You can read 70 printed pages of poetry selected from Murat Nemet-Nejat’s anthology in this issue of Jacket.

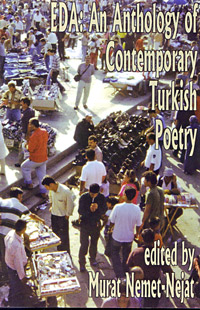

This piece is about 30 printed pages long. It is copyright © Murat Nemet-Nejat and the individual contributors and Jacket magazine 2007. Jacket is grateful for permission to republish this material. Unless otherwise indicated, all the following pieces are from this printed book: «Eda: A Contemporary Anthology of 20th Century Turkish Poetry» edited by Murat Nemet-Nejat. 367 pp., 2004. US$27.95. 1-58498-034-6 paper; Talisman House, P.O. Box 3157, Jersey City, New Jersey, 07303-3157, U.S.A. Email: TALISMANED[ât]aol.com

Buy the book here!

Contents: Essays (click on the title to be taken to the essay)

The 1990s, the Poetry of Motion

from “Ideas Towards a Theory of Translation in Eda”

The Double Vision of Translation

Herman Melville, Charles Olson and Moby Dick as a Sufi Poem, a Footnote

from Souljam: küçük İskender’s Subjectivity

Through Western Eyes

I.

paragraph 1

...

It has often been said that the natives

will only teach foreigners a fake, degraded language,

a mock system of signs

parodying the real language.

It has also been said that the natives

don’t know their own language,

and must mimic the phony languages of foreigners,

to make sense out of their lives.

— Linh Dinh, “Vocab Lab,” American Tatts

II.

2

If one wants to grasp the underlying principle of 20th century Turkish poetry in one stroke, it is that it brings animism into the middle of our global universe. Everything in that poetry becomes relatively clear from that perspective. Not only trees or animals, but in this poetry colors, objects, things, natural processes are in dialogue with each other, weaving their endless patterns. Eda is the structure of that pattern, the mesh of linguistic and geographic coordinates which go to its creation. Not the individual, but objects, colors, things are at the center of this endless transformation, the ego attached to it only tangentially, a detail, suffering and ecstatic. It is this peripheral relationship of consciousness to wider natural forces — subjective and objective, visceral and abstract — which gives Turkish poetry its stunning originality.

III.

3

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Introduction to Eda: An Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry: ‘The Idea Of a Book.’ [43]

4

As much as a collection of translations of poems and essays, this book is a translation of a language. Due to the fortuitous convergence of historical, linguistic and geographic factors, in the 20th century — from the creation of the Turkish Republic in the 1920’s to the 1990’s when Istanbul/Constantinople/Byzantium turned from a jewel-like city of contrasts of under a million to a city of twelve million — Turkey created a body of poetry unique in the 20th century, with its own poetics, world view and idiosyncratic sensibility. What is more these qualities are intimately related to the nature of Turkish as a language — its strengths and its defining limits. As historical changes occurred, the language in this poetry responded to them, flowered, changed; but always remaining a continuum, a psychic essence, a dialectic which is an arabesque. It is this silent melody of the mind — the cadence of its total allure — which this collection tries to translate. While every effort has been made to create the individual music of each poem and poet, none can really be understood without responding to the movement running through them, through Turkish in the 20th century. I call this essence eda, each poet, poem being a specific case of Eda, unique stations in the progress of the Turkish soul, language.

5

In “The Task of the Translator” Walter Benjamin says that what gives a language “translatability” is its distance from the host language. Eda is this distance.

6

The otherness of eda has three aspects, thematic, linguistic and metaphysical, together forming its core, essence:

7

a) Thematic: Istanbul, Mistress — Constantinople, Ward of The Virgin Mary

8

Istanbul, the city of unspeakable beauty; the city of stench, crooked streets, endless vice; the long coveted prize of the Islamic Ottoman Empire; the vulnerable, beloved, cherished spiritual center of Eastern Christianity; the site of the rational, tent-like simplicity of Turkish Imperial architecture [44]; the awesome interior space of the Hagia Sofia; the European and Asian city; the city of crossings and bridges and double crosses; the city gorgeous to the eye, even more beautiful in its secrets; the city of spiritual yearning and impulse murder; the city of disco bars whose basement forms a Byzantine palace [45]; the city of violet water; the city of trysts; the city where place names gain fetishistic value; the city where life and history are cheap, and they are both everywhere.

9

The paradoxical nature of Istanbul is the obsessive reference point of 20th century Turkish poetry. Almost no poem is untouched by it — its shape, its street names, its people, objects and activities, its geographic and historical locus. As the city evolves, the poetry responds, trying to re-organize, make sense of the changes. This interplay between city and language resonates spiritually, erotically, politically, philosophically.

10

b) Linguistic: “am am a sea vermin, so human goose the block of ice on which i fly is [souljam ]”

11

Turkish is an agglutinative language, that is to say, declensions occur inside the words as suffixes. Words need not be attached to either end of prepositions to spell out relationships, as in English. This quality gives Turkish total syntactical flexibility. Words in a sentence can be arranged in any permutable order, each sounding natural.

12

The underlying syntactical principle is not logic, but emphasis: a movement of the speaker’s or writer’s affections. Thinking, speaking in Turkish is a peculiarly visceral activity, a record of thought emerging. The nearer the word is to the verb in a sentence, which itself has no fixed place in the sentence, the more emphasis it has. This ability to stress or unstress — not sounds or syllables; Turkish is syllabically unaccented — but words (thought as value-infested proximity) gives Turkish a unique capability for nuance, for a peculiar kind of intuitive thought.

13

Eda is the play of ideas through the body of Turkish. Not only is it the poetics of Turkish poetry in 20th century, it is the extension of the language itself, the flowering of its inherent potentials as a language.

14

The otherness of Eda is the distance which separates Turkish from English. English is an amazingly plastic language in terms of analytic thought, must spell out the relations between objects, between thoughts. A word like “from” or “to” predetermines the words which must precede and follow it. English permits a thought to be sayable only after being analyzed, socialized, objectified. This is the mystery of its rigid syntax after the Enlightenment. It resists, syntactically ostracizes — by being unnatural — pre-analytic thought, encouraging, recording the objective, tradition, socialized thought.

15

Eda is the alien other. What is this alien ghost, the way of moving and perceiving which must enter and possess English? It is Sufism, the Asiatic mode of perception which contains an intense subjectivity at its center. The pre-Islamic origins of Sufism is in Central Asian Shamanism. Turkish was the language of that area; its grammar is the quintessential Sufi language.

16

Before going any further, Turkish has no gender distinctions, either he or she or it. Though one may assume that the specificity of the situation would make it clear, this is not quite so. In Sufism (and the poetry of eda) the distinction (any distinction) does not truly exist; “it” (a bird, for example) is a link between the divine (he/she/it) and human (he/she), with the constant possibility of movement among them. Pronouns are fungible, conceptionally their references unstable. Suppose an English sentence where the pronoun (so gender and reference specific) shifts in the middle, lopsiding the syntactical balance.

17

[c) Metaphysical: Sufi Contradictions and Arcs of Ascent and Descent

18

In its pre-Islamic origins, Sufism unifies contradictions, more precisely, perceives, intuits experience before its splits into opposites. The Islam introduces a mathematical language into this intuition. God, the lover, and the human lover are one, turning to and into each other, through a process both violent and loving.

19

Arcs of Descent and Ascent describe this process, movements from the unity of God to phenomenal multiplicity and the reverse, from multiplicity to unity. These movements are simultaneous, not sequential — two aspects of one divine essence. The supreme moment in Sufism is the sudden shift in perception when a state (in its multiple senses) of exile, of accelerating multiplicity and distance, is experienced as yearning, a re-unifying movement, yearning, towards home, God. The shift is in perception, that is, in the mind. Everything, every object in existence, particularly physical love, move towards this moment. That is the radical subjectivity — love as objective subjectivity — at the heart of Sufism.

20

Sufism embodied in eda is different from Mevlana Jalaloddin Rumi’s, with which the West is more familiar. Rumi’s supreme process is ecstasy, reached through wine and dancing. On a linguistic level God and the speaker remain distinct, “You” and “I.” Sufi union with God is expressed philosophically, metaphorically, harmonically.

21

In the Turkish tradition the supreme Sufi act is weeping, the dissolution of the individual ego by suffering through love, loss, the liquid of tears. What is ecstatic in eda involves a blurring of identities, in pain, at the same time, moving from object to object, unifying them in a mental movement of yearning, dance of dispossession. Wine has to be bought; tears are for free. No gendered pronouns, no stable word order, Turkish is a tongue of radical melancholia.

22

Distinctions dissolve into union. Here is the paradox of simultaneity in the arcs of descent and ascent. A waking state enters another’s dream, and vice versa, creating a continuum. The objective becomes subjective. Physical desire ends in spiritual satiation. Weakness is also an expression of power. Pain is also pleasure. The Istanbul harbor with its crossing boats is a site of extreme beauty, paradise, and Styx, a separator and joiner of Europe and Asia, etc. The central sphere in Eda is the moon, the prevailing light, moonlight: visible dark.

23

In its essence, this poetry has no metaphors (but creates spiritual stations of which Istanbul is the center) because no distinctions. Every image is a station, a physical sight in a spiritual progress of reincarnations, of yearning. Images and thoughts collapse towards each other, in love: “The rough man entered the lover’s garden/It is woods now, my beautiful one, it is woods,” says the 16th century poet Pir Sultan Abdal. What is the garden? The lover’s pubic hair or a divine garden, “it”? Who is the “rough man”? The speaker, the speaker’s lover or a third? To whom, by whom are the words uttered? In Turkish Sufism consciousness (love) is not a matter of “You” and “I”; but a triangle: you, I and he/she/It.

24

Here lies perhaps the crucial role of Istanbul in eda. Located on two continents, precious both to Christianity and Islam, with its endlessly contradictory nature, Istanbul becomes a site for a series of superimpositions.

25

In the essay, “What children Say,’ Giles Deleuze states:

26

... a milieu is made up of qualities, substances, powers, and events: the street, for example, with its material (paving stones), its noises (the cries of merchants), its animals (harnessed horses) or its dramas (a horse slips, a horse falls down, a horse is beaten...). The trajectory merges not only with the subjectivity of those who travel through a milieu, but also with the subjectivity of the milieu itself [italics my own], insofar as it is reflected in those who travel through it. [46]

27

Istanbul is that milieu. Eda is the trajectory, poetics of a trip on a map. Sufism is its fusion of objectivity and subjectivity, a convergence of psychic time with history — the history of a city in 20th century and of the soul of the folks passing though it.

Back to Contents (top of page)

28

I, in my room overlooking the seashore,

Not looking out of the window,

Know that the boats sailing out in the sea

Go loaded with watermelons. (Orhan Veli)

29

The first work in this anthology was first published in 1921, the last in 1997. During this period Turkish poetry underwent three major transformations. The first occurred between 1921, the publication of Ahmet Haşım’s poem “That Space” (“O Belde”) in his book Lake Hours (Göl Saatleri) and 1950, the year Orhan Veli died. During this period, for the first time in almost four hundred years, since the Azeri Turkish poet Fuzuli’s Leila and Majnun, agglutidunal Turkish became a written literary language. There are four central poets in this period, Ahmet Haşım, Yahya Kemal Beyatlı, Nazım Hikmet and Orhan Veli. Seemingly very different from each other, they all write in spoken Turkish and, together, they establish the backbone of Eda in Turkish poetry.

30

Haşım and Beyatli appear closer to the earlier Ottoman poetry in their sound (occasional use of the gazel form and rhymes) and vocabulary (use of Persian and Arabic words). But the cadence of their language is Turkish and each brings something new and essential to the language.

31

Haşım brings the shy, slightly feminine, sinuous, melancholy, linguistically self-conscious movement to Turkish poetry. The inherent potential in Eda for yearning, long sentences, in the flight to make thought connections which sometimes tease with falling apart, originates from him.

32

Beyatli’s poetry sounds even closer to Ottoman poetry. The conventional view of him is that he is a formalist recreating in modern Turkish the classical sound of Ottoman forms — a poetry of Ottoman music. I think the view misses its importance. A philosophical pursuit runs through Beyatli’s formal sound and rhyme patterns. It is to obliterate conceptual splits of time (between past and present) and consciousness (between waking and sleeping states) into a continuum. This conceptual shift, the impulse to cross over, absent in Ottoman poetry, is an integral part of Eda.

33

The pursuit undercuts, disrupts Beyatli’s poetry of “pure music” because the Ottoman gazel, of rhymed distinct units, does not contain Beyatli’s anti-formal sense of reality. Consequently, in my view, there is an an instability pushing against, potentially breaking through and toppling, discrete rhymed couplets. Sidney Wade’s exquisite Night in the anthology translates Beyatli’s “pure music” as well as one can. “That Summer” and “Reunion” try to touch the inherent instability of thought pushing through the sound structure.

34

Nazım Hikmet wrote his major poetry in the 1930’s and 1940’s while he was in jail for Communist subversion not very far from Istanbul. The poem/letters to his wife from jail are full of yearning for his wife, for Istanbul, for a better future for mankind, reminiscent of eda. Hikmet also started writing Human Landscapes From My Country (Memleketimden İnsan Manzaraları), possibly his central work, in the 1930’s in jail. This is an epic the poet Ece Ayhan calls a “cinematic work, “which starts with the Turkish War of Independence and covers a range of Anatolian characters. In this poem Hikmet uses the Anatolian landscape as a space of psychic movement (at moments, language as a river) very much the way Istanbul is used in eda.

35

Starting with 835 Lines (835 Satır) in 1929, any Ottoman echo in Hikmet’s poetry disappears. Hikmet replaces old structures with two things: the rhythms, cadences of Anatolian folk poetry and the Russian poet Mayakovski’s darting, staggered, futurist lines. These two elements remain constants — partly visual constants — in Hikmet’s poetry. The darting line fragments often gain a sinuous melancholy, peculiarly Turkish.

36

Orhan Veli, who wrote his poetry also in the late 1930’s and 1940’s, represents the culmination of the first stage of eda. As an agglitudinal language the center of gravity of Turkish is not in words, but the cadences among them; the aura that movement creates. In his introduction to the manifesto/poetry-book Strange (Garip), Veli says: “I wish it were possible to dump language itself”(trans. By Talât Saİt Halman). Veli writes a minimalist poetry stripped of metaphors; what remains is pure cadence, its space. Poems which seem to be made of absolute inessentials are unforgettable. In him the link between eda and the rhythms of conversational Turkish becomes absolute.

37

Veli is the lightning rod of Turkish poetry. Every ensuing movement starts with an attack on him. For instance, Cemal Süreya partly starts the Second New movement (the First being Veli’s and his friends’ Strange) in an essay entitled “Orhan Veli’s Mistake,” attacking Veli’s limitations, asking for a poetry penetrating secrets. Here is what he says about Veli: “No line, no meter, no music, no image, no beauty, no rhymes, no metaphysics, no drama.” Ironically, towards the end of his life, Süreya wrote powerful poems very reminiscent of Veli. Another Second New poet, Ece Ayhan, calls Veli a “watercolor poet”; but towards the end of the essay he mentions Veli’s “portability,” calling the poems folk songs. Another group calls Veli a “state” poet, suggesting that the popularity of Veli was pushed by the government to deflect from Hikmet’s communist poetry. Veli keeps being read and re-read.

38

Before going on any further, one needs to mention a group of poems whose significance is often overlooked. From the 1930’s into the 1950’s some poets wrote in syllabic meters, often rhymed and derived from folk poetry. This work constitutes a distinct genre which I call arabesque. Arabesque has two meanings. First, it is the name of a popular musical genre started in the 1960’s, becoming prevalent in the 1970’s and 1980’s, when a huge influx of Anatolian population turned Istanbul from one and a half million into a metropolis of twelve million. Arabesque is the music of truck, bus and taxi drivers, of waiters, of laborers, of street venders, etc., most of them Anatolian Muslims.

39

Arabesque poems project a religious consciousness which, nevertheless, embraces love as a profane, obsessive, rebellious act. Faruk Nafız Çamlibel’s “The Escaper” and Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu’s “Black Mulberry” are examples of it. The poems often have a street feel to them, similar to the American blues. Arabesque is the genre through which the Anatolian consciousness, its urban alienation, integrates itself into Eda. In Cahıt Külebi’s poems, for example, the speaker is an Anatolian peasant talking to another Anatolian (often, a lover), Istanbul implicitly there, indirectly referred to as an alien third.

40

Most arabesque poems were written by the 1950’s, before the arabesque had emerged as a musical genre. This is startling because Istanbul was still a discrete, relatively small city. The poems prophetically anticipate the Anatolian flux into the city — pre-writing its consciousness — sing of a future to come. This premonitive response is the critical importance of the genre, sustaining eda’s intimate contact with the Turkish population.

41

The second meaning of arabesque is the elaborate, abstract decoration often inside mosques. An admirer of Beyatli, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar writes arabesques in that sense, exquisitely modulated poems of “pure” Sufi music.

42

Perhaps, the most important arabesque poet is Nafiz Fazıl Kısaürek. Using both syllabic folk and Ottoman gazel forms, his poetry is obsessive, profane and religious, a poetry of the Sufi arc of descent. The Second New poet Ece Ayhan considers his poetry clunky, full of “high-school/teen-age” emotions. I think the baroque “clunkiness” is part of its arabesque identity, integral to its unforgettable power. Kısakürek’s pursuit of lower depths, towards a remote illumination, makes him one of the precursors of a 1990’s poem like küçük İskender’s souljam (cangüncem).

* *

43

She didn’t fetch her hair along,

Kept it on the dresser, full of despair;

But her hair fell through the unlit cracks,

I undid her drawers

I drowned myself in her hair. (Cemal Süreya)

44

The Second New represents the second stage in eda. Officially, it starts in the 1960’s with the magazine Papyrus (Papirüs), edited by Cemal Süreya, in which he published new poets, including their critical essays. But the poems which start The Second New, the ones inside Cemal Süreya’s first book Pigeon English (Üvercinka) and Ece Ayhan’s Miss Kinar’s Waters (Kınar Hanımın Denizleri) were written in the 1950’s, by two young men in their twenties.

45

Though others belong to it, the central poets of The Second New are Cemal Süreya, Ece Ayhan and İlhan Berk. Their influence is sequential and forms stages in the development of Eda, paralleling changes in the perceptions of Istanbul as a city.

46

The overweening thrust of The Second New is expanding consciousness, in depth (revealing secrets) and range of emotions (expanding poetic styles). That’s why The Second New starts with a misreading (deliberate or not, maybe necessary) of Orhan Veli. Pigeon English, Süreya’s first book, is a series of lyrics of seduction from the male point of view. What is amazing about them is the power dimension of the eroticism — love as a stripping of both the body and mystery. In spectacular image combinations, the poems implicate, seduce the reader into the act — keeping him or her grasping/gasping for objectivity. These image combinations are the great contribution of Süreya to Turkish poetry. They release the sado-masochistic, subversive side of Sufism into contemporary Turkish.

47

A story underlies Üvercinka. In its middle a woman rejects the speaker. By this, the power angle of the poems reverses to one of grief. Though never completely suppressing the other side, this changed point of view predominates Süreya’s later poetry. In Your Country, for example, is a poem of dissolution through loss. In that respect, Süreya’s development is within the central Sufi narrative of Fuzuli’s Leila and Majnun, physical love changing into spiritual love. At the end of his life Süreya wrote beautiful, simple poems, the last one of which is, “After 12 P.M./All drinks/Are wine,” lines of total acceptance, referring back to Ahmet Haşım and his predecessor Hafiz. The beauty of these poems are reminiscent of Orhan Veli. Süreya comes full circle back to the Turkish poet he starts his poetic movement by attacking

48

Ece Ayhan had to self-publish his first book, Miss Kinar’s Waters. Instead of like Süreya’s exuding a seductive masculine eroticism, Ayhan’s book is opaque, personal, trying to hide, as much as to reveal. Miss Kinar’s Waters also has a story buried in it, that of a sister’s suicide (possibly, from being seduced).and the grief surrounding such an event. All the poems are from the point of view of the victim, the weak, the powerless, including seduced children turned hustlers; many are gay. Even when the poem is from the angle of the seducer, e.g. in “Wall Street” (“Kambiyo”), the tone is elegiac. Eroticism is tinged with suppressed rage, which in flashes pierces through as implicit commentary. These flashes weave a melody whose emotional tone is lucid, transparent; but whose meaning eludes us, is veiled.

49

Miss Kinar’s Waters and Ece Ayhan’s ensuing two works, A Blind Cat Black (Bakışsız Bir Kedi Kara) and Orthodoxies (Ortodoksluklar), open up the suppressed, unofficial — but inescapably there — strata of the Turkish culture: the gay, the sexual criminals of all sorts, the ethnic minority Armenians, Greeks and Jews, their slang and linguistic codes. His work is full of the burden of this revelation, simultaneously hiding and revealing, a revelation in the process of occurring.

50

In the poetry of The Second New, from the mid 1950’s to the mid 1970’s, Istanbul as a psychic landscape is sliced into four. The Bosporus divides the Asian from the European side and opens to the Istanbul harbor. Except for İlhan Berk, most of the poetry up to Ayhan, including Veli’s and Süreya’s, is focused on the Bosporus landscape. This is the Islamic, official side of Istanbul, a city of extreme beauty. Its eroticism, except for the short story writer Sait Faik whose casual, lackadaisical seeming style is saturated with an unpronounceable language, is heterosexual.

51

The second division occurs between the old city — the site of the Topaki Palace, the major mosques and the Hagia Sophia, that is to say, the site of the old Byzantium which the Ottomans conquered — and the new city The two parts are split by the Golden Horn, which is an extension of the Istanbul harbor. The Golden Horn creates a sky line of mosques on the old city side and is crossed by the Galata Bridge at the entrance to the harbor. The new city, built on a hill, is called Galata (or Pera). It is a district of crooked, winding streets where the Turkish minorities, Armenians, Greeks and Jews, reside; it also contains the red-light areas, divey bars, whore-houses, transvestite corners of Istanbul.

52

Ece Ayhan brings Galata as the place of the forbidden, politically invisible, feminine into Turkish poetry; he expands Istanbul as a poetic landscape. He does it first through puns between the straight and street meanings of words. For instance, Orthodoxies, title of one of his books, refers to Orthodox Christianity, and metaphorically to holiness, saintliness; but in slang the word means whoredom, homosexuality, pederasty, betrayal. His poetry is also permeated with people’s or place names, often suggesting a secret, double life: Hamparsum, the famous Armenian composer of Ottoman music; Bald Hassan, a theatrical stock character always appearing with a broom; Peruz, a famous transvestite singer; Al Kazar, at the time a theatre of adventure movies frequented by child molesters; Three Angels, a Christian chapel. Fetishistically, names are secret places in the body of Istanbul.

53

In The Second New Istanbul has a distinct shape, that of a city of one and a half million split into the dichotomy of open and secret, old and new, Moslem and Levantine, strait and gay. The movement articulates its poetic project of expanding consciousness by working through the city in depth: Süreya by connecting the erotic (the secret) with power, seductions occur on the water, by a wall, etc.; Ayhan by mentioning names, expressions belonging to the social and historical underbelly of the city. This pursuit of secrets is the metaphysical resonance driving the Second New poets.

54

The association of Istanbul with feminine sensuality and a site/sight of secrets has been there since Byzantine times. When Herman Melville visits “Constantinople” almost exactly one hundred years before The Second New, he sees, reacts to the city exactly the same way: “The fog only lifted from about the skirts of the city, which [was] built upon a promontory... It was a coy disclosure, a kind of coquetting, leaving room for the imagination & heightening the scene. Constantinople, like her Sultanas, was thus veiled in her ‘ashmak’”. (Journals, Herman Melville, The Northwestern-Newberry Edition, p.58). The bridge Melville crosses and re-crosses and writes about, the steep road where he feels lost in a crowd of people are more or less the same city, of the same size, Süreya, Ayhan and Turgut Uyar write about.

The 1990’s, the Poetry of Motion:

Back to Contents (top of page)

55

like a bridge, departing from myself

like a Turk, red, I am crying turkish red (from turkish red, Lale Müldür)

56

In broad outlines, the development of Turkish poetry in the 20th century has a dialectic shape; majors works get written almost simultaneously, by Hashim and Beyatli, Hikmet and Veli, Süreya and Ayhan, interspersed by relatively fallow stretches. The years between the middle of 1970’s to the late 1980’s is such a fallow period.

57

From the onset of The Second New, a crucial event undermining the movement started to occur; Istanbul began its exponential growth. The first shot of this process was a 20th century Haussmann project in the late 1950’s. The Menderes government tore down the historical district of Aksaray to build a multi-laned road to accommodate the upcoming flood of Anatolian population into the city. By the early 1980’s two bridges had been built over the Bosporus (one of the psychic dividers of Istanbul’s landscape) and many of the beautiful old konaks (villas) on it (areas Beyatli, Veli, Uyar write about) were destroyed. Istanbul had been transformed from a city of secrets, depth into a nexus of movement, a sprawling, global metropolis.

58

Here lies the poetic crisis of 1970’s and 1980’s. Poets struggling with the legacy of The Second New faced a city which corresponded less and less to it. How to find a poetic language reflecting the new shape of the city, making it once more part of a spiritual language?

59

The poetry of this transformed landscape explodes, once again, almost simultaneously in a series of poems and books published between 1991 and 1997: Lale Müldür’s “Waking to Constantinople” (“Konstantinopolis’e Uyanmak”) in A Book of Series (Seriler Kitabı), Sami Baydar’s lyric poems the first book of which is The Gentlemen of the World (Dünya Efendileri, 1987), Ahmet Güntan’s Romeo and Romeo (Romeo ve Romeo), küçük İskender’s souljam (cangüncem), Seyhan Erözçelik’s Rosestrikes and Coffee Grounds (Gül veTelve) and Enis Batur’s East-West Divan (Doğu-Batı Divanı).

60

These works share crucial similarities. First, they are all essentially poems of movement, rather than depth. In Romeo and Romeo two lovers move around each other in a abstract dance to reach an elusive center. The most striking aspect of souljam is the chaotic, expansive energy which spins fragments, seemingly at random, away from each other, though a cadence of yearning runs through and unifies them. The poem Coffee grounds is twenty-four Rorschach tests made of coffee grounds over which the eye spins meandering narratives of fortune and hope, cajoled by a listener. In the narratives in East-West Divan the teller and listener are fused in a continuous weaving motion. In Sami Baydar’s poems images, like water, keep changing without any definable logic, tracing the sinuous contour of something invisible; waves point to the space between them (“The Sea Bird”), a pitcher to the water inside (“Pitcher”), biographical fragments to the soul running through the fragments (“Jacket”).

61

In the poetry of the 1990’s Istanbul changes from a physical place into an idea, an elusive there, a basically mystical, dream space of pure motion. In no poem is this more clear than in Müldür’s “Waking to Constantinople.” In it the contemporary urban sprawl of Istanbul is re-imagined as a historical sprawl during which the city was continuously destroyed and re-built. In Mobius-like connections the poem weaves a synthesis between the Byzantine dream world and Ottoman rationality, time opening up as a continuum, and Istanbul dialectically being given a new name.

62

“Waking to Constantinople” achieves its conceptual links through long, sinuous lines which almost become prose. The teasing with the limits of a poetic line is a stylistic identifying mark of four of the poems mentioned above. Through it often depth turns into a poetry of motion. The long poetic line was created by İlhan Berk, the third poet associated with The Second New. His work makes the explosion of the 1990’s possible; in him one sees how movements of the mind and Istanbul as the city of motion join.

* *

63

THE GARDEN DETESTS CALENDESTINE OPERATIONS (İlhan Berk)

64

Though associated with The Second New. Berk’s poetry has little to do with depth, everything to do with motion. Born before Süreya and Ayhan and still alive — that is to say, writing more than sixty years — his work assimilates the poetic movements from Hikmet and Veli on. The great pleasure of Berk’s poetry is to follow his agile mind weaving in and out of historical time periods, following the contours of crooked streets in Galata, naming names, or stopping at a now defunct whore house listening to the voices of women there. In “Garlic,” ostensibly a prose piece, time as a layered entity with past and present disappears and becomes a unified place of the spirit, of mind play.

65

In Berk, Süreya’s sense of unexpected connections and Ayhan’s awareness that Istanbul is a mongrel accumulation floating on a sea of history are unified into a flat tapestry of pure motion, an irreligious but still spiritual space where splits associated with time are abandoned. Berk’s poetry reveals no secrets but lights everything it touches with its inflections.

66

From the 1950’s on, everything Berk writes is associated with his “long poetic line.” To understand what that line is, one can go to a Haşım poem, the first poet in the anthology: “In a grieving perfection’s insomnia...”Why is perfection associated with insomnia? Insomnia is the most intense state of wakefulness (consciousness) because it is nearest sleep. This is a poetics of limits, a motion of the mind towards zero, the unreachable, the forbidden.

67

Berk’s long poetic line approaches the limit of prose, growing in intensity doing so. A lot of Berk’s best poems look like prose; they are continuous strips of poetic line moving towards and away from a limit. Here lies the essential paradox of Berk and Turkish poetry. He seems to be the most pagan, least religious of poets, as Turkish poetry rarely is about religion. But an irreducible spiritual essence runs through both of them, as it does in Veli or Hashim or Hikmet or Süreya or İskender or Güntan.... It is buried in the agglutinative cadences of Turkish, a language of affections inflected by proximity to a movable, elusive verb — a dance towards and away from limits. The sensual, metaphysical and historical are unified in this movement — the Eda — a continuum of earth, water and human habitation:

68

...

I SEE THE HOUSE AFTER I LEAVE THE GARDEN BEHIND.

To compare the garden and the house: the garden is wide open in the face of the close-mouthed, conservative quality the house characterizes (permeated with that despotism which wounded it long ago).

69

THE GARDEN DETESTS CALENDESTINE OPERATIONS.

Full of sound and voices.

Its face overflowing into the street.

Offering a female reading.

To compare them, it is sexual (what is not?)

70

THE HOUSE IS MORE AS IF TO DIE IN THAN TO LIVE IN.

Oh garden, the muddy singer of the street.

“Dirty Child.”

Hello gardens, here I am! (from Houses, İlhan Berk, translated by Önder Otçu)

* *

71

Unless otherwise specified, the translations in this anthology are my own. They run the gamut from being absolutely literal to a few where I took liberties. But in all I tried to be absolutely faithful to what I believe their essences are. My attempt was always to translate that essence without diluting it. I followed the same principle choosing the translations of others.

72

Any failures in this intention belong to me.

73

I have tried to date the poems whenever possible. This is important because the growth of Turkish poetry has an inner logic. Also, a few major poets before the 1960’s, particularly Beyatli and Hikmet, did not have their works published in book form until decades later than when they wrote them. One of the wonders of Turkish poetry is that the influence of these poets often does not start with their publications, but with their writing. The succeeding poets seem to integrate their achievements through osmosis, in response to a wider linguistic and cultural process to which they belong.

74

Whenever there was an option, I chose the earliest available date, either the writing date given by the poet or the publication date in a magazine or in the book in which the poem appears.

from “Turkey’s Mysterious Motions and Turkish Poetry,” “Eda and the Poetry of Motion [47]

Back to Contents (top of page)

75

[....] From the 1920’s to 1997, Istanbul altered from a city of well under a million to a metropolis of twelve million. Numerically, the explosion started in the late 1950’s with the beginning of the influx of the Anatolian population for work into the city. But in the early 1990’s Istanbul underwent a subtle conceptual transformation, in addition to its numerical one. With the fall of the Soviet Union, it became an economic and spiritual focal point as people converged from former satellite countries in the West and Turkish republics in the East, in search of goods and ideas formerly unavailable or suppressed in their countries. At this point, Istanbul became transformed from a national city of twelve million to a global metropolis, a crossing point of conflicting dreams.

76

Eda reflects this tectonic, strategic change. In the 1990’s, Turkish poetry underwent an intense creative period in a sequence of startling poems. The previous peak period, which ran roughly from the early 1950’s to 1970’s [The Second New, see “The Idea of a Book, Eda: An Anthology, section “Poetry and History], created a poetry of depth, splitting Istanbul and language into visible and secret places. In the new poetry the language flattens. The stylistic essence of the best poems of the 1990’s is motion. Often written in long sinuous lines, in them the thought, the eye, the image never stay in one place, constantly shifting conceptual, ideological, or identity lines. The music of this motion across borders — the Eda echoes Istanbul as the global city.

77

In each poem, two seemingly irreconcilable concepts (or desires) are superimposed on each other, creating a flat, unified field. The poems reflect the impulse towards synthesis at the heart of contemporary Turkish poetry.

...

from “Ideas Towards a Theory of Translation in Eda [48]

Back to Contents (top of page)

I

78

No gendered pronouns, no stable word order, Turkish is a tongue of radical melancholia. (“The Idea of a Book,” Eda: an Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry)

79

The above statement, which seems to be about the Turkish language, in truth is also an analysis of English. The statement asserts a tension, a dialectic between the two languages, removing the grammars of both from their states of naturalness. Substantiating them both, it turns them both into distinct systems of contemplation — what is there, and what is not here..

80

For instance, the natural thing for a Turkish translator to do is to use the appropriate gender pronoun in given passages. In Eda, I follow the reverse system. Unless the gender reference is absolutely specific, I shift the pronoun. This method — which results in a “translated text” which is more distant, more unsettling to the host reader — has two reasons. A submerged theme of coded homosexuality exists in the 20th Turkish poetry, a theme that gradually is liberated and comes to the surface. The Eda anthology is interested in this process of liberation.

81

Second, because the very concept of distinctions, between animate and inanimate, object and human, male and female, love and sex, human or divine does not exist in Sufism, which is the metaphysics at the heart of this language and poetry.

82

Consequently, the strategy of distance, of subtle disorientation becomes a portal to enter, or at least get a hint of, a completely different cultural matrix. The translation involves itself not only with individual poems, but also the society, the city, the culture in which the poem lives, from which it derives. The radical melancholia is hooked to a specific mode of consciousness, as it works itself through a specific language.

II

83

In Eda a state of being is transformed into a movement, dance of language. It does so by creating a narrative in which there are three characters. The first is the city of Istanbul, the body, the space in which the movement of the spirit occurs. The second is Turkish itself, a totally agglutinative language, with an absolutely flexible, permutable word order, which enables the language to record very subtle nuances of feeling, to record the process of perception as it emerges. The third is Sufism, originating from Central Asian Shamanism, which intuits a deep unity in multiplicity, in chaos. This impulse to unity balances the vertiginous impulse of the Turkish language and society towards chaos. It enables a state of extreme differentiation, in culture and poetry, to thrive as a living organism.

84

In Eda both sides of the translation pole see themselves in a new way, emerging from out of their systems. Turkish becomes aware of Eda as an organizing principle. In point of fact, this anthology, which includes many essays, basically written as a tool of understanding for Western audiences, has had a surprising and crucial function of self-definition for Turkish poets and critics. For once, they were able to see their achievements in their own terms, without being co-opted by Western terminology or thought systems, such as surrealism or symbolism, etc.

85

For the Western reader the situation is more complex, because Eda avoids familiar templates, points of reference to make the material familiar. The relationship is tangential, the text existing as a meta-language, which basically what translation is. It presents to the host language reader a field, a dream of possible alternatives, which the host language can or may not take.

86

In that way, in a translation both languages move to a third place where language sees or may have the possibility of seeing itself in a new perspective, in that way transforming itself.

Translation and Style [49]

Back to Contents (top of page)

87

Understanding translation is embedded in the concept of faithfulness. What is a faithful translation? The traditional answer is Platonic, best represented in our day by the critic George Steiner, especially in his introduction to The Penguin Book of Modern Verse Translation (1966). According to this view, the original poem exists in an ideal, static state, and the translator attempts to transmigrate this ideal totality into the second language. Since two languages never “mesh perfectly,” a translation can never be completely successful; something is lost. Steiner quotes Du Bellay to that effect: “That it is untranslatable is one of the definitions of poetry. What remains after the attempt, intact and uncommunicated, is the original poem.”

88

In this traditional approach, completely successful translations are rare, discontinuous, mystical happenings, “a medium of communicative energy which somehow reconciles both languages in a tongue deeper, more comprehensive than either.”

89

The problem with the traditional, Steiner approach is that it is a-historical, empirically incorrect. Major achievements and transformations in a language are often associated with translations. To cite only English cases, Chaucer’s “Troilus and Criseyde,” Sidney’s translations from Petrarch, the King James version of the Bible, Ezra Pound’s “The Seafarer” from the Anglo-Saxon and “Exile’s Letter” from Li Po, each of which played a key role in reorienting the English language.

90

These translations are based on a different concept of faithfulness. They fragment the original totality, starting with a conception of “lack.” The translations senses a quality in the original language, reflected in the original poem, which the second language lacks. The translator is faithful to this conception and tries to recreate it in the second language. A translation in this sense starts with criticism and ends by pointing, not to the first, but to the second language. It explores the second language and, if successful, changes it by assimilating this lack. I define this kind of translation a transparent text.

91

The ideal of transparent translation is not to be perfect in terms of a Platonic concept of wholeness but to create shifts in the second language. In fact, subtle distortions due to fragmentation and misreadings caused by the central vision of lack are integral parts of it, often pointing to some of its most successful moments.

92

One quality often regarded as a virtue in the traditional approach is a red flag of failure in the transparent translation: making the language of the translation so natural as though it were a poem written in that language, not a translation at all.

93

This is the sure sign of a bad translation, not worth reading. A successful translation must sound somewhat alien, strange, not because it is awkward or unaware of the resources or nature of the second language, but because it expresses something new in it. The best ones remain strange even after poems deriving from them make them more familiar. They affect the course of a language without being entirely part of it. A translation completely assimilated into the conventions, norms, of the second language, solely acceptable in its terms, is a failure.

94

This strangeness endures because in a transparent translation, style often precedes meaning, which, in the form of theme or feeling, is transformed when attached to stylistic expansion. A transparent translation always has an independent stylistic identity. This is why Walter Benjamin says in his essay, “The Task of the Translator,” that meaning is attached to a translation “loosely.” In original poems, style appears contingent on meaning, more integrated with it.

95

In its suggestiveness describing the relationship between two languages during translation, Benjamin’s essay is a powerful text. At its center, it asserts that the foreignness of a work that makes it translatable: “The higher the level of the work, the more does it remain translatable even if its meaning is touched upon fleetingly.” This thought is one step from the concepts of lack and fragmentation, which define transparent translation. But Benjamin’s ideas are, linguistically, intricately linked to, dominated by Hegelian idealism, which contradicts and finally thwarts their developments. He sees a perfect translation to reside in an ideal, pre-Babel state a “hitherto inaccessible realm of reconciliation and fulfillment of languages.” This concept is regressive in two ways. First, it retains the ghost of a perfect match, which his essay also negates. Steiner’s introduction is a restatement of the idealistic side of Benjamin’s text. Second, it leaves Benjamin completely silent on the relationship of the translation to the second language.

96

The present essay tries to demythologize Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator” from Hegelian idealism to the American practicality, by fragmenting and exploiting contradictions inherent in it. The focus here is the relationship of a translation, not to the first, but to the second language — different ways in which that language is altered and expanded.

97

“The Seafarer” is, along with “Exile’s Letter,” perhaps the major transparent translation in the twentieth century in English. Pound’s focus translating this poem is sound, the harsh sound he hears in Anglo-Saxon. “The Seafarer” is part of Pound’s “heave to overthrow the iambic.” The result is not a natural English poem recreating the syntax and the meter of the original; its purpose is rather to force a shift from vowels to consonants as the organizing principle of a poem in English. By making the substance of the language more palpable, through inversions and abundance of consonants, it opens the door to making language itself a subject matter, the equivalent of Picasso’s and Braque’s revolutions in sculpture, “Bosque taketh blossom, cometh beauty of berries.” There is a direct link between “The Seafarer,” Louis Zukofsky, and the language poets.

98

In a successful transparent translation, much more than the surface gets transposed: “He hath not heart for harping, nor in ring-having / Nor winsomeness to wife, nor world’s delight...” “Winsomeness” is a medieval, not an Anglo-Saxon concept. In this subtle distortion, at this moment, “The Seafarer” is a translation from a Provençal poem.

99

The theme of exile itself is another dimension that “The Seafarer” transposes from Anglo-Saxon into English. Not only does it appear in the figure of Ulysses at the beginning of The Cantos, but, as Charles Bernstein point out, for Gertrude Stein, Louis Zukofsky, and Charles Reznikoff, English was not the language they grew up in. In fact, as writers, they tended to treat it as a foreign language. Their works can be seen as translations, transparent texts, from their alien language, English, into their private idioms, a reason for their strong stylistic identity. Their relationship to English are those of linguistic exiles. “The Seafarer” creates a shift in English which is not in the original. It points out that a plastic involvement with language entails a distancing between the writer and the language — and consequently between the writer and the audience. The Anglo-Saxon original was a poem accompanied by music, implicitly for an audience. “The Seafarer” is a poem to be read by an individual. Finally it is the most radical, significant bent Ezra Pound creates in the original.

100

I, Orhan Veli (Hanging Loose Press, 1988), consisting of my translations of poems by the Turkish poet Orhan Veli (1914–1950), is another example of a transparent translation. Its purpose is to alter intimacy, between reader and poem, by redefining colloquial speech. On the one hand, it possesses, I hope, the sounds, the smells, the music of a strange city, Istanbul; on the other hand, the voice feels very much as if it belonged to New York, like a New York voice.

101

This contradiction is at the heart of the shift I, Orhan Veli tries to create in contemporary colloquial speech. In American speech, colloquialism is often associated with natural speech. informality and streetwise humor. Though I, Orhan Veli reflects that, it also has a contemplative, melancholy, lyrical dimension. It is this dimension which is new and which sounds Turkish in the poems. It makes the colloquial speech, as though the reader were walking side by side with the poet, overhearing his conversation.

102

This intimacy is reinforced by the way these translations alter the concept of poetic closure. Generally, Orhan Veli’s poems and these translations end where the subject matter ends, not where the poetic tradition expects them to end. The result is a seamless clarity, language pushing away from itself, losing body, as though these were not poems but overheard pieces of conversation. This helps replace the figure of the exile, the solitary prophet, by a friend.

103

I, Orhan Veli’s colloquialism is not really daily speech. It is a very terse, precise abstraction from it, its stylistic, plastic identity as a translation. The purpose of I, Orhan Veli is to create a clear hard-edged sharpness, also relaxed and intimate. It is an offshoot of the clarification, at moments the spiritualization, of language that Pound started in Cathay, particularly with Li Po’s “Exile’s Letter,” and which poets on and off — T.S. Eliot in the garden sequence of Burnt Norton, a good portion of Charles Reznikoff, John Yau’s “A Suite of Imitations After Reading Translations of Poems by Li He and Li Shang-yin” — try to continue.

Back to Contents (top of page)

The Double Vision of Translation *

* This essay “The Double Vision of Translation” was written

by Murat Nemet-Nejat explicitly for this Jacket feature.

104

No language can fulfill its intention alone but must join the intentions of other languages supplementing each other in the realm of ‘pure language.’ (Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”)

105

“Translation does not translate meaning but a glimpse of the lack of it–the feeble insufficiency of the host language.”(“Translation: Contemplating Against the Grain,” http://www.cipherjournal.com/html/nemet-nejat_spicer.html)

106

Translation has two perspectives, one from the angle of the original language; this is important particularly if the source is minor in relation to the target language. This minority -a real lack of adulthood from the point of view of the target language- can be contemporaneous, that is to say, political, for instance, in the relationship of a poem in Croatian to be translated into English. Or, it can be historical, due to the apparent waning of a language through time by a lack of specific usage, like Latin, Greek or Aramaic. In both cases, from the point of view of the source language, translation involves a process of re-valuation, self criticism, a bringing up to consciousness what was unconscious, implicit. In other words, translation is an act of reassertion, an analysis by language of its own self leading to consciousness. (Of course, unless the main purpose of the translation is ingratiation, selecting aspects in the original most like the target language or imagining them into being as such in the act of translation. But this is not the kind of translation I am interested in.)

107

The ideal translator from the point of view of the original language is a native speaker, a poet with a strong critical impulse; translation always starts with a critical impulse. Translation is that literary genre where language is treated not as a medium of communication, but as a structure of meaning production. The translator is an artisan of meaning production, more someone telling how a clock works than what time it tells.

108

Of course, from the angle of the original language, the translation tells the translator’s own time, but culturally. It tells its sacredness, its autonomy. The translator becomes the technician of that sacredness, the sacredness buried in words. It has little to do with personal identity.

109

Going back to the original idea, from the point of view of the original language, what the translation elicits to the surface is that language’s innate sacredness. From the angle of the host language, the receiver first experiences this sacredness as style.

110

The sacredness of The Bible in English is in its King James cadences (deriving from Babylonian rhythms) and its odd turns of phrases. The sacredness of Anglo-Saxon is in its harsh, consonant filled, alliterative sounds. The sacredness of Turkish is its sinuous, feminine, continuously moving lines. The sacredness of Sappho is the extreme fragmentations of the extant poems. The sacredness of The Talmud is the extreme plethora of its arguments, the almost phantasmagoric documentation more or less democratically of every nook and crevice of its culture, in a kind of ur- Wikipedia. .

111

Style created by translation–the telltale sign of the sacred in the original- hangs tangentially on the target language, as a specific definable quality, without quite becoming part of its tradition. It remains as a template, a distinct and somewhat distant meta language that poets in the target language can allude or aspire to, can pick from without quite appropriating it. As a result the style created by a translation does not change, but remains as an ideal, a linguistic sign of a sacredness of the other, which in specific incarnations the target language can only embody fleetingly, in fragments.

112

In Eda: An Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry, I tried to bring to English a specific style of the sacred, Eda, a conceptual essence very concrete and sensual in its different manifestations, yet always to some extent elusive, not completely appropriated or explained away.

113

Here, I think, one arrives at a surprising, yet complementary conclusion. In the original language, translation moves towards a state of self-consciousness, detaching the culture–linguistically its sacred, ideal core- from, in Walter Benjamin’s words, its specific “modes of intention.” On the other hand, in the target language, the translation remains detached, not completely appropriated; remaining elusive, therefore, it does not merge into the modes of intention of the second language. Remaining an ideal, a template, pointing to what the target language lacks–its partly alien vision- it makes the second language stretch, what in another context I call “grow a new limb,” pulling it also out of the limits of its own modes, its closed system.

114

This way, both languages move, not from A to B, but to a third ideal place, stripping off their closed systems, where all languages exist in a single continuum , moving in multiple vectors, a meta-language which exists parallel to the specific modes of the two languages. In this meta-language all translations unite and interact. Within the context of this anthology, as an imperial language, with its vague specifity, American English acts as a clearing house, from which the “minority” of other languages can receive and add to. In this way, in its meta-language form, the imperial, image making power of American English is subverted, de-boned, becoming a tool, a medium of outsider communications.

2007

Herman Melville, Charles Olson and Moby Dick as a Sufi Poem, a Footnote [50]

Back to Contents (top of page)

115

On December 12, 1856, from his boat seeing Constantinople (Istanbul) for the first time, Herman Melville sensed instinctively the erotic dimension, the mixture of the secret and the revealed, that the city possesses: “The fog lifted from about the skirts of the city, which being built upon a promontory.... It was a coy disclosure, a kind of coquetting, leaving room for the imagination & heightening the scene. Constantinople, like her Sultanas, was thus veiled in her ‘ashmack.’” [51]

116

The journal Herman Melville wrote during his twelve-day stay in Constantinople [52], obsessively tracing and retracing different parts of the city, particularly its Galata Bridge, [53] trying to make a sense out of what he sees, with their sexual, possibly homosexual undertones, constitutes a Second New [54] poem. In Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson notices a connection between Melville’s experiences of Istanbul and of the Pacific Ocean: “When he leans over the First Bridge [The Galata Bridge] [55] his body is alive as it has not been since he swung with Jack Chase in maintops above the Pacific.” [56] Melville’s journal of his stay has no overt references to the ocean or Moby Dick ; the matter-of-factness of the writing, resisting symbolism, seeing the city in its own terms, full of place names, devoid of Western sentimentalities, is what makes it remarkable. Nevertheless, the allure of Constantinople as a “sultana,” and the “sultanisms” of his obsessed, dictatorial Ahab [57], who drew charts of deeper, more cosmic oceanic currents, undreamt of by his more Western oriented Captain Starbuck, to meet his white whale, rejoin in the Eda of these diaries. The Pacific and the Istanbul harbor connect in a continuous, meta-Western current. In my view, Melville responds instinctively to the mystical dimension of Istanbul because he sees it as an ambiguous space, of beauty and death and stench, cypresses inside graveyards, revelation and secrets, where lust for power and its consequent loss are joint with sexual lust. His Ahab inhabits the same psychic space, a suicidal, elusive revenge, as Cemal Süreya’s seducer persona [58]. Pip and the boys he meets in Istanbul are the same boys as in Ece Ayhan’s poems. As Pip softens the “dictatorship” of Ahab’s “innermost center, “ the boys under the Galata Bridge touch Melville (isn’t Melville’s Holy Land pilgrimage a response by his family to his going mad after the writing of Moby Dick?). Ahab too “had a wife and a child” [59] before he went mad. Olson says Melville’s response to Istanbul shows his emerging “spontaneity” [60] to women; I am not so sure. As Pip in Moby Dick, the little children under the Galata Bridge are the redeeming heart of the Journals, not the “disappointment” [61] of Jerusalem or the interminable poem he wrote during that time.

117

Melville responds to Istanbul with Ahab’s “globular brain,” as if he spoke Turkish, in broad sweeps. Nowhere is this more clear than in a startling passage in the Journals where in a mosque he senses Central Asian connections: “Went to Mosque of Sultan Sulyman. The third in point of size & splendor. — — The Mosque is a sort of marble marquee of which the minarets (four or six) are the stakes. In fact when inside it struck me that the idea of this kind of edifice was borrowed from the tent.” [62] The madness of Ahab and Melville — as power, ego, self pursuing their loss in destructive compassion — is Sufi, ecstatic. Moby Dick and Journals are the great Sufi works of 19th century.

from Souljam: küçük İskender’s Subjectivity [63]

Back to Contents (top of page)

The Motions of Infinite Love:

118

Souljam is a big bang from the center of the soul, soul fragments — “pseudo-poems... vistas, unstudied formulations, experimental notes and delusions,” as küçük İskender’calls them in his introduction — pulling away from each other, while they yearn for a faetal or necrophilic unity. Existence, in souljam, is a series of explosions from and towards voids:

119

man finally dies because at his birth

the umbilical cord is cut (souljam, #646)

120

Violence is the pervasive catalyst in this process, in love, structure and language. The lover’s body in fragments through brutality, its missing emptiness elicits a yearning for union. The cadences of this spiritual yearning — an Eda unto death, of fragments infused with intimations of completeness — constitute the melody of the poem:

121

wounded electricity complements the body (souljam, #1)

122

is there any

lover of whose hands hands only statues are made,

oh, thine incorporeal hands! (souljam, #55)

Back to Contents (top of page)

123

Sufism necessitates the break down of the ego for the soul to enter its ascent towards God. In küçük İskender’s Sufism, the break down is in the lover’s physical body, the orgasmic point of his up-your-face sexuality. The ego does not break; to the contrary, remaining intact, constitutes the subjectivity within which the break down occurs. What the speaker is yearning, “jamming” for in souljam is the faetal/fatal limits of his explosive subjectivity, the infinite contours of his consciousness. İskender’s consciousness is God in his Sufism:

124

in a utopia where suicide is unknown

i’d like to settle as the god of suicide (cangüncem, #646)

* * *

125

The rough man entered the lover’s garden

It is woods now, my beautiful one, it is woods,

Gathering roses, he has broken their stems

They are dry now, my beautiful one, they are dry (Pir Sultan Abdal, a 16th century Turkish Sufi poet)

126

Violence (in spirituality and love) is at the heart of the Sufi sensibility, part of its Shamanistic, intuitive synthesis. İskender exploits, radicalizes the pagan essence of Sufism, its subversive ambiguity: the intimate link between God and self-destruction (sacrifice), sex and violence, love and death, religious fervor and political rebellion.

127

In Islamic Sufism violence is sublimated as a cosmic principle, partly, through the dialectics of arcs of ascent and descent. God’s unity breaks, dissipates into phenomenal multiplicity, while the broken down consciousness/yearning soul needs, through weeping, wine, sacrifice, etc., to re-enter a climb back to unity, to God. This psychic transformation (or simultaneity) between descent and ascent — a jump, a mystical “sleight of hand” — is the focus of a lot of Sufi poetry, from Rumi to Hafiz to a few young Turkish poets writing in the last decade of 20th century.

128

This moment of transformation is essentially subjective, of the mind’s eye. İskender radicalizes this subjectivity by casting out the validity/reality of the outside world altogether, implying that, in its most subversive extension, in Sufism, man’s mind is his God. Paradoxically, in this mysticism of completely of the mind, bound only by the psychic curvatures of birth and death (a kind of Einsteinian space) , he creates a text which is central, open-ended, inherently translatable.

Back to Contents (top of page)

129

küçük İskender’s poem is inherently translatable because of its intensely subjective universe. To understand this contradiction, one must go to its origin.

130

Souljam is a translation of İskender’s cangüncem (1996), itself a translation of the journal he kept, in twenty note-books, from February 19, 1984 to December 26, 1993. The poem reverses the order of the note-books, the lowest numbered fragments in cangüncem deriving from the chronologically latest note-book (#20), etc. Though basic themes and images remain the same, the chronological reversal utterly alters cangüncem from its time-bound, “journal” original. İskender describes the reason for the reversal in the following way:

131

an attempt... to suppress the chronological confusion, to push it to the very beginning, to a faetal sensibility.

132

Cangüncem records a faetal/fatal movement of the soul within the curvatures of total subjectivity, while the journal records ideas, images within the flow of time. This soulful movement contra time is the new thing canguncem adds while “translating,” crossing the linguistic void from the note-books to the poem.

Back to Contents (top of page)

Ahmet Güntan’s Romeo and Romeo: The Melody of Sufi Union

— first published in Eda: An Anthology.

133

Ahmet Güntan’s Romeo and Romeo is a love poem between two men — the title is the only clue to that — in which the lovers attempt to enter each others’ sleep to reach a mystical union. The five sections of the poem follow the steps in the sleep process: “The Hour of Sleep,” “Lullaby,” “Sleep,” “Dream,” “The Hour to Wake Up.”

134

Obstacles are hinted at during this pursuit of absolute union. The sleep and wake-up times of the two appear out of sync with each other, one waking up exactly when the other is going to sleep; there is also the hint a third person involved, a “he” or “she” or “it” (no gender distinction or distinction between animate and inanimate exists in Turkish). In the melody/argument of the poem, “I” argues that the logical impossibility of being at two places at the same time can be transcended in the loving act of penetrating another’s sleep because in this act one turns into the other person. Looking for the other, one finds oneself: “I’m with myself, alone, for myself,/ walking around, me, taking you out,/ who, u-turning, takes within you, me.”(“Dream”)

135

Entering another’s sleep is both an erotic and philosophical endeavor, related to the Sufi concept of “arc of ascent,” the process (also a curve, a melody) by which the distances among the elements fuse themselves into One Divine Light. This erotic yearning is also a movement of the mind, towards justice, the purified simplicity of mathematics. In the final two lines of the poem, Romeo and Justice become one: “Justice Romeo!//Justice, my Romeo!” (“The Hour to Wake Up”)

136

Quite small in vocabulary, Turkish has a “radial” tendency, different meanings and grammatical functions converging, collapsing into the same words, sounds. The poem exploits this tendency, turning itself into the sound of Sufi union, the melody of the “arc of ascent.” Its intentionally minimalist vocabulary creates infinite variations, few words echoing and circling around each other, pulling towards a center: “Sleep with me, you,/in sleep you depart, from me,/in sleep I forget, I, I/depart from you.” (“Sleep”)

137

Economy is at the heart of Turkish literature, of that aspect which has Central Asian, pre-Islamic connections. Sufism has similar roots. Romeo and Romeo echoes the rhythms of the 13th century Sufi folk poet, Yunus Emre. One might call Romeo and Romeo a gay spiritual written at the start of the third millennium.

138

This spirituality is anti-western, anti-modern — if one takes these terms to mean what has happened after the Renaissance in the West. It builds a bridge between ideas implicit in Arnold Schønberg and John Cage and traditions outside the West — specifically the Islam, which was the ideological antagonist of the West until the 16th-17th centuries. With roots in Plato, believing in the spirituality of colors and design, the Moorish and Sufi strains of Islam absolutely believe in the unity between the mind and the senses. Cartesian duality and its variations are inconceivable. In fact, embodiments of “the arc of ascent” are exercises of denial of this duality. It is this historical, intellectual challenge which makes Ahmet Güntan’s poem and the works of a few other Turkish poets around him (Lale Müldür, Sami Baydar, Seyhan Erözçelik, küçük İskender, Enis Batur) so exciting and of such great value.

The Materialist Poem:

“Godless Sufism,” as the Structure of Matter in the Turkish Poetry of Our Day

by Murat Efe Balikçioglu

139

“The Manifesto for a Materialist Poetry,” which Cam Kurtuluş and I published in May of 2004, possesses, contrary to what the title suggests, not simply an anti-religiosity, but a mysticism, in addition to a materialism permeated in places with a nihilistic attitude. This is a structure created by a collision of the aesthetic with the metaphysical. While the aesthetic symbolizes the anxiety for style and the daring, interrogational attitude capable of denying the existence of God — the avant-garde — the metaphysical shelters a mystical attitude, believing in God. The Materialist Poem is a latent metaphysical composition embedded within an aesthetic crust. Consequently, as Murat Nemet-Nejat also delineates in his concept of “Godless Sufism,” the Materialist Poem is the godless but Sufi Eda of the poetry of the generation of the youth of our time. It is possible to see this in the poetry which, by building connections with objects, I wrote directly on them. Inspired by Jean Debuffet’s sculpture Four Trees exhibited in the Financial District of New York City, these poems, rather materialist poems, inscribed on street lamps, walls, pissoires, tables, couches, served up benefiting from experiments with objects, reveal a mental dimension. In other words, the first instant it begins to interact with an object, the mind, in the duration of a second, thinking of everything, creating a connection with it, writes its poem on the object. Improvised, the poetry of matter transfers in that instant whatever it can distil from the millions of information in the mind to the matter. In that way, it concrete-izes, material-izes the thought of that instant.* This may be considered as the ultimate connection the human being enters with matter; but it does not mean that writing on matter leaves metaphysical dimensions behind, without transferring them onto matter. In Sufism, matter is precious because it stands, it “thinks,” silently it traces everything. Consequently, while in “materialist” philosophy matter can be considered distant from metaphysics, in Sufism it is mysticism itself; matter is its secret identity.

— 2007 [Jacket is the first publication of this essay.]

[43] Eda: An Anthology—

[44] In his Journals, Herman Melville sees in Ottoman mosques the simple design of a tent, the habitation form in Central Asian steppes from which the Ottoman Turks came.

[45] The city of disco bars whose basement forms a Byzantine palace: This is literally true in the Laleli district in Istanbul where the rooms of a Byzantine palace, with its columns intact, are used as basement storage places by businesses above.

[46] Gilles Deleuze, essays . critical and clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1997), p. 61.

[47] Bayreuth: Daily Star, November 20, 2004; U of Texas at Dallas: Translation Review, No. 68, 2004.

[48] The entirety of the essay, which was a talk given at The Stevens Institute in New Jersey during a Romanian poetry conference in 2007, can be read at the International Exchange for Poetic Invention blog (http://poeticinvention.blogspot.com/search/label/turkish%20poetry). It was published in Talisman magazine: Jersey City: Talisman, no. 35 Fall 2007, pp. 117–121.

[49] Murat Nemet-Nejat. “Translation and Style, Jersey City: Talisman, no. 6, Spring 1991, pp. 98-100.

[50] This footnote is from the essay, “A Godless Sufism: Ideas on the Twentieth Century Turkish Poetry,” which focuses on 1955–1970 The Second New movement in Turkish poetry (Jersey City: Talisman, . no 14 Fall issue, 1995; Eda: An Anthology — , 2004).

[51] Journals: The Writings Of Herman Melville, vol. 15, edited by Howard C. Horsford with Lynn Horth, Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1989, p. 58)

[52] Journals, pp. 58-68

[53] The Galata Bridge connects across The Golden Horn the relatively new Galata section of Istanbul, where the ethnic minorities lived in the 19th century and the red light district was located, to the older section, where the old Byzantium and the Ottoman Topkapi Palace were located. This bridge, originally designed by Leonardo da Vinci but built in the 19th century, is different from the two 20th century bridges across The Bosporus which connect the European side of the city to its Asian side.

[54] See the essay “The Idea of a Book,” section “History and Poetry.”

[55] The poet Orhan Veli has a poem, “The Galata Bridge, ” exactly from the same location as where Melville is leaning over and describing what he sees.

[56] Charles Olson, Call Me Ishmael: A Study of Melville, San Francisco: City Light Books, 1947, p.95.

[57] "The Specksynder," Moby Dick.

[58] See “The Idea of a Book,” section “History and Poetry.”

[59] Call Me Ishmael, p. 61.

[60] Call Me Ishmael, p. 95.

[61] Journals, p. 91.

[62] Journals, p. 60.

[63] Eda: An Anthology.

Murat Nemet-Nejat

Murat Nemet-Nejat graduated from Robert College in Turkey and studied

literature at Amherst College and Columbia University. Married, with two

children, he has lived in the United States since 1959.

Murat Nemet-Nejat’s work includes: “”I Did My Best Work During a

Writer’s Block, First Intensity, 2008; Possibilities of Istanbul (a visual and textual approach), Nina Reisinger, Austria, 2006; “Rooster Street ,” Both Both, 2006; “Eleven Septembers Later: Readings of Benjamin Hollander’s Vigilance,” Beyond Baroque Books, 2005; Eda: An Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry, Talisman House, 2004; Frédéric Brenner. Diaspora: homelands in exile, voices

(essays), HarperCollins Publishers, 2003; The Peripheral Space of

Photography, Green Integer Press, 2003; “Steps,”Mirage, 2003; “A 13th Century Dream,” Cipher Journal, 2002,

http://www.cipherjournal.com/html/13th_century_dream.html;

Aishe Series and Other Harbor Poems, 2001; Io’s Song, 1998;

Ece Ayhan. A Blind Cat Black and Orthodoxies. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon

Press, 1997; “Questions of Accent,” The Exquisite Corpse,

1993, also in Thus Spake the Corpse: An Exquisite Corpse Reader (1988–98), Volume I, Poetry and Essays (Santa Rosa: Black Sparrow Press, 1999); see

http://www.cs.rpi.edu/~sibel/poetry/poems/murat_nemet_nejat/essay/questions_of_accent.html;

Turkish Voices (see this website: http://www.cs.rpi.edu/~sibel/poetry/books/turkish_voices/), The World, 1992; Veli, Orhan. I,

Orhan Veli. New York: Hanging Loose Press, 1989; The Bridge. London:

Martin Brian & O’Keeffe, Ltd., 1977. “Automic Piles” (a science-fictin essay), 1983 (see http://ziyalan.com/marmara/murat_nemet-nejat2.html.

For the last three years Murat Nemet-Nejat has been working on a long poem The Structure of Escape. He is also currently translating the Turkish poet Seyhan Erozçelik’s book Rosestrikes and Coffee Grinds (Gül ve Telve) in its entirety, which will be published by Talisman House in 2008.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/eda-essays.shtml