| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 4 printed pages long. It is copyright © Kathleen Fraser and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/oppen-k-fraser.shtml

Back to the George Oppen feature Contents list

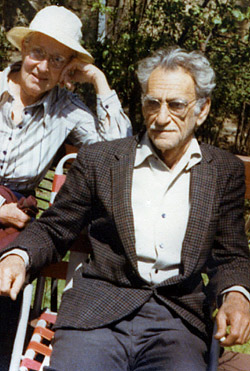

Mary Oppen, George Oppen, Swathmore, 1979. Photo Robert S. DuPlessis

“Salute to George Oppen”

for The Poetry Center at the SF Public Library

1

My first encounter with George Oppen was on a snowy January night in 1967 when he’d taken the subway, with his wife Mary, from their Brooklyn flat to St. Mark’s Church in NYC’s East Village to read at The Poetry Project. He’d come to read from This in Which, published a year or so earlier by New Directions. His audience was made up mostly of first and second generation writers and artists associated with the Black Mountain poetry community but even more particularly from those beginning to take nourishment from a related but discreetly different group of “Objectivist” poets, not yet widely known.

Paragraph 2

Along with a few of my peers, I’d been reading Oppen, Reznikoff and Zukofsky with almost scientific curiosity, but had come to Oppen’s reading completely unprepared for the mournful severity that inhabited his voice that night. He wasted no syllable, his lines held the air firmly around each phrase as if scored for silence as much as speech — this structure intentionally directed to a deep and private meditation that, nevertheless, had its political agenda. From his first poem, I was riveted; we were poets infected by the city’s speed and daily fracture, often driven towards the relief of invention for its own sake or the light-hearted amusement of performative play to keep us on the path of resistance. Everything was up for grabs in the field of mainstream tedium and re-play.

3

On that night, Oppen placed in us a gravity we’d been craving without knowing it. We’d been trying to find a way to live and do our work during the stressful years of the Vietnam war that ate away at us. Oppen turned our minds with the force of a magnet towards the difficult unavoidable evidence of the human condition — in particular, the terrible uses of America’s wealth and power enacted during our own overlapping lifetimes of war. Oppen did not whine, lament nor preach. He reminded us, rather, of human touch and our capacity to re-imagine “the small nouns/ crying faith” (“Psalm”).

4

He wrote and spoke with a shy eloquence that turned us away from posturing, giving us back the unnegotiable beat of the human claim we’d lost touch with, competing as it did with the unremitting dailiness of living in American cities, away from our clearest instincts.

5

Later that same night, when some of us went out for a beer with George and Mary, one could feel how energized they were to be with younger poets engaged in taking on the status quo. Mary was sitting next to me at the bar and she told me that she and George had made the big decision to leave the East Coast and move to San Francisco where George’s sister lived and where they anticipated the chance for a less harsh and threatened kind of life as they grew older. Mary liked to fish, and could do it from the pier at the end of Polk St. They needed the sea close enough to smell it. They would leave for the West Coast that spring.

6

I, too, had determined that the time had come to leave “the city” — in part because of the difficulty of raising a new born son in a degraded neighborhood overrun by drug-related crime. I told Mary that I hoped to initiate a move to San Francisco the following autumn. When we parted later that evening, she and George asked me — with a gesture of complete spontaneity — to keep in touch and to come see them once we’d settled. Ten months later, I called them from San Francisco and our familial friendship began in earnest.

7

There were many visits. One Saturday morning I arrived at around 11 with a coffee cake for our brunch and the two of them greeted me in the most marvelous dressing gowns, donned with amusement and pleasure: Mary’s a full-length sweep of bottle green velvet, George’s somewhere between a smoking jacket and a silk-sashed bathrobe with a little tuft of grey chest hair showing at the throat — definitely a great model for a sexy couple in their seventies.

8

During our three-way discussions, we would often talk about poetry and George’s frustrations with much of the new work being produced by his younger colleagues that neither suited his politics nor his linguistic severity. I had to hold my tongue more than once when he made one of his over-the-top generalizations about women poets: “Women poets don’t talk to God... that’s their trouble.” Or, “Why do women poets write only about broken love affairs, instead of taking on the important questions of existence?” Mary and I just rolled our eyes. His old-world persuasions came as a surprise each time they appeared, in part because he was such a tender and affectionate person. But in an odd way, the rigidity of his gender bias helped me to think my way into a more articulate position in later exchanges.

9

I eventually decided not to send George my poems, at least not until their imperfect drafts had been rescued into publication. I needed, at that point, to be available to the changing ground of my own process before becoming too porous to others’ authority. I adored this man but I didn’t want his critical certainties to install themselves too unconditionally in my brain. In person, however, more range was in play. One could introduce at-odds perspectives with feisty banter, for his merriness was easily persuaded to enter the conversation. A letter, on the other hand, was frozen in time; it made one accountable for impulsive and changing views still finding their way.

10

One evening, in the early seventies, George and Mary came for supper with Mark Linenthal and Frances Jaffer, both of whom were intensely engaged by then with Oppen’s poetry. It was a fairly rollicking evening of good food and wine with serious views flying around the table and it may have been that night when Frances admitted to George — after he’d complained about “women poets not reading enough philosophy” — that she really did not like philosophy, could not stand all those systems. His reply was simply stated: “I don’t read philosophy for the systems. I read for the language.”

11

It was soon after this exchange that Frances took up the pre-Socratics, feeling more comfortable with their fragmented texts and “lost systems.” She was particularly excited by Heraclitus and Parmenides. She later characterized the first poem in her later collection, ALTERNATE Endings as “a feminist conversation with George’s poem ‘If all the world went up.”

12

And so the dynamic developed among us, with poetics, politics and gender positions becoming more fluid as they were actively engaged. Mary Oppen, who had shown the most reserve in our conversations, began working on Meaning a Life, published some four years later in 1978 by Black Sparrow. It was through that account of the Oppen’s long companionship that we first got wind of the poetry of Lorine Niedecker and of her fissured relation to Louis Zukofsky. It was also during the prelude to writing her book that Mary asked if I’d ever read Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage — the brilliant twelve- volume modernist work never mentioned on any reading list during my university major in English literature. An unexpected exchange of information was occurring in our group that both opened our eyes and strengthened our mutual bonds as friends and writers.

13

However, it has been through reading Oppen’s poetry that I’ve most learned how each act of attention sustains one’s writing life and the making of work: how the essential ground of silence frames each phrase; in what sense the space of the page may illuminate an infinite shifting of syntax or measure; and how many ways the line speaks to us, wakes us up and teaches us how to read the exactness of difficulty.

— Kathleen Fraser

April 22. 2008