| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 17 printed pages long. It is copyright © Art Beck and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice. The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/beck-rilke-torso.shtml

paragraph 1

At the 1999 ALTA conference in New York City, Rainer Schulte commented (something along the lines of) that, despite dozens of versions, Americans continue to re-translate Rilke and would probably keep on doing so until “we finally get it right.” 1999 was also the year that William Gass’ Reading Rilke appeared. For those who haven’t read that book — it contains not only Gass’ translations of the Duino Elegies, but extensive discussion on and comparative translations of a number of other Rilke poems. The cumulative result seems to be a compendium of voices that, taken together, might be thought to approximate and recreate Rilke’s voice in English.

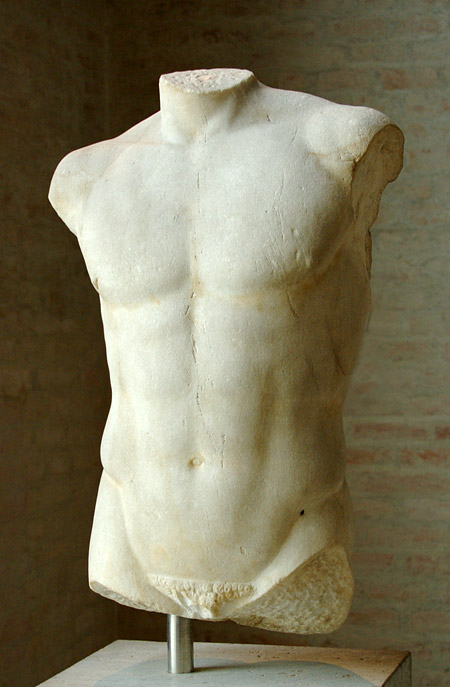

Torso of Apollo. Copy, probably after a statue of Onatas from Aegina (ca. 460 BC). Artist/Maker: Unknown (original by Onatas?) Dimensions 76.5cm Accession number Inv. 265 Location Glyptothek, Munich, Room 3 (Saal des Diomedes) Photographer/source User:Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2007-02-08. Released into the Public Domain. Image Source: Wikipedia at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

Image:Torso_Apollo_Glyptothek_Munich_265.jpg

2

Gass’ book seemed almost universally well received and reviewed. The only (partial) dissent I’ve come across is an essay by Marjorie Perloff — Reading Gass Reading Rilke, originally published in Parnassus but now readily available on the internet.

3

While Perloff gives Gass full credit for his critical acuity , she also notes — as a native speaker — the “clunkiness” of Gass’ translation choices (and of many of the comparative translation quotes). I’m wary of oversimplifying a nuanced and informative essay that rewards a full reading. But at least as I read her, Perloff might be characterized as saying that, while Gass’ critical and biographical insights are often wonderful — the actual translations seem to fail to capture the unique and subtle combination of modernism, animism and poetic abstraction that Gass’ critique so aptly describes. She also notes — as other native speakers do — that for all his complexity, Rilke’s German voice in the Elegies remains conversational and contemporary. As opposed to the highly mannered, “high poetic” tone of many of the translations.

II: High Poetics

4

As a native English speaker my own observation is that I’m struck by how commonplace it is for Rilke translators to comment on Rilke’s “lack of a sense of humor”. And that most of the same translators also seem unwilling to be open to any ironic interpretations in Rilke. For these translators, high poetics will consistently trump irony. I think Gass exemplifies this approach in a chapter entitled Ein Gott Vermags that discusses translating the First Duino Elegy. He compares fourteen versions of the poem’s opening lines:

5

Wer, wenn ich schrie, hörte mich denn aus der Engel

Ordnungen? Und gesetzt selbst, es nähme

einer mich plötzlich ans Herz: ich verginge von seinem

stärken Dasein, Denn das Schöne ist nichts

als des Schrecklichen Anfang, den wir noch grade ertragen,

und wir bewundern es so, weil es gelassen verschmäht,

und zu zerstören. Ein jeder Engel ist schrecklich.

6

Gass finds most insufficiently poetic for various reasons, but manages to stitch together his version with the help of the other versions:

7

Who, if I cried, would hear me among the Dominions

of Angels? And if one of them suddenly

held me against his heart, I would fade in the grip

of that completer existence — beauty we can barely

endure, because it is nothing but terror’s herald;

and we worship it so because it serenely disdains

to destroy us. Every Angel is awesome.

8

To translate these opening lines is admittedly a serious task. They’re as famous as the opening of The Waste Land. In fact, I think there are many parallels between the First Elegy (which was written in 1912) and Eliot’s The Waste Land, published ten years later. For one, the theme of facing existential issues without being able to access the traditional comforts which lie in ruins. Writing from a crack in the order of things. Eliot’s poem is set in the aftermath of WWI, Rilke’s, almost eerily, foreshadows that cataclysm. Beginning with a sense of vague foreboding and weighing and discarding one explanation after another until the Elegy settles on what’s arguably its central image: “those dead youths” “taken before their time.” Their very names “tossed aside like broken toys”.

9

And, for me, another similarity is the sense of barely controlled neurosis that The Waste Land subtly begins to assume as it slips into the voice of the Countess Marie. Somewhere around the tenth line, The Waste Land’s meter begins to take on a nervous heartbeat.

10

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the archduke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

11

I get this same sense at the beginning (but not the end) of the Elegy. The initial images may be exalting for some, but they could also be discussion points for an analyst’s session. The “cunning animals” who “notice the world’s a language in which we’re not always quite at home”. “Night, when the wind full of outer space feeds on our faces.” For me, the schrie isn’t a “cry” or a “call”, but something closer to the Edvard Munch Scream. And to my ear, Gass’s version of these lines reads, not as particularly poetic, but as something like Cliff notes for readers with a 19th century aesthetic trying to digest a modernist poem. Rilke translated by Wordsworth.

12

Gass seems particularly disdainful of the conversational tone of David Young’s version:

13

If I cried out

who would hear me up there

among the angelic orders?

And suppose one suddenly

took me to his heart.

I would shrivel

I couldn’t survive

next to his

greater existence.

Beauty is only the first touch of terror we

can still bear and it awes us so much

because it so coolly disdains to destroy us.

Every single angel is terrible.

14

I’ve always liked Young’s version, and I’d be tempted to take that wry intimate voice farther in English, even bordering on idiom:

15

Then even if I shrieked to high heaven, who’d listen

to me there among the angelic orders? And

suppose one of them did swoop me to heart:

I’d die, seared by exposure to that stark, concentrated

being. Because beauty’s nothing, the mere beginning

of a panic we’re still just barely able to contain.

And we continually praise it, hoping it continues

to disdainfully refrain from obliterating us.

Every one of the angels is terrifying.

III. Workshopping

16

As someone who’s been translating Rilke on and off for years, my own reaction on reading Gass was :”Well that’s it! The last nail in the coffin.” Gass seemed to present such a comprehensive picture of what’s out there — the agreed upon, standard Rilke, as it were — that Rilke’s English voice seemed gelled for our time. It seemed to me, after reading Gass and his reviewers, that it was going to take another generation before anyone might be open to anything significantly different.

17

But why do I think the “standard” Rilke voice — that seems to be shared by most of the ubiquitous versions — needs a new generation of translators? I’ve always felt that Rilke stands with one foot in the 19th century with the other firmly planted in 21st. I’ve sometimes thought of him, especially in the Elegies, as the poetic leg of a three-legged stool — the other two legs being Einstein and Freud/Jung. To my mind, the current trend in translating these essentially modern — maybe even still emergent — poems is that translators seem to be insistent on falling back into the 19th century rather than to where Rilke’s unique aesthetic is leading us. Or maybe more appropriately — where that aesthetic might lead us after taking on a second life in English. Because insofar as poetic translation is poetry — it’s an exploration of the target rather than the source language.

18

I began translating Rike in the ‘70s. At the time Rilke wasn’t the icon in America he’s since become. ( Did Rilke’s “American — Idolization” begin somewhere in the ‘80s when, in the deal of the century, we seem to have traded Bukowski to Germany for Rilke?)

19

The translations I was aware were Herter Norton’s and MacIntyre’s and a few others dating from the ’30s and ’40s. But this was also the time that David Young’s iconoclastic translations of the Duino Elegies began coming out in Field. They spoke in an immediate, contemporary English voice. I’ve often felt that the open form of the Elegies makes their poetry more, not less, difficult to capture. Young recast the Elegies in William Carlos Williams-like triplets that seemed to energize and focus the rambling poems. This was a poet I didn’t recognize in Norton or Mac Intyre. So I started playing with translating Rilke on my own. Above all. I wanted to hang onto that “21st century leg.”

20

Robert Bly was also publishing his highly personalized Rilke versions and though some of these have been since maligned, many have an energy and stand on their own as poems in English. Qualities also shared by Lowell’s very loose “imitations”. These are qualities, I think, often lacking in the trend that started with the “more accurate” Mitchell.

21

The scope of Stephen Mitchell’s contribution — both in interpreting and popularizing Rilke is unquestioned. But since Mitchell the trend, to me at least, seems to involve less an internalization and re-rendering of the original text, than a re-translation of existing translations. With Gass’ — in some cases, blatantly patchwork versions — representing a kind of translation by committee culmination.

22

It’s as if Rilke (or Mitchell) has been work shopped. To my taste, so many of the recent versions seem akin to the “translation” of German craft beer into Budweiser. Or of terroir driven wine traditions into the Mondovino international style. The current translations are popular, accessible, and retain an underlying Rilke spirit that can still at times intoxicate.

23

But for the most part, at least for me, they fall short of that rare but essential poetic translation quality:. The ability to be read as if they were originally written in the target language. They remain, not poems, but representations of poems. Above all they seem to lack the element of risk that — like flight — poetic translation demands.

IV: An aesthetic question

24

So, at the risk of setting myself up for a great pratfall — Let me try to demonstrate some of what I think is lacking. Archaic Torso of Apollo is a ubiquitously translated chestnut that I think provides a good forum for the kind of dialogue that might be productive.

25

Archaischer Torso Apollos

Wir kannten nicht sein unerhörtes Haupt,

darin die Augenäpfelreiften. Aber

sein Torso glüht noch wie ein Kandelaber,

in dem sein Schauen, nur zurückgeschraubt,

sich hält und glänzt. Sonst könnte nicht der Bug

der Brust dich blenden, und im leisen Drehen

der Lenden könnte nicht ein Lächeln gehen

zu jener Mitte, die die Zeugung trug.

Sonst stünde dieser Stein enstellt und kurz

unter der Schultern durchsichtigem Sturz

und flimmerte nicht so wie Raubtierfelle;

und bräche nicht aus allen seinen Rändern

aus wie ein Stern: denn da ist keine Stelle,

die dich nicht sieht. Du mußt dein Leben ändern.

26

What follows is my own most recent version. Maybe, the twentieth revision in as many years and almost certainly not the final version.

27

Rilke: Archaic Torso of Apollo

We didn’t understand that outrageous head, the eyes

whose irises actually flowered. But his torso

still stares like a chandelier turned low,

dimmed to illuminate just its own steady

flame. Why else would the crease

of the chest muscles blind you? And the slight

tensing of the loin — it’s nothing if not a smile

traveling to his center on a journey to procreation.

If not, this would only be a fragment

of mutilated stone under the shoulders’ transparent

slump. Wouldn’t glisten, anymore than a predator’s

fur, or leap like radiating star fire.

Because there isn’t any single part of it that isn’t

watching you. You have to live another life.

— Trans. Art Beck 2007

The Legendary Outrageous Head wherein the Eyeballs Rolled

28

My fear of a pratfall is triggered from line one here. Let me preface with the admission that I have very limited confidence in my entry level German. But that I do rely heavily on my own sense of what constitutes the “poetic” and on my own, perhaps quirky, sense of Rilke’s aesthetic. Querying native speakers is always invaluable, but Rilke’s multi level images seem to lead even the German reader to the realm of questions that belie final answers.

29

So what makes me so brash as to diverge from almost every American translator’s reading of the first sentence?

30

Wir kannten nicht sein unerhörtes Haupt,

darin die Augenäpfel reiften.

31

In her 1938 volume, Mrs. Norton translated the lines as follows:

32

We did not know his legendary head,

in which the eyeballs ripened.

33

Mitchell, in what’s arguably the “standard” contemporary collection, in 1984:

34

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit.

35

Snow’s 1987 version:

36

We never knew his head and all the light

that ripened in his fabled eyes.

37

And Gass, in 1999.

38

Never will we know his legendary head

where the eye’s apples slowly ripened.

39

Rilke refers to the statue’s missing head as “unerhörtes”. I’ve yet to find a German dictionary (or native speaker) that doesn’t define “unerhörtes” as some variant of “outrageous”, generally with a negative implication. The word literally means “unheard of”, but can also be applied to a “fabulous price.” Mrs. Norton notes that she moved it along from “fabulous” to “legendary”. I don’t want to pick on her, because as can be seen above, nearly everyone seems to have followed her lead. Her German was probably better than mine and she was closer to Rilke’s time — she may well be right.

40

But , there are aesthetic consequences. Augenäpfel is literally German for “eyeballs”. In choosing between “outrageous” or “legendary” for unerhörtes, you have to ask whether Rilke meant the next phrase “augenäpfel reiften”(“eye-apples ripened”) to be a gently eye-ball rolling pun or a serious poetic image.

41

Because that interpretative choice — coming as it does in the very first line — effectively moves the poem either forward or backward in time. Is this 1908 poem an early modernist poem — a New Poem — or a piece that begins by invoking a 19th century nostalgia?

42

In a 2007 New Yorker article, Milan Kundera returns to a favorite subject — ‘kitsch”. A word, he says, which “describes the syrupy dregs of the great Romantic period.” He goes on to say that “Kitsch long ago became a very precise concept in Central Europe, where it represents the supreme aesthetic evil.” His references are somewhat later than 1908, when Archaic Torso was published — but it’s hard for me to accept that Rilke — a contemporary of Kafka and Kockoschka, a late Austrian Empire sophisticate and an emerging modernist would, at this stage in his career, treat augenäpfel reiften as a totally serious image. Doesn’t unerhörtes, when literally translated, reinforce this? And doesn’t stretching the standard context of unerhörtes into “fabled” or “legendary” — into something positive rather than negative or suspect — just add to the kitsch?

V. Back to the Future?

43

If we back away a bit and put Archaic Torso into its publication context, maybe the translation choice can be clarified. Archaic Torso is the first piece in the second volume (or as titled “Another Part”) of New Poems. The first volume, released in 1907 begins with another Apollo poem. Früher Apollo (Early — or childhood — Apollo). That poem begins:

44

Wie manches mal durch das noch unbelaubte

Gerzweig ein Morgen durchseit, der schon

ganz im Frühling ist, so ist in seinem Haupte

nichts was verhindern könnte, daß der Glanz

aller Gedichte uns fast tödlich träf:

denn noch kein Schatten ist ein seinem Schaun,

45

Roughly:

46

The same way once in a while through the still

bare branches a morning glares through that’s already

entirely spring; that’s the way there’s nothing

in his head to prevent it: The brilliance

of all poems from searing us almost fatally.

Because there’s nothing to shade us from his stare.

47

The poem goes on to say that “only later” would the child Apollo’s eyebrows sprout up into a tall rose garden from which the petals would drop “into his trembling mouth...” as if his songs were being instilled in him. Quite an “outrageous” head.

48

Snow, in his preface to “New Poems, 1908. The Other Part”, compares the two Apollo “frontispiece” poems. And quotes Rilke’s letter to his publisher which expressed the hope that the second volume could chart a somewhat parallel course with the first, but “only somewhat higher, and at a greater depth and with more distance.” If so, might Rilke — in beginning New Poems, Another Part — be saying: “This is where we came from but not where we’re going”. It may be clear poetic logic for the Apollo frontispiece of the second volume to begin by distinguishing itself from the first Apollo with a wry pun. But beyond that the dismissive unerhörtes allows Rilke to have it both ways — to both acknowledge and incorporate the pun as an essential element of the poem.

49

My own (still somewhat clumsy) choice for the first sentence of Archaic Torso would be something like: We didn’t understand that outrageous head, those eyes whose irises actually flowered. But in any case, I don’t think Archaic Torso should be translated without keeping Früher Apollo in mind as a touchstone. So much has been written in English about what Archaic Torso “means”, but very little about what it “says”. Referencing Früher Apollo helps ground us from endless philosophizing.

VI: The Candelabrum

50

While unerhörtes in the first sentence has been treated fairly uniformly by most translators, Kandelaber in the second sentence has been a subject of some controversy. Gass in his commentary on this poem summarizes the discourse. He notes that Herter Norton interprets the second sentence as: But his torso still glows like a candelabrum in which his gaze, only turned low, holds and gleams.

51

But Leishman, another early Rilke translator, said that Kandelaber was, at the time, colloquial for a gas street lamp. Leishman’s translation reads: ...his torso like a branching street lamp’s glowing wherein his gaze, only turned down, can shed light still.

52

Gass expands on the street lamp image: Yet his torso glows as if his looks were set above in it in suspended globes that shed a street’s light down.

53

The difficulty here. I think, is the compound word zurückgeschraubt, literally “back screwed” or screwed down. A mechanical word that doesn’t seem to appropriately modify either candlelight or a gaze. But the problem with the streetlamp image is twofold. For one thing, gas streetlamps are either lit or unlit — all the way on or all the way off.

54

Secondly, the streetlamp image seems to come from somewhere outside the poem, somewhere more Cocteau surreal than Rilkean. What’s a streetlamp doing in a museum, and why is Apollo lounging against it?

55

This sentence seems to give everyone fits. I think both Mitchell and Willis Barnstone (in a fairly newly published translation) seem to do as well anyone in making sense of it:

56

Mitchell: And yet his torso is still suffused with brilliance from inside, like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low, gleams in all its power.

57

Barnstone: Yet his torso still glows like a candelabra turned low in which his inner gaze is never dead and gleams with power.

58

But the image still seems blurred, wordy and somehow a “reach”. How do you turn a candelabra low? And Mitchell’s image evokes an oil or kerosene lamp, not a multi-flamed candelabra. He makes up for the diminished flame by interjecting in all its power. And is it a sign of how “standard” Mitchell’s 1980’s versions have become that Barnstone also interjects power ?

59

When I first tried to translate Archaic Torso in the ‘70s, I had similar problems understanding the image and simply chose to slough it off with an imagined spin: But his torso still glows as if it were a candelabrum held out — tentative and brilliant — in front of himself to light the way.

60

I can only attempt to pardon myself by noting that my own spin was probably no more fanciful than Gass’ or Leishman’s. But by the time I revisited the poem in the late ‘90s, I was lucky enough to have come across a tattered Rilke contemporary Hachette German-English dictionary at a garage sale. Lo and behold, unlike most current dictionaries, that circa 1910 dictionary contains only one definition for Kandelaber — chandelier!

61

So Leishman was at least half right. This poem dates, not from the era of candlelight and oil lamps, but from the end of the gaslight era. When even the first electric chandeliers were produced with alternate gas jets to hedge the emerging technology bet.

62

And the regulating screw of the gas chandelier preceded its modern counterpart, the dimmer switch. There are antique “candelabra chandeliers” for sale on the internet, and my sense is that, at least in English candelabra and chandelier, were probably more or less interchangeable until the language chose chandelier for electric fixtures and (as in German) relegated candelabra to candle light.

63

My own current version is:

64

...But his torso

still stares like a chandelier turned low,

dimmed to illuminate just its own steady/flame...

65

You could legitimately question whether “stare” is too strong a word for Schauen ( a noun in the original). But looking at this poem in tandem with Früher Apollo, “stare” is certainly not too strong for the word Schaun in the line quoted above: denn noch kein Schatten ist ein seinem Schaun. A look containing the brilliance of all poems, and capable of fatally searing us.

VII: The decapitated god

66

Now, I have to beg forbearance if I edge into the territory of what the poem “means” as opposed to what it “says”. My intent isn’t philosophical, but aesthetic — to explore the emotional tone of the images.

67

The New Poems include four on the theme of Christ’s crucifixion. In the 1907 volume, The Garden of Olives and the wonderful Pieta (in which Magdalene rather than the Blessed Mother cradles Christ’s body and laments the sex they never had). These are paralleled in the 1908 “Another Part” by the starkly naturalistic, almost clinical Crucifixion, followed by The Arisen in which Magdalene confronts her still quite complicated would be lover’s feelings for the resurrected Christ.

68

I may be reading too much into Archaic Torso (if too much is ever possible in this piece) — but as I get to the second stanza a mental image of the Apollonian equivalent of a church altar crucifix begins to form. Why is Apollo’s head missing?

69

Whether deliberately decapitated or just neglected, the god has been desecrated and sacrificed. The stone is inhabited, alive with meaning and almost every one of the lines could be applied to the way a believer might view a figure of the crucified Christ. (As a parallel, the child Apollo in Früher Apollo might as easily evoke the Christ Child).

70

The “procreative smile” might seem blasphemous or sadistic in a crucifixion scene — but Baudelaire or Rimbaud wouldn’t flinch — and — what makes this Apollonian instead of Christian is that we have the semen-smile in place of redemptive blood. (As an aside, there’s also a smile in the last stanza of Früher Apollo: und nur mit seinem Lächeln etwas trinkend. ...”and only with his smile does he drink these things...”).

71

But to get back to the point: Just as the torso’s powerful Schauen in the second sentence flows from the tricky Augenapfel in the first line, the failure to acknowledge divinity with which the poem opens echoes its consequences in the mutilated stone (enstellt und kurz).

72

In fact the opening words ,Wir kannten nicht, translated in their German word order — are We knew not... evocative of the biblical “Father forgive them for they know not what they do.”

73

This is another reason I find myself departing from the same kind of easy romanticism that delights in fabled ripening eye apples. The New Poems, especially the 1908 volume. contain a plethora of starkly etched images and pieces like “Corpse Washing” and “The Beggars”. Archaic Torso, for all its animism, seems no less stark.

74

At the risk of belaboring the impact of that small opening adjective, if we briefly return to unerhörtes in the first line, it’s interesting to note that my early 20th century Hachette also includes in its definitions of that word an official dismissive: “refused, not granted.” Adding another layer of meaning to the dismissed head — and the rejected god we didn’t understand.

75

But when you start off with a “legendary” head, one can understand how a translator might find it appropriate to poeticize Apollo’s shoulders in dieser Stein enstellt und kurz unter den Schultern durchsichtigem Sturz...

76

As Norton did: Else would this stone be standing maimed and short under the shoulders’ translucent plunge.

77

Or as Mitchell, in expanding on her lead says: Otherwise this stone would seem defaced beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders..

78

Not to mention Gass’: Otherwise this stone would not be so complete from its shoulder showering body into absent feet.

79

Somehow, although he reaches pretty far for the sake of a rhyme (“knife” to go with “life” in the sonnet’s final line) Willis Barnstone I think presents an image more consistent with the headless god: Without that light this stone would have no face, its falling shoulders crack loose with knife..

80

Perhaps, I’m too drawn to a more conversational voice here, but I find what seems an un-embellished translation of Schultern durchsictigen Sturz into where it seems to want to go in roughly idiomatic English is sufficient in itself: i.e. the “shoulders’ transparent slump.”

81

The god, after all, has been rejected, (not to mention decapitated). How did the translucent waterfalls get in here? An image that seems to have no connection with either the stone or the inhabitant god.

82

It’s worth noting that Snow, departing from the “cascade” reads the line as “shoulders’ invisible plunge”. An abstract image that, while triggering the question: “What’s an invisible plunge?” — at least points to an invisible inhabitant.

VIII: Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright

83

For me the poem’s most difficult images are the ones that follow the slumping shoulders: und flimmerte nicht so wie Raubtierfelle;/ und bräche nicht aus allen Rändern/ aus wie ein Stern...

84

Literally “and not glitter the way a predator’s fur, and not break out from every boundary the way a star...”

85

Is there an implied double negative here? Raubtier is the only generalized or abstract noun in the poem. A class of beasts rather than a particular animal. (The Raubtierhaus in the zoo, like the “Lion House” holds a variety of big cats.) And Stern, here, also seems to have as much to do with the concept of stars as with any particular star.

86

What nags at me, attempting to translate these lines, is that predators’ coats don’t glitter, they’re camouflaged. They generally blend with the landscape. Night hunting cats slink in the shadows. It’s only in poetry that tigers burn bright in the night. Similarly, bursting stars are a rarity. The power of a star is generally self contained. And even if one broods on black holes and light years, an actual star burst is a remote, cool and silent omen. Having no discernable connection with ferocious animals.

87

When I first attempted this poem in the 1970s, I presumed way too much liberty and recklessly recast the lines as: and shed no more light than the coats of night hunting beasts, couldn’t break out of itself anymore than the power of a star from its gravity.

88

When I returned to the Torso, twenty years later, I decided this was far too much spin. After all, a big cat in the mind’s eye can glitter the way, say, a roll of fifty dollar bills “glitters” or a cartoon fire cracker “shimmers”. And if Rilke’s Panther were ever to break free of its cage, might it not be like an exploding star?

89

But I’m still not happy with my current version: Wouldn’t glisten, anymore than a predator’s fur, or leap like radiating star fire.

90

I sense I’m not catching some very simple possibility that might retain the sense of both abstraction and compressed dangerous energy these lines seem to have in German. But which seems to dissipate in most English versions.

IX: Another Life

91

The poem’s last line, Du mußt dein Leben ändern, has probably generated as much philosophic commentary as any line in 20th century poetry. Perhaps because, at least in English translation, it seems to come from nowhere. A tiger’s leap of a conclusion: “You have to change your life.”

92

A simple, conversational statement, but readers, translators and commentators seem to agree it means something deeper than “You need a new job” or “It’s time for divorce.” Interpretations abound and it would be nice to have fifty dollars for every academic essay and term paper written about this line.

93

Almost all translators have recognized the need to read more weight into the line than “you need a change” and most have reinforced this by using “must change” rather than the conversational “have to — or need to — change”. But no one — at least no contemporary poet — would say “You must change” in current American usage. Using “must” interjects at best an Anglicized voice — but also to American ears — a consciously Victorian tone. Rather than an insistent inner whisper in a museum — must imparts a proclamation in an artificial voice.

94

Yet even the literal, conversational: You have to change your life startles the reader and sends critical commentators into the realms of uncharted metaphysics.

95

But what if the line doesn’t quite come out of nowhere? Maybe it would be helpful to think about this line, not just “philosophically” but like a poet publishing the second volume of New Poems. A volume, Rilke entitled, not “part two”. That would just mean more of the same. But Der neuen Gedichte anderer Teil or “New Poems: Another Part.”

96

The implication is that the second volume — with its many parallel themes to the first volume — puts a new face on those themes and continues to grow.

97

In German to change your life is to “other” your life. So there’s not a great verbal leap from the title page “anderer Teil” (Another Part) to “dein Leben ändern” (change your life). It’s not hard to imagine a poet mulling the frontispiece to his second volume by thinking: “You have make not just a second volume, but a whole new start. You have to live another life.”

98

Which came first — another life or another part? It doesn’t really matter. But I think Du müßt dein Leben ändern and Der...anderer Teil echo and give weight to each other. And the correspondence shouldn’t be ignored.

X: Why?

99

The Rilke canon is particularly rich and varied. He presents us with a multitude of almost contradictory voices: The modernist non-believer capable of projecting himself into the reverence of the Book of Hours, or The Life of Mary. The stark naturalist of The Voices able to speak in the unadorned voice of a suicide, a drunkard, a beggar. The early formalist and the narrative master. The philosophical imagist of the Elegies. The ephemeral musician of the Orpheus Sonnets. His broad range and multiple personalities absolutely require multiple translators. It would take another Rilke to have the skills to tackle it all.

100

Beyond this, some of the individual poems — especially the Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus have a complexity of resonance and ambiguity that calls out for multiple interpretations. Perhaps “performance” is a better word for translating these pieces. If the objective is to enrich the English language, then there’s room for as many performances of Rilke as, say, interpretations of Bach. And these might be as varied as Wanda Landowska’s, Glenn Gould’s, Stefan Hussong’s and John Lewis’s — while remaining recognizably Rilke. Just as the above versions remain essentially Bach. In fact, it’s not hard to imagine Bach relaxing with the angels, listening to the hundreds of versions and transcriptions, and smiling. “Wow, look what they’ve done with my song.”

101

So what’s the conclusion? — Yes, I think multi layered, complex poets like Rilke do need to be retranslated almost continually. Not especially until we “get it right”. That’s just a beginning — because language lives and changes and poems written a hundred — or a thousand — years ago can only come alive for the first time again in a new language. German has only one Rilke — but we can find fresh Rilkes in every new generation. So long as translators return to the text — and themselves — rather than their predecessors.

102

But — and this is a big question: Rilke may now well be the most popular foreign language poet in the English speaking world. And if it’s his “standard” translated voice that people love, why would anyone want anything different? Do we, in fact, have to wait another twenty years or so for the current icon to go out of fashion, before anyone will accept a contrary look? That’s why I feel compelled to all this commentary, rather than just publishing the translation and be done with it.

Also see in this issue: Chris Edwards: So Not Orpheus: Rilke Renditions 1–11

Art Beck

Art Beck is a San Francisco poet and translator who has published three books of original poetry — most recently Summer With All Its Clothes Off (Gravida, 2005). And selections from Luxorius and Rilke in two translation volumes. His work has appeared in a number of anthologies and journals, including Translation Review, Two Lines, Artful Dodge, Alaska Quarterly and the 2004 anthology, California Poetry from the Gold Rush to the Present.. Centrum Arts features a profile: http://www.centrum.org/residencies/2007/05/found_in_transl.html