| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 23 printed pages long.

It is copyright © John Latta and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/latta-blog.shtml

John Latta is the author of Breeze (University of Notre Dame Press, 2003) and Rubbing Torsos (Ithaca House, 1979).

You can visit his blog at http://isola-di-rifiuti.blogspot.com/

Paragraph 1

Isn’t it one of the perennial (impossible) reveries of art to return things to thing-hood and beings to being-hood, stripped of any human (cultural) décor or use or encrustation? Such a dream haunts Devin Johnston’s Creaturely and Other Essays (Turtle Point Press, 2009)―signal’d by an epigraph out of David Malouf’s An Imaginary Life, “The creatures will come creeping back―not as gods transmogrified, but as themselves”―long fermata bass note holding against the high treble passacaglia-work (or understory low-stealth to canopy gymnastics). For Johnston’s means of getting at the nature of beasts creaturely here is roundly (read: solidly, and layeredly, a musical round) digressive: in the spirit of Guy Davenport (capable of assembling and aligning the beams of a lecture―the walling-in accomplish’d in situ―while walking to teach at the University of Kentucky), or of A. R. Ammons, who claim’d “a poem is a walk” (and recalling, too, the terrific finely-observed natural histories of Merrill Gilfillan), Johnston writes:

2

In keeping with the etymology of the word digression, I drafted these essays walking around St. Louis and its environs, where I have lived since 2001. As Henry David Thoreau would say, I acted for a time as self-appointed inspector of thunderstorms and starlings, sycamores and squirrels, making my daily rounds. Weedy species and volunteers―common forms of life, opportunists like ourselves―I took as my particular charge. I sought out their local haunts, imagining what they saw, heard, smelled, tasted, and felt. En route, a poem would often come to mind, my private anthology serving as a wayward field guide to whatever I found. In that sense, the poems quoted here are less objects of study than “equipment for living” (in Kenneth Burke’s phase).

3

So one is offer’d wondrous randoms through things like animal senses of smell (starring the dog Chester), urban crow gang behaviors, how birds see “hues entirely unknown to us,” mouse riddance (and the Cretan “Apollo Smintheus, mouse god”), and owl ossuaries. Each essay, with modesty and patience―that is, with consummate deliberation, without flaunting one’s lore―assembles and concatenates a marvelous set of tidbits into a prose condensery (Lorine Neidecker’s word, there is a kinship between Johnston’s decant’d and finely-alloy’d prose and Neidecker’s late pieces). Along the way, one finds quoted apt penetralia out of writers as various as Robert Adamson, James Thomson, Emerson, Yeats, Basil Bunting, Marianne Moore, Robert Burns, Tom Pickard, Chapman’s Homer, Jane Harrison, Aidan Higgins, and Coleridge (“A dunghill at a distance sometimes smells like musk, and a dead dog like elder-flowers.”) There’s a piece at the end of Johnston’s “Murmurations” (about starlings―present in North America only because Shakespeare had Hotspur, in Henry IV, say he’d have “a starling shall be taught to speak / Nothing but ‘Mortimer’” and nearly three centuries later “A drug manufacturer named Eugene Schieffelin decided that New York should be home to all the songbirds mentioned in Shakespeare and joined the American Acclimatization Society for that purpose”―resulting in the late nineteenth century release of half a hundred breeding pairs into Central Park) where an enormous shifting flock of starlings descends to become “a concentrated darkness in the oak limbs,” and Johnston’s own essayistic meander and mustering method seems spell’d out in the murmuration’s collective self-organizing banter and rustle and squawk, its “pastiche of motifs”:

4

The starlings begin a dusk chorus, condensing all they have heard of relevance or curiosity. Just as dreamwork transforms the body’s stimuli and residues of desire, the birds’ song sifts the ambience of this day. Their chorus accrues much that we will never hear, learnt from unpopulated grain fields, parking lots, and unlivable spaces that we have built. It rises to a great cacophony against the last light before diminishing.

5

One motif that recurs in the essays: the liminal, the border, any division between inner and outer, home and away (or two fields, all that activity in the demarcating hedgerow between). In “Mouse God,” Johnston reports finding (one winter night in a St. Louis kitchen) “a deer mouse frozen in panic on the floor, forefoot suspended midstride,” and reflects: “The sudden manifestation of this creature―tiny yet intense―carried an uncanny charge. Unheimlich, the German for ‘uncanny,’ literally means ‘unhomely,’ something from outside that has crept indoors.” Elsewhere, in “Specific Worlds,” Johnston refers to biologist Jakob von Uexküll’s model of particularly “creaturely” scales (“We are easily deluded into assuming that the relationship between a foreign subject and the objects in his world exist on the same spatial and temporal plane as our own relations with the objects in our human world”), and writes:

6

More than mere organism, an animal gets constituted in its essential activities of perceiving and doing. . . . von Uexküll describes the organized experience of a particular creature as its Umwelt, a German compound meaning “a surrounding world” or “milieu.” . . . The Umwelt . . . is not a shared environment but an entirely subjective, phenomenal world. We can enter the Umwelt of another creature―its particular world of time and space, cause and effect―only through imaginative forays.

7

And there Johnston―rather like that deer mouse, “forefoot suspended midstride,” moves to consider the etymology of foray, and uses its “roots in foraging” to move off in a fine mode of aimlessly considering.

8

Particularly enjoyable, the recurrent (and various) references to classical writings and myths, making casually wise and “homely” connections. Here’s that mouse god and its appearance in George Chapman’s translation of The Iliad:

9

Apollo Smintheus remains familiar to us through the Iliad. At the epic’s opening, Agamemnon enslaves the beautiful daughter of Chryses, priest of the mouse god, and refuses any ransom. Chryses prays,

10

O Smintheus, if crownd

With thankfull offerings thy rich Phane I ever saw, or fir’d

Fat thighs of oxen and of goates to thee, this grace desir’d

Vouchsafe to me: paines for my teares let these rude Greekes repay,

Forc’d with thy arrowes.

11

Smintheus answers this prayer after the manner of rodents, spreading through the Greek army a plague transmitted on the tips of his arrows. In Chryses’s temple, nearly a thousand years after the fall of Troy, Scopas carved Apollo with a mouse beneath his foot. Coins from the region depict the god cupping the little creature in his hand.

12

And, because writing is something of a braid or fabric of seeings, I find myself perfectly enchant’d by Johnston’s working together (in “Second Sight”) into a single piece of bright cloth, notes about the seventeenth-century Scottish minister and seer of fairies Robert Kirk, author of The Secret Commonwealth, an account of fairy life record’d, the suggestion is, by one of “hypersensory vision” (“Some have bodies or vehicles so spongeous, thin, and defaecat that they are fed by only sucking into some fine spirituous liquor that pierces like pure air and oil”), along with Robert Hooke of the marvelous Micrographia and William Blake. Johnston:

13

According to Kirk, the senses of these refined spirits are attuned to vibratory hints of distant events, even those yet to occur. In this respect, they share with animals the intuitive powers that we have lost:

14

As birds and beasts, whose bodies are much used to the change of the free and open air, foresee storms, so those invisible people are more sagacious to understand by the Book of Nature things to come than we who are pestered with the grosser dregs of all elementary mixtures and have our purer spirits choked by them.

15

Like the fairies themselves, “men of second sight” and seers of fairies have a spectral sensitivity that surpasses “the ordinary vision of other men.” They witness the hidden world through improvements “resembling in their own kind the usual artificial helps of optic glasses (as prospectives, telescopes, and microscopes).” Robert Hooke, the father of microscopy and a close contemporary of Kirk, argues in Micrographia that such instruments might compensate for the human loss of both sensory perfection and Adamic knowledge. A century later, William Blake conceived of our fall from full sensory awareness in similar terms. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he tells us that the senses were “enlarged and numerous” until contracted into five: “for man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”

16

Another way by which unobstruct’d full human knowing of things and creatures is quash’d.

Hans Holbein the Younger, “A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling,” c. 1526-8

17

Creaturely is a terrific book, exquisitely design’d by Jeff Clark (an enigmatically crop’d full-bleed detail of Hans Holbein the Younger’s early sixteenth century painting, A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling graces the cover).

18

A YEAR

CXLVI

A method coughs

up its loud

caucus and succumbs

to mannerist hair-

splitting: the sun

clangs down reverberant

like a big

brass cymbal, its

width precisely that

of the length

of Prester John’s

foot. All night

I dog-trot

the Asian periphery,

olive drab clad,

scooping up scolds

of rust’d dog-

tags in bazaars.

If art is

the conquistador of

naught, why flank

it with imperial

gusto? It commemorates

everything or nothing,

marshals itself against

the trudge-particular

dudgeon of high

martial music and

its inveterate squad

or company: art

patrols no edge.

Out of green

jungle and ‘unwholesome

fen,’ the wound-

sucking sun pulls

clamor and rot

twinning cancerously, strips

art’s radiant carcass

inch-meal clean.

# posted by John Latta # 5:45 AM

19

A YEAR

CXLII

Here (doubtless passéiste sloganeering)

is my bullying counter-

command apropos of loud-

speakers: that you refuse

to allow any (agreeable,

benign, simpatico, or just)

to speak for you.

Authority (and hierarchy) loves

a designee, a mouth-

piece, and a glare,

whereas ‘a smattering of

prebends rends Scripture itself.’

(In unlit medieval Paris

anybody out at night

had to identify himself

by carrying a light.)

Bachelard: ‘The lonely dreamer

who sees himself being

watch’d begins to watch

the watcher. Hiding one’s

own lantern exposes the

lantern of the other.’

Ah, the brute whelm

of dispersal, the hang-

dog intimacy of base

surveillance! (Melville instruct’d Hawthorne:

‘go to the Soup

Societies.’) What I mean

is, be one who

unendingly disembarks, one who

mans a spectre-boat

in a loudening gay

flotilla, keeping the security

apparatus and engine nervous

(with its uncanny representations

of men), ‘a process of counter-

surveillance trigger’d everywhere a

surveillance lantern is lit.’

20

Splay and angst (a general condition). I paw the pristine (invariably, it is a book), trying to consume it. The balance, the tidy of it, compels and mocks: how-lock’d down and impeccable it is! How nail-bit and distract’d am I! Counter-clock’d cart-wheeling eye activity unleash’d on cue. Wood rasp roughing up the oily brain-lobes. A palsy and wobble of thinking loos’d like the belt-slipping squeak-chatter of a chipmunk, who finally streaks off with its tail stuck straight up, a one-idea man, like a man with a sandwich-sign.

21

Reading (finally, cavalcade and uproar of fidgeting subsiding) a little of Philip Lopate’s new Notes on Sontag (Princeton University Press, 2009), inaugural number of a series of “Writers on Writers.” The sufferance of the essayist in a (compensatory) world of novelists:

22

I, who revere the art of essay writing, and who can never regard literary nonfiction as even a fraction inferior to fiction, find puzzling Sontag’s need to be thought primarily a novelist. But not unusual: postwar American writing featured a number of writers arguably better at nonfiction who preferred to be thought of as novelists: James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy, Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote. Novels were considered the Big Game, essays the minor pursuit.

23

(And poetry? Only the foolish hunt the “queenly” poem―its reward is cachet, that majestic seal, pizzazz, what, one supposes, we now call “cultural capital.” One suspects the poet who “turns” novelist of some baser grub-instinct.) What Lopate’s book allows (in its notational, digressive way): a way of looking at Sontag’s contradictory moves. In “Thirty Years Later . . .,” a piece reconsidering her own 1966 classic, Against Interpretation, that she publish’d in The Threepenny Review in 1996, she says “My idea of a writer: someone who is interested in everything,” and (as Lopate notes) “rues what she sees as the present moment, as ‘age of nihilism.’” Lopate: “while loyal to the Sixties, her honesty forces her to consider that its irreverence may have planted the seeds for the undermining of seriousness, while ‘the more transgressive art I was enjoying would reinforce frivolous, merely consumerist transgressions.’” Not that Sontag is assuming blame. She says:

24

Writing about new work I admired, I took the canonical treasures of the past for granted. The transgressions I was applauding seemed altogether salutary, given what I took to be the unimpaired strength of the old taboos. The new work I praised (and used as a platform to relaunch my ideas about art-making and consciousness) didn’t detract from the glories of what I admired far more.

25

And, later: “To call for an ‘erotics of art’ did not mean to disparage the role of the critical intellect. To laud work condescended to, then, as ‘popular’ culture did not mean to conspire in the repudiation of high culture and its burden of seriousness, of depth.” Which sayings inevitably require that I thump a little at “the age” (as I am wont, for at heart, “at heart I am an American moralist and I have no guilt,” as Patti Smith nearly said . . .) in its shallower manifestations (see the maximum gagas of FlarfCo® and company), recalling how, even in the original pages of “Against Interpretation,” even with its puckish Wildean epigraph “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances,” Sontag is clear: art’s job is refusal, the refusal to be buffalo’d by sheer consumptive ardor, mere fatting up on hilarity like medieval grotesques:

26

Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience. All the conditions of modern life―its material plenitude, its sheer crowdedness―conjoin to dull our sensory faculties. . . .What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more. Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.

27

As Lopate puts it: “style as morality” is one of Sontag’s recurring concerns. As Sontag says in “On Style”:

28

All great art induces contemplation, a dynamic contemplation. However much the reader or listener or operator is aroused by a provisional identification of what is in the work of art with real life, his ultimate reaction―so far as he is reacting to the work as a work of art―must be detached, restful, contemplative, emotionally free, beyond indignation and approval.

29

That, against excess, formal or contentual. Lopate, recalling how Sontag’d approvingly quoted Jean Genet’s line that if his works arouse readers sexually, “they’re badly written, because the poetic emotion should be so strong that no reader is moved sexually. Insofar as my books are pornographic, I don’t reject them. I simply say that I lacked grace,” insists that

30

. . . grace is all, in Sontag’s cult of art. Sontag remains on some level a classicist, an Apollonian, embracing balance and harmony. Perhaps there is no contradiction here, like the teacher who writes on the blackboard in Godard’s Bande à Part, “Classique = moderne.”

31

―

32

Steve Evans is putting up the 2008 Attention Span. [At: http://thirdfactory.wordpress.com/2009/04/29/attention-span-2008/] Select’d books that dogged or compell’d somehow, territorial marks of the preceding year or so with a clinging whiff. I stuck to poetry [http://thirdfactory.wordpress.com/2009/05/21/attention-span-john-latta/].

# posted by John Latta # 6:26 AM

Red Palm

33

A YEAR

CXLI

How about some operatic mewling:

how the completely feasible―cost-

efficacy a must―dry storage

and continual delivery of sheer

gaseousness awaits its Edison, though

compression canister-bombs en forme

de l’écriture « post-Idlewildienne » allow

a limit’d work-around. Like

changing one’s name for art!

van de Beeck to Torrentius!

Every affair develops on two

planes (and ends up in

an airport lounge, surround’d by

a forest of giant bamboos

mold’d out of recycled truck

tire Ho Chi Minh sandals).

Tango Uniform Victor Whiskey. I

think you know the story

of the feeble Dutch medical

student by the name of

Jan Swammerdam with the mania

for insect life. Bee-stung

lips, veins crawling with ants,

he shat out black beady

heaps of Coleoptera. There is

no end of human folly.

How I loved seeing brick

factories―so artisanal!―in Mexico.

“And then we towel’d each

other off and dash’d out

nakedly, into the green rain.”

34

Hunh? Off I went hier soir to see mezzo-soprano Elīna Garanča in the Metropolitan Opera’s recent do (record’d “live in HD”) of Rossini’s La Cenerentola, a version of the Cinderella story, liking particularly the broad comedic moves (think of Art Carney) and impeccable timing of Alessandro Corbelli (who play’d Don Magnifico), irreparably addled by the ongoing reverie of marrying off one of the two haughty daughters―gawky, horse-faced Clorinda (Rachelle Durkin) and Tisbe of the pinch’d snout (Patricia Risley)―to the princely Don Ramiro (Lawrence Brownlee). Garanča: mischievous, exquisite, and capable of singing tremendous soaring runs and flights of notes nigh-effortlessly, without any sign of temperamental vanity, recalcitrance, or any of the freights of the prima donna-ish. One question (ask’d in mighty and resonant basso profundo): how come the tenor always ends up with the girl?

# posted by John Latta # 6:08 AM

35

A YEAR

CXL

Isn’t Frank O’Hara’s “minute bibliographies of disappointment” akin to

Pound’s “dim lands of peace,” that abstract genitive

Superfluous and dulling, spooning off adequacy? Though I think

O’Hara’s putting it to Ezra’s patootie a little when he says in “Personism”

How “the decision involved in the choice between ‘the nostalgia of

The infinite’ and ‘the nostalgia for the infinite’ defines

An attitude towards degree of abstraction.” I think he’s harrumphing

Out with a little malicious glee there, something he did with the ease

Of a gasp. When he plow’d through Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio

Medici (juggling a tumbler of gin and a Camel cigarette, sunk down

Slouch’d in a canvas butterfly chair) and noted “when I

Survey the occurrences of my life and call into account the finger of God,

I can perceive nothing but an abyss and mass of mercies,” he leap’d

Up like a rodomontade knocking the philodendron alee to write

That thing about the “natural object” of church Sundays and The

Finger.

36

Truth is, in my own “parade / of a generalized intuition” (how I “judge” the poetry-beasts that trundle down the thoroughfares dropping hot steaming turds of a maniacal variety of inconsistency), Chris Nealon’s Plummet is nigh-terrific. He works a supple long line (“I know prose is a mighty instrument but still I feel that plein-air lyric need to capture horses moving” he writes in “Poem (I know prose . . .)”) and, in a world seemingly divided between the jaunty and the raunchy (and no Mark Twain mete enough to refuse it all), Nealon chooses both (“Your job? Just keep cracking Demeter up” slides uneasily into “At the gates of Arabic I enter, illiterately // Actually I know two words // shaheed / habibi // I watch depictions of electrocution under bright fluorescent lighting with a slightly elevated heartbeat” into “Do I have an astral body or a tapeworm?”), and provides the humor himself. Nealon’s got verve and wit, and it regulates (without throttling) the underlying political rage of the book. Here’s “Sunrise,” one of the longer pieces in Plummet:

37

―and the felt-tip pen of the spider etches a message on the wall

message in oxygen and light a hand gropes past me―

it says, nothing you read will help you now

not the pig-poetic snuffling behind the image

not the trampled earth behind the sun

helicopter buzzsaw bicycle bell

ignition―

slammed door footfall schoolkids

jets―

the war is on

*

why does universal

matter peddle itself in packets when

we could take it harder?

slight convexity that used to be

the flat screen,

disturbing

flatness that was once

a curved screen,

pleated fabric

on the walls and the movie so unmagical

not the moving image

not the immanent translation

not the hem who touched the hem

*

so noon is when the spoken

and the written touch

in chants, in shouts―

and the ease in your voices

and the glottal struggle in your voices

and the cryptogrammatic slur

all touch―

glyph of the beautiful

Molotov-thrower

throwing a bouquet

glyph of the black flag

held aloft in schools

*

now into walls of fortresses

across the strange black vinyl of the shitting-stalls

on the lenses of the egrets poised above the freeway

with the edge of an Xacto

they carve SUNRISE

a shaft of it in shopping carts

the motes of it around their ears

matter itself now hauled in plastic bags to the Federal Building and mixed there

with water and a little food dye

by the scrawl on the sidewalk that reads Go Ahead Honey Touch It

*

we’re here to puke in many colors―

elf-puke, witch-puke, giant-puke

disco puke and punk puke

vomit on the apron of the government

vomit on the boots of the police

it’s January 17, 1991

it’s March 20, 2003

It’s morning

Puke and sing

38

(The dates, obviously, of the beginnings of “our” two illegal and preemptive incursions―wars―against the sovereign state of Iraq.) If the piece begins in medias res and in writing (“felt-tip pen”), that never-casual and unceasing thing, it also begins with a terrible helplessness, the minuscule “spider.” (Recall “new forms of compositional helplessness”―the writer in / against the state is equivalent to “pig-poetic snuffling,” air, and theory.) I like how quickly human and local the cacophony of noises becomes: “helicopters” to “bicycle bells” to “schoolkids”―the beginning of the war’s got all the everyday nonchalance of an ice cream truck toodling by, against which―is it the academical self who’s indict’d?―“nothing you read will help you now.”

39

In the second section of “Sunrise”: a tiny jagged essay on the varieties of screening (screening off, screening in order to see) by way of television and movie screen shapes and sizes. “Packets” of “matter” (that hardly matters), only its shrinking (and our distance) makes any difference (“we could take it harder,” a lament for the simulacral ease that allows such farce). “Peddle”: the sale of the war, its image made palatable to the public by (or through?) “immanent translation”―that stupid inward glow of the nightly news, its acceptable drone, no hem (of stage curtain, of actress’s skirt): we’ve not even the chamber’d proximity of “live” theatre.

40

Three. Is “noon” akin to “high noon,” that old Western confrontational convention? If Nealon’s writing (partly) about the efficacy of the written word versus what, mobilization of bodies? the protesting crowds of the manif? speech? is it here that some rejection of writing occurs? Why “your voices”―that distance? Still: the physical world―the “cryptogrammatic slur // all touch―” fails, too, and becomes mere “glyph” (and glyphs out of a rather Hollywoodish, popular imaginary, “Molotov” and “black flag” cartoonishly dispelling even the “ease”-reality of any crowd).

41

Four. Another parable of writing. Sunrise itself turn’d to writing of a particularly vivid and rather gruesome kind. That “Xacto” recalling, one supposes, the “box cutters” of the “shahid” (martyr, witness; plural, apparently, šuhadā) of September 11. Writing become a kind of vandalism (“shitting-stalls”), not even the natural world (“egrets”) exempt, the “all touch―” tiny dream of communitas reduced to a slovenly plea: “Go Ahead Honey Touch It,” whilst something slightly ominous and “Federal” is done to the war “matter” (plastic bags evoking body bags?)

42

The paroxysms of puke in the final section occur, then, against a backdrop of the uselessly writ, the ineffectual―(I want to say the consciousness itself colonized by image-production, glyph’d-out). Against such helplessness, writing reduced to crude “carvings,” thwart’d and contain’d: illness and refusal, and the bodily joy of rebellion. Puke-music. Is it a form of infantilism? Probably. I did find some remarks that Nealon made about “Sunrise,” apparently for a class of Brenda Hillman’s. He refers to it as “that embarrassing thing, a political poem,” and continues:

43

―or, worse, a “topical” poem, involved in the recent war; in particular, it’s a poem trying to understand what kinds of writing and speech war generates, or captures. Basically I found myself, in March, thrown unexpectedly, in my political anger, into a kind of glyphic mode of seeing and reading: back in March, things―like events, and actors, as well as material objects―for a while things seemed both legible and conceptual to me, on the one hand, and like blunt, brute stuff, on the other. And somehow this seemed like the effect of the political situation.

44

So I thought I’d test out, from the vantage of witnessing mostly, what it meant to live through a moment glyphically, to stumble between the articulate and the inarticulate facets of outrage and hope. One way of thinking about how the “form” of the poem tries to do this, then, is to think of the five sections as offering different approaches or occasions for this glyphic outlook. First, as a kind of epiphany; second, in a humbling recognition that the distribution of images or narrative (I’m at the movies in this stanza I guess) is off-kilter; third, in the realization that sometimes the way to grasp both aspects of the glyph is in a “moment”: in a chance: when things congeal: as when people’s togetherness, all at once, works. The fourth section presses on that a bit, to imagine the activity of politics-as-“writing” as distributed across space, not just trapped in that one flash-place where a political demonstration is taking place; and the last section, with the “we,” imagines grappling with political meaning as a comic mismatch between the articulate and the inarticulate, in vomit, that un-formal thing.

45

One final piece, sans commentaire, because I admire it, its variable antics and celebratory / consolatory swagger / limp:

46

Caressed

The body is amazing

You could just decide, I want really strong ankles

Various plastic and rubber devices can be used to train it

A movement of the limbs can say, this is how much space there is in business for

charisma

Leather Nikes in the 90’s, signifying triumph over technical obstacles

“It also has that wet look”

Depending on your nationality, your body can be “packed in ice and wrapped

in cellophane”

I may or may not be able to find it

Packed dance floors in slow motion / everybody on their cell

The body “has been announced so many times that it cannot occur”

But it comes to life in carnival situations

It is capable of feelings incommensurate with personhood

From the pagan version it has gone from being sculpture to being vector, but for what

Dashed hopes in the little Parthenon

Karaoke glory and “a touch of the gai savoir”

When the body goes limp so limps the world

Soft as the slug’s antenna

Though my hair turn white I will not harden against it

# posted by John Latta # 5:41 AM

Chris Nealon’s Plummet (Cover by Liliane Lijn, “Waveguide: a counterpoint in 15 parts,” 1977-78; Design’d by Justin Sirois)

47

Disconcerting―and possibly “wrong,” though I only detail a trajectory―to open Chris Nealon’s Plummet (Edge, 2009) and see its epigraph (“―yet leave the tower”) and be swell’d momentarily along some populist gamut by lines (in the first piece, “Jackhammer Namaskar”) like: “I want to send a message to the multitude / I want to spread beatitude but the animals are afraid of me.” One readjusts for “tone” and (eventually) figures out that Nealon’s “plummet” is less a rejecting of the long-chided ivory tower with its fickle scholiasts, than it is Hart Crane’s “plummet heart” out of “Recitative” (with all the declamatory ambivalence toward the ordinary that poet employ’d, and that title recalls). Crane:

48

Then watch

While darkness, like an ape’s face, falls away,

And gradually white buildings answer day.

Let the same nameless gulf beleaguer us―

Alike suspend us from atrocious sums

Built floor by floor on shafts of steel that grant

The plummet heart, like Absalom, no stream.

The highest tower,―let her ribs palisade

Wrenched gold of Nineveh;―yet leave the tower.

The bridge swings over salvage, beyond wharves;

A wind abides the ensign of your will . . .

In alternating bells have you not heard

All hours clapped dense into a single stride?

Forgive me for an echo of these things,

And let us walk through time with equal pride.

49

I want to read it―Plummet in general―as a struggle to talk sensibly about “the age” to “the masses”―or somebody “like” them, I use the word, a terribly weight’d one, unadvisedly, though Nealon himself is prone to touches of revolutionary chic: “glyph of the beautiful / Molotov-thrower / throwing a bouquet // glyph of the black flag”―(for it is inform’d through and through by recent and abominable U. S. history and it keeps nodding in the direction of the radical impossibility of doing so―that is, talking sensibly―without a complexity of register-shifts, both self and “project”-deprecating.) That is to say: Plummet is smart and smart-alecky and fun: it is, too, beleaguer’d precisely by the “nameless gulf” of “no way to say it.” See it in the opening lines of “As If to Say”:

50

So I’m digging these new forms of compositional helplessness

“I bring to this project an immense wind”

I try to write descriptively,

But it all comes out a calligram: check-mark inanition: flicked wrist of creation

the gaming movement of vowel sounds

chorus and apostrophe

Only your prettiness is keeping you free

51

The trouble with such clever knowingness is that it threatens to become mere snottiness (later, the comedy-club Stevensesquerie “I seriously have a mind of winter” is follow’d by “I don’t know it was spring”). It is poetry of the sleight-of-hand man, “pretty,” charged with audacity, and, for all its pump’d brave admittings of “inanition,” rather inane, and so (heartbreakingly, for one dreams of a poetry efficacious enough to make change) “free.”

52

“As If to Say” is not the only example. The preceding piece, “Headless,” reads, in part:

53

―I read your poem as a record of thirst, yes,

but also as a glass of water carried wobbling on a tray the length of the party

I experience your poem as learning to make do with its placement in a super-

organized and mercilessly chaotic arrangement of contracts

I think your poem is hot

. . .

All the jottings in my notebook bore me

But there’s something touching in your little letterpress of capitals and stars

There’s an un-appalling touch of universal truth in watching how you almost

come unbound

So I read your poem as a fumbling virtuoso throwing up of hands

There is no flag for its emotion but it has songs

54

That natural sass and fluidity of line recalls O’Hara (Nealon: “You pray: // I want / To be O’Hara / Lord, but it’s / Duncan where / We’re headed”―though one encounters none of Duncan’s pinch’d-to-fit esoterica here, or tendency to bombast). If the poetry loudly doubts its own efficacy, it does so with a wink and a nudge, wisecracking and promiscuous (I want to make a claim that it “falls” to something akin to “keeping the coterie amused”). (Not a quarrel with coterie-poetics, a quarrel with the dispatch of, say, the Iraq war to coterie-inflect’d ironies. See something like “Period Piece,” with lines like “the letter is the form in which the literary can still smile” or “I tried to write you sonnets but they sounded courtly” or “For your sake now I ignore the war, though I hope you will teach me the Latin for torture,” and ending―too knowingly caustic―with “Continue to love me. Send us your army.”) Fiddling whilst Rome burns? At its worst, it partakes of the empty-hand’d gaming of the clown-troupe FlarfCo® product. In poems like “Events and Happenings” (“The system was breaking down and we were lost in the maelstrom / The system was breaking down (which the mathematical theory says must happen) // They still weren’t acknowledging the system was breaking down, not to mention screwing people over and having them banned for life on LIVE, look it up!”), and “A Piece of It” (“The closing passages include Jake’s crisis of pure despair / Nine inches of pure despair // Wrenched into pure despair by a cowering husband, by a duplicitous, vile God, and not being able to afford £30+ for the so-called miracle moisturizers”), and “‘Most Gracious Channel’” (running similar basic data-mining moves on the phrase “this song” and pruning the imprudent―or impugning the impudent, or seeding the insedulous―out of what results), the borrow’d form itself mires down each piece. How quickly the Google-sculpt’d poem’s become an empty form, a shrug unreadable beyond itself, not unlike how WCW noted of the sonnet (though only after some several centuries) that every sonnet says “I am a sonnet”―every Google-sculpt says Google-sculpt. (Williams also noted how “Forcing twentieth century American into a sonnet” is “like putting a crab into a square box,” cutting off the legs to make it fit―a kind of fit image of the parsimonious low slapstick shtick that is FlarfCo®.)

55

“Janus-faced.” It’s in “Recitative” (“Regard the capture here, O Janus-faced, /

As double as the hands that twist this glass.”) And, too, I am thinking of O’Hara’s lines (out of the 1950 “L’Amour Avait Passé Par Là”):

56

a candle held to the window has two flames

and perhaps a horde of followers in the rain of youth

as under the arch you find a heart of lipstick or a condom

left by the parade

of a generalized intuition

it is the great period of Italian art when everyone imitates Picasso

afraid to mean anything

as the second flame in its happy reflecting ignores the candle and the wind

57

Unsuccessfully ignoring the brazen voice of Elton John calling out of that final line and mucking up the O’Hara, I am trying to say that tomorrow a different savage parade’ll go by. And it’s banner’ll likely read: “What I Like about Chris Nealon’s Plummet.”

Chris Nealon

58

A YEAR

CXXXIX

Diaphanous the light

propellant against cranny

and cave. It

dispels drear, rousts

it out like

speech: ‘Who heareth,

seeth not form /

But is led

by its emanation.’

Pound. A shapeliness

sprung of wavelets

slapping a tympanum,

forg’d in that

sanctum wherein pound

hammer and anvil.

Form is musical

or it is

nothing, a sidelong

look, changeable, shredding,

like a loop

of yarn nail’d

up and undoing

itself somewhere within

a distant nook.

# posted by John Latta # 6:59 AM

59

A YEAR

CXXXVIII

Ephemeral, like the caddis-

fly that emerges up

out of its debris-

cover’d sac. Attach’d with

spittle to some down-

river side of rock,

its larval cairn marks

the imago’s hatch, synchronous

and en masse, design’d

for maximum sexual provender.

Oh the social ditties

of the formicary, apiary,

honeycomb, dewy and meagre―

it adds up nothing,

one isn’t the color

of the wood louse

roll’d up the size

of birdshot, one isn’t

the shrike-hung mouse

in the hawthorn tree.

Down in the dead

oak leaves, matted, under-

runnel’d with millipede holes,

the mayapples upthrust, provide

a sudden interrogatory green.

What is the point

of the ongoing cycle,

the abiding render’d stoic

by loss, the prissy

pure convert’d to God-

teeming morbid excess by

loss? The shaky crapulent

hand in the margin

is appraisal and testament.

60

The stretch’d out weekend, reading Larry Heinemann’s 1977 Close Quarters in between bouts with the Goncourt’s Journals. (I like my juxtaposings fatuous.) And dabbled in Daniel Kane’s new thing, We Saw the Light: Conversations Between the New American Cinema and Poetry (University of Iowa Press, 2009), with chapters on Kenneth Anger / Robert Duncan, Stan Brakhage / Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara / Alfred Leslie, and John Ashbery / Rudy Burckhardt, amongst others. Out of it is Stan Brakhage replying to the question “What’s your response to the postmodern aesthetic that seeks to break down the boundary between art and pop culture―in essence, that anything can be art?”

61

Hogwash.

62

With the addendum:

63

Created by a lot of lazy people who want to have their childhood kicks and have it sanctified as it was something tremendously serious. It’s not church-worthy. And they have infiltrated the colleges to an enormous extent where they’re even more pernicious because they know perfectly well that how to become a popular professor is to give all their student the sense that they can have all their easy movies, where they can escape and bug out, while at the same time having a profound art experience. The students lap it up, and both them of serve each other, sitting in lazy land. You know art is a hard pleasure, and that’s the beautiful thing about it. The appreciators are as hard-working as the maker to comprehend and unravel the enigmas and the complexities of a poetic cinema.

64

(Ah, all that whoop’d up Poundian struggle, the drawstring of the Beardsley line to Yeats that is work’d into the hem of the Cantos, “So very difficult, Yeats, beauty so difficult.” Pound:

65

Les hommes ont je ne sais quelle peur étrange,

said Monsieur Whoosis, de la beauté

La beauté, “Beauty is difficult, Yeats” said Aubrey Beardsley

when Yeats asked why he drew horrors

or at least not Burne-Jones

and Beardsley knew he was dying and had to

make his hit quickly

66

The Beardsley who perish’d of tuberculosis at age twenty-five, who aver’d: “I have one aim―the grotesque. If I am not grotesque I am nothing.”) That’s one thing I think, and parry Brakhage’s thrust to make of any art a religion. (Kane himself initially counters the Brakhage with lines out of O’Hara’s “mock manifesto ‘Personism’”―“Nobody should experience anything they don’t need to, if they don’t need poetry bully for them. I like the movies too. And after all, only Whitman and Crane and Williams, of the American poets, are better than the movies,” seemingly putting O’Hara in the “popular culture” camp―a move that may not adequately read the ferocity of O’Hara’s contempt for the assumption of any need to make the distinction.

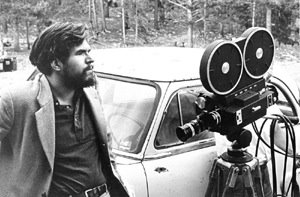

Strips out of Stan Brakhage’s 1963 Film, “Mothlight”

67

The other thing I think: how Brakhage’s lines might well apply to the Flarf / Conceptualist drill squad (whose only discipline, “sitting in lazy land,” is point’d toward the maintenance of tight ranks). Surely the “kicks” available there, if not exactly matching those of one’s childhood, mimic precisely―fatuous juxtaposings front and center again―those of the childhood of the “art.” What if one were to bring the Goncourts into play?―“There have been many definitions of beauty in art. What is it? Beauty is what untrained eyes consider abominable. Beauty is what my mistress and my housekeeper instinctively regard as appalling.” Is that a difficult beauty, or a class’d beauty?

Stan Brakhage, 1933-2003

68

One is, I suppose, caught between rejecting the taint of religiosity, puritanical, the gnash’d teeth art-struggle, and rejecting the hoydens of gaping boorish “humor” at all cost (with its meretricious claims to profundity or “the age.”) Where turn? Nowhere. Vietnam novels. Who cares about beauty anyway? Edmund Burke says “Beauty is . . . some quality in bodies acting mechanically upon the human mind by the intervention of the senses.” Ah, these robotical clods . . . Why are you reading this anyhow?

# posted by John Latta # 6:45 AM

69

A YEAR

CXXXIV

According to the Goncourts,

to whom he shout’d

it whole one day

‘in a stentorian voice,’

Flaubert’s early novel, Fragments

of Unremarkable Style, concern’d

the autochthonous melancholy of

youth unassuaged, even by

an ‘ideal whore.’ Later,

after a plausibly indifferent

meal, one unremark’d in

the Journal, the hermit

of Croisset pull’d out

“oriental trappings,” hoist’d a

red Turkish tarboosh, look’d

with morosity and tenderness

at leather breeches worn

in Egypt: ‘a snake

contemplating skin it’d shed.’

What any writing is.

If the soul of

any other is so

monstrously dark, what hilarity

we muster is a

dodge. So we gird

up repute with stupefying

feints and rent residuals,

sluice convulsedly through howler

unabash’d and wisdom infecund

alike, dropping a word

here, hoisting one up

for assay or proof

there. And out walking,

dog at heel unbid,

recall the imponderabilia of

‘this worldes transmutacioun,’ how

that other, too―the

one jotting cuff-notes

mid-ruckus―’d ‘seyn it

chaungen up and doun.’

70

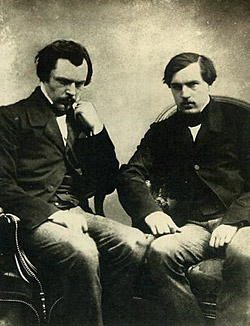

Books invariably pointing to books, ganglionary knots of convergence and divergence: that’s how I end up prancing like a Firbank through the Journals of the brothers Goncourt, Edmond and Jules (in the 1962 Robert Baldick translation and selection, recently reissued, call’d Pages from the Goncourt Journals). Edmond, who lived long after Jules succumb’d to syphilis, prefaces one volume (in 1872) by claiming it “the confession of two twin spirits, two minds receiving from the contact of men and things impressions so alike, so identical, so homogeneous, that the confession may be considered as the effusion of a single ego, of a single I.” Which I find terribly refreshing after all the late twentieth century hoopla and avalanche of the shifting, discursive, unstable, “positioning” self, the common cant of it. “I am half an I.”

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, 1854 Photograph by Félix Nadar)

71

The fun, though, is in the snips of table-talk, the literary sightings. Here’s Baudelaire à table in October 1857 (a couple of months after being fined 300 francs for offending public morals with Les Fleurs du Mal, and having six poems therein suppress’d) at the Café Riche (which “seems to be on the way to becoming the headquarters of those men of letters who wear gloves,” where “none of the guttersnipes of literature would venture”―rather like, say, oh, the Kelly Writers House today―one learns how one “Murger… is rejecting Bohemia and passing over bag and baggage to the side of the gentlemen of letters…”):

72

Baudelaire had supper at the next table to ours. He was without a cravat, his shirt open at the neck and his head shaved, just as if he were going to be guillotined. A single affectation: his little hands washed and cared for, the nails kept scrupulously clean. The face of a maniac, a voice that cuts like a knife, and a precise elocution that tries to copy Saint-Just and succeeds. He denies, with some obstinacy and a certain harsh anger, that he has offended morality with his verse.

73

(The Journals rather casually note how, at a dinner “with Flaubert, Zola, Turgenev, and Alphonse Daudet” at the same café in 1874, “We began with a long discussion on the special aptitudes of writers suffering from constipation and diarrhoea,” which, it occurs, may possibly prove a distinction at least as useful as Ron Silliman’s two scat-heaps of “post-avant” and “quietist.”) (Too, one notes Turgenev’s remark about the limits of the French language: “an instrument from which its inventors expected only clarity, logic, crude and approximate definition, whereas today it so happens that this instrument is being handled by the most highly strung and sensitive of writers, and the least likely to be satisfied with approximations.” Ah, for the days of concerns about precision and intent, about the “reach” of one’s, gulp, lingual tool, something more than the squabbled-up offal of mere “attitude” . . .)

74

Talk with Flaubert and the literary critic Sainte-Beuve about copyright, Sainte-Beuve reacting to someone’s call for “perpetuity of rights”:

75

Sainte-Beuve protested violently: ‘You are paid by the smoke and noise you stir up. You ought to say, every writer ought to say: “Take it all: you’re welcome to it!”’ Flaubert, going to the opposite extreme, exclaimed: ‘If I had invented the railways I shouldn’t want anybody to travel on them without my permission!’ Thoroughly roused, Sainte-Beuve retorted: ‘No more literary property than any other property. There should be no property at all. Everything should be regularly renewed, so that everybody can take his turn.’

76

And the Goncourts (aristos non placables) subsequently see in Sainte-Beuve “the fanatical revolutionary bachelor”: “he seemed at the moment to have the character and almost the appearance of one of the levellers of the Convention. I saw the basic destructive urge in that man who, rubbing shoulders with society, money, and power, had conceived a secret hatred for them, a bitter jealousy which extended to everything . . .” Usual tiresome ploy of the “made” to upstart sneerers, wholly disbelieving that one might not aspire to “making.”

77

Off to remake myself into a half-man (half-biscuit). À Lundi.

# posted by John Latta # 6:44 AM