|

This is Jacket # 2 | # 2 Contents | Homepage | “Marginalization” |

|

|

This paper is taken from the Vol. 1 No. 4 May 1997 pamphlet in The Impercipient Lecture Series, edited and published by Jennifer Moxley and Steve Evans in Providence, Rhode Island, and is 4,000 words or about nine printed pages long. At the risk of raising the suspicion that I ventured no further than the first page of The Marginalization of Poetry, a scant ten lines into the opening chapter/poem (not counting those richly “telling” acknowledgments), I want to offer three additional speech-acts to the one Perelman himself starts with, Jack Spicer’s line from the poem “Thing Language,” published the year I was born — “no one listens to poetry.” Spicer is reworking familiar terrain in this line, echoing — to take only one example — his contribution to a 1949 forum in Berkeley’s Occident magazine, which almost as famously begins: “Here we are, holding a ghostly symposium, five poets holding forth on their peculiar problems. One will say magic: one will say God; one will say form. When my turn comes I can only ask an embarrassing question ’Why is nobody here? Who is listening to us?’ ” (One Night Stand 90). [ The Three Speech Acts ]Adorno once observed that “the soundness of a conception can be judged by whether it causes one quotation to summon another. Where thought has opened up one cell of reality,” he wrote, “it should, without violence by the subject, penetrate the next. It proves its relation to the object as soon as other objects crystallize around it. In the light that it casts on its chosen substance, others begin to glow” (Minima Moralia 87). While my object — our shared object — is Bob Perelman’s 1996 Princeton University Press book, a hearing-aid held to the deaf ear of the academy — I will proceed in the somewhat oblique, prismatic fashion recommended by Adorno. The three speech-acts summoned by Spicer’s “no one listens to poetry” and “why is nobody here” (a single utterance bifurcated around the pun on hear/here?) are all in fact variations on a declaration of presence, in one instance “I am here,” in the second case, “I am (still) here,” and, finally, in what I’ll call our case, “We are here (now).” The nearly-identical nature of these statements proves a point that Perelman himself makes by way of Hegel about those other two Bobs, Creeley and Grenier, and their insistence on “avant-garde particulars.” Perelman recalls Hegel’s demolition of naïve verbal reference in the first chapter of the Phenomenology, in which the “believer in sense-certainty [is asked] to write down a present fact: when the statement that it is night is read at noon, it turns out to be perfectly false” (45). It is such an ineradicable gap that Creeley sounds in a poem like this one from Pieces, and I quote: “Here here / here. Here.” The dialectic of “deixis” where the linguistic form ostensibly most conducive to the particular and specific is shown to in fact be a universal — is what gets the whole Hegelian show — not to mention the best sequences in Buster Keaton films (think of Sherlock, Jr. for example) — under way. But that’s another story. What deictic utterances direct us to is the frame or situation in which that utterance takes place and that is what I now want to sketch for you: three frames around an identical-seeming deictic: I/we are here. [ A Constitutive Blind Spot ]The speaker in the first instance is a startling young French girl named Aliette Legendre in Buñuel’s great paratactic non-narrative meditation on the opening lines of the Communist manifesto, The Phantom of Liberty (1974). Her “je suis là” is uttered at the juncture where three institutions — the bourgeois family, the school, and the law — join to disappear her. [ The opening lines of the Communist Manifesto: “A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of Communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police spies...”]I would hate to be too subtle about this: I very plainly hope to

make you hear her “je suis là” as I do — as a voice

of poetry not so much marginalized as consigned to a constitutive

blindspot. The locus of the second utterance is also French and

bears the proper name perhaps most closely associated with

poetry’s disappearance into that constitutive blind spot in

capitalist modernity; I mean Rimbaud. Aliette’s passage into

this blind spot is coded by Buñuel in institutional terms. The

Rimbaud who ends his Commune-period poem “What’s it matter

to us, my heart” with the words: “It is nothing: I am

here; I am still here” is punctuating a vision of sublimely

totalizing (as opposed to marginalizing) political

transformation. |

|

|

Luis Buñuel The third and last utterance — “We are here” — is not disjunctive in this way, since we are here. But as Jean-Luc Nancy once said in and of San Diego: “Who are we, here in San Diego, Americans, French, Chicanos, Japanese, Greeks, Koreans. Which is our tongue? ... We make unlikely a we.” The implausible community convened here tonight — through the good planning and sweated details, it must be said, of Sean Killian and Dan Machlin — raises the question of what our being here has to do with The Marginalization of Poetry, whether those words are inside or outside italics. We who are here hardly comprise a stable synthesis, or even for that matter a synchronization, though what time it is is a question still worth asking, if only to remind us that institutional chronometers seldom can tell us the time of practice, a fact with ramifications not just for poetic but for intellectual practice as well. Of the interfering patterns and temporalities that I know are operative in the unstable synthesis we make up, those at the border between Formation (and its distinctive rhetoric and practice of autonomy) and Institution (with its rhetoric and practice of complicity) are perhaps the most noticeable, but there is another unstable transition zone constituted around “generation” as well. I Am Here.

|

|

|

Buñuel [ “Search all of Paris .. “ ]Sizing her up again the Inspector notes her blue coat, black shoes, white socks. An officer is now called in. “Search all of Paris, you must find this child.” Upon receiving the small slip with the physical description on it he looks to Aliette and asks “is she the one?” Receiving the answer “yes, why” he asks whether they can take her along. “No just take a look at her so you’ll recognize her,” is the Inspector’s response. The officer approaches, seizes Aliette by the shoulders, brusquely straightens her out, takes a full long look at her, throwing open her coat to note the style of her blouse. Firing off a salute he departs the room. This business concluded, the Inspector whirls towards the father, “well, don’t worry, we’ve got the ball rolling,” he says amid a storm of casualizing hand-gestures, “everything’s under control.” [ The lesson of resolute Aliette ]The lesson of Aliette might be summarized this way: being where you are makes you very hard to find (the search for her lasts fourteen months before it is “successfully” concluded, changing nothing). As applied to poetry and its marginalization the lesson is in fact rather optimistic; it offers a different kind of “new hope for the disappeared.” In Ron Silliman’s touchstone 1988 essay on “Canons and Institutions,” “public canons” are said to “disempower readers and disappear poets. They are conscious acts of violence” (153). I do not dispute this claim, having all too often seen direct evidence of its validity. I merely want to point out the way bureaucracies perform the task Auden wanted to ascribe to poetry: to make nothing happen. Aliette’s vividly intractable and visibly non-pathological response to being disappeared, her subsistence through it, is what I look to here. I am Still Here.

|

|

|

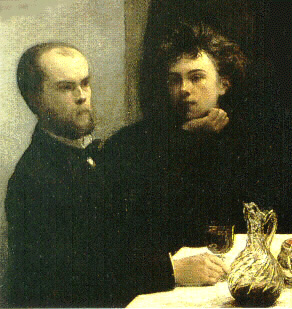

Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud (at right, chin on hand), detail from Henri Fantin-Latour, Un coin de table, 1872, painted a year after the events of the Paris Commune. The subjects were surprised to stumble across the painting in an exhibition of French art in London not long after they had sat for it. Ross tells us that Rimbaud’s later poetry is marked by a distinct proliferation of geographic terms and proper names: poles and climates, countries, continents and cities — a kind of charting of social movements in geographic terms. A vast geography of mass displacements, movements of populations and human emigrations dominates not only Une Saison en Enfer, but a large number of the Illuminations as well.... Rimbaud’s poetry — and Commune culture in general — seemed to me to collapse or render artificial such a division between the psychoanalytic and the social ... [cutting against the] widespread notion that there exists a social production of reality on the one hand, and a desiring production that is mere fantasy on the other. (The Emergence of Social Space 76) As I read Wallace Fowlie’s translation of this poem, I’ll point out to you the places where one lexical index of totality — the word “tout” — occurs in the French: What does it matter for us, my heart, the sheets of blood What subsists after the terrible political sublimities pass, after all that is solid has melted into air — and then congealed anew, order reassembled, reconvened — is just this intractably unsublime kernel utterance: “I am here; I am still / always here.” Is this subsistence necessarily a mode of resignation? The restoration of the I after the phantoms of collectivity, of dark strangers and romantic comrades, are dispelled? We Are Here.

|

|

|

Steve Evans

|

|

J A C K E T # 2 Contents page | “Marginalization” This material is copyright © Steve Evans and

Jacket magazine 1997

|