Paul Stephens

reviews

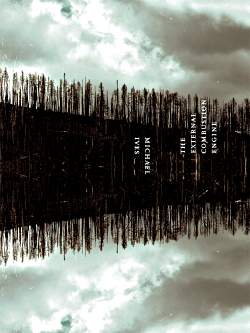

The External Combustion Engine

by Michael Ives

New York: Futurepoem Books, 2005. Paperback Poetry/Prose, 0-9716800-4-3, 136 Pages, 6×8, USD$14.00

This review is about 4 printed pages long. It is copyright © Paul Stephens and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

Infernal Combustion Engine, an example of hypallage: “a deliberately misapplied epithet, as when, in a well-rehearsed mistake, Churchill referred to the “infernal combustion engine” (Lanham 86).

2

External Combustion Engine: “An engine, such as a steam engine, in which the fuel is burned outside the engine cylinder” (American Heritage). Here, a book of prose poems which turns the lyric subject inside-out. In its avoidance of much-abused traditions of lyrical minimalism, The External Combustion Engine combusts the reader, not just the writer. At first, the “external combustion engine” seems like an example of hypallage, but being actually existent, it soon proves an important tool for transforming the lyrical ego.

paragraph 3

From her grave, Sylvia Plath rolls toward her well-thumbed thesaurus. Wandering through the landscapes of the Hudson Valley, Michael Ives responds psychomachically, reaching into a vast repertoire of language. An encyclopedic quiver of linguistic arrows makes for a demanding catachretic juggle. A dictionary is recommended. In the meantime, a lexicon, made entirely of words derived from the much-derided root Pros-, is provided. None of these words are used in Ives’ book of prose poems; this lexicon is intended as a window into issues of poetic and prosaic form which mark this book’s important contribution to contemporary literary experimentalism:

4

Prosonomasia: “A nicknaming” (OED). These poems insistently rename, overname, and unname. In their attempt to untorque the wound-up springs of the New York School/Language poetry fusion that dominates contemporary poetry, these poems can be maximalist in the extreme. Wind a spring far enough in the other direction and a different kind of prosilience (see below) results. The reviewer imagines that the most likely way a reader might misunderestimate this book is to mistake its learnedness for poicologia (overly ornate speech). The book is resolutely Grecian in its linguistic demands, but you will rarely find Michael Ives resorting to a needless polysyllabic word.

5

Prosaic: “Lacking poetic beauty, feeling or imagination.” (OED) The best disguise is always to blend in. These poems revel in rhythmic prosiness, and thrive on poikolonymy (the mingling of names or terms from different systems of nomenclature).

6

Prosilient: “Leaping forth, fig. outstanding, prominent (OED): This book is hyperbologic in all the best ways. The long poem “The Seizure” in particular seizes the reader by his epiphany, and refuses to let go. “Here is the supinity that journeys to hell, Chablis in hand, and returns late that evening to broil the striped bass” (92).

7

Prosopoeia: “personification or a figure by which an absent person is introduced as speaking” (OED). These poems are not monologic; they are extremely “writerly” in that they most often they converse with you, the absent reader.

8

Proseity: “The quality or condition of existing for itself, or of having itself for its own end” (OED). This turning inside-out is part of an incessant search for autarky — with a recognition that autarky is slippery and elusive. “The self betrays itself so predictably and with such a fine rigor, one would think that by now it had an illuminated manuscript leaf of the ‘Kick me’ sign taped to its back” (99).

9

Proselenic:”Existing before the moon” (OED) A poem like “Précis of historical consciousness” operates on a fully charged Heideggerian battery. But a book that begins with the sentence “Uh-huh, I temped once” immediately acknowledges how humble and dirty ontology can be. The ECE somehow manages to feel atavistic and ahead of its time all at once.

10

Prosimetrical: “consisting partly of Prose, partly of Meeter or Verse” — Blount, year 1656 (OED). Swaying between the grand Euphuistic style of “The Seizure” to the plain Attic style of “Gong Drops,” the engine motors nimbly, fuelled by chiastic inversions: “One person’s center is only another center’s person” (100) or “We are such dreams as stuff is made on” (110) or “The unlived examination is worth living” (110) all reinvest linguistic compression with weighty irony. At the other extreme, the maximalist extreme, “The Seizure” moves our concern from the sentence as unit to the paragraph as unit, with its paragraphs moving as long hypotactic waves through the paratactic ocean. “The threat of lyricism hangs over each and every sentence” (89), and the best way to counteract that threat is by strengthening the levees of each sentence and every paragraph. Consider, for instance, this sentence from “The Sceptic’s Anatomical Parable of Sight as an Infinite Regression”:

11

A chauvinism merely, this within and without, the vulgar distinction of a surveyor — yet, forced to conclude, let us with policy join the mob and situate it within, as the psychological epoch demands: that the matter be concluded once and for all, and that it be within, that the powers, the receiving powers, the individuating, sovereign element — to speak liberally, the sight — that in essence, all agencies of sense, of self-making, be located within, and, for the sake of brevity, and as not to importune the precious untrammeled will, perfect and absolute self, node of intention, governor, etc., we will, if only for the record, put the sight properly within the skull — with rudest carpentry house the jewel. Idiots! (13)

12

A sentence like this is unique in the world of contemporary poetry. Twenty-three commas make for a language that is at once precise and all-encompassing. Sentences like this beg to be read aloud, not just for their Proustian sonority, but because they enact the very suspicion of psychological directness which they critique. When the paragraph ends with an emphatic “Idiots,” no one and every one is simultaneously being addressed, and the poem has abandoned the hypermaximal for the hyperminimal. From poem to poem in the book, one can find similar radical formal transitions. Whereas “The Sceptic’s Parable” is Ciceronian in its syntactical demands, a poem like “On the Train North of Ossining” is left entirely without punctuation.

13

Prosiphonate: “Of a chambered shell: Having the siphonal funnel directed forward, as in the Prosiphonate, a primary group of chambered cephaloids now extinct” (OED). No doubt a prosiphonate is a beautiful and rare creature, but one would like to imagine that prosophonics were something else, a way to describe the extraordinary attention to sound and rhythm in this book. Precedents abound — James, Jarry, Valéry, Michaux, Stein, Beckett, Ashbery, Williams, even Nietzsche, all came to mind as writers whose prose likewise negates any sonic distinction between prose and verse.

14

Prosokhe¯: “Attention [particularly to the self in Stoic and Epicurean ethics]” (Hadot) “The gauche convenience of selfhood reminds one of the pump at the side of the mini-mart advertising ‘FREE AIR’” (86). That nothing comes for free, including language, is a truth universally acknowledged by those in capitalist society. From the micrological to the macrological, the External Combustion Engine pays close attention to its surroundings, musicalizing them, unbanalizing them, materializing them.

15

Prosopyle: “A small aperture by which an endodermal chamber in a sponge communicates with the exterior” (OED). Put your ear to the aperture, and you will be communicated with exodermally. You will become a prosophile in the transition from internal to external. From her grave, Sylvia Plath cries out as the age of internal combustion comes to a sputtering end. From a prosophonic perch on the Hudson somewhere north of Ossining, Michael Ives responds prosiliently.

Hadot, Pierre. What is Ancient Philosophy? trans. Michael Chase. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002.

Ives, Michael. The External Combustion Engine. New York: Futurepoem Books, 2005.

Lanham, Richard. A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms, 2nd edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

|

Paul Stephens teaches at Bard College. He recently earned a PhD in English from Columbia University. He has recent essays in Fulcrum and in Don’t Ever Get Famous: New York Writers After the New York School edited by Daniel Kane (U of Illinois/Dalkey Archive). |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/33/stephens-ives.shtml