| Jacket 35 — Early 2008 | Jacket 35 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 14 printed pages long. It is copyright © Omar Pérez and Kent Johnson and Jacket magazine 2008.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/35/perez-ivb-johnson.shtml

JACKET

INTERVIEW

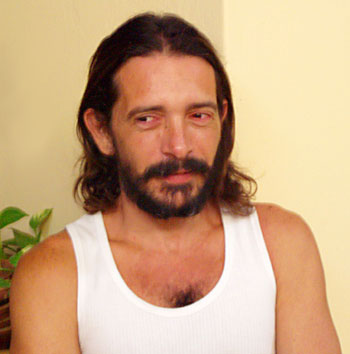

Omar Pérez

in conversation with

Kent Johnson

This interview was conducted via email during the last half of 2007.

1

Kent Johnson: You have lately lived both in Cuba and the Netherlands, moving between one of the world’s more open and permissive cultures, and one (as it is said in the U.S) that limits cultural freedom. Could you talk about this “doubled” kind of experience? How has this impacted your writing? Are you a different poet, in any way, in Cuba than you are in Holland? Do you feel greater freedom as a writer in one place than you do in another?

paragraph 2

Omar Pérez: Your question, or set of questions, should provide with a good excuse for an essay on relativity. More modest, though, I’ll merely try to go by the steps.

Omar Pérez

3

This go-between experience is clearly one of traveling, not only in space but mostly between, among, and around categories of living; a specific case of mutations which I call Kubanollandia: a southern creature searching for his roots in the ice. Being born and raised in a dream, however maimed, I find the capitalist world irreversibly primitive, based as it is on Profit & Competition. A poet will play; nevertheless, he should — in this case I don’t fear being normative — avoid being competitive. Those are not the ways of poetry. No matter how liberal and ecumenical the contemporary Dutch capitalism appears to be, one can hardly doubt that, given the chance, they would again crucify Vincent Van Gogh, and they would do it, once more, on logs of indifference.

4

Capitalistic culture, especially in the more refined, sophisticated stages or instances, typically lacks the basic hunger for the unknown which is swiftly replaced by all sorts of commonsensical phantasmagoria. No wonder Jan Peter Balkenende, the Dutch prime minister, has been nicknamed the Harry Potter of the Lowlands. Sueños de la razon, Goya would say. I despise the subsidized freedom to consume pot & XTC where the poet must find his way among a numb confederacy of know-it-alls.

5

As to the impact of extraneousness on writing, in nowadays Holland I would always be an allochtonous, as opposed to autochthonous, writer — it has produced in this case two different, though interdependent lines: the logbook and the verse, both Babelian and hopeful: esperanto, or, if you will, papiamento. Cubanology, the first, Lingua Franca, the second. And both bearing the same subtitle, or warning: “An investigation of the futility of pursuing happiness or wisdom.” Humoresque, natuurlijk, as such dramas should be delivered.

6

On the other hand, the issue of being different poets — which you, I dare say, have beautifully explored — is not only one of metaphysical, macaronic comedy, since the invitation to become a philosophical clown is a bit more than an outwardly devised experiment for the well informed; it is an experience in healing which is imposed, gently or not, by the self. And to heal yourself from freedom is at times as urgent as freeing yourself from oppression. The challenge could be that of translating some findings of the so called open society into the expectant marasmus of a so called closed system. And language, any language, is a good enough tool for such an enterprise. Finally, as Bob Dylan put it, “...most mysteriously. Are birds free from the chains of the sky-way?”

7

Is this then, in your view, one of poetry’s functions, to heal both writer and reader from too much freedom? It’s a fascinating, if discomfiting notion...

8

[Omar Pérez:] It is precisely because it’s discomfiting that it can save you. The Zen monk Kosen once said, “Freedom is an aspirin for the slaves.” And, you know, in several indigenous languages in America, the Lakota for instance, the word or concept for freedom simply does not exist. This could prove that the human being, or, at least, some human beings, can function without help of such viruses. But that doesn’t prevent us from going on piling opinions, philosophical, ideological, or whatever, upon the subject of freedom, mainly because of its commercial value, which you can plainly see in cigarette ads.

9

Taken like this, freedom is a tourist’s view of the universe, while poetry is still that look into the heart of things, sometimes rough and artless. Why then have we indulged in the practice of conceptual niceties and unspecific emotional innuendos and called it “expressive freedom”? Modern poetry and art has adopted the circumstantial values of the ego trip, which is nothing more than one of the synonyms our present day vulgata has for freedom.

10

Buddhism, and more specifically Zen Buddhism, has devoted a lot of effort to observe and equilibrate those trends, though sometimes it has also helped to create a private, or sectarian exit to the non-ego resort. The poet is the monk, as it was timely underlined by [José] Martí in his reflections on Whitman. Why then have we decided to relinquish this possibility in exchange for the freedom to produce somniferous conundrums and become perpetual scholars and awarded nitwits? It’s not exactly a free world: society, sex, market, etc. The best thing a poet can advocate: perhaps a nice, healthy free-fall into the disrepute of this reasonable world with its wide range of reasonable prices.

11

How did you come to be a “semi-expatriate” poet? Could you talk a bit about how this divided residency works out in real time?

12

[Omar Pérez:] I don’t live in Amsterdam anymore, nor was I ever part of any real or imaginary “diaspora.” I fell in love with a woman and a city, that’s all. I will share more details about my experience in The Netherlands as soon as Cubanology, a book in progress — a sort of haibun — is finished: It’s a three-year logbook which deals, precisely, with the experience of living between, at least, two worlds.

13

OK, but could you comment a bit, for our audience here, how the doubled experience has informed your poetry? What impact, if any, does it have on your literary position in Cuba and the reception of your work there?

14

[Omar Pérez:] Apart from quite a restricted number of friends, here in Cuba one gets very little feedback as to the value of one’s work, which is not so bad, after all. Literary position, I guess, is a business for literati, not for poets. What you call “doubled experience” has had a clear impact, though, in the core: perception, language, and that other half of your being you can call consciousness, if you want: consciousness, in the sense of basic awareness, not as intellectual chain production. Learning Dutch, thinking in English, translating the Mediterranean into Germanic moods, and vice-versa. All that can doubtlessly feed the poet’s little acre.

15

You had mentioned Zen. You are, indeed, a long-time practitioner of Zen Buddhism, and this practice naturally informs your writing in various ways, something that is evident from your collections Oiste hablar del gato de pelea and Canciones y letanias, for example. And it is extraordinarily interesting that you were at the heart, in the late 1990s, of the establishment of Cuba’s first Zen center, currently led by a Japanese teacher from the Soto lineage. You have talked a bit about this in a brief, wonderful essay, “The Zen Dojo in Habana,” translated by Kristin Dykstra.

16

Would you please talk about how you came to Buddhism, and more specifically, about the process of the sangha’s establishment in Havana. Was this process a difficult one, culturally and institutionally speaking? What resistances, if any, had to be overcome? And what has been the Zen center’s history since — its successes and challenges, its broader impact in Cuban culture? How do you see the role of Buddhism in a society where revolutionary ideas continue to mark daily experience and thought in such fundamental ways? And how do you see, if you’ll forgive this string of questions, the future of Zen in Cuba?

17

[Omar Pérez:] First of all, I must say that the first Cuban dojo was created in 1996 by Kosen Thibaut, a Frenchman disciple of Taisen Deshimaru. It was founded in the most irregular conditions: a rented house on the beach, in the hardcore of the so-called Special Period [The half-decade, or so, following the USSR’s collapse, when the Cuban economy was in acute crisis]. The site was, of course, provisory, as all sites have since then been, but the movable dojo has remained.Together with other five Cuban men and women, I was ordained a Zen monk a few weeks after September 11. Coincidence? Maybe, in the Tibetan Buddhist sense of “auspicious coincidence”... I believe the arrival of Zen Buddhism in Cuba, with master Kosen Thibaut, to be as important as Martí’s birth or the 1959 revolution; now it’s a matter of translation: It’s hard to understand that it’s not some kind of oriental vehicle we’re riding. Zazen is not Kawasaki or Hyundai. And it is not Bushido either.

18

From the very beginning, the master’s fundamental teaching has been: Only zazen is important, the rest is decoration. And this is a clearly revolutionary teaching. Yes, the process has been difficult both culturally and institutionally speaking. Cultural solutions, however collective, must go through individual consciousness. This is all the more true in Zen practice, and in any revolutionary practice whether it is poetry, economy or religion. So you have to translate through your own body of awareness, which comprises, needless to say, the physical body and its surroundings; one has to translate...

19

I have compared zazen to dancing, and, to put it in Red Pine’s terms, this is also dancing with the dead. The dead ones, in certain aspects of life, are sometimes much more alive than institution-minded living beings, which creates communicational hindrances of all sorts. But going back to the already mentioned basic teaching in our lineage, to make of Zen an institutional nice-and-easy social asset is not a priority.

20

The real impact of Zen practice in Cuban society is hard to measure. It’s too soon, and foolish, to define achievements or setbacks: this is no sport, or any kind of competitive activity. Meditation, whether sitting, walking, or whatever, is not the property or merit of any sect. It is the normal condition and, in so being, it’s a heritage common to all living beings. To talk, then, about developments is to miss the point. Development in relation to what? Even the notion of economic development is very dubious. If Buddhism is to have a role in Cuban life it must be in harmony with the basic ethical and natural values of this land; it must give, so to say, its blood and marrow to the soil, rather than being busy with official recognitions or hosannas.

21

On the other hand, after a decade or so, Zen practice has been put in contact with all sorts of people, has traveled through the island, sometimes, as it should, in an anonymous, unpretentious manner. And, I’m sure, the island will never be the same.

22

Yes, your question is a good one: “Development in relation to what?” If you’ll allow me to clarify my intent, I was wondering, in a somewhat banal sense, of Zen’s growth and influence in tangible, measurable ways: the extent to which the sangha has stimulated public interest, attracted new practitioners, extended its presence in other regions of the country, and so on. In particular, as someone who once edited an anthology of US Buddhist poets — an ever and rapidly growing literary “demographic” here, actually — I’m curious about Buddhism’s impact on the cultural arena in your country.

23

To what extent is Zen coming to intersect with the practices of artists and writers in Cuba? Or are there institutional, ideological factors that make it difficult for “cultural workers” there to openly embrace Buddhism?

24

[Omar Pérez:] You’re looking at things in the topsy-turvy manner of material interest. You want to know about achievements, like scholars who build anthologies seem to think that poetry’s health can be told by the numbers. This is not America, as you the American call it, though many would like it to be, in one way or another, explicitly America or implicitly America: the America of sudden realizations, and good old nirvana can be one of them! No green cards for this, my friend. Buddhism is simply to understand that all human beings, all beings, have a heart; reality itself has a heart pumping from the heart of nothingness. Try to figure it out in terms of cultural factors!

25

Well, as José Enrique Rodó says in his great work, Ariel, we creatures of the North are materialist by nature. I’m doing my best... So how does Buddhism fit into the Revolution, its ideals, its future? I realize the question may seem humorous to you. Feel free to deconstruct the phrase “fit into,” if need be, not to mention “ideals”...

26

[Omar Pérez:] I believe in ideals, even dogs have ideals. Why shouldn’t we? But, is it Buddhism which should fit into the revolution, or is it the other way around? Who can determine this? It’s a very common misunderstanding, and a very bad joke, to say that Buddhists are only busy taking a panoramic view of their navels, but this is exactly what politicians do. Their world is so tight, so compressed inside categories of production, of doing, of achievement, whether right or wrong, true or false...a bit of contemplation would be healthy for these so-called hyperactive revolutionaries who cannot find a place for their butts to settle and stop farthing around. You see, nowadays, anybody, whether in the capitalist or the socialist society, left or right, in cybernetics or sports, can be called a revolutionary as long as the enterprise is doing well and is aggressive enough. It’s very boring.

27

Fascinating, and I hope this interview doesn’t get you into any further trouble, of which you’ve had your share, I believe. But allow me to ask: What do some of your country’s ”hyperactive revolutionaries,” as you put it, seem to think about Zen so far? I’m thinking of Fidel’s famous dictum long ago, about the role of the artist in Cuba: “Inside the Revolution everything; outside the Revolution, nothing.” Is there any indication of suspicion, on their part, that Zen may be “outside the Revolution”? I assume they certainly don’t see the Revolution as inside Zen, as you suggest it may be!

28

[Omar Pérez:] How could I know what they think? Do they know what they think? That’s the question: do I really know what I think when immersed in the process of thinking? Inside and outside, you know...this is primitive thought. And insofar as it’s primitive it’s also basic, necessary thinking, but we are to go a bit further. Master Kosen, who taught the zazen posture in Cuba, has often remarked that the revolution is a process of nature, it’s nature’s nature, so to say... nothing to do with ideology, in the modern sense of the term. Ideology can function as a sort of common password to reality, but no password is magical enough to substitute reality.

29

You are multilingual — a translator from Italian, English, and Dutch. I think it’s good, in fact, to point out that we are conducting this interview in English... Lingua Franca is your latest book, yet unpublished, I believe, a kind of macaronic carnival in at least half a dozen languages, an absolutely singular work, I’d say. It’s funny, sad, confusing, clarifying, inspiring. Could you talk a bit about this latest project, its origins and purposes? Would you see such gestures of linguistic crossing becoming more common in poetry’s future?

30

[Omar Pérez:] Yes, of course. It’s part of the general scenario. Though still the poet has to keep a high degree of sovereignty regarding general trends; that’s the specific tendency in Lingua Franca: to find the individual’s universal language. At the same time, there’s some research on the origins of our common languages, from Sanskrit to Provencal, from Latin to Cuban vulgata, and, naturally, from Greek to silence, to respiration, and then again to rhythm. It sounds very bombastic, and in a way it is: The voice in Lingua Franca is mock-pedantic, like that of a scholarly clown, a Dantesque fool. I was a bit puzzled myself when I realized that, in poetry readings, people were smiling at or even laughing at these poems. Slowly, slowly, I realized that this was the hidden purpose of this investigation. Poetry can be cured of poetry.

31

Poetry can be cured of poetry?

32

[Omar Pérez:] Some people think that poetry is an intellectual thing. In Cuba, for instance, I don’t know if in the States it is the same, poets are usually put in the same line-up with intellectuals — writers, critics, philosophers (if there are any at all in this world!), not with artists, meaning musicians, painters, sculptors, actors, etc. This means that poets and their actions are seen as mainly matters of discourse, textual elaboration and, in a tacit way, solipsism. And even if they are, or could be, responsible for some conceptual beauty, they are expected to have very little to do with the real thing. The poet is not even a singer anymore, he is a parrot, a repeater of forms and ideas, so he is left alone in the playground where all sorts of clichés are recycled. This has a certain influence on the relationship he has with his ethos, and also with his environment, nature, and, ultimately, the whole universe.

33

How does this start? What’s the origin of such a misunderstanding and, if it’s still possible and relevant to know, when did this process of alienation begin? The Renaissance? The Middle Ages, or Christianity? Did this start with the invention of written language? I don’t know. Some references are useful, like the functions of poetry for the Nahuatl, the Provencal experience, etc. And also the African way, as expressed in the tradition of griots, or in the singing of anonymous, so to say, poetry of the Baka pigmies. But probably, even all this is a side issue as to the disease of poetry. Do we think that poetry is a doing? Do we actually make poetry? The verse, the poem, even the rhyme, the melody of poetry are the tip of the iceberg, they are just one familiar aspect of a huge reality which we call consciousness. We could say cosmic consciousness, universal consciousness.

34

The poet is thus an explorer of consciousness, so maybe he can heal himself from himself, from his belief that poetry is just a question of imagination and form and ego and social representation, etc. Poetry is a natural function, like god, or DNA, or rain. The fact that we can give notice of it does not mean that we make it.

35

Those last two sentences are quite wonderful. The notion seems somewhat mystical. But how would you say the medium of language relates to that “natural function”? Is it at one with the function, or does it filter the function?

36

[Omar Pérez:] Wonderful question! Yet it still dwells on a separateness as to function and being. Would you say the liver is at one with energy or it just helps to filter it? Now, I invite you to use your poetical imagination to try to devise what the liver would answer. The same thing with the poet: he’s not supposed to live in two separate worlds, one functional, the other devoted to the essential.

37

OK, a change of topic: In the US, Omar, when most people think about Cuban literature since the Revolution, they think of a pretty closed, officially constrained field. The Heberto Padilla affair, or the fate of Reinaldo Arenas, perhaps also the earlier marginalization of the great José Lezama Lima — cases like these still mark, for most US readers, a general negative impression. But am I right that today things are a good deal more complex and dimensioned than that? That there is considerable ferment, much open conflict and challenge in Cuban literature and the arts?

38

You, for instance, in the 90s, were at the core of a notorious “non-official” group of intellectuals called Paideia, which was the subject of intense debate in Cuban cultural circles. Could you give us a synopsis of the nature of that group, the political and cultural fall-out of the experience, the place of the Paideia phenomenon in Cuba’s recent literary culture? More broadly, and I do realize it is a pretty broad request, could you speak a bit of the articulation between creative freedom and social constraint in contemporary Cuban poetry, how this tension has evolved over the course of the Revolution?

39

[Omar Pérez:] Paideia was a good, adolescent try, but consistent enough to defy the notion of Cuba as a cultural black hole, which I reject, as you do, if I might say so. The Paideia process described a transition from the all too common artistic and intellectual self-interest to a broader view of social, political responsibilities. In this sense, and with its peculiar intensities, it is still a unique phenomenon in Cuban cultural history of the last thirty or forty years. I don’t know what Paideia means nowadays for younger artists and intellectuals, if it means something. For those who stayed until the very end, however disappointing, it was an honest exercise in hopeless goodwill, in action without merit or reward. And this is good enough, as formative practice, in a world where you cannot afford to deliberately play the underdog.

40

Throughout this conversation, I think, we have been dealing mainly with that articulation, or tension you describe: creative freedom and social constraint. They are two faces of the same process: you cannot have one without the other if you want to grow out of the belly of convention and tradition. We are not children of the State anymore, and Paideia was, precisely, the starting point of a coming-of-age process. Now we are able to see the first fruits of this odyssey.

41

In what ways is Cuban culture now seeing “the first fruits of this odyssey”? In general, could you please speak more specifically of Paideia. How did it form and who were its members? What were you reading and discussing? Aside from yourself, what’s become of some of its leading members?

42

[Omar Pérez:] I think Cubista, an online Cuban magazine (in Spanish) has made a pretty good dossier on this where one can find all sort of details and ideas about Paideia.

43

Now, if you don’t mind, I’d rather talk about something else.

44

Forgive me for insisting, and correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t Paideia have some predecessors, so to speak? During the 80s, in particular, there was a period of intense formal and theoretical experiment among younger artists studying at the Castillo de la Fuerza Real — though this was not exactly met with official approval, and a fairly conservative period of cultural policy followed, after Armando Hart’s replacement as Minister of Culture, from what I understand.

45

But in recent years, there seems to be a lot of renewed ferment in the Cuban visual arts — even to the point of barely veiled protest and satire of ideological institutions. I’m thinking of the collective of young artists Los Carpinteros, for example, who have gained considerable international fame. Would they be one of those “fruits” of the Paideia experience in some way?

46

[Omar Pérez:] I don’t think so, but they are good carpenters.

47

OK, but have there been in the realm of poetry any critical or “oppositional” formations in the past decade analogous to Los Carpinteros? For most of the Revolution, a realist, politically committed poetics of testimony has been the dominant paradigm — one that was influentially promoted at international levels through the prestigious Casa de las Americas and its many publications. Are there groupings of poets in Cuba who have emerged of late as alternatives to some of the precepts of this mode?

48

[Omar Pérez:] What exactly do you mean by “most of the revolution”? I started to write and publish in the early eighties, that is, some 25 years ago. I think you make a confusion here between concepts such as realism, commitment, political or otherwise, testimony and the flat ideological allegiance of certain Cuban writers and artists especially from the 70s onwards. Poetry must always have elements of testimony and is based on commitment — as Pasternak put it, the poet is a prisoner of eternity. A Greek philologist once told me that the ancient meaning of the word Homer, Omeros, is “hostage.” What kind of intellectual stance of radical criticism can overcome such bondage between the poet and his ethos, his language, or languages, his spiritual motherland, his own visions of politics, economy, and so forth? The poet does not depend on a so-called factual yes-or-no relationship with circumstances. There is a difference between the truly poetical life experience — and I have to acknowledge that even poetical and poetry are limiting ideas — and the artistic, textual, discursive competitive hanky-panky. It is the same as the difference between an odyssey and a sunny weekend sailing contest in a harbor…

49

There is a group of poets from Alamar, in the outskirts of Havana, who call themselves OMNI. They have been celebrating for several years a sort of festival they call Poesía sin fin (Poetry without end). Maybe one day they’ll achieve some greater international recognition, but what they do now is good enough.

50

Omar, you earlier referred, though without mentioning them specifically, to the writings of the fictional Araki Yasusada, of which I have been caretaker for numerous years now. And you have translated, brilliantly, some of those poems and prose pieces into Spanish. I have to ask — self-interested as I suppose the question is — what your opinion is on the considerable controversy the Yasusada work has caused.

51

What would your view be regarding those sometimes very harsh critiques leveled against Yasusada in the West — namely that the work is an inappropriate “hoax,” an unethical faking of identity and manipulative appropriation of the “other”? I’m very curious what you might think of this from a Buddhist perspective, for example. Or simply from the perspective of a poet in a culture whose “otherness” has itself been widely appropriated…

52

[Omar Pérez:] As you very well know, many controversies, especially those pointing at ethical values, have very little ground. No limits should be put on creation on the basis of politically correct innuendos. The creation of characters, the forging up of texts, and even of realities and worlds, such as utopias, is as old as literature itself. Don Quijote himself is a necessary hoax. And as to the appropriation of the other...this was eventually very well understood by Rimbaud when he said JE est un autre. I is another, which is technically true, from the Buddhist perspective at least. The quality of creation itself is what we should be concerned with; the rest is the customary vice of putting a label of clear cut ownership to everything around us, even trees and seeds. Now, there is a very close relationship between trees and paper, between characters and seeds, that’s probably the reason of so much copyright discussion.

53

In her excellent essay at the back of the new translation of Algo de lo sagrado (Something of the Sacred, Factory School, 2007), Kristin Dykstra links your work to the “neo-baroque” tradition. The most famous poet associated with neo-baroque style is of course Jose Lezama Lima, whom I mentioned previously. How important has his work been in your own development as a poet?

54

[Omar Pérez:] I can only talk about a fascination; later on I also studied a little of his poetic system, as it is formulated in Paradiso, or the essays, such as Las eras imaginarias...then I found out that, as every great poet, he was very much concerned with breathing. Well, of course, he was asthmatic and a cigar smoker at the same time, but what I mean to say is that he left specific indications regarding the body-spirit relationship, as it is expressed in breathing. I don’t agree with the term “baroque” as applied to Lezama, however: it doesn’t say much and it may lead to confusion. You can learn a lot from Lezama without knowing that he is considered a neo-baroque writer. He is Christian and has a taste for complexities, for comprehensive structures and that which he himself called “golosinas de la inteligencia,” but that doesn’t bring him any closer to Handel or Bernini.

55

Anyway, the point of interest for me is to observe his observation. He is very accurate, I would even say scientific: It is as though, as he describes his kitchen floor, he’d make us feel he’s talking about the surface of Mars. He’s also a hell of an improviser within the frame of a general structure, and though it’s true that Bach is said to have done the same thing, as Keith Jarret said once, we don’t actually know what Bach was doing with improvisation because there are no records of it.

56

Speaking of improvisation within a general structure, there are multiple references to baseball in Algo de lo sagrado: the sport seems almost a metaphor-making mechanism for you. I’m interested in this, partly, because a centrally important poet to the US “avant-garde,” Jack Spicer, who died in the mid- 1960s (and arguably a kind of neo-baroque poet himself, actually), uses baseball quite often as metaphor in his work. What’s the fascination with baseball for you vis a vis your poetry? There seems to be some kind of engagement there with the interplay of strict rules and unbounded freedom?

57

[Omar Pérez:] Yes, this is exactly what happens with the world of physics. And baseball is a good chance to take a look at it from an engaging viewpoint, a fun lab. But also, you have access to all the significations related to homeland, identity, and so forth, which play an important role, for better or worse, in sports. You have the collective-emotions pool to plunge into, etc; and then you have the flexibility of language put to the test of an everyday, dynamic practice, and what comes of it, sort of lingua franca as well, where English and Cuban Spanish mingle.

58

You mentioned that Cubanology was “a sort of haibun,” and in your work, namely in Oiste hablar del gato de pelea?, where haiku is prominent, you have engaged forms that have historic relation to Buddhism. One thing I find fascinating about literature in the Zen tradition (as well as its other arts) is the wide variety of formal options it seems to proffer: from modes and genres of strict prosody and form, to those that would seem to reject formal constraint altogether. And your own work seems to partake of this fluid spectrum, ranging from the formally wrought, as in Oiste hablar del gato de pelea, to open, wildly idiosyncratic language and structure, as in Lingua Franca. What about this apparent contradiction?

59

I ask this in part because in my country there is a great division, even outright hostility, between so-called “innovative” poets who write in linguistically experimental form and those (arguably the dominant tendency) who write in modes that approximate the patterns of common discourse. I assume somewhat similar divisions also exist in Cuba, though perhaps not so acutely as in the US… I’m wondering if you might see Zen as potentially opening up a space where such prosodic embattlements, as it were, are rendered somewhat trivial? Or not?

60

[Omar Pérez:] On the one hand, to think of Zen as medicine for literary controversies...but, on the other, it’s true that a little bit of observation and concentration can open space, and eradicate time. There is no contradiction whatsoever inside the poetic experience; we live in the world of contradictions, the world of poetry, as the Nahuas see it, which is the only real harmonic world. What difference does it make to sing in sonnets or raps? The structure is necessary, agreed, but even a massive steel frame structure can dance with the wind. What about poems? Do they really need further discussion? Should we pay so much respect to form and structure? I think not. We might as well pay due homage to poetry wherever it really is: the world of trees, the rhythm of the seas, the distant presence of the stars, etc. But it is also true that if we did so, the literary industry would decay and die, we would stop trading trees for paper. Now, I don’t know if Zen is something different from basic, fundamental poetry, and Zen is also responsible for the creation of a good deal of form and structure. This is a contradiction, but not one we should get angry about.

61

Kristin Dykstra, to mention your very fine translator again, has recently published a fascinating essay in the journal Mandorla [reprinted here at Jacket]. Therein, she discusses the “open secret” in Cuba that your biological father is Ernesto “Che” Guevara. I realize that this is something you have chosen to not talk about publicly. But now that her essay is out, and now that your work is becoming increasingly known in English and a number of European languages, the matter is of obvious interest — and will be, of course, to future critics of your work. So allow me to ask you. How do you feel about Kristin Dykstra’s essay and her identification of Che Guevara as your father? More to the point, could you speak about what the meaning for you of such a relationship has been?

62

[Omar Pérez:] I should re-read Kristin’s essay in order to give you a correct answer. She’s an honest, perceptive scholar. Even if I didn’t agree with everything she says, I would be more than happy to share certain things with her. It’s not much, I don’t have much to say in this respect. In fact, I think I’ve said it all.

63

Thank you very much Omar. This has been most interesting.

64

[Omar Pérez:] No, thank you very much.