James Sherry reviews

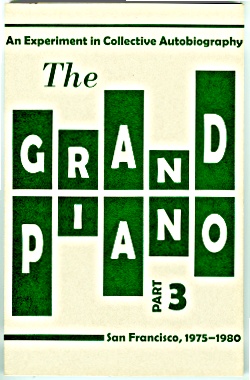

The Grand Piano Project

Part 3

San Francisco, 1975–80

by Bob Perelman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Carla Harryman, Tom Mandel, Ron Silliman, Kit Robinson, Lyn Hejinian, Rae Armantrout, and Ted Pearson.

Paperback, 2007, Mode A, Detroit, $12.95, ISBN 978-0-9790198-2-1. Available via Small Press Distribution at http://www.spdbooks.org/

1

After publishing two prior reviews in Jacket 32 addressing The Grand Piano collaborative series I continue to consider these publications a vital contribution to the collective memory of the poetry of that period. The collaborative series explains one group’s perspective on the history of the progressive poetry movement of the 70s and 80s and as such represent a unique literary biography. The relationship of the individual to the society and its intermediate institutions, such as the Grand Piano readings, is relevant to any thoughtful analysis of the place of poetry writing and production today. GP3 furthers that discussion and delves more deeply into the terms and conditions of the poet-poetry-society puzzle.

2

Part 3 reads mostly about the “I” of that equation: The epigraph to the book is a quotation from Gertrude Stein about the “I” (“being I I am I” is part of the quote to unpack). Steve Benson, the lead-off writer of this volume, goes deeply into the subject both from the perspective of writing like Steve, being Steve, and also in this case being the instigator instead of a responder to existing material or persons, which has been a large part of his persona as a psychologist and in his performance method of listening to texts in headphones while reading or extemporizing other texts. His ability to generate complex results from complex inputs and to keep them coherent is a key skill in collaboration and in the larger contemporary social environment which is the analogy of the collaboration.

paragraph 3

From the point of view of the collaboration Steve sets the height of the bar for the other writers, all of whom address the self or their own writing in their narratives, in the topics they choose in connection with the self, and in the structure they create for those topics. Although I identified the self as a theme for this book, based on reading the epigraph and Steve’s work, most of the writers write about their own work, either around the time of the reading series or more current work. And this identification of the self with the writing helps the reader to understand their works.

4

Coincidentally, a few days after writing this review I had dinner with Kit Robinson and Lyn Hejinian in San Francisco. Over abalone with abalone mushrooms, Lyn mentioned that the common theme of this book was intended to be not the self but the work of the participants. So I decided that the central theme of the review needed to be the difference between the intention of the writer and what the reader gets to see in the final text.

5

I was led to identify the topic as the self by the Stein epigraph and then Steve’s writing about his work as work on himself. (For Benson, as you will see, the self is also the subject of the writing.) For Lyn and Kit the work reads as an extension of self. The intended direction of the book is self criticism of the work of each contributor, not an analysis of the more internal prospects of self, except in the case of Steve where the problem gets more complicated and that distinction turns into a connection.

6

Several important questions hereby get raised. How does the intention of the writers relate to what finally is on the page? Obviously from my reading there was a big gap between what I read and the writers intended. So the question is whether there’s a right way or a variety of interpretations.

7

Then how are the selves which are brought to the work related to the work that results? More specifically why do language poets write about themselves? How valuable is the opacity of unstated purposes in that it forces the reader to read more closely and create their own texts? Clearly there are enough points of view at the beginning of the relationship to fill a book, but I’d suggest as time goes by those multiple points of view are reduced by layers of interpretive writing until a seminal idea or a few core themes are left as the residue of multiple critics over time. This reduction of possibilities over time has a biological counterpart in evolution which I discuss elsewhere.

8

So now in this third episode, we see the doughty Bay Area Language poets as writers and selves interlocked and reviewing their own work. I found out many things on my trip to the Bay Area, not the least of which was how easy a notion of practice can be propounded from parts that seem to interlock, while the intention was elsewhere. And I now question the relationship between intention and the finished work even more than before. This is a topic that I hope to see included in subsequent efforts by the collaborators.

9

Steve himself deplores his self-consciousness, even though his work is himself. The essay is quite difficult, and it must have been hard to write such an open book. “Did I not know how to play?.... What was I seeking in its place? Responsibility? The ability to respond, to integrate reaction and reflection in resolve, in action — I figured maybe it was that.” Remember this was written in the 70s when action was widely considered an ethical question. He haunts bars seeking lovers, but what is his goal? “Is there anyone here who would like to be me? As if my goal were to discover someone to embody this role, about whom I could fantasize afterward.” His progression into relationships with men embodies the traditional poet’s tendency to see the world like or even as the self.

10

But Steve then elevates himself beyond the self-conscious poet. He also finds a social value in identifying the self with others and the world at large: Steve agrees at one level to generalize himself as a version of his friends. “Imagine slipping into one another’s lives for a while — how perplexed and disappointed you would be! Or into one another’s selves — would that have changed our lives?” And with those words the radical value of the collaboration is realized in a narrative about the self. The Grand Piano series takes us beyond Werther, Rameau’s Nephew, and the other self-absorbed figures of the modern age.

11

Along with these advances in defining the self, and maybe contingent too, go some risks about how the self gets extended. This has been the great question about the whole Language movement: does this decentering of the self take away from the immediacy of writing? As a New York member of the group I want to be sensitive to the issue but not paper it over or argue it away. But to state my bias, I find value in the alternatives to Cartesian consciousness and seek to extend them to a planetary level both here and elsewhere.

12

Steve notices this problem emerging in his writing: “Throughout the journal, as so often in the poetry, the human referent is often left unclear.” In other writing I support this lack of definition as part of increasing awareness of the effects of the self on the world and defining collective values. Here it looks like a problem that drives Steve to the edge, because in 1976 there was no longer much awareness of collective action beyond politics, although from the contemporary point of view in 2007, 1976 looks like a commune.

13

Here also the post modern critique is foremost in our minds because of all the writing that has been done by these poets in that mode. But take a look at the possibilities engendered by collective action, a less clearly defined self, and learning the skills to incorporate division of labor as a method toward planetary awareness. I don’t think, however, that vector is much in evidence in GP3 (although it’s mentioned in GP2); so let’s continue with the review.

14

When “the human referent is often left unclear”, what is brought into focus? In this book, as in others in the series, it is the friendship they remember. Ron Silliman extols the value of the face to face relationship beyond the value of the written words, “...I found myself in two very different poetry worlds, one in which I published but communicated largely through the mails, sometimes with people I’d never met, and another characterized by readings (and from 1977 onward, by talks) and face-to-face interactions. The feeling tone of the two worlds was always enormously different and my emotional commitment was always to the latter first.” And it was from energy behind these intense personal relationships that the popularity of the poetry, according to Ron, emanated. “You could tell by the audiences at the Grand Piano that had shot up dramatically beyond what poets were used to seeing, say at the City’s one longstandng reading series at Intersection....”

15

Poets were letting themselves go, linking up, and this was a magnetic force in the poetry world and for the whole counterculture of the period. But there were several other aspects of these privileged relationships. Focus on geography, an idea from Baudelaire / Olsen, became a significant feature when the formative anthology In the American Tree, edited by Silliman, separated the “West Coast” by which he apparently meant his visible friends and the others. Two important downstream effects should be noted:

16

— The desire to proffer a limiting poetics, lowered expectations of the transformative power of poetry on the individual, while expecting poetry to be able to contribute to the larger political process, a collective, if you will, epistemology.

— The focus on ideas and beliefs as extensions of the self.

17

Kit Robinson says, “A community of friends, ‘and the subject, always, poetry,...’.”.... “But the poem itself was suspect.” The self is suspect, the poem is suspect. These people are mighty skeptical, and for me that skepticism was one of the chief values we brought forward in poetry. “We discussed ‘writing’ and experimented with prose. Serial works undid the privileged status of the poem.”

18

A lot of new ideas about the shape and meaning of poems were promoted as in the Legend collaboration among five poets that not coincidently undercut geographical determinism as does the more recent focus on non-locatable blogs by Silliman and other poets. These kinds of geographical boundaries were the residue of NY School personism and did set up a magnetic boundary when collaboration and friendship were being shaped and defined for the extended individual. And it is odd that Silliman promotes this idea since he is and has been so supportive of others’ works no matter where they lived. But in the end it makes sense that you feel closer to people you see regularly and maybe it means no more than that.

19

Other limitations and rules did abound as person was extended in the work. I suggest an analog to a limited coterie of friends or a group of poets of common interest in the limited vocabulary of Kit’s Dolch Stanzas or in my own use of limited vocabularies in listing the 100 most common English words included in my collaboration, Integers, with dancer Nina Weiner, produced and published around the same time. My purpose was to show how meaning was not limited to intentional ordering of words and that as much meaning could be found in limited vocabularies as in universal or so-called complete vocabularies.

20

Kit presents another value: “These self-limiting strategies were designed to open up the work up, to push the limits of the ‘natural,’...” These apparent contradictions and vital alternatives, such as limited lexicons, lead both Kit and Lyn to spend some time on the term “Aporia: an insoluble contradiction or paradox in the text’s meanings.” And it is this contradiction that enabled the existing poetry leadership in both the academy and the counterculture to criticize the poets (and the east coast group that soon absorbed the national interest associated with L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazine) for their focus on ideas. Yet it was this contradiction that acted as an opening for the collaborators. (Note: that Kit and Lyn both address this common topic deepens the collaboration significantly.)

21

Robinson again: “I had the sense that the stranglehold of ideas, whether those of an inflamed self-consciousness or the command-and-control architecture of ideology itself, could be broken, even by the elements of its own composition....” He points to a “kind of balance, a steady state in which the constituents, ‘everyday people,’ recognized themselves to be suspended.” (These statements about politics are more central to my understanding of the group. One could wish for greater use of such visible collaborative mechanisms in the collaboration rather than keeping them invisible and thereby enhancing the value of the text over the method.) He points to “virtuosity” as the “flip side” of the stasis of the society, and I would add the limitation of a coterie of friends. But as we have seen and will see, limitation also provides enhancing possibilities.

22

Virtuosity is abundant in Lyn Hejinian’s poetry extended into ideas. Her version of the self / the work is rendering the history of her own book Writing Is an Aid to Memory. From a reminiscence of an early meeting with her friends to discussions of the relationship between Gertrude Stein and William James to Tristam Shandy to improvisational jazz as well as the unstated but continuous influence of Stendhal’s ego extended into the public sphere, Hejinian’s exegesis of self is indissolubly linked with her ideas and specific texts. “The book is built of phrases...” as the self in the poet’s terms is built elliptically. Development by phrases “had the practical benefit of keeping my attention on phrase units rather than on larger semantic units (the ideas being articulated in the books).”

23

Hejinian sought to recapture some of the bourgeois values from commercial literature. This list of publications objectifies the self and puts it in perspective in a most helpful way. Then he points to the most extraordinary value achieved from their intimacy. Some of this reclaiming and the limited universe of its creation led to political criticism of Language poetry by the left. But Hejinian’s write-up rises above that fray “reclaiming [bourgeois values] for cultural work whose purpose is the very opposite of manipulation.” In the limited environment, the niche, if you will, of Language poetry by the Bay, the aporias they manifested activated consciousness and ironically went beyond politics and its precognition. The introspection we expect in poetry “turned to epistemology. Consciousness could serve as medium for coming-to-know....”

24

Of course I want to question my comfortable conclusions that are so at odds with my rather edgy experience of these events. Members of the group had active conflicts with local persons, resulting in the famed poetry wars in San Francisco based around Poetry Flash. Harryman reports that “when I was a child I threw away my diaries after I filled them up.” This kind of career move was typical of the social instincts of some of the collaborators at that time, but more importantly represents how the group had multiple motives to go beyond the self. I have always thought it was necessary to defend against the screeching antagonism from poets, locked in themselves, to the more open manifestation of our art evidenced in this collaborative biography.

25

And true to form, it’s Silliman who resurrects, reclaims, and clarifies the conditional situation with a brief history of himself based on the timeline of some of the publications that published him in that period. What people said and did does not go in a straight line and to do so in retrospect fails to deliver the sense to the reader. Ron cites a conceptual artist friend who felt frustration that her scene “didn’t have enough terms in common with each other to be able to build on what one another were doing.” That was the method of influence and to this reviewer the main attraction of Language writing in general as the common terms and themes gave rise to a formidable poetry and poetics.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/sherry-piano3.shtml