally present in human interaction with environment, and with idea.

51

The significance of this is exemplified by Michael Nyman, in his seminal Experimental Music, on Cage’s experimentation with silence, where he says:

52

4’33” is a demonstration of the non-existence of silence, of the permanent presence of sounds around us, of the fact that they are worthy of attention, and that for Cage ‘environmental sounds and noises are more useful aesthetically than the sounds produced by the world’s musical cultures’. 4’33” is not a negation of music but an affirmation of its omnipresence.[xxiv]

53

It is this sense of Brakhage’s ‘language’ and ‘possibility of language’, connected to Cage’s non-existence of silence, that I would maintain relates to the concept of a Background Temporality that I will examine as pertinent to contemporary poetry and poetics, particularly in performance. This sense is conceived as operating not just on the poet at the time of composition, informing his or her sense of timing and rhythm, structure and visuality, but also upon the reader, and/or listener, at the time of reading, or hearing the poem. This temporal sense ‘in the air’, can be viewed as related to social, and cultural, understandings of what is (contemporary) temporality, as well as the physical interruptions, and reciprocal action, and response, the immediate environment imposes upon the poet/reader/listener. The variability, and reciprocity, in this sense is key. As Lawrence Upton has written:

54

Performance of the same text may vary quite widely from day to day and performer to performer. To some this might be seen as a weakness or failure, but I welcome it. Let us give poetry, from those who wish to, physicality and the frailties and/or variety of physicality.[xxv]

55

cris cheek says of the presence of performativity in writing that:

56

All writing involves ‘performance’, takes part in the performance of language. We know now, that any mark (the spilt puddle of beer on a public bar or the found smudged text, the graffitti on a wall, woodbark rubbings — within traditions of poetry, shamanic interpolation and graphic notation) is performable, can be read as ‘sign’ — by human body, by voice, by breath.[xxvi]

57

This external sense of temporality (related, in some degree to what Henri Lefebvre’s refers to as ‘social rhythms’[xxvii]), from the setting, the environment, the social dynamic of the room, can be said to combine with, or cohabit with, the individual sense of interior temporality that the poet/reader/listener employs, or has employed, in his, or her, experience of the poem. (Here interior temporality being that generated by, or present within, the individual physiology and psychology of each person in their relation to the world at that particular place, at that particular time — related to Lefebvre’s ‘internal rhythms’).

58

It is this action of combination and interaction between the internal and external perceptions, and of temporality, that I would identify as Background Temporality for our purposes here (rather than the simple togetherness of the two).

59

As Cage’s 4’33”,

60

in positing the absence of sound points to any and all sounds as a material for music [,][xxviii]

61

so I would suggest the ever-present, and pervasive, nature of external, and internal temporal influences upon the performer, and the reader/listener/experiencer similarly admits these elements, and their interaction as components, to the temporality of the performativity, and the textuality encountered (visual, aural, or kinetic in its focus, or some combination of these).

62

Brakhage’s experimentation with the bodily sense of the camera, and the visual, and with the visual practices of the viewer, show an awareness of the consequence of what I am referring to here as Background Temporality to the generation, and reception, of visuality in this sense, and an interaction with it.

¶

63

Within the specific poetics I wish to explore, similar conceptions of the bodily, bodily presence in the visual field of the poem, and an inherent incompleteness related to background temporal functioning, are discernable, and, therefore, usefully examined alongside the cinematic techniques Brakhage uses in relation to these conceptions. The significance of the reader (or audient) to both the poetic object, and to the background temporality acting upon it, can be seen in the work of Lee Harwood, a poet often associated with The British Poetry Revival,[xxix] and one whose fracturing, and framing, operations upon perspective are particularly instructive. Amongst other temporal strategies available in his poetry, there is an employment of, and engagement with, cinematic, and inherently incomplete visuality, in its conception of temporal frame, and its bodily relation of the presence of the reader in the structure of the poem, and in its performance, is especially significant here.

64

Reader response theories place different emphases on the status of the reader in relation to the poem, from the individual reader experience emphasised by C S Lewis and Stanley Fish, to the more ‘uniformist’ emphasis of Wolfgang Iser and Hans-Robert Jauss, where the relationship is more text driven, or driven within the parameters of the text. Fish, for example, stresses that interpretive communities share reading conventions for understanding texts in certain ways. These communities activate the text, making literature an activity of both production and consumption.[xxx] For Iser, a text can be viewed as an effect of reading rather than an object in itself. His ‘implied reader’ returns reader-response criticism to the study of the text through defining readers in terms of the text. He locates this implied reader of a poem ‘in’ the poem, in the sense that the poem requires this reader.[xxxi] The poem regulates perception, and the reader is active only within limits set by the poem. In both cases, this location of the reader in relation to the text is crucial.

65

Harwood’s poetics suggests a further move. In his 1972 conversation with Eric Mottram, has said of the poetic object:

66

[… ] a poem is therefore a common, shared object. And the object for me essentially must have loose ends, it must be unfinished, because the reader or anybody else outside you has to complete it and make the final thing, if ever there is to be a final thing.[xxxii]

67

In this sense his use of visual, and temporal, frame brakes is significant, and implies more than a collaboration by the reader with the text to generate conceptual meaning, but also the joint-construction of the visuality, and temporality, of the poem.

68

Harwood’s reader is in some ways invoked by the text; the poem is unfinished until the reader engages with it, picks it up, and handles it; the poem anticipates its reader. Yet, the joint act of production and consumption that the reader engages in with the poem is complicated by the very presence of the reader him-, or herself. This reader is active both inside and outside of the poem. The aspect of the reader that can be said to activate the poem is not a single thing. This aspect, as with perspective, is presented as facetted. Within the reader’s role in the formulation of the text is an acknowledgement that the idea of a completed, final thing is itself flawed. Instead, we have the implication of a multiply conceived engagement between the text and the reader that will activate it, and operate within its parameters.

69

I would suggest that this fascetting of perspective, of both the reader and the poem, is related to the conception of the bodily in Michael McClure’s poetry, and to Stan Brakhage’s conception of a bodily sense of the visual. The reader’s physical, and perspective, presence continually orientates, and re-orientates, Harwood’s poems spatially and temporally. As Aodhán McCardle puts it in relation to the reader and the visual in Harwood’s poetry:

70

What is crucial to Lee Harwood’s work is the way the visual is allowed to dominate. The faculties used to decipher or interact with the poems are those used mainly for visual material. Semantic or grammatical map reading occurs in Harwood’s poetry but only as far as the surface, after which the faculties used to experience or explore the visual kick in; what cannot be encapsulated in writing but may be triggered by writing or reading.[xxxiii]

71

Harwood often uses dashes and spacings to indicate shifts in frame or picture ‘windows’ into distinct ‘areas’ of the poem — these are often represented in visual or temporal ways. The concept of frame seems more appropriate here than ideas of level or layer, as these suggest a hierarchical structure somewhat at odds with the sense of situated-ness or ‘within-ness’ (or even a co-existence of ‘within-nesses’) that occur throughout Harwood’s poetry.

72

For example, in ‘Gilded White’ these framic separations often signify temporally distinct moments, and/or isolated complexities of the visual — the effect of these constructions of the visual (and distinct moments) impinging upon one-another gives rise to a composite complex operation of often unformed temporalities and visualities (‘composite complex’ is used as a term here to mean the complicated interaction of parts within a notional ‘whole’, where ‘composite’, as a term, is insufficient to describe the operation, as it suggests a finishedness or completeness — ‘composite complex’ suggests an engagement, not with a composite, or with multiple composites, but rather, with a changing dynamic of parts within multiple composite manifestations of a whole, or wholes.)

73

From ‘Gilded White’ then:

74

I look down on this from a high window

beside the window stands a tall grey feather

trimmed with charms your gift

hung with small bells and beads and a moon

softly wrapped in wool[xxxiv]

75

Here there is a visual break triggered by the space between ‘charms’ and ‘your gift’ even though there is clearly a conceptual link between the two ‘sections’ emphasised by the break — sight and the visual are being invoked, though importantly not finalised, or completed, in its function.

76

the day may turn a soft dull light

to a brightness a yellow glitter in the snow

a white cloud in a corner of the window

the ghost of a half moon in the sky

77

Very clearly, the play of light as it filters through multiple frames of the visual is accessed here, with its implication of temporal, and spatial, reorganisation — the visual is again incomplete, shifting its representation across the cornea — it is more concerned with the reception of light than the concreteness of the resultant image.

78

on a snow covered path

or a street in a city miles away

a stillness. a middle aged woman pauses by the arch

and knocks snow from her shoes

an old man stands erect by the Via Orfeo

his cheap shirt washed ironed and neatly buttoned

Japan is a long way away Italy is a long way away

California is a long way away Sussex is a long way away

but all gently wrapped together in this moment

your gift

79

The acceleration of withinnesses towards the end of the poem here, of visual, and temporal, frames containing, and intersecting, each other creates a sensation of the visual overwhelming the eye, of the visual as a complex composite of cues and non cues, of light, and of motion, that resist the completeness of image. This suggests a representation of the visual, and of temporality, that is connected to modernist concerns with representation, such as the fragment, and facet, explored in cubism, or the disjunction invoked in surrealism. Harwood’s framic structure suggests also to me an engagement with the developments in avant-gardist cinematic technique such as those employed by Brakhage in montage, plastic cutting, vibration, blurring etc.

80

Harwood’s presentation here, and elsewhere in his poetry, is concerned with the disjunction of visuality — it is a representation of the visual as temporalised, and temporalised in a disjunctive way. We see not only shifting between temporal frames, and reference, but also the use of visual elements as temporal objects that are not themselves either contiguous to, or dependant on, each other. Frames possess an unfixed quality, durationally and rhythmically.

81

The challenge to the visual processes of construction, of frame, image, and language, in relation to the poet and the text, and the text and the reader, are complicated further by Harwood in his readings of his poems.

82

In a published recording of ‘October Night’, for example, he reads:

83

Eyes Shut

“you were in another day”

off in the distant mountains

where the darkness breathes

and the dark silhouette of a hillside

edges a charcoal grey sky.

A seeming solidity, though thin as paper.

A near astonishment at the “facts”,

the surrounding sounds and sights.

The “what is this?”, “who is… ?”.

No step back possible

But a step towards? out?

Behind your grey eyes.. These surfaces[xxxv]

84

as

85

Eyes Shut /

“you were in another day” /

off in the distant mountains /

where the darkness / breathes /

and the black silhouette of a hillside /

edges a / charcoal grey sky. /

A seeming / solidity, / though / thin as paper. /

A near / astonishment / at the “facts”, /

the surrounding / sounds and / sights. /

The / “what is this?”, / “who is… ?”. /

No step back possible. /

But a step towards? / out? /

Behind / your grey eyes.. / These surfaces /[xxxvi]

86

The complexity of the poem’s surfaces, and visuality, become more apparent with the addition of the poet’s physical voice. The use of contained temporal instances, and visual blocks, marked within quotation marks is an interesting set of instances here. Their use implies a structural break in the poem, and in the ‘line’ as used in the poem (where used in that way), and a consequent movement into, or out of, frame by the poem, and/or reader (reader as writer, listener, etc here) – a movement between frames. Harwood’s reading of

87

The / “what is this?”, / “who is… ?”. /

88

would seem to correspond strikingly with the placings of these frame breaks, and accesses a linguistically understood sense of emphasis, and location, attached to the use of quotation marks, and other textual markers.

89

What is even more interesting in his reading practice is the complication involved in his reading of clusterings of words such as:

90

A near / astonishment / at the “facts”, /

the surrounding / sounds and / sights. / [,]

91

where the contained temporal, and visual, markers of the text, such as quotation marks in this case, are de-emphasised by his ‘riding through’, or lack of acknowledgement of, that syntactical marker. Held in relation to the poem on the page this serves to, consequently, re-emphasise the break in the poem’s structure (temporally, and spatially). His insertion, in the reading, of rhythmic markers where none syntactically or visually appear visually on the page, or the riding over of visual markers, such as extra spacing or gaps between words, and lines, is another form of complication of visuality in the poem; one that links this visuality to the dynamic of the poem as ‘unfinished’ in its realisation. With visuality thus temporalised, Background Temporality becomes constitutive in both the visual, and vision, in relation to the poem.

92

The challenge to visual authority that the placing of the wordscape ‘facts’ within de-acknowledged quotation marks, in close proximity to spatially unacknowledged temporal markers, for example, signifies to me a complicated transfer of quotational authority to those wordscapes so marked out: “astonishment”, “sounds”, “sights”. It represents, in this light, a consequent challenge to the visual, and temporal, ‘marker’, and textual emphasis as it applies to poetry. This particularly so when encountered in proximity to his oral readings of that poetry.

93

The emphasis here, and elsewhere in Harwood’s poetry, is not upon the making of surface at the level of the sentence, or the word, or, consequently, upon the equal value of all words that Lyn Hejinian notes, through William James, in the writing of Gertrude Stein:

94

[James] posits the sentence also as a planar surface where the vanishing point is on every word, and as a landscape, which is to be perceived or thought as a whole.[xxxvii]

95

Harwood, rather, posits structure as occurring, not at every level, but in relation, instead, to the frame, with visual and syntactical relationships, and breakages, envisaged as operating to some degree outside of transcending hierarchical patterning. This constitutes a complication, and expansion, of the visual, and the visuality of the poem’s surface; here a complicated frame of emphasis that incorporates three temporal breaks.

96

This framic emphasis is significant in its effect upon language, and its reception, in Harwood’s poetry — language, and its use, as invoking the visual is itself visualised, in that it is subjected to disjunctive visual technique. Visual references, and images, are disjunctively temporalised, using disorienting visual strategies that can be called ‘cinematic’, especially when examined in relation to Brakhage’s use of avant-gardist cinematic technique. This sense of poetry as cinematic differs from that of James Joyce, or Ezra Pound (or other modernist writers), where the emphasis is perhaps more on a kineticised fragmentation, precisely in its temporalising of language in this way.[xxxviii]

97

This is not to suggest that Harwood’s frames are always discontinuous, or that this is the only temporal actioning in Harwood’s poetry … or indeed that this form of temporal complication and actioning dominates his poetry. As with all of the poets examined here, he uses many formulations of temporality in his work. In Harwood, poems and blocks within poems often generate forms of narrative time, which are not strongly discontinuous in the sense outlined above. His use of discontinuity, and of incompleteness and unfinishedness, of inherently incomplete states of temporality, is often subtly, or indeed very subtly, employed, producing quietly discontinuous effects in poems that on their surface seem deceptively straightforward or coherent.

98

The various forms of disjunctive temporalisation of the visual that Harwood utilises can be seen as relating to the inherently incomplete states that are so significant for the Background Temporality proposed here.

¶

99

Inherently incomplete states, in many ways, come into their own in the poetry of Bruce Andrews. These operate more visibly and actively than in Harwood’s poetry, for example. In the locating of a sense of a Background Temporality in contemporary poetics, Andrews’ work is exceptionally useful. It also bears a relation to the idea of the ‘proto-sensual’, and to the bodily, that Brakhage’s ‘just seeing’ can help illuminate.

100

Andrews is one of the major poets, and a founding member of, the influential Language Poetry school in the US. The concern in his work with the uses, and boundaries, of language in poetry and poetic form, and in public language, significantly complicate the sensual relationship of the reader/listener/viewer, and of the writer/performer, to the text, and the performance of the text.[xxxix]

101

In a radio interview with Charles Bernstein on the LINEbreak programme in 1996, Andrews recounted his method of composition:

102

… to generate large amounts of material on very small pieces of paper — one, two, three, four, five words at a time, in clusters, short fragments of phrases, or pre-phrases, and then compose the work, sometimes much later… then when I had written the raw materials, into works based on a whole series of other decisions that I’ll make later, so it’s more like editing film footage. So that the editing process becomes the composing process. Or that’s what gets focused on, more than some kind of point-of-inspiration moment that I actually wrote the words on.[xl]

103

As with Brakhage’s sense of nerve impulse as ‘awareness before it develops into visual forms of focused attention’ Andrews’ composition process in some ways adopts a presaging of the poetic phrase (his main ‘unit of composition’). Not only is this a complication of the perceived process of construction, and composition, of the poem in its relation to the reader, the technique also imbues the language of the poem with a sub-compositional dynamic got to do with the transmission of the language itself from a ‘proto-’ to an ‘inherently incomplete’ poetic form.

104

From the ‘Sell Your Friends’ section of I don’t Have Any Paper So Shut Up:

105

Sell your friends: think rich; stupider

is a chemical process, the language of your body is a language

of molecules — sin saves what Jesus spends. Where can I buy a

good used cigar? Infrastructure hamstrung by sinkhole root

raze rasta go go go pink sweater on brain scan; your mongrel

prefers my mongrel, crackle against it. Cellular white fang

is reverence tampers with tip solidarity

crispy fried adults, hair evident — homework bent my clasp.[xli]

106

or from Give Em Enough Rope:

107

voice

pomp atom

implicative cottony brake

angel volte face

charity sinuous be movement walkie-talkie

if u c rd th

quick whom fete repute![xlii]

108

In their patternings, and interrelations, these phrases, and ‘pre-phrases’, as Andrews calls them (those language units that presage ‘phrase’), from the examples above, retain a sense of their proto-formation as language units in the composition process. This proto-formation is not envisaged as being somehow ‘pre-language’, but rather constituent in the formulation of compositional language that generates Andrews’ published text. This as analogous to Brakhage’s ‘just seeing’ retaining the proto-sensual in sense. Likewise, it can be said that Andrews’ proto-formation of language is retained (not just ‘contained’, as this implies a restrictive relationship, rather than a more open interactive one) in the published text of his poem. The point at which the word-unit, or the phrase-unit, enters the poem is, in this sense, not a singular ‘point’ at all, but, rather, manifests as a multiplicity of interventions, that carry with them differing, and varying, filtrations of Background Temporality into the poem.

109

The sense of Background Temporality that informs the poem is complicated not just by these interventions of compositional Background Temporality, but also by the presaging of an inherently incomplete dynamic as poetic form that the composition process is engaged with.

110

This raises the question of the relationship of Background Temporality to experience. Does Background Temporality, then, posit the notion of temporality floating around, in some sense, external to the experiencer, waiting to be accessed in experience? This would formulate it as a type of objective time, external to, and existing independently from, the subject, which is engaged by consciousness. This is not what I am proposing with Background Temporality here. Instead, I would envisage Background Temporality as related to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s conception of phenomenological time related to the body in Phenomenology of Perception (PofP): “It arises from my relation to things” (author’s emphasis).[xliii]

111

There is an implication with Background Temporality of an acting upon (or as part of) experience, and the experience of temporality. While this does not presuppose a necessarily pre-experience existence of external or internal temporality waiting to be engaged by experience, it does suggest that experience activates some sort of interaction with these internal and external components that I have identified. How then to account for a sense of ‘in the air’ temporality, as both separate, or interlinked, external and internal influences that combine in the composition of temporality?

112

I would suggest that the ‘somethings’ pre-existing which become (or are brought about as) the internal and external components of Background Temporality at the point of activation (the conceptual ‘proto-’ that I’ve been referring to) are not identifiable, or accessible, as temporality until a temporal focus is placed upon them. The activation process (experience) frames, or brings about a framing of, a temporal field (or simultaneity), that is part of experience itself; “consciousness deploys or constitutes time” (PofP, p. 414) to quote Merleau-Ponty, or more precisely, as he puts it, that consciousness “is the very action of temporalisation” (PofP, pp. 424-425).

113

His assertion that:

114

In every focusing movement my body unites present, past and future, it secretes time, or rather it becomes that location in nature where, for the first time events, instead of pushing each other into the realm of being, project round the present a double horizon of past and future and acquire a historical orientation. [… ] My body takes possession of time; it brings into existence a past and a future for a present; it is not a thing, but creates time instead of submitting to it [,] (PofP, p. 240)

(my emphasis)

115

supports the idea that Background Temporality does not exist, in this sense, until experienced (in terms of the phenomenological). It is the something ‘in the [internal or external] air’ that cannot be accessed (temporally), until experience is temporalised … and continuously retemporalised:

116

But every act of focusing must be renewed, otherwise it falls into unconsciousness. The object remains clearly before me provided that I run my eyes over it, free-ranging scope being an essential property of the gaze. The hold which it gives us upon a segment of time, the synthesis which it effects are themselves temporal phenomena which pass, and can be recaptured only in a fresh act which is itself temporal. The claim to objectivity laid by each perceptual act is remade by its successor, again disappointed and once again made. (PofP, p. 240)

117

Background Temporality, then, is best conceptualised as occurring at, and coming about as part of, the field of experience. This does not require Background Temporality to be prior to experience (in that sense of ‘proto-’), but suggests that it is in some sense simultaneous with, or ‘post-’, experience, and is therefore fundamental to present temporality in a compositionary sense that is related to transition in an inherently incomplete dynamic (‘proto-’ in the sense of formationary).

118

In terms of the ‘bodily’, and Background Temporality, Andrews’ performance works, particularly those choreographed for movement, (such as the Ex Why Zee texts) engage with the sense of Background Temporality applicable to individuals in play at the time of the performance, as well as that evoked by the composition process, and the explicit exposition of the poem’s action as an inherently incomplete poetic form. Instructions in the poems such as

119

Arms react, but do not aid.

120

or

121

(Flash frame at point of max

charge — make the point: focus: by tightening up all the writing / lan-

guage around it.) (Spatialize it — stoptime — a more diagrammatic

insistence.)[xliv]

122

from ‘Movement/Writing//Writing/Movement’ are not just instructions to the performer, or the reader. They seem also related to a pre-figuring of movement and text in the form of kinetic impulse not dissimilar to Brakhage’s notion of moving visual thinking.

123

Andrews’ bodily sense of compositional presage in language also bears a significance for the proposition of a Background Temporality; it suggests a very complex temporal model of interventions into the reading-scape of the poem; a model that is connected to an awareness of sensation (of the visual, the aural, the kinetic) that includes the proto-sensual. Viewed alongside Brakhage’s sense of an ‘awareness before it develops into a focused form of attention’, and in relation to that, Michael McClure’s bodily poetics, which locates language in the physicality of the human body, Andrews’ engagement of the kinetic, and its presaging in performance, and in composition, locates language in direct relation to the sensual as temporalised.

¶

124

One further application of Brakhage’s sense of ‘just seeing’ to the study of contemporary poetry, and Background Temporality, is worth flagging up at this point. This relates to presaging, chance operation, and what I shall call the ‘remnant of the visual’, where this refers to the presentation of partial vision, obscured vision, or vision at the periphery in textuality.

125

The chance operations employed in Joan Retallack’s poetry are a case in point. As with the chance operation driven work of John Cage, and Jackson Mac Low, the existence of a ‘source’ text, or coda of sounds, and of a system, or selection, or generation, process, to some degree also can be said to presage, in a technical sense, the language used. The ‘inherently incomplete dynamic’ form (as distinct from an idea of a completed final text) relates to a reception of the work here that extends beyond that work itself. That this is so is particularly clear in Retallack’s Afterrimages poems, which Redell Olson describes as:

126

[… ] snapshots of ongoing processes rather than as sustained catalogues of each and every change [… ] Retallack’s text is bisected by a line across the middle of the page which marks the before and after of this event. The material above the line is repeated below after it has been subjected to a chance operation; Retallack threw paperclips across the upper part of the text and whatever was caught in the spaces of the clips was reproduced below. Like Darboven’s Procedures it is a piece of work which foregrounds itself as a process.[xlv]

127

Process is indeed foregrounded, and in this action the relationship between the ‘source’ text, and the ‘performed’ text, achieved through the application of the specific chance operation involved (the above-the-line, and below-the-line divisions of the text respectively), is emphasised with each in a different way presaging, and generating, the other:

128

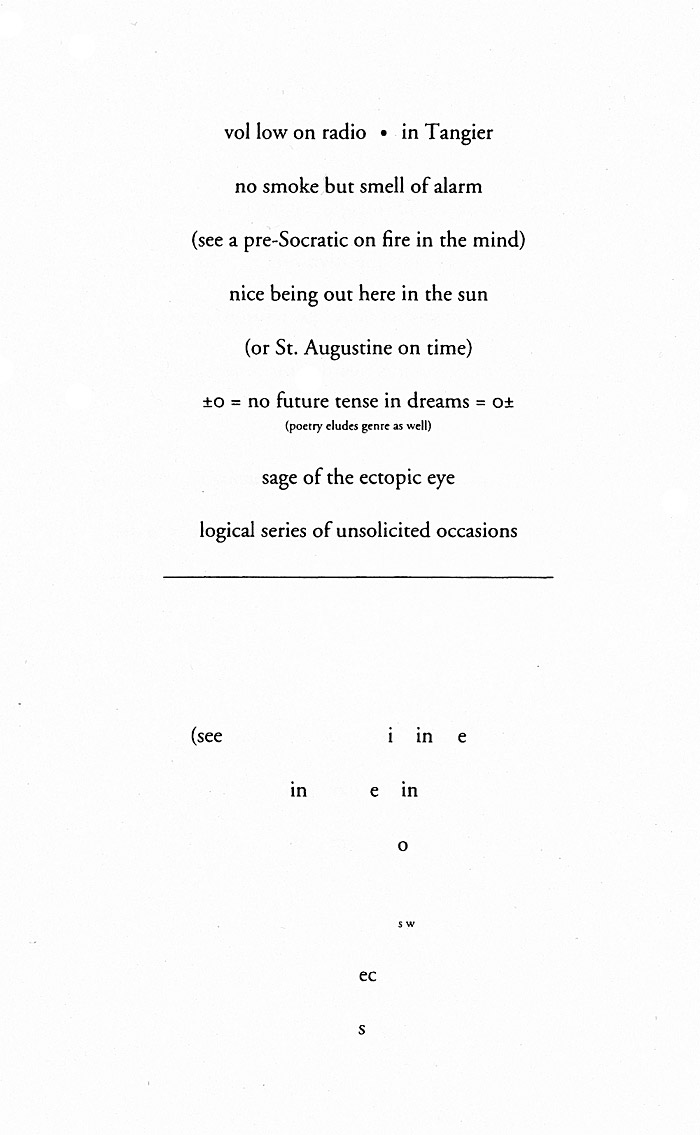

Figure 1 — Joan Retallack, Afterrimages[xlvi]

129

Retallack’s presentation in these poems of what I am calling the ‘remnant of the visual’ as a representation of partial vision, obscured vision, or vision at the periphery, I would suggest, is linked to the visual practices of the Avant-Garde. Brakhage’s pioneering work on the outskirts of the visual in Avant-Garde cinema, of those aspects of the visual that are sublimated, or physiologically complicated, is useful here in examining Retallack’s visual foregrounding.

130

Foregrounding the effect of the process on the visual aspects of the poem is a complication of the poem’s visuality; there is an equation of two visual representations of textuality within the poem, where one is spatially derived from the other; this as a bi-directional exchange related perhaps to a complex fractal relationship of textual parts, where what we see is not the scale-invariance (or ‘self-similar’ relationships of scale) of Chaos Theory,[xlvii] but rather, complex non-linearities of scale that challenge our sense of the visual through a visuality that attempts to encompass both itself and its derivatives, but cannot succeed at doing so within the confines of a coherent visuality.

131

‘Derivative’ here describes the above-the-line, and the below-the-line, as action of the poem’s processes, as well as the poem as derived from the process the poem engages in. This is a term that could well be applied to many of Brakhage’s complications of the visual in his films, where the camera as ‘eye’ is often subverted, and complicated, by techniques that interrupt, and remake its processes. This sense of derivational likewise envisaged as bi-directional, with technique itself derived from aspects of the visual that Brakhage invokes in a relationship with the deriving of a sense of the visual from technique.

132

In terms of poetics, this foregrounding the effect of the process of the poem on its visual aspects amounts to an expansion of the visual that stretches the reader beyond reading practices dependant on the stability and coherence of visuality.

¶

133

In summary, then, I have attempted in this paper to demonstrate some stylistic, and compositional, links between the filmmaking techniques, and practices, of Stan Brakhage, and the textual techniques, and practices, of particular contemporary poets, and poetries, that are connected to those complications, and expansions, of visuality that Brakhage referred to when he spoke of ‘just seeing’.

134

Specifically, the, what I would refer to as, proto-visuality explored in Brakhage’s filmmaking, and the proto-sensuality, and presaging, that some contemporary poetry engages with, in both compositional, and receptive, terms, has been the focus here, along with a corresponding focus on a sense of the bodily. I have attempted to explain the significance of these to the development of a sense of Background Temporality, or a background sense of temporality — Background Temporality as experienced — as this would apply to contemporary poetry as compositional, and as performative. By invoking an extended understanding of sensual mode, rather than a ‘completed’, or ‘complete’, sense of understanding, this Background Temporality is conceptualised, and experienced, this paper would suggest, as a complex composite inherently ‘incomplete’ dynamic of temporal operation in relation to the visual in this case.

[i] Stan Brakhage. ‘Encounter: Brakhage on Brakhage — part 2’. By Brakhage: an anthology. The Criterion Collection. 2003. Disk 1. CC1590D.

[ii] Much has been written on the relation of Stan Brakhage’s work to that of specific poets, and to poetry in a broader sense. See R. Bruce Elder, The Films of Stan Brakhage in the American Tradition of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1998) for a comprehensive situating of Brakhage’s work and writing in relation to an American poetics. See also Brakhage’s own correspondence with the poets Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, and Ronald Johnson, and his own essay ‘Chicago Review Article’, as well as Michael McClure & Steve Anker’s ‘Realm Buster: Stan Brakhage’, all in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002). Further writing by Brakhage on poetry, and its relation to his work, can be found in the essays ‘margin alien’, ‘film: dance’, ‘poetry and film’, and ‘gertrude stein: meditative literature and film’ in essential brakhage (New York: Docuentext/McPherston, 2001). Of interest here also are Tyrus Miller’s ‘Brakhage’s Occasions: Figure, Subjectivity, and Avant-Grade Politics’, and R. Bruce Elder’s ‘Brakhage: Poesis’, both in Stan Brakhage: Filmmaker, ed. by David E James (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), and David James’ ‘The Film-Maker as Romantic Poet: Brakhage and Olson’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Spring, 1982). Also see P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943-2000, 3rd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002) which deals extensively with Brakhage’s work and theory in chapters 6 & 7 (‘The Lyrical Film’ and ‘Major Mythopoeia’), with further comment throughout.

[iii] See Eugene Garfield, ‘Chronobiology: An Internal Clock for All Seasons’ (Parts 1 & 2), Essays of an Information Scientist: Science Literacy, Policy, Evaluation, and other Essays, Vol:11 (1988), 1-13 on the significance of biological rhythms, and the development of Chronobiology, and Michael Treisman ‘The Perception of Time: Philosophical Views and Psychological Evidence’ in The Arguments of Time, ed. by Jeremy Butterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 217-46 for a much more detailed examination of time keeping and multiple internal clocks than is required here.

[iv] Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, trans. by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore (London: Continuum, 2006).

[v] Michael McClure, ‘Scratching the Beat Surface’, in Scratching the Beat Surface (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1982), pp. 1-112 (p. 89).

[vi] See McClure, Scratching the Beat Surface, and his Meat Science Essays, (San Francisco: City Lights, 1963) for more on McClure’s poetics of the body. Also see Rod Phillips “Forest Beatniks” and “Urban Thoreaus”: Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Lew Welch, and Michael McClure (New York: Peter Lang, 2001) for an examination of McClure’s ‘mammalian poetics’.

[vii] Stan Brakhage, ‘Stan Brakhage to Robert Duncan & Jess Collins’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 11-24 (p. 24).

[viii] Stan Brakhage, ‘Chicago Review Article’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48, pp. 38-41 (p. 39).

[ix] See Jerome Hill and Guy Davenport, ‘Stan Brakhage and His Songs’, Ubuweb, Ubuweb:Papers, http://www.ubu.com/papers/hill_davenport-brakhage_songs.html [accessed 10 April 2009] (section II):

Once Brakhage had made Anticipation of the Night (1958) he had discovered that the camera had developed strenuously but one of the modes latent in the simple fact that it was an eye that could share its sight with any other eye. Brakhage’s eye had learned, is still learning, to see in what may prove to be as many modes as physiology and spirit allow — which sounds fatuous until we realize that every eye is pattern-bound in what it sees at all, and beyond that severe limitation is unskilled, stupid of movement, dull, blind in a very real sense. The arts have always taught us to see; for the first time in the history of the world a generation has grown up aware that it can see a figure in dim light as Rembrandt and the autumn trees as Jackson Pollock, or the other way round. The eye’s intelligence must be learned.

[x] See Victor A Grauer, Montage, Realism and the Act of Vision, (1982) http://doktorgee.worldzonepro.com/MontageBook/MontageBook-intro.htm [accessed 10 April 2009] for a very convincing expounding of this aspect of Brakhage’s use of montage. Originally written for the Approaches to Semiotics series, ed. by Thomas Sebeok (1982), but unpublished as part of that series, it is available, in full, online at the address listed above.

[xi] Stan Brakhage, quoted in P Adams Sitney, ‘Tales of the Tribes’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48, pp. 97-132 (p. 111).

[xii] Stan Brakhage, quoted in Suranjan Ganguly, ‘All that is Light: Brakhage at 60’, Sight and Sound, n.s. 3, no. 10 (1993), 20-23 (p. 21).

[xiii] Stan Brakhage, quoted in Ganguly, ‘All that is Light: Brakhage at 60’, p. 21.

[xiv] Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English, 3rd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[xv] Sitney defines Brakhage’s term ‘plastic cutting’ as “the joining of shots at points of movement, close-up or abstraction to soften the brunt of montage”. See Sitney, Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943-2000, p 157. Grauer notes that, in Brakhage’s case, this cutting acts as a form of cubist passage which generates discontinuity and complexity in the montage. See Grauer, Montage, Realism and the Act of Vision, (Chapter 7).

[xvi] ‘Linguistically Innovative Poetry’ is a term generally attributed to the poet, and critic, Gilbert Adair, which seeks to describe a range of distinct, and various, practices in British and Irish alternative poetry that can be said to have its roots in the likewise broadly framed term, the ‘British Poetry Revival’ (see note 29) — see Robert Sheppard, The Poetry of Saying: British Poetry and Its Discontents, 1950-2000 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), pp. 142-70 — the term is used here in a broader sense to include international (as well as British) innovative, and experimental poetries, such as the US Language School, that are concerned with the material and systemic properties of language. These poetries are generally construed as alternative to the mainstream of poetry in their respective cultures.

[xvii] Tyrus Miller, ‘Brakhage’s Occasions: Figure, Subjectivity, and Avant-Grade Politics’, in Stan Brakhage: Filmmaker, ed. by David E James (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), pp 174-95.

[xviii] Stan Brakhage, Brakhage Scrapbook: Collected Writings 1964-1980, ed. by Robert A. Haller (New York: Documentext/McPherston, 1982), p. 115.

[xix] Edward S. Small, ‘Motion Pictures, Mental Imagery, and Mentation’, Journal of Moving Image Studies, Vol 1, no 2 (2002) http://www.uca.edu/org/ccsmi/jounal2/ESSAY_SMALL.htm [accessed 10 April 2009].

[xx] Fred Camper, ‘Brakhage’s Contradictions’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48, pp. 69-96 (p. 76).

[xxi] Stan Brakhage, quoted in Suranjan Ganguly, ‘Stan Brakhage – The 60th Birthday Interview’, Film Culture, 78 (summer 1994), 18-38 (p. 26).

[xxii] P Adams Sitney, ‘Tales of the Tribes’, p. 107.

[xxiii] Stan Brakhage, ‘Poetry and Film’, in essential brakhage (New York: Docuentext/McPherston, 2001), pp. 174-91 (pp. 176-77).

[xxiv] Michael Nyman, Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 26.

[xxv] Lawrence Upton, ‘Introduction’, in Word score utterance choreography (London: Writers Forum, 1998), unnumbered pages.

[xxvi] cris cheek, ‘2 experiments – (i.e outcome unknown)’, in Word score utterance choreography, unnumbered pages.

[xxvii] Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, p. 75.

[xxviii] Howard Slater, ‘The Spoiled Ideals of Lost Situations — Some Notes on Political Conceptual Art’, Infopool, 2 (2000) http://www.infopool.org.uk/hs.htm [accessed 10 April 2009].

[xxix] ‘The British Poetry Revival’ is a term attributed initially to Tina Morris and Dave Cunliffe, and adopted by such figures as Eric Mottram, Ken Edwards, Gavin Selerie, and Barry McSweeney to describe what Ken Edwards called:

an exciting growth and flowering that encompasses an immense variety of forms and procedures and that has gone largely unheeded by the British literary establishment [,]

and Gavin Selerie spelt out ‘in oppositional terms’ in the following way:

As various reviewers have pointed out, the 1960s and 1970s actually witnessed an explosion of poetic activity, which was in itself a reaction against the full common-sense politeness of the ‘Movement’ poets of the 1950s. After a period dominated by such figures as Philip Larkin, qualities of inventiveness, passion, intelligence entered once again into British verse. Poets as diverse as Lee Harwood, Tow Raworth, Roy Fisher, and Tom Pickard exhibited a toughness and also a splendour that were entirely absent from the writing collected in the Movement anthology New Lines (1956).

— see Sheppard, The Poetry of Saying: British Poetry and Its Discontents, 1950-2000, pp. 35-76.

[xxx] Stanley Fish, ‘Interpreting the Variorium’, Critical Inquiry, Volume 2, Number 3 (1976), pp 465-86.

[xxxi] Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

[xxxii] Lee Harwood, ‘Lee Harwood — Eric Mottram: A Conversation — 9 October 1972’, Poetry Information, 14 (1975-76), p. 11.

[xxxiii] Aodhán McCardle, ‘Visuality: The Visual Condition; an Other Articulacy of Knowing; trying to speech the unsayable, the inlanguagable’, in The Salt Companion to Lee Harwood, ed. by Robert Sheppard (Cambridge: Salt, 2007), pp. 207-25 (p. 207).

[xxxiv] Lee Harwood, Collected Poems (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2004), p. 414.

[xxxv] Harwood, Collected Poems, p. 10.

[xxxvi] Lee Harwood. The Chart Table: Poems 1965 — 2002. CPRC Birkbeck/Rockdrill. 2004. CD. track 14.

[xxxvii] Lyn Hejinian, ‘Two Auckland Talks’, Essays, New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre (2002) http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/misc/hejinian1.asp [accessed 10 April 2009].

[xxxviii] See Ying Kong, ‘Cinematic Techniques in Modernist Poetry’, Literature Film Quarterly, Vol 32, No. 1 (2005) for more on modernist poetry and cinematic technique. Also Thomas Burkdall, Joycean Frames: Film and the Fiction of James Joyce (New York: Routledge, 2001) more specifically in relation to Joyce, and Max Nänny, Ezra Pound: Poetics for an Electric Age (Bern: Francke, 1973) more specifically in relation to Pound.

[xxxix] see his essays ‘The Poetics of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E’, in Poetics Talks (Calgary: housepress, 2001), ‘Praxis: A Political Economy of Noise and Informalism’, in Close Listening: Poetry and the Performed Word, ed. by Charles Bernstein (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), ‘Poetry as Explanation, Poetry as Praxis’, in The Politics of Poetic Form: Poetry and Public Policy, ed. by Charles Bernstein (New York: Roof, 1998), and his Paradise & Method: Poetics & Praxis (Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press, 1996), for example.

[xl] Bruce Andrews. LINEbreak Program. Martin Spinelli, Producer. Charles Bernstein, Host and Co-Producer. Granolithic Productions. 1996. http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/linebreak/programs/andrews/. [accessed 10 April 2009].

[xli] Bruce Andrews, I Don’t Have Any Paper, So Shut Up (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1992), p. 241.

[xlii] Bruce Andrews, Give Em Enough Rope (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1987), p 59.

[xliii] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. by Colin Smith (London: Routledge, 1995), p. 412.

[xliv] Bruce Andrews, ‘Movement/Writing//Writing/Movement’, in Ex Why Zee (New York: Roof Books, 1995), pp. 15-16.

[xlv] Redell Olsen, ‘Images After Errors/Errors After Images : Joan Retallack’, How2, vol 1, no. 7 (Spring 2002) http://www.asu.edu/pipercwcenter/how2journal/archive/online_archive/v1_7_200/current/readings/olsen.htm [accessed 10 April 2009].

[xlvi] Joan Retallack, Afterrimages, (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1995), p. 7.

[xlvii] See Benoît B. Mandelbrot, The Fractal Geometry of Nature (New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1982) for more on fractal relationships, and the significance of scale invariance in Chaos Theory.

Andrews, Bruce, Ex Why Zee (New York: Roof Books, 1995).

———. Give Em Enough Rope (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1987).

———. I Don’t Have Any Paper, So Shut Up (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1992).

———. LINEbreak Program. Martin Spinelli, Producer. Charles Bernstein, Host and Co-Producer. Granolithic Productions. 1996. http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/linebreak/programs/andrews/.

———. Paradise & Method: Poetics & Praxis (Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press, 1996).

———. ‘Poetry as Explanation, Poetry as Praxis’, in The Politics of Poetic Form: Poetry and Public Policy, ed. by Charles Bernstein (New York: Roof, 1998), pp. 23-44.

———. ‘Praxis: A Political Economy of Noise and Informalism’, in Close Listening: Poetry and the Performed Word, ed. by Charles Bernstein (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp.73-85.

———. ‘The Poetics of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E’, in Poetics Talks (Calgary: housepress, 2001).

Brakhage, Stan, Brakhage Scrapbook: Collected Writings 1964-1980, ed. by Robert A. Haller (New York: Documentext/McPherston, 1982).

———. ‘Chicago Review Article’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 38-41.

———. ‘Encounter: Brakhage on Brakhage — part 2’. By Brakhage: an anthology. The Criterion Collection. 2003. Disk 1. CC1590D.

———. essential brakhage (New York: Docuentext/McPherston, 2001).

———. ‘Stan Brakhage to Robert Duncan & Jess Collins’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 11-24.

Burkdall, Thomas, Joycean Frames: Film and the Fiction of James Joyce (New York: Routledge, 2001).

Camper, Fred, ‘Brakhage’s Contradictions’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 69-96.

cheek, cris, ‘2 experiments – (i.e outcome unknown)’, in Word score utterance choreography (London: Writers Forum, 1998).

Elder, R. Bruce, ‘Brakhage: Poesis’, both in Stan Brakhage: Filmmaker, ed. by David E James (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), pp. 88-106.

———. The Films of Stan Brakhage in the American Tradition of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1998).

Fish, Stanley, ‘Interpreting the Variorium’, Critical Inquiry, Volume 2, Number 3 (1976).

Ganguly, Suranjan, ‘All that is Light: Brakhage at 60’, Sight and Sound, n.s. 3, no. 10 (1993), 20-23.

———. ‘Stan Brakhage – The 60th Birthday Interview’, Film Culture, 78 (summer 1994), 18-38.

Garfield, Eugene, ‘Chronobiology: An Internal Clock for All Seasons’ (Parts 1 & 2), Essays of an Information Scientist: Science Literacy, Policy, Evaluation, and other Essays, Vol:11 (1988).

Grauer, Victor A, Montage, Realism and the Act of Vision, (1982) http://doktorgee.worldzonepro.com/MontageBook/MontageBook-intro.htm.

Harwood, Lee, Collected Poems (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2004).

———. ‘Lee Harwood — Eric Mottram: A Conversation – 9 October 1972’, Poetry Information 14 (1975-76).

———. The Chart Table: Poems 1965 -- 2002. CPRC Birkbeck/Rockdrill. 2004. CD.

Hejinian, Lyn, ‘Two Auckland Talks’, Essays, New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre (2002) http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/misc/hejinian1.asp.

Hill, Jerome, and Guy Davenport, ‘Stan Brakhage and His Songs’, Ubuweb, Ubuweb:Papers, http://www.ubu.com/papers/hill_davenport-brakhage_songs.html.

Iser, Wolfgang, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

James, David, ‘The Film-Maker as Romantic Poet: Brakhage and Olson’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Spring, 1982).

Kong, Ying, ‘Cinematic Techniques in Modernist Poetry’, Literature Film Quarterly, Vol 32, No. 1 (2005).

Lefebvre, Henri, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, trans. by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore (London: Continuum, 2006).

McCardle, Aodhán, ‘Visuality: The Visual Condition; an Other Articulacy of Knowing; trying to speech the unsayable, the inlanguagable’, in The Salt Companion to Lee Harwood, ed. by Robert Sheppard (Cambridge: Salt, 2007), pp. 207-25.

McClure, Michael, Meat Science Essays, (San Francisco: City Lights, 1963).

———. ‘Scratching the Beat Surface’, in Scratching the Beat Surface (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1982), pp. 1-112.

McClure, Michael, and Steve Anker, ‘Realm Buster: Stan Brakhage’ in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 171-80.

Mandelbrot, Benoît B., The Fractal Geometry of Nature (New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1982).

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. by Colin Smith (London: Routledge, 1995).

Miller, Tyrus, ‘Brakhage’s Occasions: Figure, Subjectivity, and Avant-Grade Politics’, in Stan Brakhage: Filmmaker, ed. by David E James (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), pp 174-95.

Nänny, Max, Ezra Pound: Poetics for an Electric Age (Bern: Francke, 1973).

Nyman, Michael, Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Olsen, Redell, ‘Images After Errors/Errors After Images : Joan Retallack’, How2, vol 1, no. 7 (Spring 2002) http://www.asu.edu/pipercwcenter/how2journal/archive/online_archive/v1_7_200/current/readings/olsen.htm.

Phillips, Rod, "Forest Beatniks” and “Urban Thoreaus": Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Lew Welch, and Michael McClure (New York: Peter Lang, 2001).

Retallack, Joan, Afterrimages, (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1995).

Sheppard, Robert, The Poetry of Saying: British Poetry and Its Discontents, 1950-2000 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005).

Sitney, P Adams, ‘Tales of the Tribes’, in Stan Brakhage: Correspondences, Chicago Review, 47/48 (Winter 2001/Spring 2002), pp. 97-132.

———. Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943-2000, 3rd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Slater, Howard, ‘The Spoiled Ideals of Lost Situations – Some Notes on Political Conceptual Art’, Infopool, 2 (2000) http://www.infopool.org.uk/hs.htm.

Small, Edward S., ‘Motion Pictures, Mental Imagery, and Mentation’, Journal of Moving Image Studies, Vol 1, no 2 (2002) http://www.uca.edu/org/ccsmi/jounal2/ESSAY_SMALL.htm.

Soanes, Catherine, and Sara Hawker, eds, Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English, 3rd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Treisman, Michael, ‘The Perception of Time: Philosophical Views and Psychological Evidence’ in The Arguments of Time, ed. by Jeremy Butterfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 217-46.

Upton,Lawrence, ‘Introduction’, in Word score utterance choreography (London: Writers Forum, 1998).