| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 24 printed pages long. It is copyright © Barry Gifford and Noel King and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice. See our [»»] Copyright notice. The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/iv-gifford-ivb-king.shtml

JACKET

INTERVIEW

‘The Truth is in the Work’

Barry Gifford

in conversation with Noel King

Berkeley, California, 27 June 2007

You can read three poems and a play by Barry Gifford in this issue of Jacket.

paragraph 1

Noel King: You have been involved in the ongoing Francis Coppola On the Road film project. I read that you had suggested Gus Van Sant as a possible director. Is that project still happening, or is it lost in pre-production hell?

2

Barry Gifford: Unfortunately, that has been the one biggest disappointment I have had in dealing with the movie business. Francis came to me and asked me to write the screenplay for On the Road. He’d had a number written before mine, and probably even after. I know that he and Michael Herr wrote one afterwards. Anyway, I wrote the screenplay, this must have been 1995 or so, and it was all set to go with Gus Van Sant directing, Francis producing. Everybody wanted to be in the movie, it was green-lit at Columbia Pictures, and then the deal fell apart due to Francis’ own conflicts with Columbia Pictures over another deal.

3

And basically he took On the Road with him and so the movie was not made at that point. I know he’s got another group of people working on it now, he’s had several over the years, it’s just too bad that we didn’t get it done. I thought that really was an appropriate time, I thought Gus was the right director, completely, and Gus and I worked on the revisions together.

4

Anyway, that’s what happened there. It was a privilege to be asked, and to work with Francis, and he told me that he liked my script very much. So did Columbia Pictures. So I did my part but with a movie, you know, there are so many possibilities about things going wrong, more than go right, and the politics of it gets involved, and one thing and another. Maybe one day it’ll get made.

5

NK: You have lived in San Francisco for a long time, while also having spent considerable time in London, Paris, Rome, and your memoir writing recalls an early childhood of travelling, hotel rooms, moving from Chicago to Florida. What drew you to San Francisco and what changes have you observed during your years living here?

6

BG: I originally came out here to get a ship. That was January 1967. I was working as a merchant seaman and had been living in Europe for quite a while, since 1965, in London and Paris, working on ships, and then I came out here because I wanted to go to the Far East. And January 1967 was an amazing time to come here, so I stayed for five months and then went back to Europe, to London and Paris again, and came back in January 1968 and knew that I wanted, at least for a while, to base myself here, because I knew that I liked San Francisco. In those days it wasn’t crowded, it was cheap, and beautiful, very Mediterranean, very European at that stage, with a very liberal atmosphere. And one other important thing about first coming to San Francisco, I really felt that Asian connection, it’s one aspect I always enjoy here. So all those things added up. Plus there was a very rich labour history, and literary history, and I loved the climate. Low humidity, no bugs! All those things contributed to it.

7

Then I met a girl here and started a family and so my kids were all born here and have grown up in San Francisco, and I’ve used it as a base ever since. I’ve lived in other places, in Rome and Paris, I spend a lot of time in New York, and of course I go wherever I need to be for work. Yet I’m always happy when I come back here. So San Francisco has changed insofar as it’s become overcrowded and much more expensive, like most places. But most of my kids are around, there are grandchildren now, and, basically, if you’re ‘grandfathered in’, the way I am, it still suits me, so it’s still the most comfortable place for me to be based.

8

NK: I have read that you had a relationship with an Italian actress and spent a few years dividing your time between the US and Italy.

9

BG: I spent four years travelling between here and Rome but that ended ten days before 9/11. I came back here for my oldest boy’s wedding, and didn’t go back. But I hadn’t intended to go back, I was ending that period of my life.

10

NK: Your writing makes easy reference to several other languages and cultures, most obviously French and Mexican. Which languages other than English are you most familiar with?

11

BG: Well as my old friend Daniel Schmid, a Swiss director, once said, ‘I speak six languages, all imperfectly!’ In my case I can’t say I’m fluent in any language other than English but I do speak Spanish, French, Italian, even some Japanese. The thing is that when I go to a place and spend some time there, I make the effort. And look, language is what I work with. I have a pretty good ear and even if my vocabulary isn’t always as extensive as it should be, or as I would like it to be, I’ve often been complimented by native speakers on my accent, and that’s just because I listen.

12

When I get into something, I tend to go to the end of it. When I came back here from Europe I started going to Mexico a lot, spending a lot of time in Mexico City and Veracruz. It was closer than Europe, it was a little bit easier. And I still go wherever I need to go for my work, that’s the nature of the business.

13

NK: How did your Bordertown photo-book collaboration with David Perry come about?

14

BG: Bordertown was a great project because an editor then at Chronicle Books in San Francisco–who were doing beautiful visual and photo books–came to me and offered me a great deal, and said we’ll pay you to go wherever you want and you choose the photographer. I chose to do a photo and text book, which I’d never done, and I chose to spend the time on the US/Mexico border. At that time I was writing a lot about the border, I’d written 59 and Raining, and that was made into a film, Perdita Durango, and I wrote The Sinaloa Story. I’d always been drawn to the area but I really wanted to explore it in more detail. And so David Perry, the photographer, and I spent quite a bit of time on the border, driving all over the place, and the result was Bordertown. And then a second book version was published, The Four Queens, in a very, very fancy, very expensive, limited edition by a San Francisco gallery, Gallery 16, for $1500 a crack, one of those things. Bordertown is a book I’m very proud of. It’s won many awards, and I think David Perry is, since Robert Frank, one of the great black and white photographers of our time, underrated perhaps, and photography is a difficult business to be in. I don’t know so much about it.

15

NK: Your website contains a documentary, available for viewing, called Bordertown: A Journey with Barry Gifford (Georges Luneau: France: 1999). That’s where I learned the term ‘wetback’ was initially applied to cattle before being applied to Mexicans wanting to move into the US, so it was a doubly offensive term.

16

BG: That was made for French television. Georges Luneau was the director, and again, we trawled along the border and re-enacted some of those scenes, and went back to some of the places that David Perry and I had been, and some other places. The French and the Italians like to do these documentaries, like the Italian feature film, Barry Gifford: Wild at Heart in New Orleans (1999: 80 mins) which I really like. They like to put the writer in his milieu and since so much of my fiction has been set in New Orleans, that’s why the Italians decided to use it as a background, pre-Katrina. I was actually just back there recently. The same is true of the French, they wanted me on the border because it’s the setting for a lot of my fiction.

17

NK: They like putting the writing in his fictional situ, as a French TV company did when Mathieu Serveau made a film on (and with) Jim Crumley, Esprit de la route (France: 2002).

18

BG: Exactly.

19

NK: In The Devil Thumbs a Ride and Other Unforgettable Films (later re-issued as Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir) you mention watching Robert Aldrich’s film, Autumn Leaves, and connect it with your recollections of a time with your mother and one of her husbands, and you say that the song in that film was one of your mother’s favourites, along with “La vie en rose.” And your story, ‘The Ciné’, from Do the Blind Dream? is a lovely playing out of a scenario involving a young boy, his father, and the movies. Leaving aside, for a moment, your extensive screenwriting, your fiction writing seems very connected to the history of cinema, with movie-going as a very important experience.

20

BG: First of all, when I was a child, my mother loved to go to the movies, especially foreign films, and she used to take me with her, all the time. So early on I was really inculcated with this love of cinema and an interest in the way people lived. And even if, as a very small child, I didn’t understand necessarily what was going on at the movies I retained the images in my head, and the dialogue. And I became interested in the way people spoke. Also, I was left alone a lot as a child, so I would stay up all night watching movies, and that’s really where I developed my sense of narrative, and a very visual sense of how to tell a story. I think that’s really where it began, and I’ve retained it ever since. I’d never really thought about it in terms of writing for the movies because that was not my initial orientation. I started by writing stories, and that was it, it was all about telling stories, and using my imagination, being free to do so, and it wasn’t until much later that the movies came to me, basically. My novels began being bought for film, and then I began being asked to write for the movies.

21

Actually I was asked to write for film quite early on, right after my novel Port Tropique came out (1980). I wrote the screenplay for Port Tropique, which was deemed unacceptable for film. But it was better than the couple written subsequently by so-called professionals. I say that now because I re-read it again recently and I realise it’s better than the other ones that were written. In any case, that movie never got made. So early on I was asked to spend some time in LA, in Hollywood, to write dialogue and to doctor scripts, and I turned it down. My children were really little and I wanted to be around here and have the time with them. The money didn’t mean so much at that point, not that I didn’t need the money, I absolutely needed it, but it just didn’t seem right. I said, when I really do this, I want to come in the front door, and that’s what finally happened a few years later.

22

NK: Your collaborations with David Lynch are celebrated and ongoing, and your piece on his Blue Velvet in your initial collection of essays on noir films, The Devil Thumbs a Ride, was slightly critical of that film.

23

BG: We had talked at various times and talked about his work or my work, and I’m sure it came up but I don’t think it was an offensive essay.

24

NK: Not at all.

25

BG: I was just telling my reaction to it. And I have to say something about that. That essay was written off the top of my head after seeing Blue Velvet the first time, and then when I saw it again later, a couple of times, I revised my opinion of it to some extent. My initial impression is still the same and that should never be tampered with. Lynch is so affecting, it’s a tribute to David that he can so profoundly affect people through the use of images and sounds. Certainly my experiences with him have proved that. I saw him again just recently, I went to a screening of his recent film, Inland Empire. In any case, I love David and I love what he does.

26

NK: Well it’s been a great collaboration across film (Wild at Heart, Lost Highway) and TV plays (The Hotel Room Trilogy, two of which, “Tricks” and “Blackout” Lynch directed). At the start of The Devil Thumbs a Ride, you say you imagined yourself in the situation of the 1950s Cahiers du Cinéma critics, writing at 1 am in a café or at a kitchen table. You have some great, pizzazy, moments of vivid description and re-narration in these essays, such as your description of the denouement of a scene in Jean Negulesco’s Roadhouse, “It’s the wigged out Widmark who takes the pipe.” And Elmore Leonard said that many of your essays on these films were better than many of the films, and that is coming from a guy who would really like those films.

27

BG: Well, I’m a writer and it’s always primarily the use of language. One thing that I’m always concerned with is the preservation of language. For example, when I wrote Wyoming — which was published on its own as a novel and now is included in Memories from a Sinking Ship, and which was also made into a play, which I adapted here for the Magic Theatre in San Francisco — I was really doing it to preserve the language of the period. The book is set in the early and mid 1950s in the Midwest and south of the United States but in fact the mother really is using a vernacular from the 1920s and 1930s. And I found that a lot of that language was disappearing, a lot of expressions, a lot of the manner of speech, all of that, and I really wanted to preserve it. And I did so by writing a whole little novel, if you will, in dialogue, except for one chapter, which is not included in Memories from a Sinking Ship, and a short film was made of that too, Ball Lightning (Amy Glazer: 2002), mentioned on the website. That’s always been important, so I suppose the kind of writing that’s done in my essays, as well as elsewhere, is always going to contain this element.

28

NK: Yes, that close attention to historical details of everyday speech, aspects of the quotidien.

29

BG: Correct, so I’m always trying to have the language relate to the detail of the time, of the film or whatever I’m writing about.

30

NK: You have had a long involvement with all aspects of publishing, from small presses on the west coast to big houses in New York, and your founding of Black Lizard Books. How did you initially come to connect with small press culture?

31

BG: I had a great introduction to this. My first book of poems was published in London. I was 20, and when I came to San Francisco I was a poet basically, and I was introduced to printers, really fine, letter-press printers. My first books in this country were done by a small press in Santa Barbara, Christopher’s Books (run by Melissa Mytinger), and the books were printed by great printers like Graham McIntosh and Gary Albers. My first book of stories, A Boy’s Novel, was done in letterpress, just amazingly beautiful. And I had friends here like Clifford Burke, Holbrook Teter, who were very famous letterpress printers. They worked for Andrew HoyeM and they would print broadsides, you know, poems on fine paper.

32

NK: Chapbooks!

33

BG: Yes, and so I really fell in love with printing itself, making finepress books. I had friends in New York who were also involved in this, so just seeing the word on the page, how it was arranged, how it was designed, how it was printed, all meant a lot to me. It was just this whole process of book-making — not the kind my father did (this said with a smile) — but the actual printing of books, that interested me, and still does. So, small presses, such as they have been, have been very important to me and I just felt I needed to keep my hand in, with my books of poems or certain other chapbooks, things like Read ’Em and Weep (Dieselbooks, 2004), Brando Rides Alone (North Atlantic Books, 2004) that I can redo later for inclusion in a larger collection to be published in New York or wherever. So I’m still into that. We might be at the end of the Gutenberg era, for lack of a better term, given the technological advances, if you want to call them that. I’m not, strictly speaking, a Luddite, but I think people are going to be missing a whole lot and in very short order. So I’m glad that I came in when I did, during the literary era, even the last stages of it perhaps. It’s been a noble effort and I’m still interested in it.

34

So that was at the base of starting something like Black Lizard. Or even years before, back in the mid 1970s, when Gary Wilkie and I had a little press called The Workingman’s Press, we published Allen Ginsberg and various other people in these sort of chapbooks, these small books. But everybody was doing that, everybody who was involved in the poetry world and all that. I was never really a part of the poetry world per se just as I’m not a part of any of these worlds really. I sort of have one foot in a bunch of them and just go where I want and do what interests me.

35

NK: On San Francisco and small presses, Paul Auster began out here with his first books of poetry and the initial individual volumes of his New York Trilogy didn’t he?

36

BG: Yeah, sure, Paul, who is an old friend of mine, began as a poet and a translator and we had a very similar arc, and then he got into movies later.

37

NK: To recall for a moment your Black Lizard publishing project (1984—1989) you must be happy to know that after falling through the cracks during the transition following the sale of Black Lizard titles, those already published and those commissioned, to Vintage/Random House. Elliot Chaze’s Black Wings Has My Angel is now available as a print-on-demand title from BlackMask.com/Disruptive Publishing.

38

BG: I just co-wrote a screenplay for it.

39

NK: I liked your essay about going to meet him, “Black Wings Had His Angel: A Brief Memoir of Elliot Chaze,” originally published in Oxford American in 2000, and now available in your collection, The Rooster Trapped in the Reptile Room

40

BG: I did meet Elliot Chaze and his novel, Black Wings Has My Angel, was the last purchase I made for Black Lizard Books. Then, when Vintage/Random House took it over, they chose not to publish the book, much to my dismay, and to Elliot Chaze’s dismay. And they blew it basically, because that was the quintessential Black Lizard book and I was sorry that they did not recognise that. But of course it’s attained a semi-legendary status, partially due to my own efforts, and a producer in New York now holds the screen rights and, as I said, I just collaborated on the screenplay, so I hope they make the film. A film was made years ago by Jean-Pierre Mocky in France, Il gèle en enfer (1990). I never saw it but I heard it wasn’t very good. Lynch and I wanted to do it. I had Lynch read the novel and he was all excited about it, but I couldn’t get the rights. Elliot had sold the rights for $10,000 or something to Mocky. I don’t blame him, he probably needed the money at the time. Anyway, it almost became a Lynch-Gifford film, it came very close, we would have done it.

41

NK: The range of your writing is very impressive. You write poetry, stories, novellas, novels, memoir, essays, biography, screenplays, and I see you have written a libretto and have a Japanese connection.

42

BG: In the early 1980s I was interviewed by a Chinese scholar who came to the US. He was writing a book for a publisher in Beijing, and he wanted to interview me about my poetry. He was interviewing various American poets whom he felt bore a relation to, and understanding of, the Chinese and Japanese poets throughout history and he came to interview me, which was nice. I had already been in Japan, I’d spent a couple of months there in 1975 but I’d always been drawn to the Asian poets, Li Po and Tu Fu, certainly, introduced by Ezra Pound and others. Then I really started reading Su T’ung-Po and Wang Wei, especially, in translation. I don’t read Chinese, although I have studied Chinese written characters.

43

Then, years later, Toru Takemitsu, the Japanese composer, asked me to write a libretto for his opera, which became Madrugada, and was completed by Ichiro Nadaira after Toru passed away. And I thought Toru had asked me to do this because of Wild at Heart, the novel and the film, which was the most famous of my works, but he said, no, no, I ask you because of your poetry, your sensibility is close to mine, I’m a poet too. And I had not consciously recognised Takemitsu though I had heard his scores for dozens of films. He did ninety film scores, for Kurosawa (Ran, Kagemusha) and Teshigahara (Woman of the Dunes) and Philip Kaufman (Rising Sun), all that. So I knew his music in that sense but was ignorant of the fact that he had composed those scores. He was one of the most honoured international composers, and I came to know him very well, and I was very flattered that he had approached me not because of my novels and films, but on the basis of my poetry. He knew of my relation to films and thought we could work together, and we did work well, and completed the libretto together. So I guess that Asian sensibility or whatever else was the attraction to those poets, paid off.

44

NK: You have practised in various forms and registers of writing that range from the avant garde to literary fiction to so-called genre writing. Have you noticed any difference in how your work is received in the US as opposed to Europe.

45

BG: The French don’t seem to make much of a distinction between the two kinds of writing; though it was the editor Marcel Duhamel who created the série noir at Gallimard, in 1945. If it makes it easier to classify in a bookstore or a library, fine, but I think we’ve seen cross-over from so called genre fiction to literary fiction, for so long now. I’m a literary writer but I’ve also worked as a journalist. Those category distinctions, that’s for the academics to work out.

46

NK: When you start a new piece of writing, at what point do you know what genre it will be in–poem, novella, short story? In other interviews you’ve said you listen, and wait for a voice to guide you.

47

BG: First off, it’s great to have these various forms available to me to choose among. A thought occurs to me and it expresses itself, whatever the feeling or the story is. It might become a song. I still write songs. I came to poetry from song lyrics; or it might work better as a poem, a play, a novel, a story, or a film script. And sometimes it gets a little confusing, in that I might have chosen wrong in the beginning and I see that it will work better in another form and then I’ll switch.

48

NK: What is an example of that?

49

BG: I started writing something that I thought might be a film treatment and then I realised that what I really wanted to do with it was a comic book, or I wanted it to be a graphic novel. So I started one called Strange Cargo, and now an illustrator is doing the drawings for it. There was a graphic novel made out of Perdita Durango, so it’s possible, obviously, for an idea or a story to be exploited in more than one medium.

50

NK: And Auster’s City of Glass was in that “Neon Lit” series, and another title came from the noir novel and film, Nightmare Alley.

51

BG: I loved Scott Gillis’ drawings for Perdita Durango, I loved the art work and I liked the presentation in Art Spiegelman’s “Neon Lit” series. I think Auster has recently reprinted his graphic novel version of City of Glass but I never reprinted Perdita Durango after that series stopped, because I didn’t like the script, which I did not do. Maybe I will reprint the book some day if I can get around to writing the script myself.

52

NK: On the matter of the film of Perdita Durango (Alex de la Iglesia: Spain/Mexico/US), I saw it on theatrical release in Sydney at the time of its first release and initial circulation and so I was surprised to read only a year or so ago in Film Comment that it was listed as one of their films ‘requiring a distributor’. I had assumed that if I saw it in Australia on its original release, it certainly would have circulated theatrically here in the US.

53

BG: I wrote the first screenplay for it, I still get the lead screenplay credit, but unfortunately it was never given a theatrical release here. There were legal problems about product usage and images of Burt Lancaster and Gary Cooper and permissions hadn’t been cleared.

54

NK: So they didn’t have copyright for some territories?

55

BG: They were really stupid about that because it was supposed to be the film that made Javier Bardem a star here, and he did so well as Romeo Dolorosa. And of course Javier became a star anyway! He’s a pal of mine, a wonderful guy, a great actor. Anyway, in the US Perdita Durango was only released on video, under a different title [Dance with the Devil], and some of the most important parts were cut out. So unless people go to see it at some special screening like at the Walter Reade Theatre in New York, or various repertory screenings, they can’t see it. But they can get the UK DVD, which is a complete version of the film. I’m told the film was sold to the world and was released in at least forty countries.

56

NK: A friend of mine is a great fan of the film you co-wrote with Matt Dillon, City of Ghosts (Matt Dillon: 2002: 97 mins). He really loves the music.

57

BG: That soundtrack is all Matt Dillon’s work. He spent a great deal of time on it and I think it’s a wonderful CD.

58

NK: Are you two likely to collaborate again?

59

BG: Yeah, we talk about it. I was just with Matt in New York and we’re working on a new story, but it takes time getting together, getting our schedules straight, and then getting the money, but we’ve talked often about working together again.

60

NK: What is your daily writing regimen? When do you write, and what is your process for rewriting?

61

BG: Very early on I would write late at night, write any time, but after I started a family, I decided what I wanted was a more regular routine so I could sit down and have dinner with the family, with my kids. Of course the kids are all grown and gone now but I’ve maintained that same schedule, which is that I get up very early, and that’s when I write, and I’m finished by 1 o’clock in the afternoon, and then I have the rest of the day. I think I’m certainly not alone in this, and it’s worked out very well for me. But as years have gone on, of course, I’m interrupted more often and I have to avoid the telephone as much as possible, so I have an assistant who can take care of a lot of that, let alone emails and that sort of thing. I don’t even have a computer.

62

NK: You have a typewriter there on your desk, covered by a tea-towel with a map of New Zealand on it.

63

BG: I still write in longhand, then I put it on the manual typewriter, then I give it to my assistant to put it on disk, so that’s the process. And I find that writing early in the morning is still the best time for me, it’s quiet, so I’m up by 6 o’clock still, virtually every day, that’s my writing routine.

64

NK: Well, it worked for Hemingway, as you’d know. He’d write early, standing up, then go for his walk around Paris.

65

BG: My mind works the best in the morning. I know a lot of people who can’t have a clear thought until noon, and that’s fine, it depends on a person’s rhythm, and what happens, but I have a very, very rich dream life and often the dreams carry over into my first waking hours, and somehow that transports me and puts me into that state where everything is suspended other than where I’m at in my writing mode. So if I’m working on a sustained piece, a novel, say, that’s where I want to be, and I can’t wait to be back there every day. But I also understand if I push it too hard, if I lean too hard on it, I can be wasting my time. I have to sort of follow that but stick with it. As Charlie Willeford told me many years ago, writing a novel is like building a house, every day you lay a few bricks, pretty soon you’ve got the house. And for lack of a better explanation that’s pretty much how it works when you’re doing something like that.

66

NK: So how does the process of re-writing work for you, as you move from a longhand version to manual typewriter to having someone put it on disk?

67

BG: Well, as I said, I write in longhand and when I go over what I’ve written in longhand I make changes, corrections, additions, so that’s a second draft. Then I put it on a manual typewriter, so that’s a third draft, and then I make corrections on that, so that’s a fourth. Then I make a clean copy, so that’s a fifth. So before it is put on disk there have been five drafts, and all very natural, and then I’ll make further changes, not so extensively. There does sometimes come a time when at the point I’m ready to write, it’s pretty much all there in my head. I just finished the seventh Sailor and Lula novella, The Imagination of the Heart, which will come out next year in the US and France. That’s an example of a cohesive work that required very little revision.

68

NK: So it might come out in French first?

69

BG: Well I don’t know if it will come out first in French but the French are always on me for stuff, I publish fairly often in La Nouvelle Revue Française, and obviously all the Sailor and Lula stuff is very popular there, so it’ll probably come out around the same time because it has to go through the process of translation. It’s not very long. That’s a sort of situation where I know these characters so well, I hadn’t planned to go back to them, necessarily, but now Lula has her voice and she gets to tell her story her way, and she’s eighty and it basically just flowed. I didn’t have to revise it much at all, although I did revise it. That’s the kind of thing where the voices are so familiar and the people are just talking. And my job is to get it down right.

70

NK: That sounds a bit like ‘the writer as amanuensis to the characters’ idea. Tarantino once said he was like a court reporter when he got his characters talking ...

71

BG: I don’t mean to be disingenuous in this by saying I’m taking dictation. I’m creating, inventing and making all sorts of choices all along, but nevertheless Lula’s is a very strong voice, and I know her intimately.

72

NK: Do you have a sense of which European and other literary cultures respond best to your work?

73

BG: Well, the Latin cultures respond very strongly and positively to my work. I had an email recently from a guy in Spain. I have a loyal readership in Spain, France, Italy, and Mexico; I don’t know, maybe it’s because some of my characters have Latin names, I’m not sure exactly why. Although some of my stories are set on the Mexico-US border. But I had this email recently from a guy who was a close friend of the Chilean writer, Roberto Bolaño, who is now having his ‘moment’, getting his works published here.

74

NK: Very much so, in the wake of the translation of The Savage Detectives.

75

BG: Bolaño died in 2003. I didn’t know him and this guy writes and says Roberto was a big fan of your work, he read all your stuff when it came out, especially when he was living in Spain, have you read any of his work? This was before his main works had been translated. I think I’d read a short story of his that came out here. So that was nice to know.

76

I was told a story once. A woman was on a train and it turned out that the guy she was on the train with was Thomas Pynchon, and she said, you’re a writer, I’m friends with Barry Gifford, do you know his work? And apparently he said, oh yes, he’s a good writer, but I think perhaps he publishes too much. I don’t know if that is a true story, but in any event I admire his work too.

77

It’s always nice to know that intelligent writers and readers from other cultures are following your work. You can be halfway across the world, just as you are now. I mean, I write in English, you speak English, but you speak Australian. I speak American, we know the differences and understand the distinctions, I’m using my argot du milieu, the way you do. I don’t even know how many of my books are translated into these languages. I think it’s something like twenty-eight languages, but how are they doing this in Czech or Rumanian? I mean, you write from a particular place and a particular time. Boy, what a struggle that must be for the translators. So you’re only as good as your translator in these various countries, especially if so much of the dialogue is in dialect difficult even for American readers to parse.

78

NK: Are you in touch with your translators in these places, do they seek you out for advice?

79

BG: The only other language that I can read fairly well in is French, and I have a great translator there, Jean-Paul Gratias [Amazon.france lists translators such as Clelia Cohen, for Do the Blind Dream, Claire Cera for Wyoming; Laetitia Devaux for The Sinaloa Story], who’s done most of my books, and now he’d doing the new Sailor and Lula one. I have had other books translated there, Wild at Heart for example, and they need to retranslate that book, there were some problems with the original translation. I became friends with that translator, Richard Matas. He had also translated Port Tropique which he had done a fairly good job on, but Sailor and Lula, as it is called there, wasn’t translated as well as it could have been and should be retranslated by Jean-Paul Gratias, which I think will eventually happen. It’s very difficult to gauge these things, so of course translators from all sorts of countries will write me letters asking for explanations of terms and definitions of words. I do my best to answer, and of course I’m glad some of them take the time to ask me, but boy, it’s a mystery, what is it in Japanese? What is it like in a language in which I have no expertise? That’s a tricky one.

80

NK: Jim Crumley said that in the first not-so-good translation of The Last Good Kiss into French (as The Drunken Dog), a ‘topless bar’ became ‘a bar without a roof’.

81

BG: That’s really great, I like that! That’s a good illustration of what I’m saying. But you’re really just happy that people are getting at least some of what you’re saying. I remember being told in Spain that Faulkner used not to be a very popular writer there. First of all Franco wouldn’t allow his books to be translated, so the translations were done in Argentina, and apparently not very well. And I’m sure Faulkner can be a bitch to translate. So he just wasn’t very highly thought of because, you know, he wasn’t a very good writer if that’s what he was writing! It wasn’t until years later, post-Franco, that the books were re-translated and Faulkner gained the recognition that he deserved.

82

But also there’s another thing about this. Some people’s writing just doesn’t work in another culture and language. I know some of my books work better in one culture/language than in others. For some reason I can’t get the French, who have so many of my books in translation, to publish the books of short stories. It’s very difficult to get the books of short stories published anywhere. They just don’t want short stories, they want novels and I think they’re missing a whole lot, because I came to the short story in a formal way, and then I fell in love with it. Often my short stories are concealed in the novels, there are many stories like that. But then I started writing just short stories and novellas, which is my favourite form.

83

NK: Why is the novella your favourite form?

84

BG: It’s just the right length, you can read it all in one sitting. I also love the fact that you can spend a week or a weekend with War and Peace, just go through it. People also love to have ‘beach reading’, they like long books and all. I hope the Sailor and Lula stories will be published in this country in one volume, one omnibus volume, I’m lobbying for that right now.

85

NK: Would that be like an Everyman edition, or a Library of America edition?

86

BG: Well you could talk to Geoffrey O’Brien to try to get me in Library of America. You should write him a letter! I would like to see all the Sailor and Lula stories and novellas get together in one volume like in Library of America. But in any case I hope all of those things are gathered together. Short stories in the US can get some real notoriety but they’re not best sellers. People like to sit down and have a sustained read, and I’ve lately fallen in love with the short story form.

87

NK: With both your practical-professional and analytic knowledge of US writing traditions and institutions across several decades, you would know far better than I the history of a diminishing number of magazine formats that once existed so abundantly for that short story form. They still do to some extent, the New Yorker, Harpers, the Atlantic Monthly, but nowhere near the same number.

88

BG: Right, there are very few venues in which to publish the short story. Most of them are academic, and then there’s the New Yorker, and that’s about it. There’s no longer the Saturday Evening Post, or Vanity Fair or Scribners, and the Atlantic Monthly just stopped publishing stories. When I started there were so many smaller magazines that would publish short stories; this market doesn’t exist now in the same way. And it was a way for people to actually make a living, writing short stories, so I can relate a little to that, and I published a lot of short stories in a lot of magazines, and a lot in Europe too. Also excerpts from novels.

89

NK: I always found it odd when English publishers would say that short stories are not greatly read and are hard to sell in sufficient numbers, yet you can see people in the London tube reading them on the journey from Tufnell Park to Clapham, or wherever.

90

BG: Well, I’m not a publisher, I don’t have the answer to that. I can only write what I write and put it out there, and hope that it’ll find the reading public. Some of the chapters in Memories from a Sinking Ship have been published as short stories but of course they’re a part of the whole, there’s a connecting tissue there, that’s why I publish them this way now, using and revising some of the material from The Phantom Father, which is published as a memoir, and Wyoming, as I talked about earlier, and a few from other places. And then a third of it is new work. So now I’ve got the whole thing, the whole canvas, but they can be read as short stories as well.

91

NK: In a couple of interviews I have conducted with some English publishers, Pete Ayrton at Serpent’s Tail Press, and Francois von Hurter at Bitter Lemon Press, I have floated the analogy that says if large publishers now conduct themselves on the model of Hollywood majors, with an emphasis on blockbuster titles and saturation release through the chains, do smaller/independent publishers function more like independent cinema (even allowing for the various changes and compromises that have attended that term over the last ten years or so)? What is your sense of the publishing scene in the US at the moment, from big houses to smaller, independent outfits?

92

BG: Publishing really changed in the 1980s when all of a sudden the big houses started thinking of themselves as movie producers or something, or being in a similar kind of entertainment business. Well, that’s not the business I came into. I was fortunate to start in this country with E.P. Dutton, a very old and revered publisher, the publisher of Joseph Conrad and A. A. Milne. I published my first novel, Landscape with Traveller, with them, and it was a different tradition then. I was very fortunate to start in the early 1970s and it’s changed a lot, I don’t think there is the same view of it as there used to be.

93

As always, some publishers are publishing wonderful stuff, others aren’t, I think a lot of good work being done is by smaller entities who have the opportunity now because so many writers have been dropped by big publishers because of lack of sales. These are so-called mid-list writers and I’m one of them, more or less, but my notoriety with the movies seems to carry over. My books sell much better in Europe than they do here. Whit Stillman, the director, lives in Paris now, and when I saw him in New York recently, he said, ‘you’re so famous in Europe, you’re only half that here, how come?’

94

NK: And I guess you said, ‘it’s not of my doing!’

95

BG: I said, you know, you go where you are liked and you hope you eventually get the recognition in your own country.

96

We started off this discussion by talking about fine presses, letter-press, and taking pride in that. Well, now, so many glitches occur because of this electronic processing. People just hit the wrong button and the whole thing is messed up. It’s very weird, it really is, I hate to sound like a troglodyte, a dinosaur, but it’s not so very long ago that people were setting books by hand, letter by letter.

97

NK: Hence the phrase, ‘mind your ps and qs’.

98

BG: Yes, and I’ve watched them do it. I was never a fine printer myself but I’ve always admired these people who seriously consider the font to use, what type will best suit the material? The history of the various fonts and so forth, that has always interested me.

99

NK: From favourite fonts to favourite sports. I see sitting on the piano behind me a baseball bat signed by Nellie Fox, a ‘Louisville slugger’; you mentioned that it’s an unusually shaped bat that you received as a gift. We haven’t yet discussed your long personal, lived and literary relation to sports.

100

BG: Nellie Fox used a ‘bottle bat,’ a bat with an unusually thick handle. I was always interested in sports. The only two things that ever really interested me in terms of thinking about a professional future were baseball and writing, that’s it. They were the only things that I ever seriously considered. I played all sports growing up, got to college and played baseball and my interest continues. When I lived in Rome I would go to the A. S. Roma soccer matches, so I’m still interested in sports. I boxed, I played baseball, football, basketball, everything that you could think of, and so did two of my sons, and my daughter was a great swimmer. I think it’s a very important part of life, if you can do it, if you’re able-bodied, mobile, it’s a great privilege. And to me it exists as a kind of meditation. Even today when I have a baseball game on television, it’s really like a meditation, there are periods of quiet and calm. I think that’s why I like baseball the most.

101

First, it’s a very subtle sport, it’s not for everybody. Babe Ruth, who was the great baseball player, once said, and he’s often quoted for the first half of this statement, ‘Baseball is the greatest game there is.’ But the second part of the statement was, ‘but you have to have grown up with it.’ And that’s really right, because then you can really understand it. Otherwise it’s just the home run and the strike out, just like with Australian Rules football and soccer, it would be the goal, but there are so many other subtleties, so many things that go into it, it’s hard to explain. And I think that there’s been such a literature built up around baseball, and boxing too, I think those are the two sports that have a whole literature built around them, and from them, and that’s a very interesting thing. And then there are certain notable exceptions like This Sporting Life, for example.

102

NK: The one Rugby League film!

103

BG: But it was a novel.

104

NK: Yes, by David Storey.

105

BG: And Alan Sillitoe wrote The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, so there are certainly great individual novels or films built around a sport, like This Sporting Life.

106

NK: That raises the issue of which good films can come from excellent novels related to particular sports, and also which sports can be plausibly represented on film. For example, it’s hard to think of a really good film with cricket at its centre, there’s something ‘unrepresentable’ about it.

107

BG: There was the film Jim Thorpe: All American (Michael Curtiz: 1951) but that was about the Olympic champion, Jim Thorpe, who was one of my great heroes as a child. Thorpe also played professional football and baseball. He was one of my great boyhood heroes, the greatest athlete in the world at the time. I even have a copy of The Jim Thorpe Story here, on that bookshelf.

108

NK: On my last visit here my friend Jim Kitses took me to a baseball game in the new stadium down there near the harbour, and I saw Barry Bonds hit two home runs. Great to see! Later I read all this stuff about drug taking in contemporary sport.

109

BG: So far as drug-taking in sports is concerned, all I can say is, people are always trying to get an edge, one way or another. People call it cheating but it’s just like earlier in baseball where various professional teams would station a spy in the centrefield stands or in the scoreboard or someplace to try to steal the catcher’s signs from the other team, all sorts of things like that. Recently there was a big piece about that and the Giants and the Dodgers and a very famous game in 1954.

110

But in any case, you’re always looking for an edge in sport. The fact that drugs came along in a particular time, well, back in the 1960s amphetamines were widely and freely used, certainly, by football players and baseball players. To get footballers out there to play, they shoot them full of bute or whatever, just like a racehorse, to get them out on the field. So, the step to steroids or human growth hormones was a very natural one, it’s part of our world. Then, after it’s happened, because it’s always this way, always after–then it has to be regulated or banned or whatever. Then the time comes. It’s like when I first came out here to San Francisco, it was right after LSD had been criminalized. It had been created as a tranquilizer but it was certainly one step beyond, so the government classified it as a narcotic , a dangerous drug.

111

NK: Well Kesey and others had done those experiments, some of which are touched on in Robert Stone’s recent memoir, Prime Green.

112

BG: As early as the late 50s and early 60s people were experimenting with LSD in various instances, sometimes academic, like Leary at Harvard, we know all this. The point is that, when you know what animal you’ve got, then you have to deal with it. It’s a similar thing with the use of drugs in sports, that’s all, and now they’re figuring out what to do with it. As for the use of human growth hormone or steroid use, in baseball and football teams, the owners of these teams aren’t concerned whether this is good or bad for you, that’s not their primary concern.

113

NK: What do you think of the practice of relocation of teams such that a New York based team, with all of that history, winds up on the west coast? What does that do to fans?

114

BG: The owners don’t give a shit about the fan, it’s all about money. What does the word ‘professional’ connote? It means you get paid for what you do. You have a professional sports team, well if you don’t get the fans coming out, or you think you can move to an area where it’s going to be more lucrative, they do it! They’re all carpetbaggers, that’s what’s going on, there’s no mystery in this.

115

NK: Well, you might have to follow the impact of the arrival of David Beckham into LA and US soccer, maybe the biggest thing since the moment of Pele and Franz Beckenbauer and the New York Cosmos.

116

BG: Well, when these guys are past it they come to America to collect! I’ve never followed soccer in the States but it should be bigger here than it is. When I was growing up, kids didn’t play soccer in the US. There were very, very few teams and now, in the last thirty years, kids growing up in the suburban culture play soccer, because there is room for it.

117

NK: In Australia there was a moment at which soccer was thought less likely to lead to a serious injury, compared with other winter sports such as AFL, Rugby Union and Rugby League, and so there was a kind of Mothers’ advocacy group for soccer.

118

BG: It’s funny, when I first went to London I played some cricket, I was asked to come by, as a baseball player, and I got the hang of it, and I enjoyed that a little bit. And then I did a term at Kings College in Cambridge, and I played on the American soccer team there. In fact our goalkeeper was Gene Siskel, of Siskel-Ebert, the TV movie critics. And I had a good time doing that but I didn’t really know how to play soccer so I related it to hockey, and that’s how I was able to think of it, visualise it and learn what to do. It was kind of like Babe Ruth saying you had to have grown up with it. I couldn’t ‘handle’ the ball, but I had to figure out what I could do so that I could contribute in some way? I had a good slapshot in ice hockey, even though I wasn’t a good skater. So you adapt, you figure out what you can contribute, and that’s interesting to me, figuring out what your value can be, how you can make the best use of your skills, that sort of stuff.

119

But the rugby guys, boy, I still think that’s the roughest game there is. I played a little in England. I was a running back and a quarterback in American football, but in rugby there isn’t any blocking! Boy, my admiration goes out to those guys, they’re tough. The University of California at Berkeley has dominated collegiate level rugby in America for years..

120

NK: Do you ever find it odd as you move between your fiction writing, done alone, apart from others, as you described your writing regimen earlier, and your movie writing which is collaborative and brings you into a much more public, heightened celebrity culture, not that literary culture doesn’t have its version of that as well.

121

BG: I don’t really court celebrity and in the movie business it’s really hard to avoid. Years ago I remember a producer saying, it’s time you hired a publicist, you’re doing work for Coppola, you’ve got a couple of books that have done very well, you’re living with a famous Italian movie star, you’ve got to get a publicist. And I said, Why? You already know everything! I thought it was an unseemly suggestion, but you walk a tightrope here, because you need to have a certain amount of publicity in order to have people pay attention to your work. For instance, submitting to interviews. Why are we sitting here doing this? Is it because people are really interested in how I write, what I write and what’s in my head or whatever? I guess people want to know what I’m thinking, and I should be properly flattered, but the truth is in the work. It’s all there, as B. Traven said.

122

NK: It’s good to see your essay on him open your recent collection, The Cavalry Charges.

123

BG: Now, he had an agenda, a reason for hiding or disguising himself, but he was also thirsting for attention and that showed in how he lived his life in Mexico City. Anyway it’s a really double-edged sword. You have to have a certain amount of exposure. But I’m a bit of a reluctant dragon. I guess I have been for a long time, for forever. I could have done a lot more but I’ve sort of discouraged it. I’m hopeful that the work will survive and that some of it will resonate, entertain and be appreciated, and my efforts haven’t been a waste of time and energy.

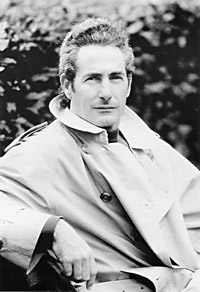

Barry Gifford

Barry Gifford’s novels have been translated into twenty-eight languages. His book Night People was awarded the Premio Brancati in Italy, and he has been the recipient of awards from PEN, the National Endowment for the Arts, the American Library Association, the Writers Guild of America, and the Christopher Isherwood Foundation. David Lynch’s film Wild at Heart, which was based on Gifford’s novel, won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1990, and his novel Perdita Durango was made into a feature film by Spanish director Alex de la Iglesia in 1997. Barry Gifford co-wrote with director David Lynch the film Lost Highway(1997); he also co-wrote with director Matt Dillon the film City of Ghosts(2003), as well as the libretto for Ichiro Nodaira’s opera, Madrugada(2005). Mr. Gifford’s books include The Phantom Father, named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year; Wyoming, named a Los Angeles Times Novel of the Year, and which has been adapted for the stage and film; The Sinaloa Story; The Rooster Trapped in the Reptile Room: A Barry Gifford Reader; Do the Blind Dream?; and The Stars Above Veracruz. His most recent books are The Cavalry Charges(essays), and Memories from a Sinking Ship(fiction). Mr. Gifford’s writings have appeared in Punch, Esquire, Rolling Stone, Sport, the New York Times, El Pais, El Universal, La Repubblica, Brick, Projections, La Nouvelle Revue Française and many other publications. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. For more information please visit http://www.BarryGifford.com

Noel King

Noel King teaches in the Department of Media at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. One current research interest of his concerns ‘Cultures of Independence’: a study of small and/or independent publishers in Australia, the UK, and the USA. His (relatively recent) interviews with the publishers at Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Scribe Press, Steerforth Press, Bitter Lemon Press and Serpent’s Tail Press have appeared in Westerly, Metro, Heat, and Critical Quarterly respectively. He also has an ongoing study of contemporary international crime fiction (in English) involving both English language works and translated works, a study of writers, publishers and critics in the UK and the US.