James Stuart

reviews

Mediated

by Carol Mirakove

91pp. Facory School 2006, Heretical Texts: Vol 2, No 5. 1-60001-049-0 paper

and

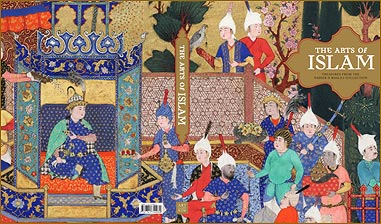

The Arts of Islam: Treasures from the Nasser D Khalili Collection; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, June —September 2007.

This review is about 5 printed pages long. It is copyright © James Stuart and Jacket magazine 2007.

You can read five poems by Carol Mirakove in this issue of Jacket.

1

Perhaps it is not ideal to review a book concerned with “remediating” language alongside an exhibition covering centuries of Islamic Art. But while wandering through the Art Gallery of NSW I could not help but form links between the two.

2

Drawn from the greatest private collection of Islamic art in the world, the Khalili Collection (www.khalili.org), the pieces on display at the Gallery were invariably stunning. Particularly striking were the numerous illuminated Qur’ans that punctuated the exhibition’s seven rooms.

3

In the biblio-centric world of Islam, copies of the Holy Book were objects of particular artistic focus. The non-representational dictates of the religion meant an even greater focus on calligraphy, ornamentation and, indeed, book production in general; folios commissioned by rulers, nobles and moneyed classes cast a shadow across the concurrent achievements of Europe’s medieval illuminated manuscripts.

paragraph 4

A single volume Qur’an from Shiraz, Iran, c. 1525-1550 AD exemplified this as much as any other: its opaque watercolour borders were seething complexes of organic patterns; the gold script, laced delicately over a dense background, exemplified the sacred nature of the Qur’an’s language and the pious prestige that would no doubt have been associated with its owner.

5

To return home and pick up the cheaply produced and rather floppy paperback Mediated was thus a disappointment. Admittedly, we are not comparing like with like; these Qur’ans were incredibly costly objects: the paper and vellum required alone would have been prohibitively expensive for most. Commissioned artisans would have worked for weeks, months, even years, just to create a single folio for a single client.

6

By contrast, these days you can combine a manuscript and a crash-course in desktop publishing with a few dollars and a commercial printer. The result more often than not is a book, one to take its place alongside all other books. However, I refuse to believe that small budgets are cause for poor production standards. Constraints are the boundaries within which one must excel.

7

Deriding a poetry book’s production standards might be unfair but that is no excuse to avoid the obvious: when we review a book of poems, we should be reviewing the book, the poems and the interface between the structuring (physical and narrative) of the two.

8

Such polemic is of course problematic (and not always relevant) but Mirakove does open herself to such analysis by virtue of the company she keeps and the poetic and typographic devices she deploys.

9

In terms of company, the peers who immediately spring to mind are Lisa Jarnot and Johanna Drucker, both of whom fragment standard patterns of language through their work and both of whom are concerned (especially in Drucker’s case) with the spatial and visual qualities of text as it exists on the page (and by extension in the book).

10

Split into four sections–five, if you include the “Community Thanks” at the end where the poet acknowledges her textual sources–Mediated is, as the title suggests, concerned with the mediation of language, history and culture in contemporary America.

11

These conduits include the usual suspects: television, newspapers, pop lyrics, the internet, etc. Interspersed are also samples from (or interpretations of) more personal fields of language: correspondence, monologues and snatches of conversation. All these are recombined into a poetics of subtraction that recalls the work of Jarnot and Drucker.

12

Before diving into the book-at-large, perhaps some elaboration on subtraction is due. Take the following:

13

“murders” “compared with” “during the same time” “gang-related” “enjoyed a steady decline”: numbers dropped. plummeted. under the plan. during “would save lives and [/] 7 million [dollars] a year.”

& so he outspent. there will be children to track, the tally of a bingo: didn’t want/dizzying the ballot count didn’t merely catch. on. own people the most but worn, a real shot & the fete :: happy. formerly of, time and a half, & complicit provides the arrangement, & bows.

- From new generation brings more gangs

14

Here the language of power, of analysis (presumably news reports), is dissected, sampled and recombined. The poetic text that ensues seems to represent an intensified and disjunctive version of the human experience, of the everyday life that flows on from and around such media content and political systems. In both instances uniqueness of vision is achieved by subtracting language, rather than adding it up into new combinations.

15

In other words, Mirakove by and large deducts (in both senses of the word–mathematic and analytical) from the language through which the world is represented to achieve poesis. What are we left with? Sound-bites, poem-bytes, words freed from the topography of Globalism and the free market. Language freed from ready-made sense.

16

While I can’t necessarily relate to Mirakove’s vision–increasing media-literacy means that individuals reactions to mass-mediation become evermore complex; so too the reality of lived experience; so too their ability to filter out the information overload (and besides which capitalism is not all bad)–she does have a point to make and does so with gusto as well as a wry sense of humour.

17

I fucking panic in nature, even at pictures of it. but if everyone could

stop giving their jobs overtime,

even if they didn’t know what they had to,

necessarily

- from traffic was hectic

18

This scathing appraisal of life under late-capitalism (and the America of George W. Bush) will inspire some while others might feel that she could do so more succinctly–take for example that paragon of anti-globalism media, Adbusters wherein is perfected the ability to make a political argument persuasively, concisely and imaginatively. I also have the distinct impression that her method for subverting systemic language might leave her preaching to the converted.

19

Are Heretical Texts the best way to proselytise? Of course proselytising is not necessarily the purpose of art and I would not presume to apply this mode of enquiry to the book at hand–even though the language of incitement, radicalism and revolution (‘Bolivia fought back / Venezuela fought back // they won we could be / winning’) perforate the text. In one instance she even quotes mention the addresses of websites such as impeachbush.tv.

20

I daresay those who commissioned or produced the high-art Qur’ans on display in The Art of Islam might disagree with most notions us modern-day westerners have of art. There were nonetheless parallels to the contemporary arts world within the exhibition.

21

An exquisite scroll-form Qur’an featured unbelievably minute black-ink script, sculpted around Islamic motifs painted in opaque watercolours and edged with gold. Unlike the folios, this scroll was not meant to be read. Instead it would have been worn in a turban, attached to a belt or even displayed as a banner. Here was an artwork interrogating the very nature of the book and its function in social and religious contexts. Such a conceptual framework for the book resurfaces boldly in the 20th century and the world of the artist’s book.

22

The definitions for an “artist’s book” are many and varied. Invariably they hark back to an endeavour to question a book’s “bookishness”–the formal properties that comprise it as a book-object. Mirokave ostensibly asks some of these questions through the poetic tactics she deploys on the page–though it is not feasible to categorise Mediated as an artist’s book in any way (and I imagine this was never the author or the publisher’s intention).

23

As the book progresses through its four sections–MEDIATED, FUCK THE POLIS, PROPAGANDA and PORNOGRAPHY–so too does the shape of poems on the page and the typographic elements that comprise them. This appears to be a formal response to the changing nature of the textual sources and Mirokave’s response to them.

24

For example, in PROPAGANDA she by and large eschews the pop-music and mass media sources that characterise FUCK THE POLIS. Instead the language becomes more more personal, occasionally elegiac.

25

OUT OF WHERE

YOU ARE NOT

catching

the light

a still from where you were

— from OUT OF WHERE YOU ARE NOT

26

Some of the typography is at best rudimentary and I can only hope that Mirakove seeks to engage with this aspect of the craft in more depth in future collections: if poems are to perform on the page as Perloff suggests, [1] if a literary endeavour is to explicitly enact the visual nature of the written/printed language and disrupt rote perceptual patterns (Mirakove’s avant-garde poetry is obviously seeking to do this), then confidence with both visual and verbal language is required.

27

Mirakove’s writing is confident–there is little doubt about this. Take the final section in the book, PORNOGRAPHY, some extracts from which are featured in this issue of Jacket. Here she condenses her language into a variety of polemical and personal utterances–at times almost lyrical. Interleaved between this printed matter, in an elegant script that I only wish I could emulate, are short, elusive lines. At times these obtusely usurp (reclaim?) scientific language, at others they are distinctly prosaic and personal.

28

While there are some technical and typographic issues–for example the bleed-through of the scanned text’s page-outline–Mirakove is obviously enjoying this newfound relationship to the text–handwritten hypertext, shall we say, or perhaps just annotated poems. So too should the reader: it adds new rhythms and different voices to the book.

29

This derives from the counterpoints between deductive statements like ‘Durability, incorporation may continue indefinitely.’ and more personal and, ultimately more simple, statements such as ‘I remember the resentment of the grocer from whom I stole often’ (from ‘Human Traffic’). The absence of the more didactic elements of previous sections also strengthens this section.

30

For better or for worse, Mediated is a book firmly rooted in the now–in its language, its source material, its poetico-political calls-to-action and its production standards. But if a book and the poems it encloses are to last, then the achievements of Islamic book-art over the ages still have much to teach us.

[1] See Perloff, Marjorie ‘After Free Verse: The New Non-Linear Poetries’, author’s homepage (http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/perloff/free.html), 1998.

James Stuart

James Stuart is a poet, editor/curator and new media artist. He also

co-directs arts and debate night The Salon. His most recent projects

include an e-anthology, The Material Poem (ed): http://www.nongeneric.net/,

and online poem-world The Homeless Gods with Karen Chen:

http://www.thehomelessgods.net/. He is completing a Masters of Creative Arts at the University of Technology, Sydney, centred on poetry as material form.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/stuart-mirakove.shtml