James Stuart

reviews

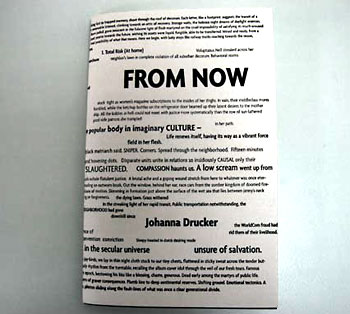

From Now

by Johanna Drucker

Cuneiform Press, 2005. 48pp, 22 x 14 cm. Edition of 200, signed by the author. US$15

This review is about 7 printed pages long. It is copyright © James Stuart and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

It is refreshing to review a book where one is not simply reviewing the writing but also the book itself, language and its material form. In this case, the work is by seminal book-artist, academic and author Johanna Drucker, and it has been beautifully published by not-for-profit fine-press Cuneiform Press, run out of Buffalo, NY by Kyle Schlesinger.

2

What excites me is how From Now embodies the philosophy of language-as-object; rather than considering books as pro-forma for the writing they contain, the physical and typographical structuring become part of the reading experience and an extension of the author’s intended meaning and style. In this publishing paradigm books are sensuous, visually stimulating and intellectually engaging objects. They are not just a vessel for language; they are a language unto themselves.

3

Within the poetry world, this is rare. In Australia, Vagabond Press creates limited run editions of its books, carefully typeset (often by poet-typographer Chris Edwards) while artist Kay Orchison creates cover artwork (generally photo-media or digital scan works). A recent discovery I made was award-winning publisher Canadian Gaspereau Press who produce a variety of Canadian literary publications (poetry included).

paragraph 4

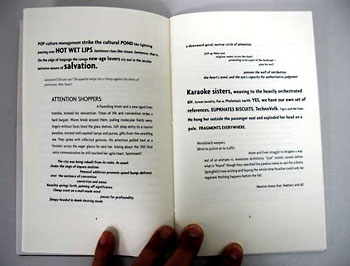

Like Cuneiform, Gaspereau operate superseded printing technology, which they use to great effect. Their publications are generally offset prints that are smyth-sewn and bound into card covers and then enfolded in letterpress-printed jackets. In the case of From Now Schlesinger informed me that the covers were printed on a Vandercook 4 proof press from photopolymer plates. The text was laser-printed. Drucker typeset the work herself.

5

What differentiates the likes of Vagabond, Gaspereau and Cuneiform from dedicated book-arts publishers such as Electio Editions and Wayzgoose Press here in Australia or Drucker’s own Druckwerks[1] is affordability and simplicity. While such book-art can sell for prices ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars, all three presses discussed here produce trade editions that, while often limited in their print-run with a degree of hand crafting involved, overwhelmingly subscribe to the tradition of the book as codex. They are sold at prices comparable with other commercially printed poetry books. Cuneiform also produces limited posters and cards. It is a publishing model that sorely requires replication within the poetry world for many reasons, some of which will hopefully become apparent over the course of this review.

|

6

There are a number of precedents for publications in this ilk, dating most directly back to the late 19th century when poet, designer and publisher William Morris established Kelmscott Press, while in Paris a strong culture of livres d’artistes emerged[2]. Bodley Head Press is another example cited alongside Kelmscott by Jerome McGann in Black Riders: the visible language of modernism.

7

McGann also points out the strong influence this fine press movement had on Ezra Pound who published A Draft of XXX Cantos in a limited edition of 200 through Nancy Cunard’s Hours Press; like Charles Baudelaire, who was fastidious about the production of his books, Pound was intimately involved in the typesetting and printing of the Cantos: ‘The Cantos sums up the power and authority of the most elementary forms of language, its systems of signifiers as historical artefacts. [...] Through book design Pound makes an issue of language’s physique, deliberateness, and historicality.’[3]

8

This approach mirrors the pre-Raphaelites’ print-based efforts, with which Morris was associated, to restore some of the individuality of medieval manuscript culture, which in their view had been subsumed by the overwhelming uniformity of the publishing industry at large. It is the conundrum of written versus printed English. It is also an apt segue to Drucker’s From Now since here is a book overwhelmingly concerned with historicality, namely the media-, pop culture- and news-saturated NOW.

9

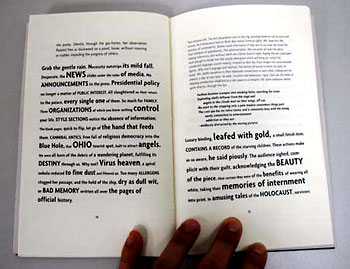

Falling perhaps more comfortably under the rubric of “experimental writing” than poetry per se, From Now is a postmodern parable centred on the lives of some nine archetypal characters: Goffman ‘our heroic figure’, Ned and Nell ‘the lovers’, Lili ‘pleasure vixen, demon lover, the other of all women’, Atom and Even (as in Adam and Eve) – to name a few. As the inclusion of Adam, Even and Lili suggests, this parable has biblical roots.

|

10

It begins with the fall: ‘The days of privilege are past. Now comes the bitter difficulty, edged and mordant.’ (p.1), then later: “ATTENTION SHOPPERS: / a foundling Atom and a new-aged Even tremble, brinked for reinvention.’ (p. 4). What Atom and Even have tumbled into is not so much a world of sin, as the material world of Madonna’s Material Girl: neon, lust, concrete, scents, shopping, broadcast media, billboards, brands, mortality... ‘No heaven, no hell, just the earthly distribution of particulars, topographically precise. [...] Gelatin substances, gentle as old rain, came off the supermarket shelves at a great rate on the day of the solstice. Stopping up the cracks in the universe, the malleable substance of memory refused to hold its shape. Sticky data held fast.’ (p. 30)

11

But unlike Eve, Drucker resists the temptation for facile narrative. Instead she proffers a series of intense, staccato, image-saturated interconnected bursts of language, in which the story is at best a loose thread woven into chapters; three distinct voices emerge and interlace.

12

Drucker has typeset the book herself, a rarity in the writing world but not the world of artist’s books. She uses ‘Agenda Light, Medium, Bold and in sizes from 10 to 24, with italic added.’ These varying font-sizes and weights are deployed to great effect; each of the three voices is designated by its own typographic strategy in a process of explicitly visual experimentation.

13

VOICE 1 is that of the omniscient but disembodied narrator, recounting the internal and external lives of the archetypes as they move through a variety of physical and psychological landscapes, many of which have a filmic quality to them. The text is set in Agenda Light and Medium, generally indented and justified, sometimes bold or italic. Font size is 10-12pt:

14

Goffman, the marginal figure, sees himself as the hero, standing on the sands in the early morning wind, leaning towards the surf. Behind him the group breaks up. One woman more melodramatically inclined than the rest, wrapped herself in a vividly patterned quilt, reminiscent of a houri’s shawl, some leftover prop from the harem sequence. (p. 24)

15

VOICE 2 enounces fractured remnants of pop-culture, advertising and news broadcasts, a mediated and claustrophobic copy-and-paste of images parading as lived experience. Set in bold, left-aligned, varying from 12-24pt, its words and sentences are occasionally upper-case:

16

YOU with your NIGHTCAP and me with my GUN. Crawling through underground Atlanta while the Sultans of Swing performed the rugged banjo tunes of no one’s youth. Coke had sponsored the event. Legitimate enough. WE NEED OUR UNDERWRITERS in advance of our undertakers. (p. 11)

17

VOICE 3 is perhaps the most identifiably poetic, displaying an unconventional and experimental lyric sensibility. It is set in traditional line-breaks in bold-italic, 10-12 pt:

18

They play with their investments, buying anything but time.

Parcels of property eked from the ravages of ages and agents avarice

to stand the text of

He slapped her –

news comes between them, a giant yawn, spitting out

details of events for which they think they have no use.

19

While my categorisation is neither watertight nor comprehensive, since other voices exist and there is some typographical seepage between them all, especially as the book progresses, it does serve as a means through which to explain the work.

20

As previously noted, Drucker interlaces these different voices and, therefore, typographic styles throughout From Now; in reading the book, I found myself in a constant state of perceptual flux, as my attention hovered between contrasting modes of linguistic and visual representation. It was an experience akin to flicking rapidly between television channels, but not television as we know it.

21

That image may seem forced, given the media-based imagery the book draws upon, but it is an apt comparison since Drucker's book is a literary work, but not as we know it; it resists the standard reading patterns associated with both prose and poetry. Without such close consideration to its material formulation, such writing, in my opinion, can often fail.

22

Drucker’s typographical approach, and Cuneiform Press’s realisation of it, brings the reader into contact with the specific modes of literary representation she engages. It is heavy with its own materiality, as McGann might say. Marjorie Perloff echoes this framework when speaks of the ‘poetics of non-linearity or post-linearity’ which ‘are as visual as they are verbal; they must be seen as well as heard, which means that at poetry readings, their scores must be performed, activated.’[4]

23

What emerges through Drucker’s activation of language is an extremely bleak view of a fallen and crumbling world, beset by sensual overload (whether erotic, consumerist or onanist and self-obsessed). Concurrent is a fundamental spiritual and emotional indifference to the death and suffering that surround it. Or perhaps it is an inability to comprehend these phenomena since they are always other:

24

Grab the gentle rain. Necessity outstrips its mild fall. Desperate, the NEWS slides under the radar of media. No ANNOUNCEMENTS to the press. Presidential policy no longer a matter of PUBLIC INTEREST. All slaughtered on their return to the palace, every single one of them. So much for family. (p.34)

|

25

As Drucker herself professes, From Now feeds off the news in all its chaos, simulated and dissimulated through the media, as it reverberates throughout the ‘MOLECULAR LIFE’ of we who inhabit this earth. In Drucker’s writing, the materialist world of late capitalism is on a crash course with fate. It is a world of surfaces that will freeze over: ‘THE BILLBOARD UNIVERSE, once spatial, now glacial, goes rigid with cold PIXELS stuck in their tracks, floss between their teeth. Every space occupied.’ (p. 46)

26

Perhaps what is being exhorted is not so much the end of the world but the rejection of its self-interested, dehumanising and didactic representations through the media and its grand ideologies: ‘Opulent Nell, go back into your cell and contemplate the possible rewards of the afternoon, rather than the afterlife.’ (p. 33) But other than such fleeting, sensuous moments of clarity, I see little of the ‘possible scenarios upon which optimism might be based’ that she alludes to through a statement in the book’s end credits.

27

Ultimately, I am left out in the cold by Drucker’s own representational strategy. Her language-object, for its virtuosic achievement as a piece of writing, feels removed from lived experience, laden with a very particular, highly political and anti-lyric world-view. None of these qualities are negatives but Drucker’s world-view does not grant agency and circumstance to the denizens it portrays. Instead, they are explicitly relegated to the status of archetypes and the world is flattened into a cinematic disaster.

28

This is a deliberate strategy, of course, and a visionary reaction to the problematic situation in which the developed world’s hyperreal “heaven” daily rubs up against the other-one’s hell, but only through the fault line of broadcast technology (with all the vested interests involved). Maybe it is not “us” who needs to be humanised, but the “other” who exists at the sharp end of the camera.

29

These are scenarios that are, if not specific, then at least highly relevant to understanding lived experience in the 21st century. Equally important are other issues that Drucker raises, and which I have not adequately addressed here. Among them are the questions concerning spirituality and religion that permeate the book and which certainly merit more attention.

30

Perhaps it is just that From Now lacks the deftness of touch and sense of play (though there are puns aplenty throughout the book) of some of Drucker’s other works, most notably The History of the/my Wor(l)d (1990) in which lyrical fragments interleaf more direct phrasings and diagrammatic elements. But there is a great craft to be observed here and a benchmark is set in terms of multi-voice experimental writing. A benchmark is set by Cuneiform Press’s production too and I hope to see/read others rising to meet it.

|

James Stuart is a Sydney-based poet, editor and new media artist. He has been the recipient of several awards, including most recently the 2004 Newcastle Poetry Prize’s New Media category. His new media poem ‘In Between Berowra’ was featured as part of the Berowra Visions: Margaret Preston & Beyond exhibition at Macquarie University Art Gallery in 2005. He is currently completing a Masters of Creative Arts at the University of Technology Sydney, examining poetry as a material object. |

[1] As well as countless others overseas – my immersion in the field of books arts is limited.

[2] Johanna Drucker adroitly differentiates between livres d’artistes, which were the machinations of editors, and artist’s books, artist-led initiatives, in her tome, A Century of Artist’s Books.

[3] McGann, Jerome, Black Riders: The Visible Language of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. p.80 For a more contemporary assessment of this tradition in America see Schlesigner’s article on Robert Creeley in Jacket 31: http://jacketmagazine.com/31/rc-schlesinger.html.

[4] Perloff, Majorie, ‘After Free Verse: the new non-linear poetries’, http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/perloff/free.html.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/33/stuart-drucker.shtml