| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/r-sheppard-rb-thorpe.shtml

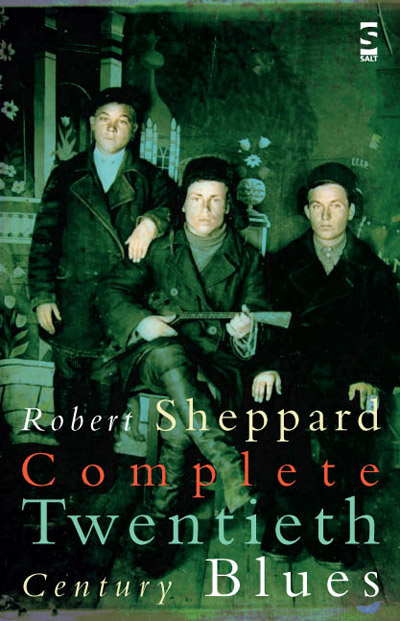

Robert Sheppard

Complete Twentieth Century Blues

reviewed by Todd Nathan Thorpe

Salt Publishing, isbn 9781844712649

This review is about 8 printed pages long. It is copyright © Todd Nathan Thorpe and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

1

Salt’s publication of Robert Sheppard’s Complete Twentieth Century Blues brings a dispersed body of work together in a single volume where the poetry’s full range and ambition become all the more evident. The book’s title is fashioned from the titles of a song of Noël Coward’s, a poem of Kenneth Fearing’s, and an artwork by Joseph Beuys, which gives a good idea of the range of reference to be found in CTCB. Neither a long poem nor a congeries of singular poems, the book is a montage of scenes taken from the endless recycling of media across ever proliferating screens, ever more crowded airwaves, and ever more heavily trafficked bandwidth. From 3 Codes and Diodes are both Odes, dedicated to Bob Cobbing,

Paragraph 2

Overlay of systems,

enough revealed delight to design

us all, while

magnetic words twin the

reader swiftly across echo’s edge.

3

CTCB is a book that queries the condition of being a book, where being a book means being a historical repository, a vehicle for personal expression, or a linear textual sequence. “We’re no longer in the Era of Metanarratives it seems; are we in the Meganarrative itself,” Sheppard asks. Approaching an answer to that question, there are multiple pathways through the text, and the poems are numbered as well as titled. The end of the book is an Index of Strands through and out of Twentieth Century Blues in which poems are listed by number and the strands have such names as Abjective Stutter or Histories of Sensation. Sheppard calls his book “a network, but not a work”: it is an open structure designed “To provoke. To excite,” where excitement is not consumerist thrill, but a heightened, energetic state of mind. The book has a use-value, if not precisely a goal.

4

The book is composed of language that might be overheard in public places, saturated with private despairs and desires, worked into a tense, productive relation to form through Sheppard’s explorations of the poetic line. The boundary between public language and private selves is continually transgressed in CTCB. In an aleatory vernacular to which parataxis and syntactic rupture are central, the poetry’s language moves across the fields of politics, history, economics, and popular culture, poaching from a ubiquitous urban banality a mordant diction that betrays lives fueled by sex, anger, hopelessness, and avarice that for all their constriction nevertheless open up, on rare and beautiful occasions, to something altogether else, another human being. Without sentiment, occasionally contact is made. From 32 For Scott Thurston,

5

unspoken a tongue on a downy lobe

steaming the sentient lock with its breath

and she turns to you implores you

be fleshed for her kiss or

stands silent in shadow othered in stone

as a million suns scorch their mottos

6

The poem’s real tenderness is amplified by the anomie the book everywhere evidences. The general anomic condition does not abate, nor do the poems ever step outside of a history that seems less and less to have ended. The book offers no utopian prescriptions, “Utopia deleted Utopia,” Sheppard writes in 5 Coda. In any case, contact is more punctual than permanent, more aspirational than actual, but perhaps that is corollary to its ethical difficulty in the world Sheppard illuminates.

7

the recognition that

another human being has responded

haunts

with its hope that the street might prove ‘the last vestige of democratic exchange’

8

A specter haunting CTCB is democracy’s. CTCB sounds at times like a soundtrack to disaster capitalism, tolling the take the industrialists of culture grab from their unremitting assault on sense and the senses.

9

The previous excerpt was taken from 63 The End of the Twentieth Century: a Text for Readers and Writers. It is one of the many poems in which Sheppard reflects on the ambitions of his work and on its literary, philosophical, and cultural sources. Another key entry in this regard is 18 (incorporating 14) Poetic Sequencing and the New, where Sheppard writes, “the future belongs to the unknown relation of a not yet unfolded world and the, at present, slenderly formed practices of those who will work in it, and against it. You cannot see into the granite hearts of Beuys’ sculpture. But it might be possible to provide structures that can transform in terms of poetics and poetic focus as the world transforms itself.” If the oppressive conditions of the present are to be negated, then those fragile and inchoate forms of life that are not yet fully imaginable must be given room to grow. Sheppard’s poetry works to effect this germinal opening.

10

Finding “the poetics of no in the poetics of yes,” Sheppard’s poetry is an aesthetic challenge to a degraded political environment in the sense that Jacques Ranciére means when he calls aesthetics a “distribution of the sensible.” Ranciére writes, “aesthetics can be understood as ... the system of a priori forms determining what presents itself to sense experience. [Aesthetics] determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience” (13). Forms of space and time are historical, not given apodictically, and they need not to be taken for granted. Reorganize experience aesthetically and reconcieve politics.

11

In The Materialisation of Soap 1947, Sheppard writes, “the monochrome world flickers/ At the emotive edge of our fake memories.” Bodies are haunted by screen memories through CTCB; late capital’s psychic dislocation of the subject is palpable. Media saturation has produced a world that is like a bad newsreel of itself populated with prefabricated characters. In such a Matrix-like world, nostalgia can only be a species of bad faith or an ideologically motivated bad pastoral.

12

Sheppard’s poetic negation is also akin to Theodor Adorno’s “reflections from damaged life.” In Minima Moralia’s opening dedication to Max Horkheimer, Adorno writes, “He who wishes to know the truth about life in its immediacy must scrutinize its estranged form, the objective powers that determine individual existence even in its most hidden recesses.” Throughout the book, Sheppard fashions a critical poetics of late capitalist bio-power in which the structuring of the subject by the discourses of the market become, ironically, the conditions of possibility for poetry. From 2 Empty Diary 1954,

13

We are statues of ourselves, stiffened eulogies

in the arthritic history of imperial endeavour

(the world of his syllabics: the words

we silently mouth: our faces networks of

electric lies: our lips would seal: our

eyes close on a world which will

drill its electrodes into our mermaid flesh

sketched in by the boss) Say it:

14

If CTCB is an act of constructive, aesthetic negation, it nevertheless makes no promises. The poems are no prophylactic against the relentless policing of the public nor does the poetry place much faith in purifying the language of the tribe. Modernity is its own nightmare, as true now as it was for Baudelaire. In Internal Exile 3 Sheppard asks the question of modernity’s negation without imagining its supercession,

15

Is this a model

Of the world that does not exist, straining

For a new referent?

16

As Sheppard has it, “the politics of this, though, becomes less utopian, less the text opening horizons of possibility, Marcuse’s Aesthetic Dimension glittering with its pre-figurations. It becomes more strategic: a denial of what we presently are.” I wonder about this gesture. Can such ambitious poetry simply walk away from totality with by appealing to futurity, a futurity achieved by the reader’s collaboration in semiotic disruption? Sheppard might answer that his work is an immanent critique, processual and not teleological, more given to ventilating a stale atmosphere than providing a new social design.

17

CTCB looks to pleasure as a fulcrum by which it might move, if not the world, then at least the reader’s perception of what it means to be human. From 31 Basalt Wind-chimes for the Window-Box of Earthly Pleasures,

18

Not a book of ayres not a solid monotone. An eye. An ear. Willed to pleasure, let’s take a note for a walk across the humming strings. Human

19

Throughout CTCB desire oils late capitalism’s gears but is all too frequently only the barest simulacrum of love, another specter that haunts CTCB.

20

Polyphonic ejaculation! Do you

want to handle my swollen gland; in

my language we have the same word

for ‘man’ and ‘girl’, for ‘love

‘dream

21

Sheppard’s poetry shows sexuality in many guises, none of them sentimental. Sex, though frequently a caricature of itself, circulates throughout CTCB as a wish for contact. Sex figures as poetry’s other throughout CTCB, which means, perhaps, that my problem with the poetry’s relation to totality needs to be rethought in terms of a more fundamental experiential openness. How do words such as love and dream work to constellate a future that can only be augured at present? Can one move beyond the poem’s crude sexual positivism to something else? Can desire break out of its corporate channels? Such open questions find their corollary form in the poetry’s open structure.

22

The poetry’s embrace of a shifting sense of form allows it find the pressure a phrase or image can bring to bear on a limning of our media saturated era. The poetry is not precious, studied, or mannered, nor is it in pursuit of that least of all virtues, novelty, which is as exciting as the words ‘new and improved’ on a box of detergent. CTCB is poetry with an authentic ear, which is not the same as, is in fact opposed to, poetry with an ear for authenticity. CTCB sounds throughout the theme that we have all been spoken before, that our well-formed selves are surreptitious bargains with mongrel, mongered media. From 19 Empty Diary 1990, 1,

23

Her lips, pursed,

mouth a public language to parade in.

24

In 46 Armchair Adoption, Sheppard’s distrust of the well-formed subject is equally in evidence:

25

Cough up a certain one

lineness. Download

the Person as Absolute Theme

You do it. nessness.”

26

The struggling subjects encountered in CTCB are almost always part of a city, a word that recurs frequently in the book. The city is a contradictory space that is on the verge of being dematerialized by technologies of communication, reduced to what the 1960s urbanist Melvin Webber called the “non-place urban realm,” while at the same moment it harbors human life in its implacable materiality. In this city, what matters is the continual circulation of goods and people, but such modern restlessness is driven by “perpetual forgetting: perpetual longing.”

27

The Marcuse-inspired ambition of the book “to educate desire,” “to repurpose kitsch” becomes the rationale for what Sheppard calls “a force to vent: Velopoesis.” The root ‘velox’ meaning swift yields a poetry that embraces the rapid shifts of urban life: “a chamber of twentieth century echoes rings. Soiled prose-songs of Velopolis.” Substituting ‘polis’ for ‘city’, which also foregrounds the connection between poetry/poesis and polis, Sheppard’s poetry continually conjures the modern, if not modernist, image of the city, a place of alienation and promiscuity, of the random encounter and endless traffic. By arresting the endless circulation of capital, Sheppard’s work seeks to puncture capital’s self-policing barriers, barriers in which contemporary language is always already caught.

28

I find resonances in Sheppard’s poetry not only with the work of Kenneth Fearing, but also the urban poets of the Chicago Renaissance such as Carl Sandburg or Sherwood Anderson who traced similar circuits of dislocation at urban industrial modernity’s outset. Sheppard’s urbanism also places his work in conversation with some of the most interesting poetry being written on this side of the Atlantic by such American poets as Robert Fitterman, Brenda Coultas, Joshua Clover, or Ed Roberson, as each of these poets writes poems that explore the intersection of language and the urban fabric. In CTCB and elsewhere, Sheppard acknowledges the impact of Barrett Watten’s poetry on his own.

29

CTCB belongs to a special cadre, if not genre, of British poetry that investigates the urban faultlines of culture. CTCB and Allen Fisher’s Place are two large books that could be compared with advantage to both. In Far Language, a book of Sheppard’s critical prose published in 1999, he dwells at some length on Fisher’s organizational plan in comparison to the then fledgling CTCB. Bill Griffiths’s Book of Spilt Cities — “the city is in a state of trauma” — is another volume of acerbic urban verse that would find strong resonances with CTCB, though Griffiths’s work is focused closely on Thatcherism’s impact on London specifically. Edwards’s Nostalgia for Unknown Cities is also among works with which CTCB could profitably be compared even though it is a prose work. Edwards’s beautiful, slim volume is virtually a prose poem describing the unraveling of the urban fabric: “they read the story of how the city had been burned to the ground even before it was born, and of its rise to power within 50 years, and its subsequent industrial decline in the last half of the 20th century. They agreed they would never forget this.” British poets have been among the most articulate explorers of urban modernity and though the subject of British poetry and the city has generated a vital and growing critical literature there is a great deal of work yet to do on the connection between urban and poetic form.

30

Sheppard writes “at the edge of England, this liminal city/ in a room in a house as combustible as a Kosovan dwelling.” How will this world unfold? Will economic and social inequities cause it to explode, shredding the urban fabric? Sheppard lives and works in Liverpool, a city that still shows traces of the damage caused by bombing during the Second World War. Liverpool, a port that profited immensely from the slave trade and was a primary point of departure for Irish immigrants leaving for America throughout the nineteenth century. In 2008, it is the European Capital of Culture, but this new, improved version of culture is the neoliberal veneer of the globalization that is as much an engine of displacement and dislocation as it is economic growth. If Sheppard’s tone is sometimes overly apocalyptic, nonetheless the prospects for our now majority urban planet are daunting.

31

Unlike the destruction of the Second World War from which ardent futurists eagerly sifted the remnants of modernity from the results of collective barbarity, today disaster capitalism is content to leave whole regions to return to their pre-Fordist states. Perhaps we have never been modern, and all the rotting factories and empty villages that dot the British and American landscapes like so many mushrooms are simply the flora of a social ecology that never really left The Jungle. All the cultural institutions in the world, with their programmatic recuperation of the liberal democratic benefits of modernity, can’t replace the social equity of the post-World War II era that now seems more like an aberration than a promise. Global cities provide the spectacle, the media the 24/7 running commentary, and the consumer of images drifts in the post-productive splendor of the interim between the American century and the return of the East. History is an urban theme park. Robert Sheppard’s Complete Twentieth Century Blues knows this carnival almost all too well.

Adorno, Theodor. Minima Moralia. Trans. F. N. Jephcott. London: Verso, 2005.

Ranciére, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Trans. Gabriel Rockhill. London; New York: Continuum, 2004.

Robert Sheppard

Robert Sheppard was born in 1955 and educated at the University of East Anglia. Between 1989 and 2000 he worked on the network of texts called Twentieth Century Blues. Previous excerpts from the project include Empty Diaries (1998) and The Lores (2003). A recent volume is Hymns to the God in which my Typewriter Believes (2006), and a sonnet sequence, Warrant Error, is due for publication by Shearsman in 2009. His work is anthologised in Other and the Oxford Anthology of British and Irish Poetry, in which he is described as ‘at the forefront of (the) movement sometimes called linguistically innovative poetry’. He is Professor of Poetry and Poetics at Edge Hill University in Lancashire in the UK, and has also published criticism and poetics, including The Poetry of Saying (2005) and Iain Sinclair (2007). He edits Pages as a blogzine and lives in Liverpool.

Todd Nathan Thorpe

Todd Nathan Thorpe attends the University of Notre Dame where he is working on a dissertation, Poetry, Modernity, and Urbanization from Twentieth-Century Chicago to Twenty-First-Century London, combining his interests in poetry, urban theory, and ecocriticism. He’s published an interview with Peter Riley in Jacket Magazine, and has a review of Roberto Tejada’s Mirrors for Gold forthcoming in Latino Poetry Review.