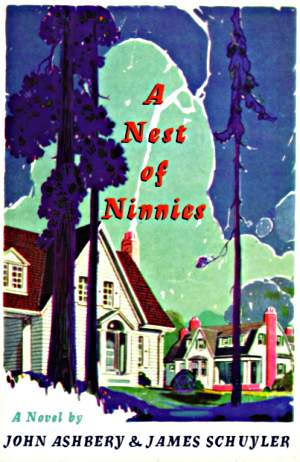

James Wallenstein

reviews the critical reception of

A Nest of Ninnies

by John Ashbery and James Schuyler

Ecco Press (1997), Hardcover: 191 pages, ISBN-10: 0880015233, ISBN-13: 978-0880015233

This piece is about 13 printed pages long.

There’s less to this than meets the eye.

― Tallulah Bankhead

1

In light of the considerable scholarship devoted to John Ashbery’s and James Schuyler’s poetry, it may seem odd that little ink has been spilled over their novel. Then again, A Nest of Ninnies, which is made from the stuff of novels ― characters, settings, episodes ― but not the stuffing ― the characters are stick figures, the settings interchangeable, the episodes without dramatic significance ― is itself an oddity, if a well-known one. Composed on Ashbery’s and Schuyler’s visits over seventeen years and originally published in 1969, it has been through three American and two British editions and is still in print. Though not uncommonly owned however it may be uncommonly read.

paragraph 2

Its impish title and studied prosaicness give A Nest of Ninnies the look of a conventional social satire; to encounter Ashbery’s famously difficult work in apparently accessible form may strike many readers as their best entrée to it. Indeed the opening prospective readers may glance at has an almost it-was-a-dark-and-stormy-nightlike familiarity: “Alice was tired. Languid, fretful, she turned to stare into her own eyes in the mirror above the mantelpiece before she spoke.”

3

We may think of the first line of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (“Alice was beginning to get very tired”) or of Emma Bovary looking at herself in the mirror and wondering why she married, though chances are we think of neither because we’re too busy doing what we do at the beginning of novels, gathering the information we think we’ll need to follow the plot: that Alice and Marshall live in a suburb fifty miles from New York which Alice longs for to the point of unhappiness, that she suspects Marshall is unhappy too but can’t interest him in this topic, that his preoccupation is with the leftovers they’re about to have for dinner and with a mislaid bread basket in particular. “The bread will be too dry to eat if we don’t find that basket soon,” he says. “Who knows, maybe I threw it out with the leftover Korn Kurls,” Alice replies. This seemed to wound Marshall, we are told.[1]

4

The wound is a figure of speech, as everything in A Nest of Ninnies is, though we don’t yet know it. Nor do we know yet that Alice and Marshall aren’t husband and wife as we’ve assumed from the situation, so that when “suddenly there [comes] a gentle tapping at the kitchen door” and Alice, instead of responding to it, descends to the cellar to shake the furnace ― it is on the fritz ― and “Marshall glide[s] across the room with careful steps to admit their visitor . . . a small, very pretty young woman,” we are alive to prospects of intrigue. It’s a matter of time before we see that the information we’ve been gathering is irrelevant, the intriguing prospects false.

5

How this recognition strikes us depends on our particular attitude towards the genre that A Nest of Ninnies is mimicking. Some readers will fly for the exits, others wonder along with Marshall ― and with the character Norris in James Schuyler’s next novel after A Nest of Ninnies ― what’s for dinner. But even for open-minded readers ― whether weary or wary of realism, receptive to comic experimentation, devoted to Ashbery’s or Schuyler’s poetics, or all of these ― the recognition of A Nest of Ninnies’ unconventionality, when it comes, comes by no means as an illumination. To see what a thing is not may be far from seeing what it is, and those who are determined to see it Ashbery-and-Schuylerwise have had enough to do with the poetry, which for all its slipperiness is aesthetically ambitious and so invites a serious critical response.

6

One can be less sure on the other hand how much analytical rigor to apply to a collaboration composed in the manner of a camp talent-show sketch, and bearing a similar resemblance to an inside joke. The exegete may himself become some kind of joker: joke-killer, joke-maker, fool, ninny. Those who don’t have to touch A Nest of Ninnies tend not to, and those whose projects are too comprehensive to avoid it ― namely David Lehman and David Herd ― don’t do much more than touch it. Their caution expresses itself in a genealogical impulse, a disposition to account for A Nest of Ninnies in relation to supposed antecedents in the history of the American or British novel. My contention here is not necessarily that Lehman and Herd are wrong, nor that A Nest of Ninnies is literary-historically sui generis (It isn’t.[2] ) but that it is better, truer to the work and more hospitable to our appreciation of it, to approach A Nest of Ninnies as a performance, an object that has its ultimate significance in its articulation rather than through reflection.

7

Of course, A Nest of Ninnies is a book, and books are monumental. To make a non-monumental book seems counterintuitive if not perverse. Why not just talk? This is essentially what Ashbery and Schuyler are doing, writing not in the manner of talking but in the spirit of talk, and jesting with the difference. They take their title from Robert Armin’s Jacobean jest book. It may be that Ashbery and Schuyler’s Nest’s proper antecedent, with which it has little else in common, is its namesake.

8

David Lehman signals an intention to reckon seriously with A Nest of Ninnies. “It is worth pausing over . . . the comic tour de force [Ashbery and Schuyler] began that day and completed seventeen years later,” he writes in a section of The Last Avant-Garde on The New York School’s members’ artistic collaborations. But this intention miscarries. The pause is all of two-and-a-half pages, and analysis of the novel quickly gives way to celebration of literary teamwork:

9

The style of arch ventriloquism that Ashbery and Schuyler adopted in A Nest of Ninnies had the virtue of allowing each of the two to escape from his personality, to lose himself in his work, in the sense commended by T.S. Eliot, who had argued that “poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion” and that “only those who have personality and emotions will know what it means to want to escape from these things.” Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about A Nest of Ninnies is that the two poets have dissolved their own personalities and merged so entirely into a common style that it can be said that the book’s author is neither Ashbery nor Schuyler but a third entity fashioned in the process of collaboration.[3]

10

Lehman’s book is a group portrait, not a consideration of every work of every New York-School associate. His interest is in A Nest of Ninnies’ place in Ashbery’s and Schuyler’s biographies, and to expect a detailed reading of the novel from him would be unfair. Still his uncertainty about how to take A Nest of Ninnies other than as a collaborative feat leads him to a fit of cliché-spouting that not only avoids the challenges the book poses for prospective readers but may also blur the portrait: the Thomas Carlylean cliché of work allowing the worker to escape the burden of his personality and emotion is yoked to the especially demagogic T.S. Eliot cliché that the personality and emotion of poets are truly burdensome to themselves because they are truly poets which is yoked to the Christian liturgical cliché that from the conjugal union of two personalities arises an autonomous, mysteriously unburdensome third. Of this new third personality nothing is broached, and it is hard in any case to imagine Carlyle, Eliot and the Church fathers as this Ashbery-Schuyler hybrid’s cultural ancestors.

11

In light of his attention to the uniqueness of the method of A Nest of Ninnies’s composition, Lehman’s heavily genealogical approach in the single paragraph that he does give to the text is curious.

12

Character is a subordinate function of dialogue in A Nest of Ninnies, and dialogue is a celebration of the American suburban vernacular, which is accurately mimed in the spirit not of ridicule but of “respect for things as they are,” in Fairfield Porter’s phrase. As in the novels of Henry Green, which Ashbery had made the subject of his master’s thesis at Columbia, A Nest of Ninnies is 90 percent dialogue. The novel’s technical debt to Green is great, but its tone couldn’t be more different. In his master’s thesis Ashbery has saluted the “strangeness and the strange despair” he found in Green’s novel Concluding, which differed from Kafka’s despair inasmuch as Green “still finds an occasional and nervous beauty in the world he is describing.” Green’s despair and “nervous beauty” are conspicuously absent from A Nest of Ninnies.”[4]

13

If indeed A Nest of Ninnies is written in the spirit of respect for “things as they are,” it may be the better part of taking it on its own terms to try to describe what it is rather than what it’s like. And if the collaborative nature of the project that created it, its origin in social rather than private experience, is the source of its distinction, why look for antecedents from a canon made of texts produced by a single author? A Nest of Ninnies may well be technically indebted to Henry Green’s work (though Schuyler’s Alfred and Guinevere [1958] is also told mainly through dialogue). But would we enhance our understanding of the one by reading the other?[5]

14

As it happens, Green’s novels typically contain proportionally more description than does A Nest of Ninnies. The question in any case is whether their sharing a formal attribute means that this attribute provides a fruitful basis for comparison. If X uses his spatula for flipping fried eggs and Y uses his spatula as a badminton racket then what, beyond occasioning us to marvel at the spatula’s versatility, does their both having spatulas indicate? Even if X had bought Y his spatula, even if the idea of a novel in dialogue came to John Ashbery from his knowledge of Henry Green’s work, the relation would be incidental to the natures of the things related. Green’s are realist novels in which the conventions of prose fiction such as attributed speech are mimetically deployed. A Nest of Ninnies is anti-mimetic and unconventional.

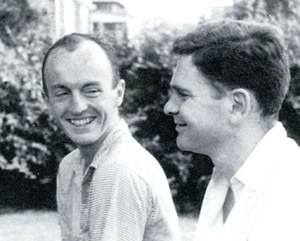

L to R: Frank O’Hara and

James Schuyler in 1956

15

The specific nature of this anti-mimesis will be taken up later. Suffice it to say here that when Lehman gives up the hunt for the novel’s literary precursors he finally offers an insight that recognizes the novel’s particularity: “A collaboration so faithfully sustained in the face of such frequent and prolonged interruptions,” he writes, “cannot but be seen as the fruit and testament of a friendship grounded in love ― or even as a form of literary lovemaking.” The circumstances of the novel’s composition testify to the inspiration that Ashbery and Schuyler each drew from the other’s company. A Nest of Ninnies in other words springs like a Platonic dialogue from companionship and from speech. Henry Green or no Henry Green, how else was this speech to be rendered? Lehman concludes his treatment of the text just when he seems poised to engage it.

16

Situating A Nest of Ninnies in literary history and citing its influences also consumes a good deal of David Herd’s discussion of it in John Ashbery and American Poetry, a surprising turn given the book’s emphasis on Ashbery’s poetry’s engagement with its own occasions: “Ashbery’s intention in aiming to write the poem ‘fit’ for, or belonging to, its occasion,” Herd says, “is to achieve a poem appropriate to the occasion of its own writing.”[6] In his account of A Nest of Ninnies, however, Herd abandons this sense of Ashbery’s poetics of contingency for a broad typology; it’s not A Nest of Ninnies’ extraordinary relationship to the circumstances of its composition that interests him but instead its generic relationship to the American novel:

17

A Nest of Ninnies is hardly a novel at all, but, as certain episodes indicate, a parody of the great American novel. It is a far cry, for instance, from the disastrous fate of the Pequod to the delayed return of some of the party from Captain Hanson’s boat-trip round a ‘remote and gloomy portion of the Everglades.’

But if it subverts the basic conventions of the novel . . . and if it parodies the picaresque form of the great American novel in particular, A Nest of Ninnies is, in its own ironic, understated way, concerned throughout with the question of American identity which is the subject of such questing works. Indeed, one would say that Americanness was the novel’s theme, were it not for the fact that it is so integrally a function of its occasional structure.[7]

18

If Nest of Ninnies were a poem, Herd would be attuned to its discontinuities, ready absurdities, its ludic rather than lucid impulses. He chooses instead to classify it in the broadest terms. Granted, A Nest of Ninnies can be characterized as parodic, though if this parody is indicated as Herd says by certain episodes, it’s worth pointing out, so as not to ascribe to the episodes a uniformity that they haven’t got, that the basis of the parody isn’t in the episodes themselves. Granted, the characters travel and as this travel is an undisguised excuse for smalltalk about sightseeing, the novel can be said to parody the quest motif and the object of this parody be seen as the so-called great American novel, though this is commonly said about Gravity’s Rainbow for example and Carpenter’s Gothic, books that A Nest of Ninnies seems no less different from than the classics of which it is said to be a parody.

19

And granted, since Ashbery and Schuyler are both American and fill the novel with domestic and foreign characters some of whose dialogue trades in commonplaces about national types, Americanness must be a theme (assuming that Nest of Ninnies has themes in a conventional sense), or would be, “were it not for the fact that it [Americanness] is so integrally a function of its [A Nest of Ninnies’] occasional structure.” Never mind Herd’s earlier claim that Ashbery’s occasional sensibility derives from his reading of Pasternak, when a concept as elastic as national character is identified as an undefined integral function of an undefined occasional structure, who’s to say otherwise, that national character isn’t a theme ― or is but that theme is Swissness or Canadianness ― when to do so could only redden the herring?[8]

20

Herd asserts that Nest of Ninnies “subverts the basic conventions of the novel,” and proceeds to read it as still participating in those conventions in order to parody them: it must be thematic because novels are, must be personified because novels are, must be national because novels are. What Herd seems to mean by “subverting the basic conventions” is something closer to mocking them: to understand A Nest of Ninnies in terms of the history of The Novel requires that those conventions still apply. This is what would make them “basic.”

21

The dialectical somersault Herd turns in his discussion of “the stark, comically disturbing personality shifts” that “major characters undergo” in A Nest of Ninnies demonstrates this confusion:

22

All of which instability might seem to undermine the very possibility of identity, were it not a wry affirmation of [a] very American sense of self . . . . Twain makes the point much more comically [than Charles Olson] with Huck Finn, whose journey down the Mississippi does not cause him to develop... but instead sees him pass through a series of radical shifts of identity, each new necessary act of imposture amounting to a new Huck. Huck’s identity, in other words, is not stable, coherent or developing. In fact it is a function not of Huck at all, but of the situation in which he finds himself. He is discernible in what he is not.[9]

23

It seems to me that Huck is instead discernible in what he was, discernible, for all the incongruity about him late in the novel, because the conception that he ― his name ― represents is still coherent. We may lose our affection for this representation, and find it less convincing than we had. Even so, we retain an essential image of him. Huck’s identity resides for us in a general idea of his presence in an imaginary world, a sensuous idea of his appearance, voice, bearing and so forth, of his physical rather than moral being. This idea, this image, is fixed. If, late in the novel, Twain had endowed Huck with attributes that struck us as incompatible with our image of him ― a Veronica Lake hairdo, for example ― the description, for all its hypothetical charm, would fail. Unable to square it with our image, we would withhold our belief ― as we may withhold it from scenes late in Twain’s novel ― and keep to our first idea, which is the basis for Huck’s imaginary identity and for Huck’s being discernible in the name “Huck.”

24

Herd’s rhetorical motive is plain enough. Casting Huck’s identity as protean ― “a function not of [himself] at all, but of the situation in which he finds himself” ― allows Herd to attribute to national literary character, of which Twain’s novel is of course a touchstone, what he regards as a similar quality in the Ashberian lyric speaker, whose American and democratic credentials Herd would thereby assert. The assertion, and with it, the relationship to Huck, may be valuable to a consideration of Ashbery’s poetry. Where the matter of characterization in A Nest of Ninnies is concerned, however, the portrayal of Huck is irrelevant. There is no characterization in A Nest of Ninnies. There are characters of a sort, personages assigned names, ages, and social positions that nevertheless do not distinguish them. They are vacant. Their voices, even when they speak as it were in character, are the authors’. Their lines ring epigrammatic even when signally trivial.

25

This lack of characterization would illustrate Herd’s point about characters’ being “functions of the situations in which they find themselves” if the situations themselves were revealing. They are instead as exuberantly superficial as the characters. There are, picked up or dropped on a whim, preparations and eventualities, rivalries and romances, all of no consequence. The Novel, I suppose, has developed its particular conventions to enable it to mean as much as possible. Ashbery and Schuyler’s game is to apply these conventions and to mean as little as possible, not in order to mock the conventions ― at least not mainly in order to mock them ― and not to produce nonsense ― there’s very little by way of nonsense in Nest of Ninnies ― but for the high childlike pleasure of saying more than they mean, a common enough pleasure in conversation but one that has been almost lost to prose.

26

We are unaccustomed in novels to so much saying so extravagantly and lightly said. The novelist is captive to his or her own device; each line must chime with the rest to earn its keep. Tolstoy belittles Shakespeare for being “a phrasemaker”; F. Scott Fitzgerald tells us to murder our darlings. Meanwhile, here are Ashbery and Schuyler’s ninnies ― the word derives from “innocent” ― on the boat-trip to which Herd refers:

27

“I have a feeling there’s a lot of good lurking in Claire,” Victor said, eyeing the flooded though sluggish stream.

“Lurk is the word,” Alice said. “Say ― don’t you think Captain Hanson is kind of a funny name for an Everglades guide?’

“You mean the captain part or the Scandinavian last name?” Fabia asked with a brisk little yawn. “Isn’t that a drowned alligator over there? Next to that mangrove tree, I mean,” she finished petulantly for no apparent reason.

“To your left,” Captain Hanson said, “you will see a drowned female alligator ― another result of the recent storm. Since it is the mating season, this is especially tragic.” He spoke with a marked Hoosier accent.

“I guess the flood was too much of a good thing for the alligators,” Alice said.

“I look,” Claire Tosti said, “I look ― and all I see is a succession of the costliest pumps and handbags.”

“Dead or alive,” Captain Hanson said, “these alligators are the property of the state of Florida.”

Claire emitted a piercing shriek that immobilized the other passengers of the Maid of the Marshlands.

28

Darlings, darlings galore ― camped-up clichés, spicy nonsequitirs, inside jokes, and, out of the blue, affectionate gems like Fabia’s “brisk little yawn.” And why not? With collaboration freeing Ashbery and Schuyler from serving the novel-reader with plot and character as the novel-reader is wont to be served, each’s reader being the other, why not nurture their darlings? The unit of measure in A Nest of Ninnies is the unit of measure in speech: not the line, paragraph, scene, or chapter but the phrase, the variable length of a single thought, whether dialogue or description.

29

For the reader of a realist novel, the dialogic and descriptive components of the first line of the most recently cited passage (“‘I have a feeling there’s a lot of good lurking in Claire,’ Victor said, eyeing the flooded though sluggish stream.”) would be unified as aspects of the characterization of Victor, which would itself be an element of the plot. Victor’s utterance might tell us about Claire and would surely tell us about himself. The descriptive part of the sentence would also tell us about Victor, about what he looks at and how, as well as about the landscape. The relationship between what Victor said and perceived would be aspects of his depiction and of the plot. The quality of the narration would be an ancillary consideration.

30

In the case of the Nest of Ninnies reader, however, neither Victor’s budding attraction to Claire nor the fact of his expressing it to Alice as he does nor what these reveal about his character per se is of interest. The tone and style of the phrases, animated by the pretext of character and dramatic situation, are everything. Victor is certainly a ninny, but ninnydom is general and more or less benign, and resides in language. What we might otherwise deem an indication of disingenuousness in Victor ― in the character called “Victor,” that is ― registers as a kind of semantic rust on the words attributed to him, a mechanical encrustation on the human of the humor-producing variety. Exclamations in a cartoonish banal nineteen-fifties vein resolve in reflexive mock-bathetic punch lines, in a movement not from the exalted to the commonplace but from one kind of absurdity to another, as in the already quoted “‘Isn’t that a drowned alligator over there? Next to that mangrove tree, I mean,’ she finished petulantly for no apparent reason,” and “‘To your left,’ Captain Hanson said, ‘you will see a drowned female alligator ― another result of the recent storm. Since it is the mating season, this is especially tragic.’ He spoke with a marked Hoosier accent.” Sometimes the reflexive jests are in the dialogue, as in

31

“Betty, there’s a Mr. Hofstetter here to see Irving. He says he has an appointment.”

“I see,’ she said, and replaced the phone. “Please sit down ― Miss Burgoyne will be with you in a moment. Exactly how do you spell Hefstetter?”

“Two t’s,” the man replied after a few moments’ hesitation. “Is Miss Burgoyne in Production?”

32

Instead of setting the words they surround in context by indicating their attribution to a speaker, quotation marks here betray a contextual void. They serve, not as italics would, to activate another non-contextual meaning of the words, but to highlight their own felicitous triviality.[10]

L to R: Schuyler,

Ashbery, Koch

33

To read their prose closely, to attend to its effects as to a poem’s, is for better or worse to follow the lead of the New York School poets themselves. In a contemporary review of Schuyler’s Alfred and Guinevere, a somewhat more conventional and serious novel, Kenneth Koch writes that

34

The whole aim of the book is poetic ― as though its author had set out to write a novel which would never violate for a moment his ear, his eye, his sensibility. The problem for poets writing novels is that they become bored (and so do readers), but Mr. Schuyler has transferred the excitements of poetry to his prose; something (witty or prosodic) is happening at every second . . . . Schuyler’s language makes one aware not only of what it describes, but also of language itself ― of the word as a word among words ― as poetry does, or should.[11]

35

And in Ashbery’s introduction to a new edition of the same book, he writes that in all his fiction “Schuyler is mainly concerned with language used as a precision tool to further the ends of poetry.” Ashbery’s own novelistic aesthetic may possibly be gleaned from snatches of his few reviews of novels. In an adulatory review of Giorgio de Chirico’s novel Hebdomeros, he says that

36

Everything about Hebdomeros is mysterious . . . . The novel has no story, though it reads as if it did . . . . [de Chirico’s] language, like his painting, is invisible: a transparent but dense medium containing objects that are more dense than reality. What gives Hebdomeros a semblance of plot and structure is the masterful way in which leitmotifs are introduced, dropped and reintroduced where one least expects them.[12]

37

He admires Michel Butor’s La modification:

38

It is perhaps Butor’s talent for minute observation which renders La modification so singularly attaching. It is true that his final message is one of agony... But the richness of detail (including almost humorous descriptions of the minor ennuis of the trip and dazzling evocations of scenery and the play of light and shadow which at times suggest a painting by Degas or Carrière, or a dim drawing by Seurat) causes one to put down the book feeling rewarded rather than aplati.[13]

39

and compares Witold Gombrowicz’s heavily plotted Pornografia unfavorably to Henry James’s thinly plotted The Sacred Fount, “an infinitely more subtle and finally horrifying account of people living their lives in and through the lives of others.”[14]

40

Here and there, in offhand statements of quixotic preference ― in the exclamation “(snore)” that the mention of Saul Bellow occasions in one of Schuyler’s letters to Ashbery, in Schuyler’s recommending George Ade’s Fables in Slang (the slang here is late 19th-century American midwestern) over a series of adventure stories called Pink Marsh by the same writer[15] ― we begin to get the impression of a consensus among members of the New York School that the interest of a novel lies in its language per se and that novelists should use the means available to them, the codes and conventions of the form, to achieve what would typically be considered poetic effects.

41

It is easy enough to see reasons for this beyond Ashbery’s, Koch’s and Schuyler’s allegiance to poetry. The plot-driven novel is first and foremost a pastime, an escape, and so presupposes that the default-position of consciousness so to speak is an unhappy one from which we desire distraction. Such an outlook jars with the New York School member’s approach to life, with its good cheer and great curiosity about the ordinary, and to art, which finds the relationship between the fact of attention and the thing attended to limitlessly engaging.

42

The Novel, that nest of ninnies, with its teleology, strategies of deferral, semantic magnifications, windless closures and moral dispensations ― The Novel, which has been “over” for so long and which would seem to be the least hospitable form to a New York School sensibility, must to this sensibility for this very reason have been enticing. To toil under such freight, reading and writing in friendship where so many have read and written in hiding, was, as the aimless pleasures of A Nest of Ninnies attest, freedom itself. Ashbery, borrowing a phrase from Henri Michaux, calls poetry “the big permission.” And Schuyler, in a poem entitled “What?” asks “What is a/ poem, anyway?”

[1] John Ashbery and James Schuyler, A Nest of Ninnies, New York: EP Dutton, 1969, p. 11.

[2] The French Surrealists and Ronald Firbank are both influences. In a 1966 Book Week review of an English translation of Giorgio de Chirico’s Hebdomeros entitled“Decline of the Verbs,” (reprinted in Selected Prose of John Ashbery, Eugene Richie, ed. Ann Arbor: 2004 pp. 88-92) Ashbery identifies, in addition to the work under review, certain works by Breton, Élouard, and Aragon as constituting “the most powerful single influence on the twentieth-century novel.”

In 1997 in response to an interviewer’s observing that A Nest of Ninnies “is very Firbankian” (“Building the Nest of Ninnies: A Conversation with John Ashbery,” Lambda Book Report, Washington: Nov. 1997, v. 6, no. 4. pg. 24.) Ashbery replied, “Both of us had read Ronald of Firbank and, of course, admired him. This summer I decided to reread all of Firbank, and I was surprised that the book is more indebted to him than either of us realized. It’s Firbank refracted through an American lens ― two lenses, in fact.” In his essay on Frank O’Hara, Ashbery credits O’Hara with having “allowed me to see what a major writer Firbank was.”

[3] David Lehman, The Last Avant-Garde, NY: Doubleday, 1998, p. 82.

[4] Lehman, p. 81-82.

[5] He [Mr Rock] went slowly and was overtaken by George Adams, the woodman, going up for orders.

They did not speak at once, went on together down the ride in silence, between these still invisible tops of trees beneath which loomed colourlessly one mass of flowering rhododendron after another and then the azaleas, which, without scent, pale in the fresh of early morning, had not begun, as they would later, to sway their sweetness forwards, back, in silent church bells to the morning.

The man spoke. “It’ll turn out a fine day yet,” he said.

“Yes, Adams,” said the other.

They walked on in silence.

“How’s your wife, Adams?” Mr Rock then asked.

“Why I lost her, sir, the winter just gone.”

Mr Rock said not a word to this at first. “I’m getting an old dodderer,” he ventured in the end, sorry for himself at the slip.

“You’re a ripe age now,” George Adams agreed.

He never offered to help carry those buckets, the man reminded himself, because whatever the position Mr Rock had once held, this long-toothed gentleman did his own work now, which was to his credit.

“Yet I feel not a day older,” Mr Rock boasted.

“It’s my legs,” the sage added, when he had no reply.

There was another silence. It was too early yet for the birds, or too thick above, because these were still.

“Nothing anyone can do for the bends,” Adams said at last, out of an empty head.

At this instant, like a woman letting down her mass of hair from a white towel in which she had bound it, the sun came through for a moment, and lit the azaleas on either side before fog, redescending, blandketed these off again; as it might be white curtains, drawn by someone out of sight, over a palace bedroom window, to shut behind them a blonde princess undressing.

— Henry Green, Concluding, London: Penguin, p. 2.

On the subject of Green’s influences, in his introduction to Loving, Living, and Party Going, John Updike writes that Green’s “style’s source, strange to say, or at least the source of its innovative courage, is Arabic, as transmuted to English by Charles M. Doughty in his Travels in Arabia Deserta (1888). Doughty’s style originated, he wrote to his biographer, in ‘my dislike of the Victorian English; and I wished to show, and thought I might be able to show, that there was something else’. Arabic, as it was absorbed by Doughty on his travels, was a language of the ear, spoken by illiterates, and it is the alogical linkages of spoken language, with its constatly refreshed concreteness, that inform such sentences from Arabia Deserta as

Never combed by her rude master, but all shing beautiful and gentle of herself, she seemed a darling life upon that savage soil not worthy of her gracious pasterns.

No sweet chittering of birds greets the coming of the desert light, besides man there is no voice in this waste drought.”

[6] David Herd, John Ashbery and American Poetry, Palgrave: New York, 2000. The passage continues: “His [Ashbery’s] concern is with the time, place, situation, and circumstances of the poem itself. As he put it in an interview, ‘the poems are setting out to characterize the bunch of circumstances that they’re growing out of and a day might be said to be the basis for a poem’.” (p. 10)

[7] Herd, p. 63-4.

[8] Herd, p. 10-11. Herd sees Pasternak as both an influence on and an object of parody in Nest of Ninnies specifically: “Nothing, it might be observed, escapes the ironic touch of Ashbery and Schuyler in this novel, the instability of their characterisation parodying that most sacred of their shared texts, Doctor Zhivago, he central characters of which, as Stuart Hampshire observed, are not ‘endowed with . . . rounded naturalness nor are their lives steadily unfolded before the reader’.” Herd, p. 64.

[9] Herd, p. 64.

[10] This triviality may of course be regarded as celebratory “of the American suburban vernacular,” as Lehman contends; or, more perversely, of banality and homogeneity; or as sending up the literary objectivism of Robbe-Grillet and his school and/or, for that matter, the novel of suburban misery of Cheever, Richard Yeats, Updike, the other O’Hara as well. But however regarded, its temper seems epiphenomenal to A Nest of Ninnies.

[11] Kenneth Koch, “Poetry as Prose,” in Poetry, v. XCIII, No. 5, February, 1959, pp. 321-23.

[12] Selected Prose of John Ashbery, Eugene Richie, ed. , op cit., pp 88-92.

[13] Ibid, p. 17.

[14] Ibid. p. 107. Compare Rebecca West’s recapitulation of The Sacred Fount’s plot: “A week-end visitor spends more intellectual force than Kant can have used on The Critique of Pure Reason in an unsuccessful attempt to discover whether there exists between certain of his fellow-guests a relationship not more interesting among these vacuous people than it is among sparrows.”

[15] Both references are in a letter to John Ashbery of 7/9/66. in Just the Thing: Selected Letters of James Schuyler, William Corbett, ed. Turtle Point Press: New York, 2004.