| Jacket 35 — Early 2008 | Jacket 35 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 5 printed pages long. It is copyright © Steve Bradbury and Jacket magazine 2008.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/35/bradbury-poetry-now.shtml

1

As the ink dries on the “2008 Calendar” issue of Xianzai Shi, or Poetry Now [formerly On_Time_Poetry], rumor has it that the editors of this Taipei-based avant-garde annual are calling it quits. If they do, it will be a sad day for poetry on the “Ilha Formosa,” for in its brief six-year history, Poetry Now has served up more interesting verse in more interesting formats than the rest of the island’s journals combined. Edited by the poets A Weng, Hsia Yü, Hung Hung, Ling Yu, Shiah Shiah, and Tseng Shu-mei, Poetry Now was founded on the cusp of the new century to fill the void that was left when Xiandai Shi [Modern Poetry], the organ of the Modernist Poetry Society, which had long provided a home and forum for Taiwan’s more progressive poets, closed up shop in 1997.[1] Equally prominent on the minds of Poetry Now founding editors was the desire to provide a platform for experimenting with new themes and formats that would both enlarge the notion of poetic writing and attract the interest of younger readers with little interest in or exposure to contemporary poetry.

paragraph 2

Much of the credit for the journal’s success in doing just that must go to Hsia Yü, who has long been the island’s most dynamic force for poetic innovation and is the only poet in the editorial coalition to have attracted a significant fan base. The author and designer of five volumes of poetry that each in their own way aspire to the condition of an artist’s book — of which the most recent and notable example is a truly sui generis bilingual volume entitled Pink Noise, which has the distinction of being the world’s first transparent codex as well as the first collaboration between a Chinese poet and a machine translator — the maverick poet has made substantial contributions to all of the journal’s issues and was personally responsible for editing and co-designing what are, in my opinion, the two most interesting issues to have appeared thus far in terms of both their design and editorial concept.[2]

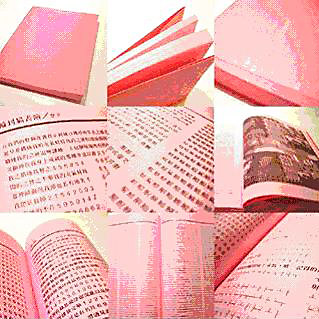

3

The first of these was Poetry Now 2, which, as I pointed out in a Taipei cultural weekly some years ago, was one of the most subversion contributions to the art of book design since William Morris had Das Kapital bound in turquoise goatskin.[3] Printed on pink tissue-thin paper in miniscule type, with a single poem per page and the blank space filled with columns of numbers in random sequences, the issue, which was bound in pink embossed vinyl, looked like nothing so much as a telephone book for a life-size pomo Barbie Doll. And like a telephone book, Poetry Now 2, the “Publication Guaranteed” issue, was radically democratic, for Hsia Yü published every submission she received, which turned out to be a whopping 546 poems by 167 individuals (many of whom had evidently never published a word in their life) in a call for submissions that purportedly lasted a mere 72 hours. Although the quality of the poetry is understandably uneven, the issue is chock-a-block with interesting verse and represents a fascinating cross-section of the island’s “body poetic.”

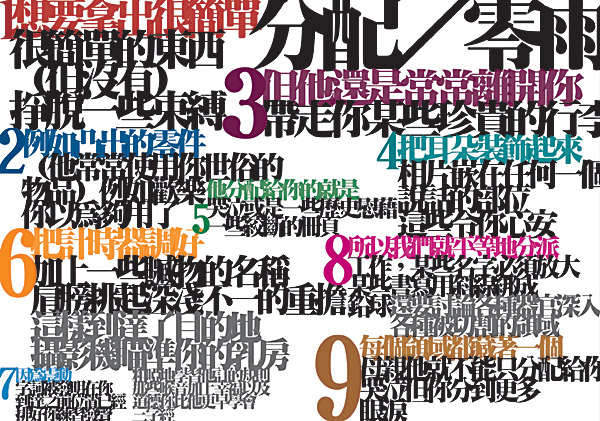

4

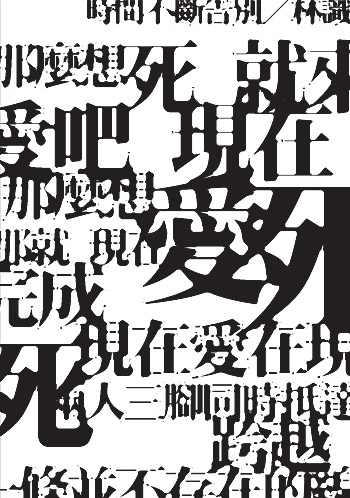

The second issue Hsia Yü edited, Poetry Now 5, was even more radical in its conception. Named after the hand-written wall-mounted posters that came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution and subsequent “Democracy Wall Movement,” the “Poetry Now Dazibao” issue was designed as a series of nine sumptuously beautiful full-color wall posters, one poem per poster, folded into the form of a broadsheet newspaper that can be read as both a collection of poetry and a celebration of the beauty and materiality of the Chinese written character as medium of poetic expression. Indeed, Hsia Yü and her co-designer, a talented young graphic artist named Hong Yiqi, were so intent on drawing attention to the iconic nature of the Chinese characters that two of the poems are virtually unreadable and several others are partially illegible. Interestingly, most of the sections that are legible read like autonomous poems and those that aren’t are as visually engaging as a late Jackson Pollack. More interesting still, the issue contained a Chinese-English bilingual “Call to Editors around the World” to produce a poetry Dazibao of their own.[4] According to Hsia Yü, editors as far as Krakow have expressed interest in the idea, but as far as I know no one has yet produced such an issue, and I would be surprised if they did. The Poetry Now Dazibao cost the editors a fortune in printing costs, only part of which have been recouped because of the difficulties bookstore owners have had in displaying a broadsheet newspaper cum poster series in stores designed to sell books.

5

If the other issues of Poetry Now have been more conventional in terms of their design and editorial concepts, they have been no less interesting or progressive in terms of the journal’s agenda. The first issue, which was collectively edited, devoted much of its space to song lyrics by Chinese poets who have been inspired by the work of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, and included tributes to, as well as translations of, the work of these two great poet songwriters. Although the edition had no publicity to speak of, the first print run sold out in a matter of weeks. Poetry Now 3, an antiwar issue assembled by poet and filmmaker Hong Hong, who curates the annual Taipei Poetry Festival, and beautifully designed and illustrated by the poet and designer Su Huiyu in the disheartening months leading up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, was filled with antiwar poems by local writers as well as translations of the work of a number of Western and Middle Eastern poets, among them Saadi Youssef, Yehuda Amichai, and the great Forugh Farrokhzad, and contained some of the most political and erotic imagery I have ever seen in a poetry journal. The next issue of Poetry Now, which was edited by A Weng, who teaches literature at one of the local universities, was the journal’s most conventional issue in terms of its design, but it included some of Poetry Now’s most engaging features to date, notably a handful of provocative “lower body” poems by the Beijing “glamlit” poet Yin Lichuan, a “trailer” to the aforementioned Pink Noise, and a profile of the local poet and wood-cut artist Shiah Shiah, who subsequently joined the Poetry Now editorial coalition and has made a name for herself as a designer of poetry-related novelty items such as “Poetry in an Egg” and “Poetry in a Matchbox.”[5]

6

Which brings me to the sixth and most recent issue of Poetry Now. Hong Hong came up with the idea of doing a page-a-day calendar issue, but the issue was collectively edited and the design work was once again done by Hong Yiqi, who went to no-small-trouble to vary the formatting of the individual pages so as to mark the journal’s aesthetic distance from the countless commercial calendars that go on sale in Taiwan at this time of year. Although the page-a-day format put a significant crimp on the length of the poems (none exceed fifty words and most are much shorter than that) the concessions to length were more than made up for by the sheer number and diversity of inclusions. The Poetry Now “2008 Calendar” issue has more than three hundred poems written in a range of styles and genres from haiku to concrete and most everything else between including snippets of text that read like commercial logos and classified ads as well as some actual ads that were evidently paid for by bookstore owners, sympathetic poets and designers, and other “friends” of the journal. The issue also has a fair number of foreign language poems, which I helped the editors solicit, along with a dozen or so English translations of short poems originally written in Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, and a few other European languages. Initial orders for the “2008 calendar” have been brisk, but even if this issue of Poetry Now turns a profit it is uncertain whether the journal will continue.

7

Tseng Shu-mei, who works in advertising and was one of the journal’s founding editors but has yet to edit an issue, has suggested the idea of doing a Poetry Now with a food and drink theme. But while such an issue could put the journal in the black, it could also take the edge off its poetic agenda. Compounding the problem is that Hsia Yü and Hung Hung, who have always been the most active of the Poetry Now editors, have been stretched fairly thin by their own projects, most of which have been quite costly and time consuming, and from the table talk at the editorial meetings I attended, I gather that they have lost some of their enthusiasm for editing the journal and I doubt that any of the other editors have the time and energy to take up the slack.[6] I suppose one can only hope for the best and in the meantime be grateful for the six issues that have appeared. Since Poetry Now is unavailable overseas and most of the issues have long been out of print, let me offer this sampling of work from the new “2008 Calendar” issue along with a handful of personal favorites from previous issues. Unless otherwise noted, the translations are mine.

from the new Poetry Now “Calendar Issue”

January 16

Liu Kexiang

Formosa through the Eyes of an Ornithologist

Island. Isolated

prospects. Self-satisfied

bird. Without wings

February 28, Peace Memorial Day [61st anniversary of the “228 Massacre”]

Hung Hung

We Must/

Not Forget

We must not

Forget

translated by Zona Yi-ping Tsou

April 21

Huang Shu

Spring muck —

stray dog sleeping

on a rock

[original in Japanese]

June 6

John Tranter

Hawaiian Haiku

In Honolulu

nobody watches

Hawai’i Five-O

[original in English]

July 31

Ye Mimi

Practice your haiku by ear

slope of saw-tooth grass/ bevy of ringdoves

floating conversation/ beer

August 5

Yuan Qiongqiong

The Fish

In the sunlight

the shimmering fish

move by

moving the river water

to words

Double Nine, “Dog Day”

Hsia Yü

I am a dog you are my bitch

He sniffed about he wagged his tail

and I interpreted

what he said was this: perfect

I am a dog you are my bitch

September 25

Yu Jian

363

a police siren screams along a main road

autumn pokes out its tongues in the dark

I’m enriched by my terror

translated by Simon Patton

October 21

Guillermo Boido

Underdevelopment

between rebellion and fear

a man carries his corpse

on his shoulder

translated by Lisa Rose Bradford

December 11

Suzanne Jill Levine

Butterflies

Nevertheless

Once they’ve given birth

There’s nothing left

[original in English]

from the Poetry Now archive

Liu Zheting

Without beginning without end

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

123456789

987654321

Hsia Yü

I don’t know when it happened that I came to be so comfortable

Thanks to everyone for their thoughtful email

Comments and phone calls

Hot soup, soft bread, mashed potatoes and —

Genius of all genius — stuffing. Thanksgiving stuffing

No one ever suspects the Thanksgiving

Stuffing

Warm, mushy and savory

I’m actually anxious about the whole thing

The horror stories alone from my Monday

Morning meeting were enough to turn my stomach and

Make me think that maybe I could live with the headaches

For the rest of my life if it didn’t mean skipping out

On this delightful rite of passage

Luck and love really are on my side

I don’t know when it happened that I came to be so comfortable

Being naked in front of strangers

[original in English]

Ge Chu (葛楚)

I thought I’d tossed my feminism in the can

I thought I’d tossed my feminism in the can

like an expired syringe on the verge of corroding now

that I am back in the pink of health but

the bastards keep reminding me it might not be

a bad idea to keep it close at hand for self-defense

translated by Lily Wong

Sun Rihan (孫日含)

With Regard to Memory

I died that year

I can’t remember there was a spring a grove in full flower

red ones so red they were violet violet ones so violet they turned black

littered the ground not a withered one among them

just blooming away but when they started blooming

I can’t remember although I did hear cicadas grinding away

there was a summer that year we went down by the seashore

there was a moon on that sea and a sun as well

the sea was huge the breeze never faltered whether there were waves

I can’t recall

in fall we fell in love

chasing each other through the sunflowered field

we went in and never came out

and winter? where did we go in winter?

I can’t recall I know we danced remember?

maybe that was summer can’t be the rhythm of the waves was much too urgent

it must have been the grove it can’t be you never went to that grove

was in full flower red ones so red they were violet violet ones so

violet they turned black littered the ground

you raised your head above the sunflowers

your eyes narrowed into a fine line

the breeze by the seashore mussed your hair

the cicadas were grinding way but the breeze didn’t make a sound

where did you go off to?

there wasn’t any winter that year

I died in the spring the grove was in full flower

I was buried by the seashore the sunflowers nodded their heads

so where did winter go? I know we danced

do you remember that song? hum it for me one more time

O yes now I remember

winter came before the spring

translated by Lily Wong

A Liu

Preserves

When you died I didn’t know

The desk is cloaked with dust

Carried off by Lord knows who

Still, there comes a morning

The air’s a light blue

The chairs refuse to speak

Each with a character all its own

Not the trace of a black hair to be found

A slight cramp in a finger or two

After calamity

You’re left dreadfully pinched

You’ve been gone so long

I can finally feel the pain

Slowly

Rounding this room

translated by Zona Yi-ping Tsou

Su Huiyu

I Tried to Become a Calamity

In the end I had to admit

What’s left of this old thing called sorrow ain’t so very special after all

translated by Lily Wong

Ye Mimi

[You can listen to an MP3 audio recording

of the poet reading this poem in Mandarin.]

A Moth Laid Its Eggs in My Armpit, and Then It Died

one day there’ll come a day / when the rain will not be wet / the avenue uneven / the grass undry umbrellas

unbroken / the sky bent out of shape / a day when sand and surf have gone their separate ways

/ the breeze unveiled its fine-tooth milk-teeth / and clouds have it all over fog for puttin’ on a happy face

then everyone will / move into their very own phone booth / keep a puppy at the welcome mat /

/ or a peacock / or a cat

and every fourteen days they’ll get a bag of coins / every fortnight a can of air freshener

/ have their hair cropped back just like a serving dish / don a pair of dark rimmed glasses

trench coats in winter / swimwear come summer / sandal size unspecified

/ their socks inclining toward an apple / green

someone calls up / someone else / and that someone

calls up yet another someone

/ and so it goes / from one someone to the next

until that last someone rings up / the first one / one day

there’ll come a day

he says / hey / and the first one too says / hey

he says /

last night / he says / a moth laid its eggs in my armpit

/ O / exclaims the first one

and then it died / he didn’t have a chance to add

/ as he hung up the phone / and left them all hanging

high

when the Dragon Boat Festival (a.k.a. Poet’s Day) comes ‘round each year / they’ll all trade phone booths

/ take their cat / their peacock / or their puppy /

and when they’ve finished going at it tooth and nail / they’ll all rub up against each other

/ and play a polonaise / with the ring tones on their phones

/ thus they’ll pass their one and only holiday of the year

who are you / she says

waterfall / he answers / listlessly

who are you / she says / beside herself / in a maze / mint / as she directs her question into the phone

you know / water / falls

with a sound that cuts off and clamps down / on the whole kit and caboodle

/ like a piano lid / a pot top / or a manhole cover / that kind

/ he says / all over again

I love you / she says

he drowns her out / prestissimo con brio

in an airtight phone booth / made of glass / you feel as though you’re sitting in a limo

/ absorbing the scenery and being absorbed in turn / as you’re effortlessly carried on your way

the conversation they fashion cascades like ticker tape / out of their mouths and into their ear

/ canals and forms a little heap in the cockles of their hearts

one day there’ll come a day / when everyone’ll have exhausted every language there is / repeated every puffed-up metaphor

to everyone they know

every tired turn of phrase / every long-winded grievance and expression of affection

that’s when / they’ll / twist their phone cords into a corkscrew spiral

/ and in one fell swoop / flourish their scissors snip / snip / off with their handsets!

that’s when they’ll get a Bloody Mary / and the lyrics to a thriving song

/ in a gesture of recognition they’ll savor forever

and the song will go like this

/ O / don’t you say a thing

/ O / don’t you have a fling

/ for when our fins take wing / we’ll make the rafters ring

/ so don’t you say / O / don’t you say a thing

and everyone will want to sing it

/ and when they’re done blurt ※○&*◎

/ i.e., a single / barely audible / frig’n!

with a tone like an olive / divinely / dirt-free

one day there’ll come a day

/ when every butterfly will be a lopsided carpenter’s square / every camel sport a hill

/ every bridge throw on an air of gloom more fearful than a viper

/ the ant will be mightier than the bullet / more powerful

then everyone will / move into their very own phone booth

/ and there they will converse in every discourse / like a high-speed / juicer

/ mouthing a wind chime’s hachoo

Editor’s note: Steve Bradbury’s translations of Yuan Qiongqiong’s “The Fish” and Ye Mimi’s “A Moth Laid Its Eggs in My Armpit, and Then It Died” originally appeared in (respectively) Mid-American Review and Hayden’s Ferry Review. Lily Wong’s translations of Ge Chu’s “I thought I’d tossed my feminism in the can,” Sun Rihan’s “With Regard to memory,” and Su Huiyu’s “I Tried to Become a Calamity” originally appeared in Enpots, the now-defunct English-language supplement of the Taipei-based free cultural weekly, Pots: The Voice of Generation Next. All translations and original English-language poems are the property of their respective translators/authors. All rights reserved.

[1] For a discussion of Xiandai shi, see the introduction to Michelle Yeh and N.G.D. Malmqvist’s Frontier Taiwan: An Anthology of Chinese Poetry (New York: University of Columbia Press, 2001).

[2] For a discussion of Pink Noise, see my interview of Hsia Yü in the forthcoming Zoland Poetry, which also contains excerpts and back translations of three of the poems in the volume.

[3] The description appeared in a review of Poetry Now 3 published in the March 4, 2005 issue of Enpots, the now defunct English-language supplement of Pots: The Voice of Generation Next.

[4] This call to editors can be read on the Poetry Now blog (http://poetrynow2002.blogspot.com), which also has thumbnails of the journal’s covers.

[5] I have an interview of Yin Lichuan in the October 10, 2005 issue of Pots: The Voice of Generation Next which includes translations of her poetry and is available online at http://publish.pots.com.tw/english/Features/2005/10/20/382_17_Main/. I have also written a piece on Shiah Shiah in the December 16. 2005 issue of the same journal, but this has not been posted online.

[6] Hsia Yü spent a fortune to print the first edition of Pink Noise, which sold like hotcakes but at a considerable financial loss to the poet. Hung Hung is in even more straightened circumstances, as he borrowed heavily to help finance his new film, The Wall Passer, which unfortunately did very poorly at the box office.