| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 12 printed pages long. It is copyright © John Muckle and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice. The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/muckle-hazlitt.shtml

paragraph 1

William Hazlitt’s general definition of poetry is an expansive, all-inclusive, populist one. For him poetry is ‘the natural impression of any object or event, by its vividness exciting an involuntary movement of imagination and passion, and producing, by sympathy, a certain modulation of the voice, or sounds expressing it’ and as such it is the natural expression of any human being seized by a fit of imagination and passion. He tries to suggest the universality of poetic expression by means of an impressive listing that includes street cries and all other forms of elevated impassioned speech as well as written poetry: ‘the miser when he hordes his gold’, ‘the apprentice when he looks after the lord mayor’s show’, and ‘the savage when he paints his wooden idol with blood’. All are poets, and all — at such moments — define themselves and therefore live in a world of their own making. Poetry is, then, in this rousing view, a spontaneous expression of human essence, produced in an involuntary imaginative and emotional paroxysm.

William Hazlit, self-portrait, circa 1802. See Lucy Peltz's valuable comments at the Oxford DNB site here.

2

This is by no means the whole of Hazlitt’s view of art (there are Augustan and neo-classical elements), but it is a useful starting point for a discussion that asks whether poetry is itself by some inherent quality of language, by its subject-matter, or by its forms and its formality; whether it is an essence or an activity, expressive or formal, or whether its origins and raison d’etre are simply as the articulate outpourings of passion — impassioned, self-justifying outpourings, at their best when most selfishly heedless of the counter cries of others: to desist. Many people of course have sea-chests full of this stuff and think it is as good as the best poetry in the world. They have already done better, or as well, by recording exactly how they felt at what seemed like important moments of their life. Whether you like such people or not, for Hazlitt they might be right: that’s all ‘real’ poets are really doing. But how, remaining within his terms, do we get from this vague and potentially embarrassing notion of poetry being everything and everywhere to the complexity and particularity of poetic forms? The key, I believe, is in that crucial element of self-justifying graspiness to which some of us are so prone.

3

Take the line “all that she wants is another baby” from Ace of Base’s justly forgotten dance hit of the 90s. It’s an overheard phrase — we know it already, likely spoken in an impassioned moment, or at least with some brio. But what (if anything) makes it poetry? Is it poetry when spoken, say, as an explanation for wifely dissatisfaction, as a husband’s exasperated outburst, as a bitchy comment, or only when isolated and repeated with a circling vindictive backbeat as the refrain of a pop song? In other words, is it inherently poetic or does it become so only when placed in another situation, in relation to other elements, which let us recognise it as such? Of course, in pop song context, the word ‘baby’ is activated in a different way because we’ve heard it before. We know it means ‘sweetheart’ and therefore the line acquires a certain (slight) complexity of meaning we associate with poetry. Is she looking for another lover or to give birth again? Is she broody or simply sexually restless?

4

I don’t hold out much hope that I will manage to arrive at a conclusive ‘definition of poetry’ in this way, but I will try to explore some of the elements and assumptions that are in play when we consider a poem. In order to do so I will move to a reading of some modern American poems that apparently take such an expressive line on poetry, which I associate with Hazlitt: as principally a kind of paroxysm of uplifted passionate utterance.

5

The first is by New York poet Ted Berrigan, from his collection In The Early Morning Rain (1970):

6

LIKE POEM

(to Joan Fagin)

Joan,

I like you

plenty.

You’d do

to ride the river with.

I take these tiny pills

to our love.

Plenty.

Then I drink up the river.

Be seeing you.

7

This poem is attractive in its apparently casual expressiveness. At first glance it seems so slight and artless, only to have been written to relieve a mood, of ‘like’ for Joan. That is present in the title. It announces itself as a kind of poem, a ‘like poem’ (as opposed to a love poem), of a second order of intensity, perhaps suggesting that it is not a poem at all, merely ‘like’ one. But all these implications of the title, and the opening address to Joan, alert us to, in fact depend upon, our prior knowledge of some formal features of lyric poetry. The charm of its announcement of an emphatic liking for Joan — plenty — comes with an allusion to Huck Finn, to the utopian comradeship of Huck and Jim on the raft, which has become submerged into the vernacular — literary allusion doesn’t need to be direct or even conscious — to innocent companionship, into which Joan is admitted as a comrade.

8

Taking tiny pills to love is a kind of parody of a lovers’ toast or vow, whilst the repeat of “Plenty” takes us into wider cultural contexts, to the historical notion of America as a cornucopia, and an only apparently inexhaustible one, since if one drinks up the river there is nothing left. One can push further into Huckleberry Finn, to the cancelled passage in which a preacher speaks of ‘calamity’s child’, a destructive infant god, Johnny Appleseed in reverse, who strides across and despoils the continent, boiling up the gulf of Mexico, uprooting forests, an image for Mark Twain of emergent industrial America, America the destroyer, which Berrigan appropriates as an image of himself as consumer and despoiler, so that the jaunty farewell of the final line takes on a supplementary air of brutality, indifference — also referring to death (as such salutations so often do in Berrigan’s poetry). The easy charm of the poem, its offer of friendship, carries with it an undertow of desperation, resignation, a sense of brief moments of companionship snatched in a headlong journey to death.

9

Berrigan’s poem is made out of a number of everyday words and idioms: it partakes of Hazlitt’s all-encompassing definition of poetry: gathers, releases, milks meanings from them by performing certain operations upon such everyday elements, operations that concentrate the attention of the reader, alert him or her to wider contexts in which they signify. In this case the operations focusing our attention include a syntax that mimes speech, line breaks, arrangement on the page that bring this into lingering close-up, making its status as utterance clear yet isolating items that invite further meditation. Can this poem, or others from In The Early Morning Rain, like ‘Peace’, in which Berrigan feels disembodied as he walks across town to meet a woman friend “the head riding gently its personal place/where pistons feel like legs/on feelings met like lace”, be said mainly to affirm or to question the centrality of a perceiving subject in poetry? Is poetry an essence, an activity, a way of reading, or what? And what are the implications of Berrigan’s form of address here: the letter?

10

Coleridge’s ‘Letter to Asra’ is the first draft of ‘Dejection: An Ode’. A detailed look at the poet’s revisions shows how radically they alter the nature of the poem. Sir Herbert Read’s account, in The True Voice of Feeling (1953) makes of this Coleridge’s commitment, over the private or inner sources of his art, to the public and impersonal in poetry. Many of his revisions here can be ascribed to feelings of embarrassment, recognitions of ‘bad taste’ (such as almost wishing his children would die), and an attempt to separate out the larger subject of the poem (loss of imagination) from its personal occasion — a passionate declaration of love for Sarah Hutchinson. In the process the addressee of the poem changed several times. First, obviously, it was Sarah Hutchinson, later Wordsworth and/or Dorothy, and finally a more abstract ‘Lady’. Yet for us, as interloping modern readers, the first version seems more modern. We have no difficulty with the personal, we feel we are getting ‘the real thing’; that the ‘real thing’ isn’t composure but disorder, fissures, contradictions: the freedom of versification, desperation and lapses of taste are terrible, but moving; the original letter, unintended for our eyes, seems to speak to us more directly.

11

‘Communism bad, plagiarism good!’ runs one of Berrigan’s obliquely funny aphorisms. But what does it mean? Presumably that one should take what one needs without surrendering to collective meanings, to any consensual cultural idea: an individualistic creed, but one that invites us to take the past as happenstance resource rather than authoritative precedent. The poet assembles his or her own tradition and context. Let us investigate one of his notorious sonnets as a kind of bridgehead between its assembled borrowings and the future: his procedures have in turn been reappropriated and put to use by so many subsequent poets that they have themselves become a kind of clichéd orthodoxy, but poet-guerilla Berrigan’s raids tend to be more involving than those of most of his imitators: there is more at stake in them.

12

Is there room in the room that you room in?

How much longer shall I be able to inhabit the Divine

Deep in whose reeds great elephants decay;

Loveliness that longs for butterfly! There is no pad

He buckles on his gun, the one

He wanted to know the names

And the green rug nestled against the furnace

Your hair moves slightly,

He is incomplete, bringing you Ginger Ale

The cooling wind keeps blowing, and

He finds he cannot fake

Wed to wakefulness, night which is not death

Fuscous with murderous dampness

But helpless, as blue roses are helpless.

13

We can locate lines from Rimbaud, Ashbery, O’Hara: we can unearth names; we can discover procedures of cut-up, collage from Ashbery’s The Tennis Court Oath (1962) reaching back to French modernist poetry; we can explore a syntax of circling incompletion that ‘fails’ to quite sustain a person or situation of utterance. We are offered what Ashbery called ‘the architecture of an argument’, in this case a use of musicality as a substitute for syntax, and a series of ‘rhymes’ and metonymic associations that both multiply and deny locations: one rooms in a room but inhabits the Divine, an undersea realm of rotting organic matter and the debris of spent storms; and beauty demands that and induces all these objects to become its furniture: ‘room’ becomes ‘no pad’, homelessness, uncontainment, except by a sleeping world — and everywhere the elusive organising presence of the poet is ‘wed to wakefulness’, literally there, sweating but incomplete, ‘he finds he cannot fake’ as he transforms himself into a helpless element in his own poem, pinned to the page like a butterfly in a case or a flower on a lapel.

14

Frank O’Hara’s idea, as expressed in ‘Personism: a Manifesto’, of ‘placing the poem between two persons’, is on one hand a way out of public rhetoric, bardic posturing, and on another a deflection of that making public of victimised ego he disliked, perhaps hypocritically, in Robert Lowell’s poetry. Instead his ‘I’ is always being placed, and replaced, in relation to objects, cultural bric-a-brac, and proper names, as if in half of an overheard conversation. But ‘overheard’ gives the game away. We overhear, hence the intimacy and conversational directness of these poems, but our overhearing is being counted upon: otherwise the gaps and fissures in subjectivity with which these poems work have no meaning except as mistakes. As readers we are both the recipients of these letters and the overhearers of them, as though we’d found them in a bundle in his desk drawer, left for us, whoever we are, and are riffling through them. In that sense they are both disguised confessions and a strategically indirect kind of public address.

15

However, it is one thing to point out that O’Hara’s strategies are just that, and another merely to collapse them into previous practices. One thing that made him a particular model and a resource for so many other writers was in part that he made possible such an indirect, unrhetorical comment on public matters — and made the everyday sound so sexy.

15-b

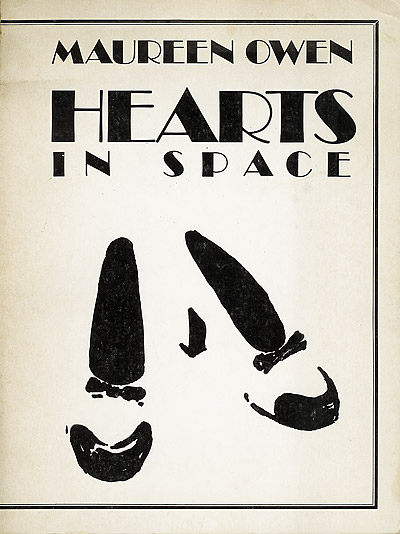

A number of women poets were attracted to personism, amongst them Alice Notley and Anne Waldman, but they were not the only ones. I’ve always liked this poem by the underrated Maureen Owen from her excellent early collection Hearts in Space (1980):

16

BODY RUSH

I’m taking a ride with you in my head

true Love & Oh! the cornfield!

a sweet girl

(Maybe an understanding of the life

will help)

This wind blows over your body

comes across the fields & blows over

my body! Doesn’t that bother you?

TOO MUCH!

I’m thinking of you it’s you in my head you’re on my mind

I can’t get you out of my etc. Can’t shake you loose

can’t stop thinking of you I haven’t washed you out of

my hair I expect you every night Don’t you like

blow jobs? Time is short but I wait for you

I’m crazy about you I’m in love with you

You blow my mind

Come by!

Drop in!

Let’s rap!

Let’s neck Pussy is delicious!

What are you waiting for?

You’re beautiful

lusty handsome

You’re vibes are tremendous!

I can’t believe it!

17

Like ‘Like Poem’ this deploys a fractured double-speaking narrator across more popular terrain than O’Hara’s: its hopeful narrative is buoyant, but there’s an undertow that gradually turns the meaning of the poem on its head: confronting the reality of his lack of interest. It too is made up of speech fragments, snatches of songs, and clichés. Ted Berrigan often implies a constituency of fellow drug users; Owen’s apparent addressee is the desired man, her implied overlooking reader a woman, or group of women; her celebration of sexual infatuation turns around and around the absent man in an attempt at persuasion, then resolves itself into a story about having scared someone off by over-enthusiasm — she might turn out to be a bunny boiler. ‘I can’t believe it!’ she exclaims. That I feel like this. That you’re not interested. We feel she is about to be disappointed but can’t quite let go.

18

What I like about both these poems is their sense of intoxication, their clarity, their apparent slightness, and a cleverness at winning you over (this is funny), inviting scorn (this is nothing), together with an awareness of your response to them and their slow revelation of a hidden complexity designed to ‘turn your head around’ as the woman did in ‘Peace’, so that Berrigan could only go home, drink coke and eat a ham sandwich. As with Berrigan’s poems, but coming from another direction, Maureen Owen’s ‘Body Rush’ occurs at and reflects upon a highly volatile moment in relations between men and women.

19

Maureen Owen’s poem is interesting to compare with the following notebook poem by Lorine Niedecker, unpublished in her lifetime, written at an earlier moment in that history, in other circumstances, one of a number of poems on romantic disappointment and her eventual ill-marriage:

20

The men leave the car

to bring us green-white lilies

by woods

These men are our woods

yet I grieve

I’m swamp

as against a large pine-spread —

his clear No marriage

no marriage

friend

21

There’s something about its exquisite economy of means — a double five line stanza modelled on the Japanese Dohatsu: ‘grieve’ giving the game away (its reference to Pound’s translation, The Jewelled Stairs’ Grievance), and its formal perfection and chasteness of vocabulary — that causes us to linger over the implications of the situation it suggests: the finality and final clarity of a refusal of promised marriage. The poem’s figuration of femaleness as foetid ‘swamp’ around the male perpendicularity of ‘a large pine spread’; the women enclosed in the briefly halted black car (on some formal occasion — a wedding? a funeral? church-going?); and the men foraging on their behalf in the woods of the world are expressed with vividness and restraint: it is a poem ‘about’ patriarchy or about the consequences of being a woman shifted aside, demoted to ‘friend’ in a small rural community of limited matrimonial opportunities; it would be difficult to find a more acid, comfortless use of the word ‘friend’ in modern poetry.

22

Hell is other people, eh? And the poems in the sea-chest of our life’s voyage, if we decide to be our own recording angels, might tell another story than the one we intended to share with the world, or they might, like Niedecker’s, justify us in its eyes if we are persuasive enough — which is to say, if we can persuade a reader that we have been genuinely wronged.

23

*

here come the masses

fed on molasses

ironing away without irony

(Grace Lake)

24

John Carey’s The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice amongst the literary intelligentsia 1880—1939 (1992) addressed itself head-on to what remains a central characteristic of English literary culture: its snobbery towards the working and lower middle classes, its dismissiveness, or disallowal, of wide areas of the social experience of those classes, its predication on a denial of full humanity to ‘the masses’. Beginning with Aquinas and ‘the elect’ in Christianity, he devotes much attention to versions of Nietzscheanism propounded by Shaw, Lawrence, Wells, Wyndham Lewis, and others: the sense of benighted, or worse, subhuman masses and the evident right to rule them of an intellectual übermench. The book is framed as an attack on modernism, characterised here as inherently elitist and in bad faith, valuing the difficulty of its texts in direct proportion to the extent that they exclude a general reader; indeed, he suggests, they are created with precisely this in mind.

25

Now Eliot, Pound, Woolf, Laurence, Lewis and others deserve all they get for their racism, hysterical snobbery and fascist sympathies, but Carey’s later chapters begin to reveal xenophobic tendencies of his own. Barthes is dismissed as a Gallic snob who wrote ‘down’ about popular culture in Mythologies. He even mutters about intellectuals who go on holiday to France and Italy. Finally, he proposes Heaney, Hughes and Larkin as the great poets “in English” of the postwar period, on the grounds that they can be understood by schoolchildren. His final pages seem to turn this populism on its head with curious remarks to the effect that (due to pressure of population) the next century (ours) will inevitably come to view certain classes of human being as vermin.

26

Hazlitt’s ‘Reply to Malthus’ was an attempt to refute an early nineteenth century version of the kinds of belief anatomised by Carey’s book. Malthus’ essay on population similarly denies full humanity to large sections of the populace: and just as Darwin’s ideas would be used later in his century, and in the twentieth, to explain and justify a social version of ‘survival of the fittest’, so Malthus’ application of observations of the cyclical rise and fall of animal populations to human societies was politically motivated as an argument against poor relief. If there were too many of them they should die, since they were fodder, mulch, whose existence was only justified insofar as they were of use to the possessing classes. The powerful, in their turn, were of importance principally in that they had the wherewithal to support philosophers, without whom the earth would not continue to turn — at least, not in any meaningful sense.

27

But Carey’s is not the only account of modernism in Britain. A modest but powerful one is sketched in Glasgow poet Tom Leonard’s pungent short essay: ‘The Locust Tree in Flower, and Why it had Difficulty Flowering in Britain’ (1976). Leonard suggests that hostility to William Carlos Williams’ work — and to poets who attempted to import his poetics — arose because those poets were proposing that language is another thing in the world rather than merely a neutral medium in which the world appears, a proposition which he claims as such challenged deeply-held British assumptions about authority, ‘bought’ linguistic register (RP) and ownership: that certain tones and locutions have a privileged access to the real. Carey might heartily agree with this statement, but Leonard’s version of the political meaning of modernism turns Carey on his head. Both versions of the political meaning of modernism are tendentious distortions — and both have a quality of paroxysmic political anger.

28

Tom Leonard’s poems are mostly Glasgow speech miniatures, but they have none of the fluency or rolling on quality of speech: they are more like samples that have been meditated upon in order to extract their social pith. “Hawfa pakora/is better than nay samosa” is more like “all that she wants is another baby” than the aristocratic flower-arranging that has rightly or wrongly sometimes been associated with modernist poetry. ‘High’ modernism often defined poetic language in opposition to the instrumental, discursive ‘newspaper’ language of prose, a position that has its origins in late Romanticism and finds fuller expression in Mallarme’s Un coup de dés essay and reappears in Russian Formalist writings, where ostragenie or estrangement is taken as the sine qua non of poetic language — which admits the social at one remove. Walter Benjamin is remembering this poetry/prose distinction in his One Way Street piece about art and documents, ‘Thirteen Theses Against Snobs’:

29

VI. In the artwork subject matter is a, The more one loses oneself in a document

ballast jettisoned during contemplation the denser the subject-matter grows

30

However, modernist poetry’s refusal of public ‘voice’, its foregrounding and playing with the word’s status as sign, doesn’t exclude the social but can offer the reader a different relationship to that element. By isolating a word in time and meditating on it, we may be able to bring its cultural and historical freight to a later day. We may discover that writing for a few people, or in the case of Lorine Niedecker, for one who is a fellow poet: Louis Zukofsky, has led to intimacy, unguardedness of a kind, and that this writing is therefore more deeply revealing of how it was to be, then, what her preoccupations and sense of self were, what was at stake in that moment and in that structure of feeling. Every poem is both a document in the history of writing and a historical document. Looked at in this light they may invite an attentive reader to weigh them in new ways. A coterie poetry may even be better at doing this than verse which rhetoricises about the public matters of its time, but a more even-handed way of looking at these positions might simply comment that poetry which is intimate and doesn’t much care for public strut can exist in all traditions.

31

Finally, to return to Hazlitt, for him the preeminently, definingly human quality is ‘passion’; not much of a cause for celebration, we might object, since by his own definition it includes both an innate liking for mischief and a perverse revelling in suffering for its own sake. The qualities he most admires or values in human beings: incorrigibility, bloody-mindedness, intractability, are also those that most stand to prevent achievement of his radical social ideals, contradicting his never renounced commitment to revolutionary republicanism.

32

“The only faculty I do possess is that of a certain morbid interest in things, which makes me equally remember or anticipate by nervous analogy whatever touches it; and for this our nostrum-mongers have no specific organ, so that I am quite left out of their system. No wonder that I should pick a quarrel with it! It vexes me beyond all reason to see children kill flies for sport; for the principle is the same as in the most deliberate and profligate acts of cruelty they can afterwards exercise upon their fellow creatures. And yet I let moths burn themselves to death in the candle, for it makes me mad; and I say it is in vain to prevent fools from rushing upon destruction.

“( ... ) (Coleridge) could not understand why I should bring a charge of wickedness against an infant before it could speak, merely for squalling and straining its lungs a little. If the child had been in pain or in fear, I should have said nothing, but it cried only to vent its passion and alarm the house, and I saw in its frantic screams and gestures that great baby, the world, tumbling about in its swaddling clothes, and tormenting itself and others for the last six thousand years! The plea of ignorance, of folly, of grossness, or selfishness makes nothing either way: it is the downright love of pain and mischief for the interest it excites, and the scope it gives an abandoned will, that is the root of all the evil, and the original sin of human nature.” (from ‘On Depth and Superficiality’)

33

In ‘On the Spirit of Obligations’, and in many other places, Hazlitt is a memorable lamenter of human faithlessness, perversity and selfishness — plainly he is not such an advocate of unrestrained passion as all that — but still he makes ‘passion’ in its most selfish sense the defining human quality and the motor of everything. It is a little like a Georgian version of Freud’s libido — and also includes thanatos. Hazlitt himself continually acts in the grip of it, but it is most vexacious to him, and the length at which he elaborates its instances in human behaviour suggests (as well as being paid by the word) a disturbed fascination with this endlessly abundant perverse human substance that so mocks at the good efforts of reformers.

34

‘Passion’ — articulated against ‘reason’ in Hazlitt’s version, as pure signifier of human value — is a term that is ascribed to a perverse human ‘essence’ that, perversely but necessarily, it continues to celebrate. But wolves are just as passionate, so are monkeys. We think we no longer believe in the Enlightenment; neither did Hazlitt — he was always mocking Bentham and other progressive social engineers. But if so we have no other ground upon which to accord others their dignity than to accept their passions. To try to beat a path across this rocky terrain is to take a trip on which one must question everything, pick up everything, look at it — and, unless we can embrace every kind of wrong-headedness — put it carefully back in its place. But poetry is outpourings. Poetry remains distinct from prose and high-flown parliamentary speech-making precisely when it is paroxysmal: perhaps only then can it really deeply provoke us.

35

And perhaps such restricted or chastened definitions of the human are good for us: a ground on which possible better futures might be built. We’re all in it together. What else is there? Malthusianism cuts away the ground on which others might be accorded any meaningful rights — what does it matter if a few million of the teeming spark-blobbies of theoretical anti-humanism are snuffed out? Like Malthus’ prototype social planners, the western world’s current justifying philosophers know that the Earth will soon put forth a few million more of these creatures. We are supposed to be better informed now than by the rudimentary social science of Hazlitt’s day, but our notions of the ‘human’ have sometimes been said to have been rendered dysfunctional by the scale of suffering our media reveal, just as they were already wishful thinking in the 1820s — an era that accepted cruelty and visible death on every street corner, just as we do on our TV screens. We blame the failure of our governments and our opposing intellectual traditions, quashed just as Godwin’s optimistic anarchism, the English Jacobins and the Chartists had been quashed. And if Hazlitt couldn’t refute Malthus’ justifications of power, neither can we, not really. Poetry is just cries, self-glorifying and pained. Philosophy — and the police — will do what they like with us.

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings (New Left Books, 1979)

Ted Berrigan, In the Early Morning Rain (Cape Goliard, London, 1970)

David Bromwich, Hazlitt: The Mind of a Critic (Oxford, 1983)

John Carey, The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice Amongst the English

Intelligentsia 1800—1939 (Faber and Faber, London, 1992)

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Poems

Anthony Giddens, The Transformation of Intimacy (Polity, Cambridge, 1983)

William Hazlitt, Selected Essays, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (Nonesuch Press, London, 1930)

Tom Leonard, Intimate Voices (Galloping Dog Press, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1983)

Thomas K Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1985.

Maureen Owen, Hearts in Space (Kulchur Foundation, New York, 1980)

Jenny Penberthy, Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky, CUP, 1993

Herbert Read, The True Voice of Feeling: Studies in English Romantic Poetry (Faber, London, 1953)

William Carlos Williams, Collected Poems (Carcanet Press, Manchester, 1985)

John Muckle

John Muckle was brought up in the village of Cobham, Surrey, but has spent most of his adult life in Essex and London. His most recent books are Cyclomotors (illustrated novella) and Firewriting and other poems (Shearsman Books, 2005).