| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 12 printed pages long. It is copyright © Pat Clifford and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/oppen-clifford-bose.shtml

Back to the George Oppen feature Contents list

Paragraph 1

The following paper was presented as part of George Oppen: A Centenary Conversation at SUNY Buffalo on April 24–25, 2008. This paper engages the work of George Oppen and Buddhadev Bose, archived correspondence, as well as interviews with Damayanti Basu Singh and Jyotirmoy Datta. Special thanks to Aryanil Mukherjee for his expertise, encouragement and translation assistance.

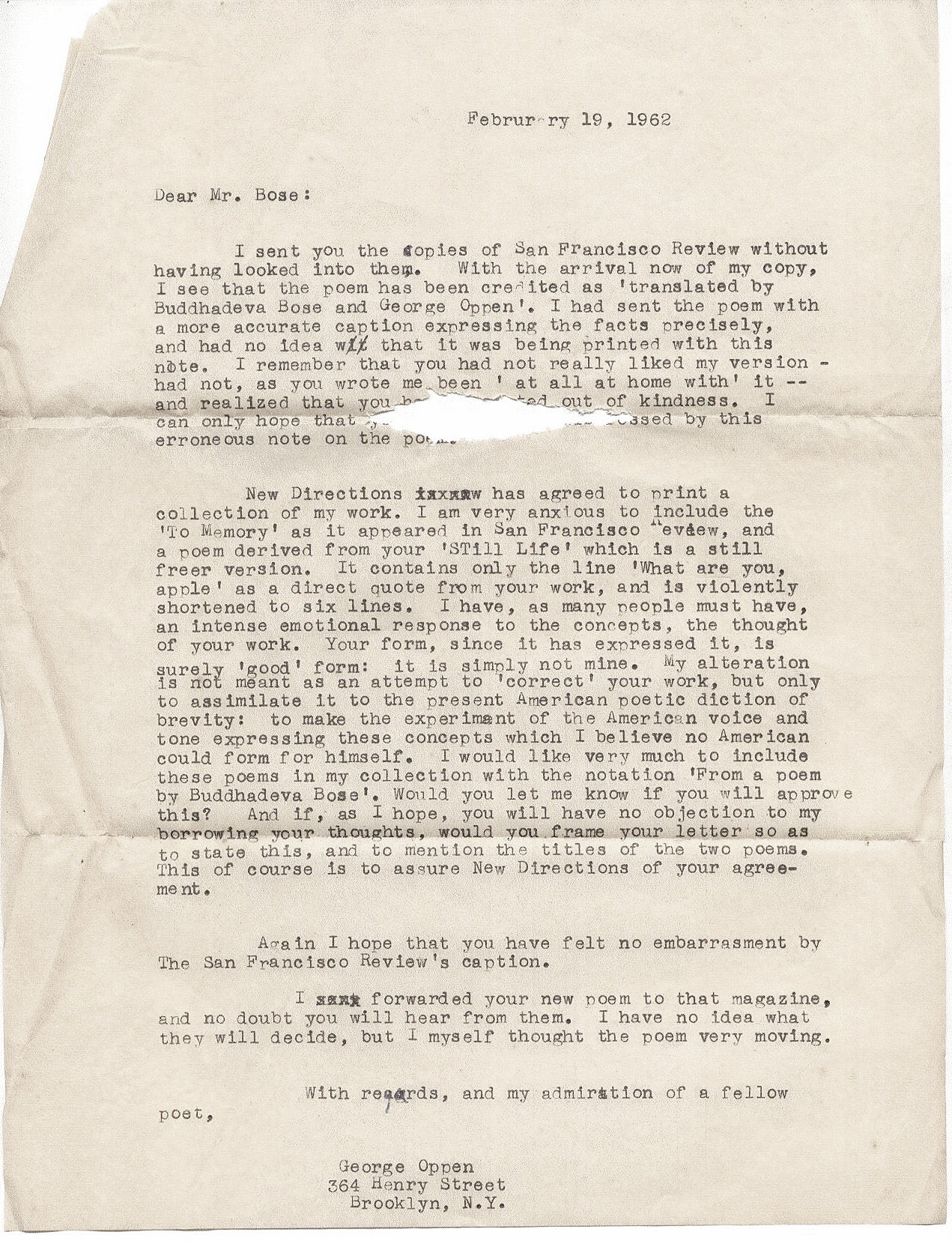

A letter from George Oppen to Buddhadev Bose (February 1962) has recently come to light (April 2009), and is reproduced and discussed below.

2

The period from 1961 to 1964 not only marked George Oppen’s return to publishing, but also a correspondence and friendship with noted Bengali author Buddhadev Bose. Two poems inspired by Bose are found in Oppen’s The Materials. Until recently, however, the extent and nature of their correspondence, and the details of their attempts at intra-lingual translation, have remained unexplored. Their successes and setbacks hold some insight for those attempting intercultural work today.

3

Those unfamiliar with Bengali may not realize how prominent and prolific Bose was, not only as a poet, but as an essayist, playwright and critic. He was regarded as the literary successor to Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for literature. He was also the editor of the first Bengali-language poetry journal Kavita, the Bengali term for Poetry.

4

Bose belonged to what is called the post-Tagore modernist (or adhunik) generation — a Bengali movement which reflected a shift away from Tagore’s Idealism toward more urban and secular themes. They were cosmopolitan and heavily influenced by Western literature, Bose particularly with Pasternak, and later Baudelaire and Holderlin. He also admired Pound, so much so that he published his Confucius: The Unwobbling Pivot and The Great Digest through his Kavitabhavan press in 1949.

5

Politics was an inescapable reality for any writer coming of age in the 1930’s and India was certainly no exception. Bose was a member of several left-leaning groups into the 1940’s, including the Communist-led Progressive Writer’s Union, but later felt that “what had been conceptually liberal turned into various hardened ideologies” (Dyson, xxxiii). Frustrated by a lapse into what he felt was “political cacophony” (AGG, 25) he had a growing sense of disillusionment, then frustration, with Bengali political poetry from the late 1940’s. This lead to a clean break with the Indian Left that garnered him the label of “reactionary,” even “CIA Agent,” from some. The animosity only intensified as the Communist Party rose to power in West Bengal.[1] On the one hand still seen as hard-working and sincere, he developed a reputation for being uncompromising and obstinately stuck in his ways.

6

Compare this with the Oppen’s active participation in the Communist Party. He did not split fully from the CPUSA until late into the 1950’s. In fact, the FBI suspected him along with his wife Mary of being Soviet agents. For a variety of reasons, he eventually became disillusioned with the CPUSA. Nevertheless, he emerged from the McCarthy Era as an unbowed hero to many in the American Left.

7

Despite their different political paths and cultural legacies, both Bose and Oppen distrusted what could be called the “poetry of the moment.” They valued a seriousness and intentionality that would defend poetry against a “furious and bitter Bohemia” (SPDP, 30). Though, while Bose longed for a verse that was “conceived in the soul” (AGG 68), Oppen would seek a verse “confident in itself and in its materials” (SPDP, 32–“The Mind’s Own Place”).

8

While both writers wrestled with strong cultural dynamics, Bose experienced an added tension between his mother tongue, Bengali, and the English language. A mixture of both desire and trepidation led Bose toward the act of translation. Even though he was fluently bi-lingual and heavily influenced by Western literature, he still felt that self-translation into English may be an absurd or futile undertaking. He wrote at one point that he did not, “believe that foreigners can use the language of poetry, and the best we can do will remain pale approximations” (L 3/3/62). It was to George Oppen that he looked to for help.

9

Bose and Oppen first met in New York in 1961 (coincidentally during a tour celebrating Tagore’s centenary year).[2] The initial encounters are documented in three letters written to his sister June Oppen Degnan in early 1961, the only references to Bose contained in the Selected Letters (SL 45). Before they even met, issues of race appear in conversations with James Laughlin who had oddly enough visited Bose in Kolkata several years before. Oppen writes, referring to Bose, “Jay (Laughlin) said he’s old, ugly and very dark. Looked at me thoughtfully and added, and Bengali”. Oppen’s response was oddly dry: “Like Luther (?), I’m not Bengali. That will be a barrier between us” (SL 45, italics added). Unfortunately, such correspondence was all too typical among white American writers, culturally buffered from the offensiveness of their humor. Clearly an awkward exchange of this kind underscores the challenges Oppen and Bose would have to overcome.[3]

10

Nevertheless, Oppen and Bose did meet and connected in unexpected ways. Over the next several months in the Spring of 1961, Oppen became increasingly involved in writing and re-writing several of Bose’s poems, most notably “To Memory” and “Still Life,” as well as “To A Dog,” all of which are from Bose’s 1958 book Je-Aandhar Aalor Adhik, or A Darkness Greater Than Light.

11

It is a great misfortune that the letters from Oppen to Bose are not available [except for the one letter discussed below.].[4] However, Bose’s letters to Oppen are archived, and from them the content of Oppen’s communications from 1961 to 1964 can be inferred. Oppen wrote at least at least five letters to Bose. The first letters deal with publishing concerns: Oppen submitting poems for Bose’s Kavita, Bose seeking to have work included in the San Francisco Review. In another, Oppen requested permission to use Bose’s poems “To Memory” and “Still Life” in The Materials. Other letters concern a memorable visit by Bose’s daughter Damayanti Basu Singh to the Oppens’ apartment in New York.

12

Seven letters from Bose to Oppen survive.[5] They are consistently cordial and express respect for Oppen as a fellow writer and kindred soul. Not long before leaving New York in May of 1961, Bose sent Oppen a quick postcard with his Kolkata address. In a later letter, he recalled a visit to Oppen’s apartment: “the splendid view across East river, your good and strong sherry, and the gracious hospitality of your wife” (L 1/21/62). But the appreciation became more measured after Oppen shared his clipped and layered “translations” that would appear in The Materials. Bose responded, “I felt the essence of my poem in it, although your style is very, very different” (L 10/29/62). Despite the surprising form, Oppen’s efforts were still accepted in good faith. Bose writes, “It is perhaps needless to add how deeply I appreciate this delicate compliment from a fellow-poet; this, more than anything else, shows that the trouble I took over those translations has not been entirely wasted. You cannot know how inadequate the translations are, but even so they have meant something to you, which I find very encouraging” (3/3/62).

13

Later that year, Bose’s daughter Damayanti took a break from her studies at Indiana University to visit New York City and to meet her father’s friend, George Oppen. She remembers, “From the station we walked to the Oppen’s small apartment. We clicked instantly. Mary welcomed me with open arms and I felt totally at home in that small apartment strewn with books and a sweet little bird called ‘bird’ flying around freely” (DBS 2/17/08). Bose remarked at the time that Damayanti “was a little shocked that scarcely any one of our New York friends whom she met knew that her father was a writer; and one reason why she felt drawn to you was that you did. Also, having been raised in a literary household she felt easily at home in yours.” Bose thanked Oppen for his hospitality and added that, in Oppen’s description of the visit, he could feel the “rich human warmth in the words” (L 1/13/63). Unfortunately, the last extant letter from Bose was dated December of 1964 and it may have been their last contact.

14

Initially when the writers were working face-to-face in New York, Oppen’s role was one of an engaged editor assisting Bose with his translation. One can picture the poets word-smithing in the faculty lounge when Oppen writes to June: “Trying to explain to him what the word ‘kissing’ means to me, and why I omitted his line about ‘miles of kissing’ I made smacking noises at him in the hope that he would see what miles of kissing would involve. He didn’t but I attracted considerable attention in the NYU Faculty Club where we met” (SL 48). Oppen then took this role farther, so far as to rewrite an exact translation of Bose’s “To Memory” in English with identical rhyme scheme, keeping lines intact and “without any rime-word which wasn’t in his version” (SL 378). The process finally developed into what could be called an intra-lingual “transcreation” — a textual reworking that seeks to recreate the literary impact of the original for a new cultural audience. The process was successful in many ways, but a full-fledged transcreative process was hampered by Oppen’s lack of Bengali. In this sense language did prove to be a barrier between them.

15

Analyzing the various drafts of the poems by both authors, the basic theme and much of the content are, in fact, consistent, but with some telling differences. Bose’s Bengali original of To Memory 1, or “smRitir praati”, is a Petrarchan sonnet. It is an invocation to a goddess (or debee) who is the embodiment of memory and credited with existence itself. The goddess is described as “slumbering,” having “arctic seas” and although “dark” still holds “inexhaustible riches” — a powerful, female force whose hands are responsible for meaning itself: “in the womb of the mother // Shine the fate of man”.

16

Bose sent two self-translated versions of the poem to Oppen. The first was apparently included in a letter dated October 2, 1962, and is most likely a source text as it includes Oppen’s scribbles. Comments include the words “Primal Space” in bold letters as well as “and in dark is your promise.” He struggles with words “primordial” and “prehistoric” and plays with the concept of galaxies, interrogating the relationship of light and dark.

17

In the end, Oppen transferred twenty-eight words from Bose’s translation including cause, meaning, shore, shine, womb, etc. Some differences: Bose’s “Valueless” becomes “lost to us”; “inexhaustible riches” disappears entirely, possibly words smacking of privilege being muted.

18

More significantly, however, Bose’s “surf of the shore and strife of the day’s changes”–that is, the concept of the shore that needs to be left to enter the timeless peace of memory’s arctic sea, is replaced. Oppen instead invokes “the beaches // That shore the ocean” and ranks these beaches alongside the lute, canvas and marble — symbols of high art. Oppen is not concerned with an ascetic removal from life’s strife, but instead values meaning one finds in more pedestrian places, like beaches.

19

In addition, Oppen removes lines that refer to spiritual concepts that perhaps are too foreign or overtly religious for his taste. He edits out passages such as the “calm horizon where ages join one another,” or trikala (which in Bengali refers to three-part time — past, present, future), as well as a reference to “pre-historic lives” — the concept of reincarnation.[6]

20

There is one word, though, that Oppen inserts three times and which does not appear in any of Bose’s versions — lost. “What your hands have let fall is lost to us.” This is reminiscent of another poem in The Materials, “Part of the Forest” where Oppen writes “to be alone is to be lost,” there explicitly concerned with a masculine self-isolation.[7] Memory is a goddess, but a goddess not unlike a companion that prevents one from becoming “lost” or “alone,” a concept of memory that is clearly female (a Goddess) and inescapably interpersonal. Bose’s first person singular becomes Oppen’s plural “us.”

21

Bose, after teaching in the States from ‘63 to ‘65, would return to India to face the aftermath of the Hungryalist Movement in Bengali poetry,[8] developing an often antagonistic relationship with a movement served as a precursor to American Beat poetry while grating against Bose’s post-Tagore generation. He eventually found an English translator in Clinton Seeley, a University of Chicago Peace Corps alum, who meticulously translated Bose’s novel, Rain Through the Night — a novel brought up on charges of obscenity in India in 1969. Oppen, on the other hand, would move to San Francisco and interact in perhaps a more interpersonal way with a new generation of poets.

22

This was apparently Oppen’s only translation / transcreation exercise. It clearly did not, as Bose hoped, “imitate the individual style of a poet and the peculiarities of the language in which the originals were written” (L 3/3/62). However, it exemplifies poetry’s ability to act as a cultural mediator — always failing in some sense, sometimes offending — and sometimes acting as that bridge that enables us to feel a “rich human warmth in the words” (L 1/13/63).

Letter from Oppen to Bose 19 February 1962:

This letter is copyright © the Estate of George Oppen 1962, 2009, and is quoted with permission.

Buddhadev Bose Timeline

1908: Buddhadev Bose born on November 30 in Kumillah, East Bengal (now Bangladesh).

1923–1931: Studies at Dhaka University, then moves to Kolkata.

1934: Marries high-profile singer Ranu Shome of Dhaka, who, as Protiva Bose, became an equally renowned fiction writer.

1935: Bose’s first visit with Rabindrinath Tagore at Santiniketan. Kavita magazine first published.

1937: From 1937 until 1966, Bose lived at 202 Rashbehari Ave. in Kolkata. This address was dubbed Kavitabhavan, or House of Poetry, the same name as Bose’s press, which published Kavita magazine and other works.

1941: Death of Rabindranath Tagore

1947: Indian Independence; East Bengal becomes East Pakistan and separated from India.

1949: Bose publishes Ezra Pound’s Confucius: The Unwobbling Pivot and The Great Digest in India through Kavitabhavan.

1954: Bose in U.S. teaching at Pennsylvania College for Women in Pittsburgh. Visits Henry Miller in Big Sur in April.

1956–1963: Founds then leads the Department of Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University, Kolkata.

1957: Publishes Language, Poetry and Being Human: A Protest Against the Reports of the Government’s Language Commission defending the Bengali language against Hindi being made the national language. He argues that, while other languages can be useful for everyday life, true poetry can only be written in one’s mother tongue. (Dyson, 177)

1961: Kavita magazine ceases publication after twenty-five years due to a growing frustration over the direction of Bengali poetics and the loss of his close friend, colleague and fellow poet, Sudhindranath Datta, in 1960. (DBS)

1962–1966: Bose’s daughter, Damayanti, studies Comparative Literature at Indiana University. Visits George and Mary Oppen in December, 1962.

1963–1965: Buddhadev and Protiva Bose in the U.S.. Buddhadev teaches first at IU in Bloomington, IN , then at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, IL.

1969: Bose was prosecuted on obscenity charges for Bose’s novel, Raat Bhore BrishhTi (Rain Through the Night), a frank account of marital infidelity. He was later acquitted.

1974: Buddhadev Bose dies of a stroke on March 17th.

To Memory: I

Buddhadev Bose; Translated by the Author c. 1962

(From material in the Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California San Diego.)

Red = words used by Oppen, Blue

= concept discarded by Oppen

I grant

you are the goddess. All that is, is yours.

Hidden in your slumber

is cause, beginning;

Beyond horizons it moves secretly and without awakening;

Yet should you stir an eyelid

there blooms a marvel of flowers

And bright grapes kiss our clay and the earth grows delirious.

The carved stone has no meaning, the canvas is blank, the lute

Itself, until we sail your arctic seas, is mute

In the surf of the shore and the strife of the day’s changes.

Distant on the calm horizon where ages join one another,

And beyond in pre-historic lives and the primordial stark

Azure, like galaxies around us in the womb of the mother

Shine

the fate of man and your inexhaustible riches.

The dark is your province, but more revealing than light is your dark,

And all that your hands let fall is valueless.

George Oppen

(From a poem by Buddhadeva Bose)

Red = concept entirely introduced by Oppen

Who but the Goddess? All that is

Is yours. The causes, beginnings,

Are lost if you have lost them;

But from your eyelid’s quiver

Flowers that are trampled spring

In their bloom before us, and a landscape deepens

Hill behind hill, and the branches

Bend in that sunlight —

The lute has no meaning,

Nor canvas, nor marble

Without you, nor the beaches

That shore the ocean,

The womb of our mother. Galaxies

Shine in that darkness —

O you who are darkness,

A core of our darkness, and illumination;

What your hands have let fall is lost to us.

Still Life

Buddhadev Bose; Translated by the author c. 1964

(From material in the Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California San Diego.)

Red = words used by Oppen ; Blue = concept discarded by Oppen

O apple, what are you? Redness of lips withdrawn

After the kiss, striking the air with luster?

Or an apsara’s rounded breast, darkened with the rapture

And held in the hand of a god whose sight is gone?

So much, yet just begun! This autumn seems unending.

Enough! But more. Even the skin is meshed

In eager sweetness. This glad befriending

Works through the loss undiminished.

And is that all? So think the sleepy ones.

But when some lust-encumbered eye

Sees through bowl and orchard, tears across the veils,

And in a strange spell of light, becomes

In you a forest, a spacious sky —

We too then wish we were something else.

George Oppen; (From a poem by Buddhadeva Bose)

Red = concept entirely introduced by Oppen

What are you, apple! There are men

Who, biting an apple, blind themselves to bowl, basket

Or whatever and in a strange spell feel themselves

Like you outdoors and make us wish

We too were in the sun and night alive with sap.

[1] Damayanti Basu Singh elaborates on the political dynamics surrounding Bose: “Generations after generations of left-leaning youngsters were forbidden to read BB who was labeled as a ’Reactionary’ and a CIA agent! If they could they would have put him under house arrest exactly the way America punished Pound. I see this anti-fascist period of BB’s life when he indeed joined hands with the Communists is now being high-lighted everywhere. It is more important to note how the Communists reacted when he disassociated from them.” (DBS)

[2]2008 is the centenary year for both Oppen and Bose. During the visit, Bose met Allen Ginsberg. Bose was impressed with Ginsberg and wrote that one “could realize that he was on a true mission, at the very least droplets of purity had touched upon him...” (BG).

[3] Jyotirmoy Datta, Bose’s son-in-law, confirmed the fact that Bose viewed Laughlin as a friend. In fact, many Western writers would visit India and would regularly be accepted with open arms. Some would, however, “on return to the safety of western civilization, repay this generosity by writing what they believe are witty or humorous books/articles/poems.”

[4] Bose’s daughter Damayanti Basu Singh made an extensive search of her father’s papers in Kolkata. None of the letters written by George Oppen were found.

[5] Thanks to the Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego.

[6] Bose was not unaware of the tension concerning spiritual matters between Bengali and Western writing. In his defense of Tagore against Pound he wrote: “The only defect Pound notices in him is that his poetry is ‘pious’. This is natural, for in Europe poetry and religion separated long ago; ... In India, this divorce has taken place only recently; it is still a common notion with us that the poet is a religious man...” (AGG 23)

[7] That poem observes that “The young men therefore are determined to be men, / Beer bottle and closed door/ Makes them men.” with “Woman, kids/ In hand. She is// A family”. In that context, Oppen concludes that “to be alone is to be lost.”

[8] For more on the Hungryalist Movement, see Hungryalist Movement: A Photo-Text Album: http://www.kaurab.com/english/bengali_poetry/Hungry-Generation/

Bose, Buddhadev. An Acre of Green Grass. Calcutta: Papyrus, 1948. (AGG)

——— . “The Beat Generation of Greenwich Village.” 1961. Trans. Aryanil Mukherjee. (BG)

——— . Letters from the Oppen archive at the Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California San Diego. (L)

——— . Various Poems in The Literary Review 5: 3. Fairleigh Dickenson University, Spring 1962.

——— . Selected Poems of Buddhadeva Bose. trans. Ketaki Kushari Dyson. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002. (Dyson)

Bosu Singh, Damayanti. E-mail Interviews with Pat Clifford. February 17, 2008 and April 22, 2008. (DBS)

Oppen, George, New Collected Poems. ed. Michael Davidson. New York: New Directions Books, 2002. (CP)

——— . The Selected Letters of George Oppen. ed. Rachel Blau duPlessis. Durham: Duke University Press, 1990. (SL)

——— . Selected Prose, Daybooks and Papers. ed Stephen Cope. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. (SPDP)