This piece is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © John Felstiner and Jacket magazine 2007.

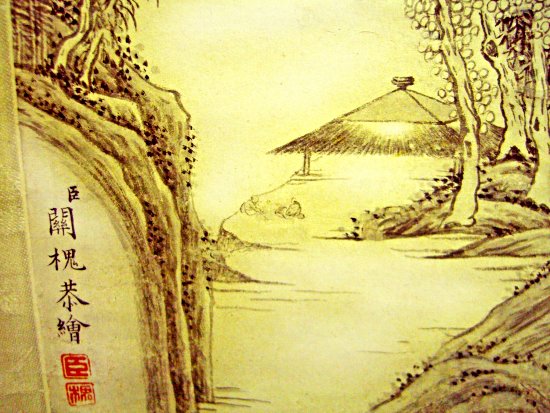

Chinese scroll, image courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum, Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection.

1

When I was eleven or twelve, I went into the Chinese room at the Seattle art museum and saw Chinese landscape paintings; they blew my mind. My shock of recognition was very simple: “It looks just like the Cascades.” The waterfalls, the pines, the clouds, the mist looked a lot like the northwest United States. The Chinese had an eye for the world that I saw as real.

paragraph 2

Washington’s North Cascades mountains never faded for Gary Snyder (1930), wherever his paths between nature and poetry took him: South America and the Persian Gulf as a working seaman, San Francisco and the Beat Movement, the northwest on logging teams, trail crews, fire lookout, Japan for Zen practice and mountain climbing, Reed College and Berkeley studying American Indian anthropology and East Asian languages, California’s Sierra Nevada where he’s lived since 1970.

3

“Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout” opens his first book, Riprap, with a keen sense for what the poet “saw as real”:

4

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies

I cannot remember things I once read

A few friends, but they are in cities.

Drinking cold snow-water from a tin cup

Looking down for miles

Through high still air.

5

Noting what’s present, these “small nouns / Crying faith” (as Oppen put it) take no needless adjectives, and one verb illumines an immense vista, draws us close: “Pitch glows.” No “I” so far — the scene does without oneself.

6

On second hearing, more comes to mind. Everything seems still, but the poet’s at work, fire-watching in high summer. Smoke started this poem, maybe from heat after rain. Pitch glows, so it must be clear, if hazy down below. Then the voice enters, an own person, “I cannot remember.” The solitary seer then dissolves in “Drinking...Looking,” ongoing verbs scrolling across a very present landscape limned in the simplest syllables.

7

Frugality guides this poem. “It’s like backpacking. I don’t want anything that’s unnecessary.” Think of John Muir roaming Yosemite with blanket, bread and cheese. Snyder would do without a stop after “cities,” but his city friends aren’t the ones drinking cold snow-water. The poem ends in silence, clarity, or doesn’t end, as “Looking” drifts “for miles / Through high still air.” These “plain poems,” he said, “run the risk of invisibility.” They do “the work of seeing the world without any prism of language, and to bring that seeing into language.” An arc of tension connects words to the world.

8

All is not blissful mindlessness up in still air. The summer of 1952, Snyder kept a journal at Crater Mountain lookout, 8149 feet: “Really wretched weather for three days now — wind, hail, sleet, snow...hit my head on the lamp, the shutters fall, the radio quits...Outside wind blows, no visibility.” After a week the weather clears, he can see three million acres of forest. On 28 July his “pressing need” is “to look within and adjust the mechanism of perception.” That same day sees “A dead sharp-shinned hawk, blown by the wind against the lookout.” So man’s lookout on the world can damage things. “To write poetry of nature,” Snyder then says, “to articulate the vision,” means a conflict between one thing and the other:

9

(reject the human; but the tension of

human events, brutal and tragic, against

a non-human background? Like Jeffers?)

10

Thinking of Robinson Jeffers perched in Hawk Tower on the California coast prompts one last entry on 28 July: “Pair of eagles soaring over Devil’s Creek canyon.”

11

Like Keats at Ambleside Falls thinking of Milton’s Eden, Snyder wears a poet’s knapsack. He amused the grizzled firewatchers by hauling in Zen Buddhist readings to his lookout along with a sack of brown rice, a gallon of soy sauce, Japanese green tea, and Chinese calligraphy brushes. In 1953 he went back from San Francisco to Sourdough Mountain lookout, above the Skagit River, where his journal sounds like an ancient scroll painting: “wind blowing mist over the edge of the ridge, or out onto the snowfield... Clumps of trees fading into a darker and darker gray.” He stuffs the stove “with twisted pitchy Alpine fir limbs” and in mid-August comes on William Blake’s proverb: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

Chinese scroll, detail, lower left. Image courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum, Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection.

12

An 18th-century Chinese scroll, maybe the source for Snyder’s shock of recognition and much like the view from his Cascades lookout, has been in Seattle’s Asian Art Museum since he was a boy. Its mountains, pines, and waterfalls recede upwards into clouds and mist — Snyder has thanked Chinese landscape painters for their “vision of earth surface as organism, in which water, cloud, rock, and plant growth all stream through each other.” Near the base of this scroll, though, what the eye can hardly spot are two figures sitting outside an open pavilion, doubtless sipping tea and talking philosophy like the “Chinamen” in Yeats’s “Lapis Lazuli.” Scarcely visible, they prove the question of human presence in wild nature. We’re present alright — not central like Blake, but a conscious, active part of it all.

13

Not mindlessness but Zen emptiness, alert, attentive, clear of clutter and anxiety, opens perception for Snyder: glowing fir-cones, new flies swarming, fresh water chilling a tin cup. Call it mindfulness, immersion until the surrounding wildness finds a kindred ecosystem in us, in the cup of our own wild mind. “Shall I not have intelligence with the earth?,” Thoreau asks in Walden, which Snyder was reading in 1953. His journal for 14 August says, “Don’t be a mountaineer, be a mountain,” though he hadn’t yet come across Aldo Leopold’s land ethic in Sand County Almanac (1949), “Thinking Like a Mountain.”

14

That autumn Snyder met Kenneth Rexroth, a generation older and long since primed for California’s high country by the classical Chinese and Japanese poets. Holding salons at his home, Rexroth quickly spotted a poet in the making. Snyder, pursuing his way within a tradition, began studying East Asian Languages at Berkeley and translated the Cold Mountain poems of Han-shan, a 7th-century T’ang Dynasty Chinese hermit who smacks of the American Indian Coyote trickster, scratching poems on bamboo, wood, stones, cliffs, house walls.

15

Cold Mountain has many hidden wonders,

People who climb here are always getting scared.

When the moon shines, water sparkles clear

When wind blows, grass swishes and rattles.

On the bare plum, flowers of snow

On the dead stump, leaves of mist.

At the touch of rain it all turns fresh and live

At the wrong season you can’t ford the creeks.

16

A wry turn at the outset, then a clear-minded sense of time and place, “When...On...At,” breathing that way of seeing and saying things into 20th-century American poetry.

17

Soon it became plain: Snyder must enter upon Zen Buddhism in Japan. He lived there many years between 1956 and 1968. “Kyoto: March,” from Riprap, goes this way:

18

A few light flakes of snow

Fall in the feeble sun;

Birds sing in the cold,

A warbler by the wall. The plum

Buds tight and chill soon bloom.

The moon begins first

Fourth, a faint slice west

At nightfall. Jupiter half-way

High at the end of night-

Meditation. The dove cry

Twangs like a bow.

At dawn Mt. Hiei dusted white

On top; in the clear air

Folds of all the gullied green

Hills around the town are sharp,

Breath stings.

19

Light flakes, weak sun, birdsong, plum buds — What of it? What’s the point? — new moon, dove cry, dawn snow dusting the peak, clear air sharpening the gullied green. But maybe they’re the point: clean nouns, fresh verbs, beginnings, marked by breath and meditation. So much depends — in college he’d heard Williams read — upon seeing and saying. No ideas but in things.

20

Riprap was printed in Kyoto, 500 copies on fine paper folded and sewn Japanese-style. Snyder glosses his title word: “a cobble of stone laid on steep slick rock to make a trail for horses in the mountains.” The title poem begins:

21

Lay down these words

Before your mind like rocks.

placed solid, by hands

In choice of place, set

Before the body of the mind

in space and time:

Solidity of bark, leaf, or wall

riprap of things...

22

Frost feels the sound of sense in an ax-helve’s lines “native to the grain,” Bishop spots “tiny cows, / two brushstrokes each” in a painting, Celan finds his “unannullable witness” “Deep / in the time-crevasse, / by / honeycomb ice,” Hughes tracks a fox across “dark snow” till the poem is done. So in Riprap, “each rock a word / a creek-washed stone” lays down mountain trail. In Snyder’s economy and ecology, a poem makes its way through steep terrain using native materials, fitting words. He says “Lay down these words...like rocks,” yet something deeper than likeness drives him. Being physically, psychically part of nature, as we all are, he wants the same source of energy and design in his poems as he finds in the world they articulate.

23

At a volcano on a small Japanese island, looking down to “red molten lava in a little bubbly pond” in 1967 at the new moon, Snyder married Masa Uehara, his third wife, and when a son was born, they settled in the States. There all the segments of his life and work made up a whole: rural youth, avid hiker-climber, redneck (his word) logger, seaman, and firewatcher, Amerindian anthropologist, Zen Buddhist adept, erotic lyricist, teacher, traveler, translator, Beatster in Jack Kerouac’s Dharma Bums, social critic, environmental guru and activist, essayist, speaker, interviewee, inheritor of Hopkins, Whitman, Thoreau, Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Williams, Lawrence’s Birds, Beasts and Flowers, after Jeffers and Rexroth the American West’s leading 20th-century poet.

24

But “America” and our carved-out “States” don’t identify his native country for Gary Snyder. What does is “Turtle Island — the old/new name for the continent, based on many creation myths of the people who have been living here for millennia,” myths of the earth sustained on the back of a great turtle. His Turtle Island (1974) starts with a section called “Manzanita,” the tough Pacific Coast shrub/tree with red-brown crooked glossy peeling branches, green leaves, early-blooming pinkish-white flowers favored by hummingbirds, and “little-apple” fruit eaten by bear, coyote, deer.

25

Published first as a chapbook in the Sixties enclave of Bolinas, California, this section opens with “Anasazi” — late-Paleolithic Southwest pueblo people, ancestors to the Hopi, who left grand desert dwellings and petroglyphs, including the humpback flute-playing fertility figure Kokopelli or Kokopilau much loved by Snyder among others:

26

Anasazi,

Anasazi,

tucked up in clefts in the cliffs

growing strict fields of corn and beans

sinking deeper and deeper in earth

up to your hips in Gods

your head all turned to eagle-down

& lightning for knees and elbows

your eyes full of pollen

the smell of bats.

the flavor of sandstone

grit on the tongue.

women

birthing

at the foot of ladders in the dark.

trickling streams in hidden canyons

under the cold rolling desert

corn-basket wide-eyed

red baby

rock lip home,

Anasazi

27

The way of the words makes an ongoing whole of Anasazi dwellings & cornfields & religion & animals & mothers & children & watershed desert homeland. Meanwhile “growing...sinking...birthing...trickling” hold the Anasazi people in their own present, or maybe caught back then — which poses a challenge, if we want their ways open to us now. Today we see a far-removed people, each in their “energy-pathways that sustain life” (Snyder’s note). “Hark again to those roots, to see our ancient solidarity, and then to the work of being together on Turtle Island.”

28

Being together. Snyder recalls just one thing Williams said during his 1950 visit to Reed College: “Art is about conviviality” — “And that stuck in my mind!” Living together joyously. We can hear and see as much when Snyder performs his poems, moving from a deep voice to a tenor, varying speed, volume, tone, intensity, emphasis, with sudden enunciations, hands gesturing, fingers pointing, often with a comical shrug, facial turns and shakes and glances. Poetry has got to jog us together with other peoples, our own, and other species.

29

During the Sixties a fresh urgency moved him, before Rachel Carson’s wake-up call The Silent Spring: “As poet I hold the most archaic values on earth. They go back to the late Paleolithic: the fertility of the soil, the magic of animals...the common work of the tribe. I try to hold both history and wilderness in mind, that my poems may approach the true measure of things and stand against the unbalance and ignorance of our times.”

30

Moving his family in 1970 to a hundred acres in the Sierra Nevada foothills, Snyder began shaping a life by those values — not trapping and hunting for his food, like John Haines in Alaska, but building a home among like-minded neighbors, treating the forest sustainably, working locally for good governmental practices. That year he spoke out: “I wish to bring a voice from the wilderness, my constituency. I wish to be a spokesman for a realm that is not usually represented either in intellectual chambers or in the chambers of government.” To be an “ecological conscience.”

31

Turtle Island sites one poem near his new home, “By Frazier Creek Falls,” where as in the scrolls there’s room for dimming vistas as well as glittering, rustling detail and sometimes a tacit, a heartening human presence:

32

Standing up on lifted, folded rock

looking out and down —

The creek falls to a far valley.

hills beyond that

facing, half-forested, dry

— clear sky

strong wind in the

stiff glittering needle clusters

of the pine — their brown

round trunk bodies

straight, still;

rustling trembling limbs and twigs

listen

This living flowing land

is all there is, forever

We are it

it sings through us — ...

33

He would never claim, like Blake, “Where man is not, nature is barren.” Humans take part in wild nature, our language springs from and plays off it.

34

All his life Gary Snyder has pledged himself to holding both wilderness and history in mind. Danger on Peaks (2004) arcs back to August 1945, when he climbed Mount St. Helens in southern Washington. The next day came news of Hiroshima, and a scientist saying “nothing will grow there again for seventy years.” “I swore a vow to myself, something like, ‘By the purity and beauty and permanence of Mount St. Helens, I will fight against this cruel destructive power and those who would seek to use it, for all my life.’” The 15-year-old took a photo, looking across the calm reflective expanse of Spirit Lake at a mountain that would later erupt with five hundred times the force of the atomic bomb.

John Felstiner

John Felstiner wrote The Lies of Art: Max Beerbohm’s Parody and Caricature (1972), Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu (1980), which won the Commonwealth Club Gold Medal, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew (1995), which won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism and was a NBCC Finalist, Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan (2001), which won ATA, MLA, and PEN prizes, and co-edited Jewish American Literature: A Norton Anthology (2001). His Neruda and Celan translations won British Comparative Literature Association prizes, and he’s a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has been at Stanford since 1965, and taught at the University of Chile, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Yale. Last spring a brace of essays on translation came out in TWO LINES and Translation Review. His upcoming book, So Much Depends, concerns poetry and environmental urgency. Essay-chapters have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Poetry Today, Parthenon West Review, International Studies in Literature and Environment, Iowa Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Weekly Standard, and six are running in American Poetry Review during 2007. A version of his essay on Gary Snyder appeared in The Seattle Review, July 2007.

In Jacket 31 you can read ‘The Lure of the God: Robert Duncan on Translating Rilke’ by John Felstiner and David Goldstein.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/felstiner-snyder.shtml