Alexander Dickow

reviews

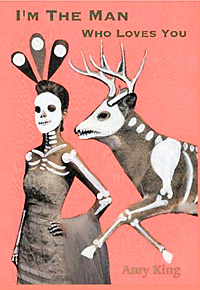

I’m The Man Who Loves You

by Amy King

87pp. Buffalo, NY: BlazeVOX Books, 2007 (www.blazevox.org: print on demand, order online). Paperback US$16.00. ISBN 1934289337.

This review is about 5 printed pages long. It is copyright © Alexander Dickow and Jacket magazine 2007.

^

Although already familiar with one of Amy King’s earlier BlazeVOX chapbooks, it was reading King’s poem ‘I’m The Man Who Loves You’ on her blog that convinced me her work deserved greater attention, and I awaited the book’s release with some impatience. Among the most outstanding in the collection, the title-poem performs a perfect arc:

^

The history of the scarf is in knots and I don’t know

if that’s a compliment or a fact-finding gesture,

[.....]

[...] the closest I’ve ever come to understanding

a human being in the measure of a scarf that shares its warmth

to the degree of tight to loosely tied around her

open neck and also as a mask for her nose against eternal elements.

^

Evoking Hopkins’ ‘It Was a Hard Thing to Undo This Knot,’ the scarf’s entangled history condenses and encloses the poem’s dizzying convolution into a single, circular emblem.

Amy King

^

One might apply this emblem to Amy King’s work as a whole, as Annie Finch has done in her comments on King’s book, alluding to the latter’s ‘vital and ineluctable complexity’ and to the use of ‘near-Elizabethan conceit’ (back cover). In the same poem quoted above, King displays her taste for paradox, conceptual knots and conundrums:

^

[...] I named my dog for the future except

I couldn’t remember what we’d all been calling her by then [...].

^

My own preference for the baroque attracts me to these occasionally excessive verbal ripples and folds (is excess a negative quality?). Only Lautréamont’s contorted syllogisms can compare: they are never opaque, never senseless, but disfigured just enough to provoke a double-take:

^

What comes now? None of us died

the very moment that so many of us are still alive. (‘Vie quotidienne’)

^

Referring to the ‘Surrealist’ flavor of King’s work — its frequent recourse to the marvelous, its associative movement and its esthetic of surprise, often abusively identified with Surrealism proper — does a disservice to King’s less well-documented devotion to craft. Comparisons to John Ashbery’s meandering lyricism are hardly more satisfying. Robert Pollard’s angular rock-lyrics might offer a more fitting comparison: King winks regularly at Indie-rock cognoscenti, as in ‘Pollard’s kind of wrong’ and ‘I’m the Man Who Loves You’ (the title of a Wilco song). These references seem to occur more frequently than transparent allusions to the literary canon (despite nods to Stein and Pessoa). In my opinion, King’s indie-rock references detract from her poetic project, distract the reader from the vitality of her language. But Pollard’s language, although jagged and vivid like King’s, usually lacks the latter’s sensibility, her capacity for lightness of touch. Here is pitch-perfect:

^

We bachelors of approximate projects

go on to wing it and fly above the serenade. (‘Inhabiting Consciousness’)

^

Verbal economy is often inaccurately associated with a minimal lexical palette or a preference for the language of the everyday. Amy King’s lexical palette is enormous, but her language remains economical to the extent that it evacuates the flabby redundancies and laziness so common in everyday speech (and in the poets that adopt a related esthetic). King is aware of the artifice at the heart of her poetic idiom, an artifice rare and refreshing in the thoroughly colloquialized landscape of contemporary American poetry.

^

But King also reminds the reader that insofar as poetic language is constructed, its foundations do lie in a common language. Hence the idiomatic expressions which, while remaining immediately recognizable (‘Does my wording sound familiar? You’ve been here before,’ King writes in ‘The Lucky Lessons of Happenstance’), meld or mutate under King’s pen. The au revoir of walkie-talkies collides with a spilling beverage and becomes ‘malted alcohol running over and out’; someone’s lips almost follow the poet’s every whim, only to yield to disfavor, when ‘harmonica lips smile at my beck- / oning disgrace’ (‘Robert Pollard’s Kind of Wrong’ and ‘No Man’s Land,’ my emphasis). The familiar undergoes a kind of slippage or a series of swerves. Let’s call them evasive manoeuvers.

^

Although King arranges the poems of I’m The Man Who Loves You in alphabetical order, the final poem, significantly entitled ‘Yes, you,’ ends on a decidedly committed feminist note, a summoning to speech:

^

[...] I use

these places for my own constraints and as a reminder

there’s a storyteller within, if you’d only let her loose.

^

King addresses this summons both to herself (as other) and to the reader. I would suggest King should be read first of all as an unequivocally committed feminist: she often lampoons our inherited 19th-century conceptions of gender (see for instance, ‘This Is an Acting Marriage,’ quoted below, or ‘The Monster Within’). However, if she feminizes the internal storyteller, she by no means exclusively addresses a female audience (in other words, she feminizes your internal storyteller: yes, you). One of the collection’s most persistently recurring motifs is the inherent reversibility or interpenetration (!) of gender and sexuality:

^

Men who celebrate action

with their cocks, women with

their cocks [...] (‘This Is an Acting Marriage’)

I put on my long black dream and stepped into the world of women

to live among my female brothers who know how to grow

up on ink that occasionally vanishes [...] (‘I’m The Man Who Loves You’)

Doctors also resurrect hetero-others in the very best bearded

Ladies present. (‘I Used To Be Amy King’)

^

As many of the titles suggest, Amy King delights in disguise, and categories of gender and sexuality provide only a few of the masks with which she entertains her reader (once again, a characteristic trait of the baroque). A natural extension of this love of role-shifting is to apply it to the reader, by calling on him and her to exceed and resist whatever roles they have been given, as in the collection’s final lines. Feminism, as opposition to oppressively enforced roles, offers only one particularly compelling possibility of resistance.

^

But the political horizon of King’s collection does not exhaust the importance of gender and sexuality in the collection. King relentlessly flirts with her reader: eroticism is a privileged mode of interaction between reader and poem:

^

I know we can live without love from the waist up

and the kind that flows from up above, even horses

that speak our language, but the rest remains

a place we frequent with panty-laced desire and rely upon

for everywhere with bonus scenes as yet in production,

postoperative and pre-season. Like an apricot foam,

the hand that strokes a felt-like rose stem assumes

where it’s moving and when it’s moving in. (‘Mildly Free’)

^

Here as elsewhere, King’s poetry accomplishes a paradoxical synthesis of the cerebral and the sensual, viscera and intellect, summed up by the expression ‘scientific copulation in / religious veils’ (‘The Marriage of Birthdays’). Sex always involves an ironic ingredient, suggested here, for instance, by subtle comic allusions to the sexually ambiguous, male-and-female rose stem of the Romance of the Rose, not to mention Mr. Ed and Swift’s Utopic land of the Houyhnhnms. Such allusions suggest a sexuality filtered through layers of literary representation, complicated by culture, but no less invested with desire (indeed, all the more so).

^

Simon Dedeo, in a flash review of an earlier poem by Amy King, has written that ‘there is no way in which the language proffers some kind of promise of hidden sense — there is no hidden “key” — to be discovered.’[1] Dedeo rightly resists the interpreter’s reductive impulse, or points to King’s resistance to such an impulse. King indeed provides no ‘key’. But she does provide ‘keys,’ signposts to her reader that provide possibilities for the construction of sense, a variety of sometimes contradictory guidelines. Dedeo, like others who have compared her work to Surrealism,[2] unfortunately tends to reduce King’s convolution to the aleatory or the accidental. But such contrary perspectives on Amy King’s art — as concerted artifice and artful design which sustains multiple coherent readings, or as surrender to the inexhaustible and involuntary surprises of language — ultimately demonstrate the breadth of her appeal. For each reader, she is ready to ‘become / [her] own man again, ready, of course, to suit you’ (‘Swollen With Sun’).

[1] Simon Dedeo, Rhubarb is Susan weblog, , April 25th, 2005:

http://rhubarbissusan.blogspot.com/2005/04/amy-king-say-to-me-that-your-dreams.html

[2] Reb Livingston, The Happy Booker weblog, , July 7th, 2005:

http://thehappybooker.blogs.com/the_happy_booker/2005/07/poet_modern.html

Alexander Dickow

Alexander Dickow is a poet, translator, and scholar of French literature working towards his PhD at Rutgers University. You may find out more about him at Voix Off, his blog (http://www.alexdickow.net/blog/). He has published a review of four Kitchen Press chapbooks at DIY Publishing Blog

http://diypublishing.blogspot.com/2007/02/4-chaps-from-kitchen-press-review-by.html#links

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/dickow-king.shtml