| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long. It is copyright © Michael Heller and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/oppen-heller.shtml

Back to the George Oppen feature Contents list

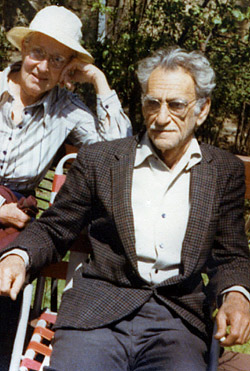

Mary Oppen, George Oppen, Swathmore, 1979. Photo Robert S. DuPlessis

(a talk given at the Kelly Writers House celebration of George Oppen, April 7, 2008)

paragraph 1

An assay — the thing I’m doing here rather than an essay — an assay: an analytic procedure to test the properties and/or composition of a particular substance. Recall that Rexroth titled a volume of his critical writings “Assays.”

2

After much thinking and many hours writing hundreds of pages on George Oppen’s work, I am still trying to know what kind of poet he is, what is the nature of his poetry. The labels: modernist, objectivist, classicist, etc. They tell me almost nothing.

3

Influenced by Heidegger. Perhaps more important, he seems to participate — in the Heideggerian sense — as a foundational poet (the term Heidegger used to describe Hölderlin). The foundational poet alters not only poetry’s paths and modes of creation but alters or suggests a new way of looking at the basic themes of poetry: love, desire, language, history, memory, the socio-political and cultural worlds we inhabit. He is extra-literary.

4

The parallels between Hölderlin and Oppen are numerous — the odd disjunctive look and feel of their late works, both written in the shadow of mental disease. Both also worked in what Heidegger characterized as a “destitute time.” And both careers — Hölderlin’s investment and then rejection of German Idealism; Oppen’s of Marxism and the Party — follow Heiddeger’s thought that “it is a necessary part of the poet’s nature that, before he can be truly a poet in such an age, the time’s destitution must have made the whole being and vocation of the poet a poetic question for him” (Heidegger in Poetry, Language, Thought p. 94).

5

I take up Oppen’s thematics of love and desire, not thinking of romantic or sentimental effusions, but as a quality that sustains and allows the poet to be sustained in a destitute time.

6

So the first assay is to try finding out what the substance of love is in Oppen’s work.

7

I start with the poem “Solution” (45) because the substance that I am looking for is, by Oppen’s design, the poem’s subject as an absence. This absence as I read the poem is what makes the poem work. “Solution” begins with these lines:

8

The puzzle assembled

At last in the box lid...

9

The line break with its deeply psychological “At last” sounds like a metaphysicial sigh of relief. As though now syntax could go on all by itself, a little machine manufacturing the rest of the poem, enumerating its building blocks, the puzzle pieces: the “green hillside,” “a house,” “a barn,” “a man,” “and wife,” (what else to have in a ‘solution’ but a ‘wife’ rather than a ‘woman’). The word “wife,” as it stands in apposition to the more generic “man,” operates like a number of other words in the poem, (such as that “at last” above, also “lucid,” “crazes” and “sordid”). Such words are not simply pictorial, descriptive or informational. They have a rhetorical or vectorial edge that directs the poem, illuminating powerful tensions that undercut the stability of a “solution.” It is these words that undermine the subject of the poem and make the “at last” seem prematurely self-satisfied. In fact, the metaphysical relief of that first line break/sigh becomes powerfully ironic. It is both temporary and false.

10

Once “assembled,” the completed puzzle is fakery, its “jigsaw of cracks/crazes the landscape.” “Nowhere” — the thing being solved — can one sense the sordid cellars, the foundations of the puzzle’s pictured world. (Such cellars might contain anything from old junk to the family’s dead bodies, to the skeletons of dead Native-Americans who lived on the spot before the house or barn were built). The puzzle both expresses and hides the cost, in terms of psychic health, world politics, markets, ethical well-being, of our “lucid,” “polychrome” living arrangements (lifestyles? Oppen would hate the word). In fact, the assembled puzzle could be Oppen’s Dante-esque picture of the frozen, solidified lowest depths of Hell, its stasis, its moral and psychic entropy, its stifling absence of risk or imagination. []

11

Is there a backstory? Is the poem Oppen’s critique of his own experience of being guided/ seduced by a rationalistic, all-encompassing “solution,” American Communist Party Marxism?

12

Fifteen years after he published the poem, Oppen in a letter to Frances Jaffer (a San Francisco poet and a founder and editor of How/ ever, a magazine that focused on feminist issues in poetry and poetics), said that the poem “Solution,” “describes the refusal,” as he puts it, “to think outside a field, a set of rules, of definitions... whereupon ‘it’ becomes a complete puzzle” (SL 281). The entire letter to Jaffer shows Oppen himself caught in more than a little within-the-box thinking with respect to women.

13

I’m concerned with how the dynamics of this theme are amplified in “Time of the Missile” (70). Here boundaries and adjacencies, “the realm of nations,” endanger “viviporous” space, the space that gives birth to new life. Poetry in Oppen is here a transubstantiated vision, a sheltering modality with respect to the “other” — to the largest of othernesses, the “Place of the mind/And eye,” that can win back the life-producing space of creativity from the death-producing peril created by our own minds. Oppen’s poem veers close to solipsism, and yet, as we see quite often in Oppen’s notes and letters, the cause and effect he focuses most attentively on are those of the mind making and unmaking worlds.

14

“Man,” Hölderlin notes, “is a conversation,” a thought that possibly came to Oppen via Heidegger. We can titrate Oppen’s work for its many congeries of such thoughts — (see Peter Nicholls’s recent George Oppen and the Fate of Modernism). The backdrop to this poem and many others of Oppen’s is that, as Heidegger writes, “poetry is the inaugural naming of being...poetry never takes language as a raw material ready to hand, rather it is poetry which first makes language possible,” i.e. “gives life-producing effects in a destitute time.” So when Oppen insists in “Leviathan” (89), “We must talk now,” i.e. we must be in conversation, “talk” is already embraced and enfolded into poetry. The title, with its hints of Hobbes and Jonah in the whale (viviparously?), stresses that our “talk” occurs amidst the precariousness of the human situation. “Fear/Is fear.” Oppen writes, “But we abandon one another.” Without the “talk,” without poetry, we have no way to place ourselves outside of that fear, to open to love, my initial theme.

15

Oppen’s poems express the space and articulation of poetry as a kind of surrounding love, as in “O Western Wind,” (74) where the woman (his wife Mary, we suppose), moves in “a world around her like a shadow,” where “something is being made — /Prepared/Clear in front of her as open air?” The poem is made in the very place that love makes clear. The poet can “write again” where the face of the beloved, her “Beautiful and wide / blue eyes / Across all my vision” signals that for an instant the loved world and the poem’s world are a simultaneity. Such a simultaneity is replicated in “The Forms of Love,” (106) where the lovers grope their way in “the bright / incredible light” wondering if they are stepping into lake or fog. Like Oppen’s idea of the poem as disclosure, this is also love as disclosure, not possession, but discovery.

16

As we know from “Of This All Things...,” Oppen’s feeling is that love is neither privacy nor shelter but the companionate search for “visions.” But there is also a subtext or grounding in an ethics of tact, of apartness and solitude as the fundamental human condition. “We will not breach the world/ these small worlds least / of all,” he says in “Penobscot.” The sentiment gets rewritten from another side in “Ballad” with its “What I like more than anything / Is to visit other islands.” This ethical awareness works against hubris, cultural pride and universalized utopian ideas. The arena in which love or desire are worked out, then, involves a kind of alertness that transforms the usual ironic distance of poetry into an embracing spaciousness in which thing and fact can stand by themselves.

17

And while the beginnings of this outlook are contained in the poems I’ve mentioned above, the later poems are suffused with it. Take for instance “A Morality Play: Preface” in Seascape: Needle’s Eye, (221,2) where the “feminine light // feminine ardor” define love in terms of otherness and distance, defining it too against a kind of fear-love in the mass movements described in the poem where togetherness is bonded not by visions but comforts. “Huddled among each other” is an almost craven picture of an emotion that mirrors the closed up spaces of “Solution,” the poem I began with above. In a way, the entire San Francisco series is an investigation of the authentic and inauthentic bases of community.

18

Thus Oppen’s thematics of love is also offset and entangled in a thematics of poetic truth, as in “The Little Pin: Fragment” (254) where Oppen enjoins the two against “dishonest music” to make it possible that the imagination: “world / sometimes be / world...” also be love, “o western wind to speak of this.”

___________________

Note: page numbers refer to New Collected Poems by George Oppen, New Directions Publishers, 2002.

Michael Heller

Michael Heller is a poet, essayist and critic. His most recent critical book is Speaking the Estranged: Essays on the Work of George Oppen (Salt, 2008). Forthcoming in 2009 are a new book of poetry, Eschaton (Talisman), and Two Novellas (ahadada books).