| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 40 printed pages long. It is copyright © Osama El-Dinasouri, Mohamed Metwalli, Ahmed Taha, Maged Zaher, Gretchen McCullough and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice. The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/egyptian-poets.shtml

|

[»] Ahmed Taha |

translated by Maged Zaher |

|

[»] Osama El-Dinasouri |

translated by Maged Zaher |

|

[»] Mohamed Metwalli |

translated by Gretchen McCullough and Mohamed Metwalli |

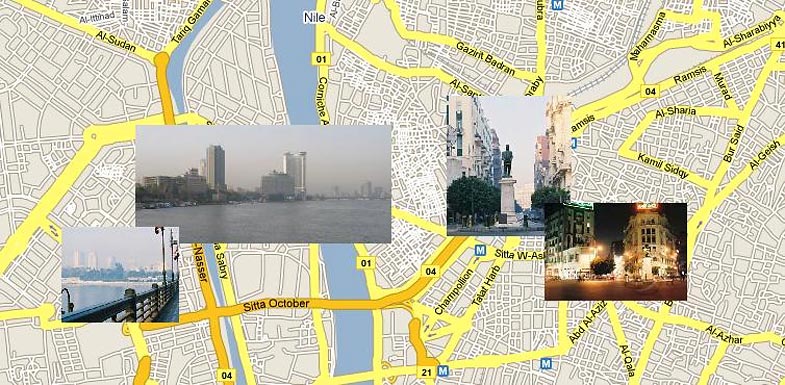

Cairo collage by Maged Zaher

by Maged Zaher

1

Arabic poetry originated like all other poetic traditions — as an oral art. Two thousand years later, innovative contemporary Arab poets are still working to transform the oral nature of their tradition, and its established rhetorical and formal devices, with their cultural implications of favoring passion over intellect, the masculine over the feminine, and patriarchy over subversion.

2

Art is inextricable from the political. At its inception among desert nomads and tribes, oral poetry was the most advanced media form, and poets had an important political role: they were the spokespersons of their tribes. Poetry then had to be easily memorable, which was accomplished formally via regular rhythm and rhyme schemes, and rhetorically via hyperbole.

3

Now — in the late twentieth and early twenty first century — the avant-garde Arab poets face different political and cultural tasks. They recognize the need for a multiplicity of voices, and for a balanced dialogue between passion and intellect. They also recognize the need to challenge both the patriarchal aspects of their lives including the political dictatorships, and celebrate both feminine and masculine voices on equal terms.

4

The generation of poets represented here claims that the current recognized icons of Arabic poetry — mainly the occasional short list candidates for Nobel prize: Mahmoud Darwish and Adonis — although admirable and ground breaking, haven’t fully broken free from this oral and patriarchal tradition. They also claim that this intense celebration of these figures to the exclusion of other poets, is in itself a symptom of the ills of the romantic, patriarchal aspect, they are set out to challenge.

5

Of course there were many attempts to break with the strict form throughout the history of Arabic poetry: In the 1920s and 1930s the romantic poets’ generation — e.g. the Apollo group in Egypt — tampered slightly with the strict form by using softer language, imagery, and multiple rhyme schemes in the same poem. However, the usage of regular rhythm and hyperbole were still intact.

6

In the late 1940s, the Free Verse Movement started using irregular rhythm and rhyme schemes, which was considered to be a major break with tradition. However this poetic revolution stopped short from doing away with rhythm and rhyme entirely, which made it essentially — although necessarily a major step on the path of modernizing Arabic poetry — a variation from within the oral tradition, in terms of both form and rhetorical devices.

7

The innovation of the Arabic poetry in Lebanon started in the late forties and early fifties with the works of Youssef El-Khal, Onsi El-Haj and others. Adonis and El-Khal magazine Shi’r made a lasting impact on the Arabic language poetics, and the poets it published, who abandoned both rhythm and rhyme altogether: El-Khal, Adonis, El-Maghout, and others, acted as a precursor to the work of the Lebanese poets of the seventies and eighties: Wadih Saadeh, Bassam Haggar, Abbas Beydoun, who acted in their own as precursors to the poets represented here.

8

The Egyptian poets of the nineties generation took the achievement of their Lebanese predecessors several steps forward, via 1 — employing plain and simple language. 2 — writing about the “non-poetic” details of everyday life. Effectively, the poet opted out of being a hero challenging the world (a la Darwish and Adonis) and — in the work of these poets — poetry didn’t just stop being an oral art, it also rid itself from hyperbole and heroism. An illustration of this would be Ahmed Taha’s important article: “From Reciting To Writing” published in the first issue of the underground influential magazine El-Garad “Locusts” co-edited by Mohamed Metwalli.

9

Some terminology issues:

In the Arab world, the term “Prose Poetry” is used to describe poems that do not use rhythm or rhyme, even if these poems have line breaks. This usage is different from what the Western poetic tradition recognizes as prose poetry. In effect the Arab poetics tradition’s “Prose Poetry” is more equivalent to the Western poetic tradition’s “Free Verse.”

Meanwhile. in the Arabic tradition the term free verse is used to describe poetry that has irregular rhythm and rhyme schemes. (Imagine poetry written in the iambic but every line has a different count, with arbitrary rhyme scheme)

10

In the Arab world a continuous gap between the spoken and written languages exists. The written language is formal while the spoken is not. An example of this would be — for an English language speaker — to use the standard everyday English language for speaking, yet old Shakespearian English for writing.

Political speeches are always rendered in the formal language. They depend — at large — on the same rhetorical devices of hyperbole and exaggeration used in classical Arabic poetry. Most poetry is written in the formal language. The nineties generation poets still used formal language but they somewhat modified their diction to match journalistic and everyday speech.

11

Breaking with the existing rhetoric is considered a sort of a heresy and challenge to the culturally — romantic/patriarchal/religious — accepted language, hence the major cultural tension that surrounds this form of poetry. The aesthetic debate was often peppered by accusations of the poets who broke with the tradition as agents of imperialism or communism.

12

The three poets chosen for translation here are emblematic of the thematic and linguistic changes mentioned in this introduction.

The poetry of Ahmed Taha, the oldest of the poets included here, is an example of the transition: the poet’s protagonist is still, largely, a tragic figure, yet not a heroic one like the ones you find in Darwish or Adonis’ poetry.

Osama El-Dinasouri, who died in 2007 from a kidney failure, pushed the envelope further: His poetry is a consistent attack on the sentimentalism of the old tradition. In contrast to Taha’s tragic protagonist, Osama’s protagonist doesn’t take himself seriously most of the time.

Mohamed Metwalli pushes things even more, his protagonist is almost the anti-hero, and is more interested in the surrounding objects and their existence than his own thoughts and ideas. One reason that his poetry might be controversial is that Egyptian poetry readers couldn’t relate his poems to the aesthetic boundaries of the two thousand year old oral tradition. His poems were occasionally accused that they sound as if they are translated and not originally written in Arabic.

13

There are more women poets writing and publishing in this group — e.g. Iman Mirsal, Fatima Kandeel, Nagatt Ali, Hoda Hussein — than all published Arab women poets in the whole twentieth century. I am currently translating some of their work, which I hope to get published in a subsequent volume.

From: The empire of walls (cantos and stories)

Hole

Because you are crowded behind my mirror:

one face that is shooting — calmly — its looks

like assassins shoot their bullets:

one

after

the

other

The bullet jumps:

one street after another

one year after another

on some night, it will penetrate the head

on another night, it will penetrate the heart

and on a third night, it will penetrate the genitals

This is why

I have to rest now

I have to build a wall after a wall

and kneel

behind my kingdom

as if I were the last emperor

Dec 31st

Egyptians wander like hippopotamuses

next to their tombs

they forget the cities behind the river

and they get closer

closer

They’re neither horses dashing off

in the middle of the desert

nor are they fish that open one door to the sea

and several doors to oblivion.

So why then, do you carry in this foreign land

a knapsack of ruins?

You bum around in the world

looking for a street that looks like “Shobra”

and coffee shops that look like the “Bostan”

you enter a tavern that you call “The Warehouse”

where you talk to porcelain bodies

and faces that look like tombs

covered with wax and colors

you talk with them in prose

your original features fade

The brown bartender asks you

you point far away to the “Opera” tavern

and lay your feet down and touch the base of the statue

you drink two shots with fava beans

capture the sparrow’s body between your canines

and hear it squeak

you think: how strange that all the world’s sparrows

land in the taverns of the “Opera” neighborhood!

who taught them this extreme politeness

such that, they step obediently between your teeth?

Was it the hoopoe — this old General in Solomon’s army —

who tricked them?

or was it a civilian president who fried them?

You can either get your 10th shot

or leave the tavern

and enter the forbidden zone...

Portrait of Anwar Kamel

You extend your spider web

beyond all exiles

and beyond the years that escaped you

this is why

the regime’s soldiers couldn’t hunt you

and your fragile threads remained

a dusky home for

the comrades who died or immigrated

How do you forget that you’re the one

who started departing

then invented your face

that we see so enigmatic

and the fingers that take refuge

in your eyes

whenever you hide

behind a stone table

or a silk coat

How do you hear now the beats of your body

whenever you read Nietzsche or Paul Eluard

you extend your hands to the desert

in order to meet God away from both the “Pasha” square

and the chairs of the “Odeon” café

you whisper to him about your rebellion

you remember your briefcase,

so you gesture to him

and give him the nearest poem, he reads it

and leans toward you

and the eyes smile

Portrait of George Henein

Because you write like a pirate

who is chasing after his letters

from one storm to another

a pirate who climbs his page

that is tattooed with skulls

and crammed with foreign slaves

and empty flasks

Because you scream whenever the shore

gets close to the ship

and you sigh whenever the bullets

play with your hair

as they move from one head to another

like music moves

You’re so sure then of life

and you hate it

you know what you’ll be after death

and you know that whenever you scream

your end will come

You leave your last lover

hug the violent water

and in your eyes:

piles of islands that you’ll never see,

battles that you haven’t fought,

bullets that won’t hurt you,

and the face of the home country you loved

your only home country

The wall of dream

All you have to do is to sit by yourself

with the minimum number of dreams

and without any money

to exhaust your heart that loves it

Just remember

before you start your daily path

that sex is not the only road

to revolution

however, it is the shortest one

and that women’s thighs are not the appropriate trenches

for class struggle

not because of their softness

or their flammable nature

but because they can’t contain a man

and his ammunition

of travel

and banners

and sedatives

So, the road has to be new,

carefully paved,

and on both of its sides, a line

of this type of woman

that puts your dreams on fire

it doesn’t matter which time it is

nor the color of their underwear

because you’ll keep going

holding dearly your old books

that you haven’t believed in yet

The wall of dream (2)

But I’m not

an isolated god

looking for an empty sky

and I am not deprived of coffee shops

or taverns either

also, I’m not incapable of love

I write lots of poetry about women:

It is just that I need a political party

to gather my organs

and give me an identification number

that I can memorize

or a dictator

who takes off his helmet whenever he sees me

and places a bullet in my heart

like grandfathers would place candy

in children’s palms

From: A final portrait of Anwar Kamel

Notes:

Anwar Kamel was an important member of the Egyptian avant-garde in the forties, a friend of George Henein and Edmond Jabes. Kamel was an early Trotskyite and wrote a book “El-ketab El-mamnoo’” that was banned then. After the military takeover in 1952, most of his friends either immigrated or were forced into exile. In the eighties, an old man, he published the new generation of Egyptian poets in his free, limited distribution, magazine/flyer “Fasilah”.

Shobra is a very crowded lower middle class neighborhood in Cairo where Ahmed grew up.

Anwar Kamel widens his exile:

For thirty years

you were alone in your exile

meanwhile, we crawled,

screamed,

and wore fatigues

You knew

that our path goes through here

so you were widening your exile

and building a fortress of names between your tomb

and the regime’s soldiers:

this is George Henein

taking out maps from his armpit

in order to pick where he would be born

and where he would get lost

this is Trotsky

bending over a book

and pointing to his heartache

this is Ramsis Younan

drawing a city of dreams and illusions

and disappearing in its streets

this is Besheer El-Sebaai

writing a romantic apology

for not dying in 1848

this is Ahmed Taha

creating these traps and holes

around himself

in order to chase his runaway childhood

this is Cairo, your city

not a single alphabet letter can penetrate it

to disclose its streets that host different epochs

like homeless old people

these streets where deities are conversing

as if they were friends in a coffee shop

and this is “Shobra”

a body that extends like a graveyard

that is big enough for everyone

yet doesn’t fit a single person

Shobra that is embarrassed of its sagging breasts

so it kneels

and the dead,

the hungry,

the kids,

and the grieving women

drop from it

like warm milk

yet the armies of police remain,

the empty cable cars remain,

the train graveyard in the north end of Shobra remains,

also the kids whose skin is mere dust,

men who mumble at night

and yell during the day,

women who weep — the same way they laugh —

beneath the weight of their husbands

or behind their coffins

women who get impregnated with men’s panting

and under their gowns their kids walk.

Story

Laughing so hard

you used to talk about your first death:

“I used to be a professional dead man

but I was about to laugh when I saw the

soldiers in their fatigues crying

like a bereft mother who lost her children

because El-Telmesani has escaped

also George Henein

and Ramsees Younan

I’m the last survivor.

For thirty years

I repeated my sermon

lest I forget it

I would climb the fences of Heliopolis

and watch you fight

while surrounded by the soldiers

and the Bedouins

who threw pots of perfectly-rhymed-sounds to you

while exchanging bullets

as if they were exchanging playing cards, hugs, or sex

no blood was shed

no veins erupted,

and no fetus was formed”

Anwar Kamel dies a natural death:

I always saw you

lying on the road

bullets gathered around you like flocks of flies

meanwhile your gray coat is completely open

and next to you, was this dark featherless bird

that — moments ago — used to be your leather briefcase

before they removed your papers from it

Yet you died an ordinary death

that is similar to your last escape

and similar to this awful type of death that we have in

Cairo,

Hegazz,

Nagd,

and Damascus

out of hunger

overeating,

laughter,

and depression

This canned death

that has already expired

and can only bring

vomit

and headache

this death that can be defeated by

aspirin and valium

You must feel jealous then of our surreal death

coming from the desert

riding its camouflaged camel

with computerized rockets in its saddlebag

and in the distance between its head and its fingers

a bowl of the leftover Fatta*

from yesterday’s dinner

________________

* Fatta is a Bedouin food

Anwar Kamel didn’t build a home country in his briefcase:

For thirty years

you were alone in your exile

and you were thinking

“Where does the original Cairo sleep

and how did the barracks extend to reach my window”

You were thinking

“How could the lost George Henein

have a home country

to put his arm around

or sit with in a café

and maybe feel its body after his second drink”

As for you

the home country that sits next to you doesn’t know your name

even after ten drinks

it may stretch

you may rub your eyes a little

then it would go about its daily journey

and you would go with your daily journey”

Well, let it be then

you only have this chest without nipples

after all the comrades have left forever

like wandering butterflies

where nipples grow like grass

on coffee shop tables

waiting for the dry lips

of those who migrated from the east

Let it be then

you will surrender your body to them

without any sign that points to your

specializing in death for thirty years

let them bury it in the graveyard of July

and you go back to what you were:

a spirit that wanders

in the relics of Heliopolis

A last dance with Anwar Kamel

As usual

I’ll slightly disagree with you

regarding who should die first:

Marx

or the husband of the woman I’m sleeping with?.

The General who is in khaki,

or the General who is in jeans?

Yet we will agree before the night ends

that everyone should die

and we will agree that we will organize everything

whenever the time permits

in the evening that follows

your final departure

Anwar Kamel celebrates the 14th of July:

Don’t say that all these defeats have colored me

with the color that doesn’t show in the darkness

this was my color from the beginning

as it is your color now

call it whatever you want

it is all you have

There is not a half death for you to die

and there is not half a color for me to live it

this is why I will stay — as I was created — a terrorist

and stuff my head with these big-bellied dying children

and ambush these blonde worms

like a fat spider

I won’t suck their viscous blood

I will organize them in my old notebooks

placed deep in each of their chests, a spear.

I will return their horns they put in museum halls

and their eyes that were stuck to the heads of fish

maybe I would dance around their corpses

that are lined up without shiny coffins

maybe I would fill their limbs with my words

that don’t know Rousseau or Voltaire

and don’t care about the 14th of July

and don’t resemble these three words

that fall from the pages of books

like fetuses in their third month

that stuck to the rears of cannons

like genital flees

But I embrace every moment with this shiny sword

that falls like an angry god

to put the heads of kings, prostitutes,

poetry recite-rs, revolutionary intellectuals,

Generals, beautiful women, and men of God in one basket

I wish if I were there

I would have brushed against the shoulders of these women

who are peeling their vegetables

then would have sat immediately behind that basket

wetting my quill with fresh blood

and write a love poem daily

on my sweetheart’s head

How did the gods ask about the tomb of Anwar Kamel:

There should be a dark universe

where the gods who created it stumble

while searching in the rubble of ancient cities

for any monument from the past

I’ll guide them like blind people

through the ruins that I know well

pointing at what remained of

steel,

plastic,

and canned sex organs

I’ll lie to them whenever I can

like tourist guides lie

to old folks seeking immortality

I will point at Paris’ skull and say:

here Anwar Kamel was born

and point to London’s vagina that is covered with gray hair:

here the faces of the revolutions of third world countries got stuck

and to Washington’s ass:

here third world countries’ officers became leaders

and to Moscow’s breasts that drip rotten milk:

here the leaders turned into philosophers

And when the gods try to return to their far skies

while holding their fake monuments

their eldest will ask me with his dignified voice:

what do you want you obedient servant?

I’ll kneel down in front of him

holding back a chuckle

and chant in a pious tone:

I want more flourishing cities,

more T.N.T.,

and more valium.

Anwar Kamel doesn’t intend to be a saint:

Now, here are the comrades: The Decembrists, the Octoberists

and the romantic assassin writers

unifying their death

they all arrive

with their unkempt beards dangling

with lit pipes.

They will fill the earth with saliva

the air with coughs,

and the sky with something dark

that resembles smoke

In between their sporadic exhalation

their teary voices will echo

while reciting the books of the ancestors

who followed God’s calling

so their blood flowed on His door

while carrying sharp-edged crosses

And you never return

Here are the comrades

raising the white flags

with bloody stripes

and the smallpox scars that resemble the stars

and chant the book of the Ecclesiastes

And you never return

Here are the comrades

their feet shaking absently

while they pray for exodus

the jazz music calms down,

the psalms begin,

their bodies are free from December’s ice

and they begin the New Testament

with their feet flying in the air

their beards touch in ecstasy

and moans that are louder than rock music

in front of the sacrifice scene

And you never return

Maybe you will write the last page

starting with a greeting

and ending with an apology

not for specializing in death for thirty years

and not for escaping from the time of the military and the Bedouins

and certainly not for migrating with the birds in the fall

but because — unlike these birds —

you won’t return the next spring.

The wall of passing

Carelessly

you throw your black hair

behind you

and unleash my dreams

What right do you have then

to lock these dreams at night beneath your bed

while you are awake

waiting for their death

I don’t have a lullaby about my past to tell you

so that you can sleep

and my dreams break free

All I remember

is that I was born like this:

a wolf who can’t even howl

yet it always dreams of prey

a General, who begs his victories

at the edges of coffee shops

with medals crowded on his chest

like an ant colony

Maybe I was an ancient general

when I shot my bullets at your chest

and maybe I was a professional thief

when I thought about what is under your short pants

but I want a real medal

and major battles

that could last for years

and be enough for the death of all other Generals,

the destruction of all cities,

and the defeat of all warriors

except me

Everything will be destroyed

except for this flabby house

where your undergarments are hanging

on its walls

and your thick shoes

lie in its corners

Only then

I’ll mash it with my hand to shape it like a plug

then hammer it on a forsaken sidewalk to mold it into a medal

I’ll make a flag of your bed sheet

that covers your bed and make it a flag

and then

I’ll hang the medal on my chest

the flag under my head

and sleep

From : One eye spaced out, one eye perplexed

Sentimentalism

You were supposed to die in my arms

wasn’t this what we agreed?

what should I do now

with the whole bottle of valium pills I had bought you

should I swallow them myself?

You changed so quickly

suddenly, you’re holding onto life

how astonishing: life!

isn’t it a dark depressing tunnel

and the endless journey

of suffering and confusion?

What should I do now

with the poem that I wrote for your elegy?

you ridiculed me

and I’ll never ever forgive you

Damn, what to do now

after I planned the future of my life

this life, that you destroyed with such a reckless move

I was about to start building

a stronger relationship with the flower shop

so it would give me the most beautiful flowers

at a reasonable price

so I could visit your grave

every week

carrying a beautiful gift

My heart pounds very hard now

whenever I pass by Salah-Salem street

and, overwhelmed with tenderness,

I find myself driving toward the “Basateen” neighborhood

where the family graveyard lies

Oh, and regarding the bars:

I found an old and quiet one

with high windows

and yellowish wooden walls

I would have gone to that bar every night

I decided on which corner table

I would spend the rest of my life

drinking, smoking, and crying

where young poets come

and point at me:

“Here is the recluse, sad sentimental guy.”

Oh, you coward,

you ruined everything.

Under the tree

My friends went to the sea

and left me alone

next to their clothes and shoes

My friends are crazy

they play so violently

they throw buckets of water

and piles of sand

at each other

however, deep down

they’re really kind-hearted.

I sit under the tree, read

and think about life and death

I’m the philosopher of the group:

the handicapped who loves everyone

and no one hates him

I’m the handicapped man who loved the handicapped woman

who was under a faraway tree

spinning around herself, her hair disordered

and white foam dribbles out of her mouth

without noticing me...

A Narcissist

The woman was

(no... the word woman isn’t the right one)

The girl was

(hmmm, not either)

The small woman was

Yes, this sounds right

The small woman that I loved

more accurately, the only woman that I loved

used to sit there alone merging with the night

starring at a deep clear well

she combed her short wet hair with her fingers

and kept on holding down her dark curls

one after the other

which led to the creation of small barren islands

that grew bigger and bigger

meanwhile the small black islands

in her head

started disappearing one at a time

My lover’s smooth and lovely head

Oh, my lover’s smooth and lovely head

I want to split you with an axe

oh, my small one

how did your tiny head

— through all these years —

contain this massive amount of hallucinations

listen to them: here they fly

like a defeated army of wasps

you can sleep now my love, sleep...

how pleasant is your smile

your eternal smile

with your whitened lips

and your empty gaze

that stare at an internal spot

so deep inside yourself

Memories

Instead of the boring and bloody

game of remembrance and nostalgia

from this night on

I’ll dream of you

Here it is coming from afar

the strutting wonderful shark

swimming determinedly and insistently towards me

Oh, no

it is not a shark, it is a sword fish

the water angry devil

with its pointed harpoon

oooh, here I am, my chest is penetrated again

fighting the waves on my back

and leaving a small stream of blood behind

The greedy sharks are gathering

to start their feast

Oh my God

even in dreams

the same memories

chase me!

Siblinghood

He said to her:

“Don’t worry

no love or desire

starting now we’re brother and sister,

meaning: “You’re as forbidden as my mother is.”

She said:

“Good.”

She sat silently for a moment and then said:

“Yeah, and it is not just about desire,

but also our siblings don’t usually like us.

— “They even sometimes hate us.”

— “Yeah you’re right,

but they help in hard times.”

— “Yes, but remember that sometimes

they are the only ones who harm us badly,

only them.”

Then he left

he looked as if he were learning to walk

and disappeared in the nearest corner

She sat there

Staring — baffled — at his footsteps

she didn’t really know

whether she was supposed to be happy or sad.

Deal

Would you let me have

a small area of your body

not more than one square inch

in exchange for you having

full control of my whole body?

No, I don’t mean anything dirty

I’m simply in love with your ass

this small aristocratic hill

that overlooks from afar

the large desert of your back

and all that I want

is to be able to kiss it whenever I see you

and to pet it more than once whenever we sit together.

In exchange, you will have the absolute right

to kiss or touch me wherever you desire.

Oh, what a beautiful pair of buttocks

and it looks like me

more accurately, it looks like

this deep down convex in my soul

that I can’t reach

May I ask you sister

does it hurt you

as much as mine hurts me?!

I badly need to write a poem

Not because the muse is haunting me

nor because I’m deeply in love with a woman

who doesn’t care about me

No...

simply I’m lonely

and because I’m shy

I don’t — usually — approach my friends first

(I used to have a friend

that I talked to whenever I wanted

but he is now abroad.)

However, whenever I write a new poem

I earn the right to drop by — unannounced — on any of them

even wake them up

without any feelings of embarrassment

actually, with enough joy

to make each of them sit for long hours

and share this joy with me

I’m not bad

I write the poems for my friends

— to be honest

I write them for myself —

I wrote once about dogs

not that I befriend dogs

— as you might think —

but because my friends are dogs.

Should I write then about my friends?

but even until now

there is a lot that I don’t know

about them

oh, I wish my friends were dogs.

Translated by: Gretchen McCullough and Mohamed Metwalli

A Sparrow Flew Over the Station Buffet

Usually two strangers

In the train station

Would talk about the changing weather.

The man mentions the cloud that once blocked

The train cars

and passengers had to get off

To push it aside.

(He remembers well a woman who refused to get off

And sought refuge in the bathroom.)

The woman mentions the herd of goats

Which blocked their way

Making her yell out of the window in the face of the deaf shepherd.

(She remembers well the conductor who was eying her thighs appreciatively

during the incident.)

And usually when the waiter whisks away the fragmented sentences

Heaping up commas and exclamation marks in the ashtray,

They leave.

In the background scene

A waterfall widens behind them

Sweeping away a sparrow

Whose death no one will remember.

— 1991

No Flowers in the House Today

The mother is haunted by continuous nightmares

Like hallucinations of wounded soldiers

And the father’s relentless snoring is

Weaving in and out of the nightmares

Bones; heaped on two single beds.

The children are grown and gone

Leaving behind, greeting cards

That need someone to dust them off

And be surprised at the ancient dates

And maybe hum a melodramatic song from the sixties.

This rolled-up poster of Chaplin

Might need someone to unroll it

To exchange a pure smile

With good-hearted Charlie

Who silently witnessed the fading of the children’s laughter

Between these muted walls.

In the past, the father recorded some of their laughter on reel tapes,

Basf brand,

And the mother stored the gadget

Under a chair in the living room

Hoping it would give birth to new voices

After the glimmer of the little elves has faded.

But no harm done!

Now they own a car, a video cassette to record

Whatever they please of children’s songs, a gadget to repel mosquitoes,

An Atari to kill boredom, a color television

To watch black and white movies and cry their eyes out.

They also have a lot of Kleenex to dry their tears.

On their phone, they recorded the number

Of a fast food restaurant,

Chatting with the delivery boy so long

Their meal would get cold

So they’d curse the bad food of the restaurant,

Hide underneath the blankets

With lit cigarettes in hands during their sleep

With no dreams at all.

No dreams at all!

— 1993

That’s How the Magician Pulls the Pigeon out of the Hat

Sex is over

The woman in front of the fireplace,

With a coffee cup trembling in her hand,

Begins to deliver her pious sermon

On the morals of noblemen

When they woo the women of the Middle Ages

While her eyes are fixed

On the icicles sliding down the glass of the window.

*********

Many trains have passed in the man’s head

Who stretches his feet toward the fireplace

To escape a bit from the Middle Ages.

He sees a woman who froze to death

One winter in front of the fountain

On a bench in a public square

While a pigeon

Kept pecking her hat for seeds.

(He stands next to her corpse

wondering about her history or her friends

But his wife leaves them and runs away, terrified.)

He wishes he could win her heart

And ask her about love

To detect the direction of her feelings

He wishes he could talk to her in front of the fireplace.

*********

The woman summons the realm of the noblemen so well

A wide, hoop skirt grows around her waist

And a giant chandelier of candles dangles from the ceiling

A soft waltz slowly envelopes the room

But the man disappears completely

She finds herself alone...

She places him on stage in the epilogue

Of a Greek tragedy

And hides in the audience,

He doesn’t know the lines

So he speaks of the fountain woman and her views on love,

And the hat, and the pigeon...

The noblemen laugh

She hates him with all her might

-Moving her eyes away from the window-

To sip her coffee which has begun to grow cold.

********’

Suddenly, they have sex again

But he wears a fashionable suit of a nobleman

And she looks like the woman from the public square

While the cold room is full of chandeliers, waltzes, a fountain,

Icicles, a hat, pigeons...and overwhelming happiness!

— 1995

Solitary Reaper

Wordsworth’s “Solitary Reaper”

And which, if I had been one of his Impressionistic contemporaries,

I would have replaced with a single red brushstroke

Amid a vague expanse of green dots

Turned shyly yellowish by a sun about to rise.

That reaper is sitting these days

-solitary still- with sharply defined features

Outlined by cosmetics — which has become mandatory at her age -

At a downtown café

With repressed sensuality

Kissing some young intellectual

Before excusing herself for a few moments and going to face the mirror in the Ladies’

To retouch her lipstick

That resembles the creamy wrinkled skin of light Turkish coffee,

It’s a crucial moment in her life

Reassuring herself of her beauty

Thinking up something to say to the young man outside

In defense of the opinions expressed in her new treatise

Emphasizing the generation gap from a class and economic perspective

And to feel more at ease during the expected conversation

She has pulled down her jeans to get rid of the remains of the beer

Sitting on the toilet with thighs which I don’t want to say are pitifully flabby,

So as not to seem callous —

It’s a crucial moment in my life too

Because I have always thought that the solitariness of Wordsworth’s reaper

Is rather different from my reaper’s

Didn’t the original reaper — come on, Wordsworth! — piss or shit in the field, for example,

Didn’t food get stuck in between her bright teeth, as usually happens to my reaper

During heated literary arguments over lunch with a young intellectual,

And didn’t her bare feet get stained with manure

To signify innocence and exuberance,

And was her sickle more or less different from my reaper’s cosmetic bag?

How she desired that middle-aged man,

With an immense moustache,

Whose face and clothes I have carefully chosen

To make him look younger and impressive.

He dashed into the bar suddenly,

As a bright idea lands like a dart into the heart of a boring novel.

And because she lives with her daughter — on their own of course —

In a building, also downtown

And because her daughter had entertained the same young intellectual

And they had become amicable enough to offend the reaper’s decency

After a few whiskies

She preferred to lie on her bed,

Leaving the window open, with a view of a crescent moon and a cloudy sky,

Waiting for the middle-aged man with the moustache to descend upon her,

Passing the time by impersonating the Solitary Reaper

Meanwhile, the daughter and the young man had polished off the bottle and started to think about getting rid of the mother’s inhibiting presence

How cruel, how monstrous and callous!

I say this pounding their chests with both fists

And looking at them with half-shut eyes

To tell the truth,

They have actually considered killing her

And dumping her bloodstained body

In the middle of some green field!

— 1996

Musical Kitchen

This may be the only musical kitchen in the building...

Here is a plump opera singer who loves food, especially goat meat, leaning against the stove. A goat thigh embedded with garlic cloves is in the oven. She’s singing parts of a modern opera written for her by her poet boyfriend — although this was not the age for poets to write famous operas — but the poet was patting a goat, tied up in a corner of the kitchen, whose turn had not yet come, before leaning on the other side of the stove and gazing appreciatively at his girlfriend’s long lashes, trembling, the pupils shrinking and enlarging as her passion for singing took over. The aroma of the meat created a sense of harmony in the room. It was the only hope in a future where artists sleep rough and starve. He placed the music sheets, he had just finished, on the wooden cutting board, with onions and vegetables, for her.

The cook — who was a loving mother to them both — opened the oven from time to time, inspiring hope in everyone’s heart; the singer would sing beautifully louder, and the poet’s writing would improve. If the goat panicked and tried to break free, the cook would bring her a couple of clover stalks in a beautiful bouquet. For it was everyone’s duty to calm the goat and create a pleasant ambiance for her. But the cook’s relationship with the goat was unequalled, even by the singer’s relationship with the poet...She even felt as though she was marinating slices of her own flesh while cooking every meal for them...She did not regret it, even if she became thin — as she was now — her bones protruding from her body...Art Above All.

The proof is that the two of them placed the roasted thigh on the table between them outside and busied themselves cutting it up, while the cook was sitting on a low stool in a corner of the kitchen feeling the purgation that follows a Christian self-sacrifice, soaking her apron with tears, while the goat — “the artist” — as the owners of the house used to call her — was gobbling the sheets of music and poetry with great appetite!

— 1997

Birds of a Feather

Birds of a Feather

Yesterday my guardian angel was walking beside me on a small wooden bridge connecting the two banks of the river

In such perfect step with me

That I thought I had fulfilled my duties to him, to Nature, or to God.

The water caught fire suddenly

And a billboard lit up on the other side of the river

Saying: Long-Lasting Angels at Unbeatable Prices!

I was content, so I didn’t look around

But I smelt roasting flesh

And burning feathers.

* * *

I’m a nice guy

But I’m obsessed with birds

I love them all,

Whether aristocratic such as the parakeets, colorful tropical birds and peacocks,

Middle-class like pigeons and doves,

Or objects of racial discrimination like crows and sparrows.

I throw them crumbs, cherries and blackberries

And call them by pet names and terms of endearment

Just as others do with women.

That’s why I never had a so-called ‘happy home’

So I left my family and roamed the land in search of birds

And I don’t think I’m a nerd or anything

When I get a fit — like the other day —

When I saw a dish of grilled quail at the restaurant next door

Surrounded by parsley, forks, knives, teeth

And similar atrocities!

* * *

I’m a nice guy too

But I’m obsessed with advertisements.

If I glimpse a billboard out of the corner of my eye on the highway, for instance,

I stop the car immediately to read the whole sign

Then go on

And if I hum a sad old tune

I catch myself singing an old commercial jingle;

Soap, matches, beer, toothpaste: it doesn’t matter.

Only yesterday I had hoped to get rid of this obsession

When I dreamed I was deep-kissing a woman I had desired for a long time

Under a gigantic neon sign at midnight.

From afar, we looked like two dark spots

Before an awe-inspiring monument

And the sign was burning up bit by bit.

* * *

My guardian angel was a few steps ahead of me

I felt there was a flaw in our relationship.

Perhaps my indifference didn’t appeal to him

Nor my mockery of ideologies, including love

He was a serious angel

And I was playing the fool as usual.

He spread his wings in wrath

And flew off the bridge.

At that moment I sprouted a jester’s cape, reddish skin and gaudy colors

And flew off trying to catch him.

I only got three meters up in the air

(But I loved it!)

Before falling in the water,

Which later, as you know,

Caught fire.

— 1998

Bordering Time

At the crossroads a man and a woman meet

And cling to each other,

Pretending it’s just the rain,

Under one umbrella.

While he imagines grass shooting up suddenly from the asphalt

She recites “The Road Less Traveled” to him.

At the flower shop the seller was fighting sleep

While a puppy licked in between his wounded toes.

The pub owner at the corner was dimming the lights

Taking off his apron and flapping it in the air.

A pair of wings sprouted from the bearded beggar

He hovered on top of the square clock

When it struck two a.m.

A raven swooped down to snatch a pair of spectacles from a British academic

While he was drying them under the light;

A raven’s gift to the beggar.

No one was watching the diva on the square screen

But a thirty-five-year old man

Who was convinced this was the most opportune moment

To commit suicide

As he sat on his suitcase.

At the edge of the countryside an exuberant poet

Embraced the fresh pastures

and was followed later by scores of immigrants

intending to sculpt a dream

at this late hour of the night.

There was a fat opera singer cradling a doll

She never gave birth to,

Addressing it with words of apology

As the notes jazzed up

Before tossing it, at the end of the scene,

Behind the set.

Yes, there was an emotional mayhem in the theater,

From which the man and the woman emerged

That’s why they resorted to outlandish fantasy

Under the umbrella:

They made an angel out of the beggar

And quickly deported him to the poetic countryside.

With their eyesight they moved all the sleeping flowers in the shop

And pasted them to the sidewalk.

Then they spoke with the suicidal man about the art of opera

When he was soaked by the rain,

Leaning against the glass of the flower shop

Next to a poster of the show.

They woke up the seller and scared away his puppy

As if they intended to buy a bouquet

But only bought a single dead rose.

The street cleaner swept away

Most of the passing conversations in the square.

What was left seeped through a hole in his shoes

What was left has sprouted in reality

Forming a plausible account of this moment,

Perhaps in the countryside,

At this late hour of the night!

— 2008

Osama El-Dinasouri

Osama El-Dinasouri was born in Mahelet Malek village in 1960, and died from kidney failure in 2007. He earned a bachelor degree in marine sciences from the University of Alexandria, and worked as a teacher. He published regularly in non-official magazines like El-Kitaba El-Okhra (The other writing) and El-Garad (The locust.) He published four books of poetry and a memoir “Kalbi El-harem, kalbi El-habib” (My old dog, my beloved dog.)

Mohamed Metwalli

Mohamed Metwalli was born in Cairo in 1970. He was awarded a B.A. in English Literature from Cairo University, Faculty of Arts in 1992. The same year, he won the Yussef el-Khal prize by Riyad el-Reyes Publishers in Lebanon for his poetry collection, Once Upon a Time. He co-founded an independent literary magazine, el-Garad in which his second volume of poems appeared, The Story the People Tell in the Harbor, 1998. He was selected to represent Egypt in the International Writers’ Program, at the University of Iowa in 1997. Later he was Poet-in-Residence at the University of Chicago in 1998. He compiled and co-edited an anthology of Modern Egypt Poetry, Angry Voices, published by the University of Arkansas press in 2002.

Ahmed Taha was born in Cairo in 1950. He earned a bachelor degree in finance from Cairo University. He founded and co-founded a number of literary magazines and groups: Aswat (Voices), El-Kitabah El-Sawda (The black writing), El-Garad (Locusts.) He introduced many writers in his magazines. He published three books of poetry, and many influential essays.

Gretchen McCullough

Gretchen McCullough was raised in Harlingen, Texas. After graduating from Brown University in 1984, she taught in Egypt, Turkey and Japan. She earned her M.F.A. from the University in Alabama and was awarded a Teaching Fulbright to Syria from 1997–1999. Stories and essays have appeared in: The Texas Review, The Alaska Quarterly Review, The Barcelona Review, Archipelago, National Public Radio, Storysouth and Storyglossia, among others. Currently, she teaches creative writing at the American University in Cairo.

Maged Zaher

Maged Zaher was born and raised in Cairo, Egypt and came to the U.S. to pursue a graduate degree in Engineering. His English poems have appeared in magazines such as “Columbia Poetry Review”, “Exquisite Corpse”, “Jacket”, “New American Writing”, “Tinfish”, and others. He performed his poems at Subtext, Kootenay School of Writing, Bumbershoot, St. Mark’s Poetry Project, Evergreen State College, and other places.