| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 9 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Christopher Funkhouser and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/damon-by-funkhouser.shtml

Maria Damon; photo by Aldon Nielsen

Paragraph 1

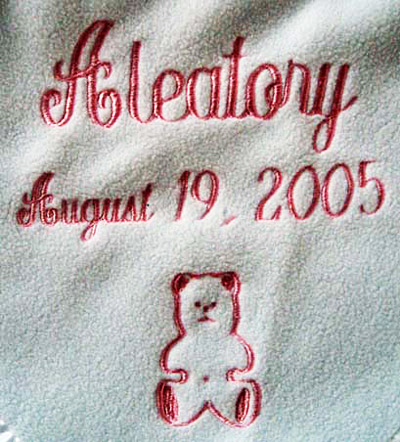

While recognizing them as objects of tremendous beauty, and being aware of her serious (sometimes lettrist) weaving practice, I never thought to “read” Maria Damon’s non-alphanumeric textile-works until she recently inquired if I were somehow able to do so. My shortsightedness! Damon has given three pieces to my wife and me as gifts during the past decade, classically so: for wedding, our first house and child. None of them contain written detail (unlike machine-embroidered blankets inscribed with our children’s names such as those we received from my employer) (see Appendix I). Yet the weaving contains many patterns, expressive coding that offers pause for contemplation and interpretation. In both chaos and repetition, perceivable — if subjective and abstract — narratives or statements are transmitted. The yarn is, literally, spun. To view these things as something beyond attractive domestic artifacts is possible — I just never really did so before now.

2

Having never studied or practiced working with textiles, I know very little about sewing, weaving or knitting, or all of the different decisions that must be made in the process of weaving and securing an object with threads. I have not cultivated the formal language in which to speak articulately about this material, so can most basically state a simple amazement (wonder) at how the designs are formed, how they are held together, and how they manage to bear personality. My understanding of what I am looking at has now suddenly changed, charged with new personal value reflecting a social fabric naturally expanded through Damon’s artifice, in which the language is visual, and the woven patterns are implicit, symbolic.

3

Each member of society decides on her or his own way of communicating feelings, of reflecting the known and the unknown, of exercising authority, enforcing it, and passing all these patterns onto others. So often, in creations by individuals who do needlework, we see very practical or direct purpose. Quilts, rugs, sweaters, and so on, are made to keep people warm, as well as to decorate bodies and homes. Messages are sent through needlepoint proverbs (e.g., “Yours is the Earth and everything in it”), prayers (e.g., “Now I lay me down to sleep… ”), and so on.

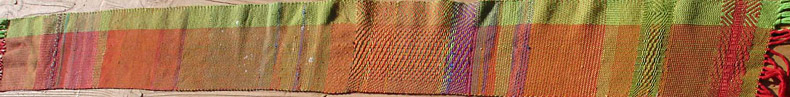

Fig 1. Maria Damon. Wedding shawl, 1998.

4

Damon’s transmissions are much more ambiguous, open, and difficult to define. In Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary N. Katherine Hayles recalls, “the etymology of ‘text’ as ‘knitting’ or ‘weaving’” (72). An inextricable association can be made thus between “the writing” found in texts and textiles, two seemingly different forms. In Damon’s work a sense of text-aisle also emerges in the (by necessity) straight rows that by appearance are series of wobbly, wavering, textured lines.

Fig. 2. Maria Damon. Detail, Wedding shawl, 1998.

5

The first of Damon’s pieces we received (1998) is a large, radiant blue “throw” blanket. As in each piece we have, the palette of colors is wonderfully chosen: here primarily a range of aqua blue and purples, with subtle use of green and brown. It looks like a (soft) reef in a tropical bay, embedded with shimmering silver thread (minnows). If it weren’t a blanket, you might think it is a rug (which would feel really good to walk on since some of the yarn is cashmere). At several points, discernible (ornate, shapely) configurations are seen, such as snowflake-like patterns inside the fringe at the top, fishtail (perhaps wishbone) at the bottom, and diagonal shapes elsewhere in Fig. 2.

6

The rest of the field is back and forth lines, criss-crossing dashes (sometimes belts) in various colors. The other fringed end is grounded in brown, although I wouldn’t say a singular perspective as such is possible to assert. I see the widths of colors as periods of attentive time, unspecified amounts of time, although I know there are other factors that come into play (not the least of which would be the amount of on-hand materials). Do the details and choices of color mean something specific? Do they reflect the ocean and earth, where the brown/green land meets purple aqua ocean: Maine and Cape Cod? Someone who knows our family backgrounds and landscapes well would know this.

Fig. 3. Maria Damon. Detail, Wedding shawl, 1998.

7

Since there are only moments of details, however, fragments suggesting something literal, we can call them postmodern assertions, left for the beholder understand her/himself. The object itself, a wedding gift, projects vibrancy, meaning to me an ontology, which happens to explicitly represent the “thick and thin” of marriage, complete with silver lining, a touch of metallic silver thread (See Fig. 3 for detail). We have purposefully used the blanket in our living rooms.

8

The narrowest (about six inches wide), and probably most used piece, is a “table runner,” although I have also described it as a “stiff scarf” (a purpose for which it could stylishly be used). This piece has spent a lot of time on a fireplace mantle on Staten Island and on a wooden coffee table in our log house in New Jersey.

Fig. 4. Maria Damon. Table runner (2000).

9

As luminous in color as the blanket, it is by appearance a scroll, some kind of textual journey that keeps the eye moving (top to bottom, side to side). Bright light greens contrast with vivid red; small “passages” of purple, blue, as well as (subtly) pink, and yellow form the narrative. A green line runs from end to end (fringe to fringe); a thicker red belt is beside it. Both are punctuated by perpendicular waves (or belts, as above), colors and patterns that are steady and repetitive until they confront, or merge with, a more turbulent, integrated pattern cumulatively resembling static, or, better, a television screen that needs its vertical hold adjusted.

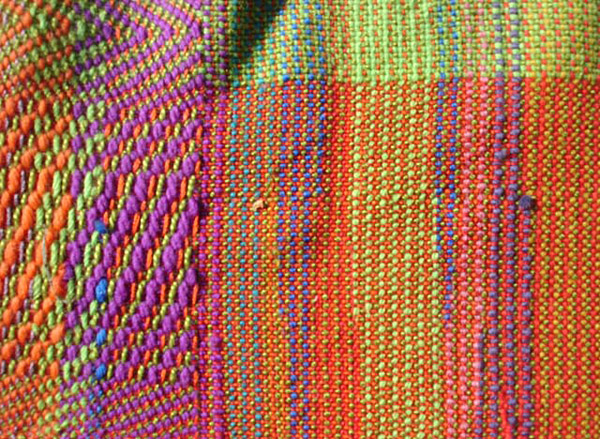

Fig. 5. Maria Damon. Detail, Table runner (2000).

10

This characteristic emerges at several points, most dramatically in the middle of the piece, where the colors and configuration are nearly psychedelic (Fig. 6).[1] The overall smoothness of the visual path is subject to periodic disruption, which seems analogous to what happens, even in the best of cases, within the domestic sphere.

Fig. 6. Maria Damon. Detail, Table runner (2000).

11

The most subdued piece, which Damon sent after our first daughter was born (Constellation, 1999), is a baby blanket (at 21 x 25.5 inches it is just large enough to cover a newborn). Predominantly salmon and white, with peach accents, this example, which according to my wife radiates, “baby girl, baby girl,” is very different from the others. It is, by far, the most consistently patterned of the three.

Fig. 7. Maria Damon. Detail, Baby blanket (1999).

12

The weaving throughout entire body of the blanket, with a single semi-dramatic exception near one end (which is certainly not the first thing someone would notice), is completely uniform.

Fig. 8. Maria Damon. Detail, Baby blanket (1999).

13

One of the esoteric connections I cannot help but make here involves a poem Kamau Brathwaite wrote for Constellation, which Damon is aware of, urging her parents not to confound her. So when I see Damon’s design, near perfection in stitch, I recall the poem. Making a disordered baby blanket is probably not a good idea. Yet nothing (or no one) is perfect, so for a denser, tighter section of peach to be inserted, which essentially forms a line that interrupts an otherwise flawlessly steady pattern, seems within acceptable boundaries of reason (and intention). One may wish to promote form, but not always to the point of perfection. Something handmade, without any visual deviation from scale or pattern, might in fact seem artificial. Too many of our manufactured objects, landscapes, and designs are too homogenous, in any case, and what we make is what we promote. As an imperfect, but absolutely gorgeous and functional object, it is an ideal offering. I have a fond memory of tucking our second daughter, Aleatory, in for a nap beneath the blanket about five weeks after she was born, just before departing for the BIOS symposium in West Virginia (which Damon also attended).

14

Something interesting occurred while recently doing some photo documentation of these pieces. I happened to randomly placed the table-runner atop the large blanket and was astonished to discover that the length (or width) and stitch patterns on sections of each were identical, as seen at various places in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Maria Damon. Detail, Baby blanket with Table runner overlap.

15

Since the length of patterning completely vary in each piece, it surprised me to see lines of exact same width visually merging when they were layered. I was impressed that the grains (signals) of two very different objects, made at different times, were inimical to one another. Some kind of general stylistic continuity may be in play here, but because I have seen few other non-verbal examples of her quilting, I don’t know if she has a particular technique that is common to multiple works. It’s likely, since I managed to find this through coincidence by haphazardly juxtaposing two pieces, although maybe I should not generalize this way. She contains multitudes! The patterned weavings she has given us show diversity in style, multiplicity, characterized by qualities of disruption (or, perhaps, interruption), in which the patterns suddenly shift — as different surroundings, mindset, materials, and moods are accessed? If so, how humanistic! If the weaver is not using a template, it would seem such flows, personal and spatial tides, would be expressively reflected.

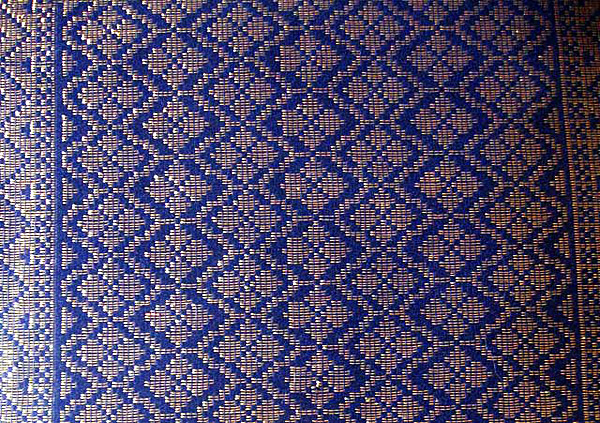

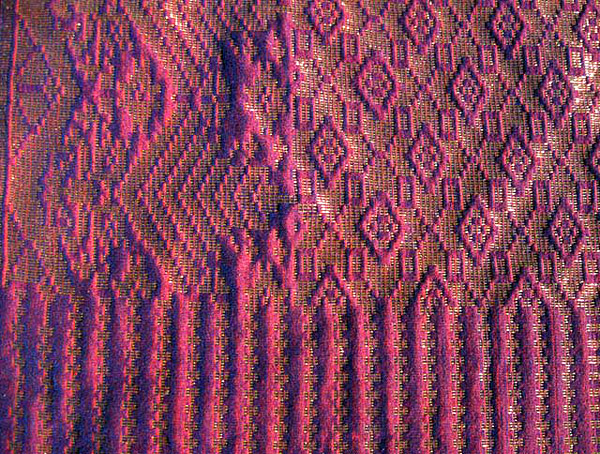

Fig. 10a. Details, Songkit weavings. Malaysia (2001).

Fig. 10b. Details, Songkit weavings. Malaysia (2001).

16

Southeast Asian Songkit weavings are the only other textile we have a small collection of in the house, which are utterly orderly. Like woven and embroidered Mayan trajes (one of which hangs on our living room wall), the songkit weavings are made with looms, often using templates, which have in many regions become mechanized (i.e., what was once done by backstrap loom, or by hand, is now done by machine), which does not diminish their value, but certainly explains the precision.

Fig. 11. Detail, Mayan trajes. Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala (1988).

17

While the cultural codes and symbolic representation embedded in such work are ornately transmitted, they are often relatively easy to read. Damon’s work is, in terms of interpretation, and use of new, spontaneous codes, is much more complex. I am uncertain of how much Damon is working within, or against the tradition of weaving, so often known as “women’s work;” she is perhaps doing both. I do not know how much the average weaver works to “spin a yarn” in her/his work, or even how much Damon has this dimension in mind. But for me (as user/viewer) both senses apply. The weaving is a sublimation of expression, with use value. Oblique stories are told. Like the structure of lines in a book, colors punctuate, vary the appearance of field, and form visual adjectives and verbs.

18

What I see, especially in the first (“blue”) and (“green”) pieces, is a reflection of our asymmetrical, imbalanced culture, and all of its inconsistent values and actions. Considering the overall abstract visual effect, it is possible to find cohesive unity within it. Explicit messages are absent, but in the alternations, something can be read. In the “pink” piece, the baby blanket, which is the most traditional, nearly antiquated, the patterning is almost perfectly consistent. The other two pieces vary wildly in terms of consistency. Fluctuations consist of sections that are steady and routine — reflected by unbroken designs and consistent weights of thread — alongside those that shift abruptly or introduce new colors. These disruptions create a visual punctuation in the tapestry. On one hand, I am inclined to presume, given the heterogeneous appearance, that editorial decisions are made in the moment, and sensorial conditions influence what is happening in the artist’s hands. I see this as a type of making that derives from what is present, or what presents itself. On the other, I realize that the construction must be highly calculated in certain ways, especially with regard to the mathematics of the woven structure. In any case, with our blue blanket and table runner, the overall design, after its structure had been established, may have discovered itself as it went along; in the blanket, the silver thread (lining) is the unifying, steady element. Who knows how premeditated these pieces are? It goes without saying there’s a back and forth to all of them, with arbitrary (maybe non-existent) starting points. [2]

19

Unlike most textiles that are bought and sold in stores, perfectly woven blankets or decorated garments, it’s the interference of patterning in Damon’s works that makes them so important. They are precious but not exactly delicate. They are built-to-last (well made) but not exactly rugged. We adore these offerings of friendship, having them, even if they are not always been out for use or display (preserving them for when our children are past the age of rampant food and beverage spills). My sense is that Damon, as a professor, critic, and poet with diverse interests (cultural studies, literature, and hypertext to name three), uses weaving and yarn as a type of “escape,” making some of her most complex, yet simple, sentences here. She does so not to avoid writing about the culture, but to occupy her focus and hours in ways that do not involve institutions, scholarship, talk, and formal use of language. She creates in an alternative form, passing time meaningfully, contemplatively, with splendorous results. For some, practicing such experimental design is life itself.

Fig. 12, detail, baby blanket (gift from employer), 2005

Whimsical

for Maria Damon

Weaves.

Undulating, undulating

weaves. Undulating, undulating

for

non-

undulating

undulating a

line (diagional)

not a

shaft, undulating

cotton

undulating

page.

Tartan color weave

combination undulating

warp,

closer

fibres of

you

deliberately

play with the slope

achieving

Being

undulating

completed

responses

finished

dust bunnies under my loom:

time’s fun so

put on scarves in undulating colours

not truly represented on scarlet

rivers.

Design undulating

rivers,

fashion

inspired

ancient

combining

harness

somewhat set up at home,

harness

undulating

lolly troubleshooting

border

interior portion

full

ZERO

forever:

undulating

close-up,

purse

and on to make.

[1] “The pattern,” writes Damon, “is called ‘undulating twill,’ a blend of the psychedelically unstable and the most basic and stable of all weaves” (Email 2009).

[2] Damon describes the requirements and compositional possibilities of the process in a follow-up email: “I have to set up the pattern before I start the actual weaving, but even within the pattern of the warp [the yarn running the length of the piece] it is possible to achieve a great deal of variation in the weft [the yarn running the width of the piece, which is composed on the static warp” (2009).

Maria Damon; photo by Aldon Nielsen

Maria Damon teaches poetry and poetics at the University of Minnesota. She is the author of The Dark End of the Street: Margins in American Vanguard Poetry; co-author (with mIEKAL aND) of book-length poems Literature Nation, eros/ion, and pleasureTEXTpossession; and co-editor, with Ira Livingston, of Poetry and Cultural Studies: A Reader.

Christopher Funkhouser; photo by George Paccielo

Poet, scholar, and multimedia artist Christopher Funkhouser teaches in the Humanities Department at New Jersey Institute of Technology. A leading researcher in the developing genre of digital poetry, he was a Visiting Fulbright Scholar at Multimedia University in Cyberjaya, Malaysia, in 2006; in 2007 he was on the faculty of the summer writing program at Naropa University. Most recently, the Associated Press commissioned him to prepare digital poems for the occasion of Barack Obama’s inauguration. He is author of a major documentary study, Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995, published in the Modern and Contemporary Poetics Series at University of Alabama Press (2007). Since 1986 he has been an editor with We Press (http://www.wepress.org), with whom he has produced poetry in a variety of media. For more info see: http://web.njit.edu/~funkhous