JACKET INTERVIEW

Eleni Sikelianos

in conversation with

Jesse Morse

2007

This piece is about 12 printed pages long. It is copyright © Eleni Sikelianos and Jesse Morse and Jacket magazine 2007. This interview first appeared in Volume 1, Issue 4 of Ellipsis magazine

[You can read excerpts from

The California Poem in Jacket 23. — Ed.]

1

For two years and two summers at Naropa University I had the pleasure of studying with Eleni Sikelianos. She led me through some very difficult and extremely rewarding texts. Only since leaving Naropa have I gotten to know Eleni through her own work, and have found The California Poem, The Book of Jon, The Monster Lives of Boys & Girls and Earliest Worlds equally rewarding, in unique ways. Eleni took time to discuss The California Poem (Coffee House, 2004).

2

¶ Jesse Morse: What texts (if any) were present with you while you were writing this? Any that you have taught? Mainly I’m thinking of Alice Notley’s Descent of Alette (though that’s very different) and Anne Waldman’s Iovis, which, structurally a bit, reminds me of The California Poem.

3

Eleni Sikelianos: What intrigued and challenged me about Descent, in relationship to my own work, was the continuous narrative of it. It seemed to me that this was the first time it had been done in an interesting way in a long while (i.e., since Homer, Dante, Milton). (I hadn’t yet been charmed by The Autobiography of Red.) There were plenty of long poems written in the 20th century, but the ones I considered part of my lineage or was interested in (Iovis, Trilogy, The Maximus Poems, Paterson, the Cantos, Stanzas in Meditation, Helen in Egypt, etc. — all of which take risks with form and language to recast reality) did not operate via the old narrative plan. We could say that all that was shattered with Modernism. (Of course, another kind of narrative arises, through the use of language, form, and so forth.) Or we could say that 20th and 21st century poetry has branched most distinctively into a Sapphic trend, in the sense of the shorter lyric, rather than the Homeric.[1] Have we been so trained, so specialized, that poets no longer have the capacity, in mind or imagination, to work in a sustained narrative form? The poems mentioned above are, obviously, long poems, but they all work through an accretion of shorter poems, often juxtaposed or arranged kaleidoscopically, to make tivahe longer work.

4

The California Poem, as I’ve mentioned elsewhere, started from a dream. The initial piece, which I wrote the morning and afternoon of the dream, is probably about 15 pages long (what are now the opening and closing sections of the poem, minus the prologue). Over the next few days and months, as I kept going back, and as the poem kept flowering and exploding, what I really wanted to do was to write a sustained long poem, not a series of shorter pieces. In that goal, I totally failed. Seven years later I found myself with a poem that more closely resembles Williams’ Paterson or Anne’s Iovis in its collage-like or kaleidoscopic structure.

5

Part of what Alice’s and Homer’s and Dante’s poems have that allows narrative is characters. Characters who are not Alice (and not exactly Dante), who act and interact. There’s a kind of geometry to that – it makes a triangle in the mind. My sense of the poem, which so far has not been able to invite characters in, has a much different shape, more like telemetry. There are ricochets, and jagged trajectories, but no triangles of human interaction. I don’t know that I can convince my creating mind to operate under or from new geometrical terms.

paragraph 6

¶ JM: You mention Alice almost immediately in The California Poem:

7

thorny and antic

shapes as tall as a house sticking up out of the desert part

of California tiny flowers frozen in the tips Needles

birthed a poet named Alice and goat-weed (p. 13)

8

Needles, CA being the town – an unbearably hot and dusty desert town – in which Alice Notley was born. How has Alice influenced your work? What’s your relationship with her like?

9

ES: Alice is one of a number of living poets whose work has been important to my sense of poetry. These living poets have a different effect than do my dead heroes. They manifest in the world as bodies to show how to move one’s own “body” of work and imagination and thought through the world.

10

I think because you asked this question, I had a dream about Alice last night. She had moved up into a steep, steep canyon that could only be reached by plane. Bernadette [Mayer] (who, in the dream, knew how to fly a plane) and I were going to visit, traveling over gorgeous red crevices in the rock — light loving the angles, shade buried in the crevices — plus a kind of tender blue sky; we nosed through soft, sheepy clouds. There was Alice standing on a cliff ledge in a long yellow-peach gown, her hair tousled about her face, some kind of attendant, also in yellow, next to her. “Come with us to where the poets are,” she said, which was around the corner, where “the poets” were sitting in patio chairs, nibbling from plates of olives and blood sausage. I suppose you could say that that’s what my relationship with her is like.

11

¶ JM:

12

Hacienda Liquor Mart in the kicking dust / I’m

riding a train in the equestrian version of the dream all over your green campus [sloping up

toward SLOtown where the horses’ torsos play ball (p. 20)

13

Jesse Morse; photo by Regan Case

I was lucky enough to have grown up in California, to know that “SLO” refers to San Luis Obispo. Did you think about that at all, over the seven years of writing The California Poem? How different this might read to non-Californians? Or is that important? . . . Moreover, what does it mean to write such an overarching epic about a very specific place? Of course, California is huge. How did you settle on it?

14

ES: I wrote the poem mostly in New York, so that is generally the foil or background. One reader found the New York part of the poem to be so prevalent she jokingly suggested that it should be called The New York Poem. And then I “finished” it in Colorado — that was initially a bit jarring, to have yet another landscape to contend with while in the poem’s process. I do, or maybe I should say, I did wonder how someone in Chicago or Baton Rouge would make sense of it. Curiously, the poem is being taught in far flung parts of the U.S., sections have been translated into French by a few different translators, there’s a bit in Slovenian, it was reviewed in a Barcelona newspaper (and I was just invited to read from it in that city[2]), a young man who’s never been to California recently wrote me about it. Now isn’t that odd? My most place-specific work seems to appeal to readers in the widest range of places. But that is the truth of place — it carries every other place in it, historically, psychically, or potentially. It’s true in a very real, material way — how our commodity demands wreak havoc in other parts of the world, and in all that has been exported or imported from and to a place, in terms of peoples, fauna, flora. In California, think Spanish, English, opossum and eucalyptus: things we associate with that place that are in fact non-native. Bits of shell from other oceans wash up on shore (I think it’s John McPhee who calls the California coastline a calico, or an attic full of baubles from all around the world). The land is a deep palimpsest, with all kinds of scribblings etched into it. U.S. place names show that vividly. Then there is the psychic history of everyone who’s walked across it, tarred a road or toiled there, or even passed through. Any place is a watery map you carry in your head to every other place you go. I have layer upon layer of shifting maps in my head, each with brightly inked streets, roads, and hills, each floating above the other. Some are scenes from dusty towns in Africa, some are quarters in Paris, others still are New York or Los Angeles or Santa Barbara, and they are all related.

15

I think I would say California / the poem / settled on me. It exerted a certain pressure — through dreams and waking obsession — in the way that some poems or parts of life do until that pressure is relieved. And it did indeed feel huge — too huge to handle. The more I did, the bigger the field appeared, and I knew there was no way I could “cover” (or manipulate) everything in it. So I had to settle on scratching at this one little spot as diligently (or at least for as long) as I could.

16

The place, too, is conflated with, sometimes in conflict with, the self — how and when and why we occupy a place — especially the place/s in which we grew up. How am I who I am because of growing up in California, in Isla Vista and Goleta and Santa Barbara, California? How is how I think about that place specific only to the fact that I was a child there, and not really to the place itself? I have always been, as a poet, not only in dreams, but in syntax and language, hyper permeable to place. I see most of my books as coming from the places in which they were written.

17

What does it mean to write an overarching epic about a very specific place? I suppose I hope that a catalogue, a calling attention to, can make something happen, save a field or two, clean up the water. It’s certainly a political poem, in its cataloguing intent. It is, perhaps, elegiac. But it is also, besides an elegy and a didactic, most definitely an ode or paean (Lorine Niedecker’s paean, and “Wintergreen Ridge” both come to mind), and odes are about love!

18

¶ JM: The California Poem employs collage; postcards; photographs; lists; scientific glossary; an historic timetable you created; drawings diagramming certain hand movements (as if from a sign language manual); fascinating, often enigmatic endnotes; textual excerpts from other books; other miscellany; and, of course, your text. How did this come about? Was this an initial conscious decision, to hybridize, or did it fall into place this way? How were all the pieces gathered? Was most of the text written first?

19

ES: A feeling arises — a feeling about language, an image in my head or seen in the world, a few words might cluster together — and a poem comes about. Then, as I’m working or reworking, a feeling might arise about the necessary direction of the work. I might have questions I want to explore or answer, I might have a conscious thought “Oh, I need to include more history,” but for the most part, thus far, I’m of the Frank O’Hara school. I can’t imagine myself saying, “I want to write a hybrid book,” and proceeding from there.

20

After the poem began, I started gathering pictures, maps, postcards as imaginative aids, things to keep by my workspace that might help the poem along. They changed from time to time, and often traveled with me. (Likewise quotes on scraps of paper that I might tape up on the windowsill in front of my desk.) The writing was, besides proceeding from memory and dreams, a fairly visual process — looking at maps of California or photographs or paintings sometimes for hours. From very early in the process, I pictured the poem with “illustrations,” as resting spots for the mind — especially because the poem contains so much “information,” I wanted there to be non-verbal sites that might work like an eddy in a stream, where the mind can relax for a moment or two. The impulse to include so many images and forms in the final version was, at the same time, probably an extension of how a poem has often started to gather for me — as a challenge to include or do something I shouldn’t, to expand the edges of the poem toward what “shouldn’t” be there. Soon, as with the languaged parts of the poem, it seemed that any and every thing could be included. A postcard your fellow Naropa alum Daron Mueller sent me ended up on one page ... that was, I think, the last addition.

Plank Road

21

The first image I knew I wanted in the poem was the postcard of Highway 80 that appears on page 75. I saw it in a postcard show at the Center for Land Use Interpretation in L.A., a kind of mysterious “museum” that focuses, as its name suggests, on land use. (Right next door to the equally mysterious and much more famous Museum of Jurassic Technology.) The hundreds of postcards on display were taken by Merle Porter, the “Postcard King,” who traveled around in his van for fifty years, taking photographs for and selling postcards. (There’s a photo of the show and description of Porter at www.clui.org/clui_4_1/lotl/lotlsu99/merle.html.) I had to track down Porter’s widow for permissions, which was a wonderful experience. His profile reminded me of some old salt my grandmother (who lived in a trailer in the Mojave Desert) would have known, and of that passing landscape, and its people.

22

I knew, too, that I wanted a picture of the Cyclone, which opened at Coney Island in 1927 — a wooden-tracked rollercoaster (which has since been rehabilitated) terrifying to ride, and the inspiration for “wonderwheels heeled in sand” on page 127.[3] I asked poet / friend Brenda Coultas to take pictures of it for me (hence the photo on page 126). (Brenda had been cataloging the Lower East Side in snapshots for a year or two, and I loved the results of that project.)

23

I’d always wanted to collaborate with both Isabelle Pelissier and Nancy Davidson, two artist friends. I sent them copies of the manuscript, and they each made a packet of work based on the poem, from which I chose pieces, chose where in the book to place them, and gave them provisional titles. Sometimes small changes were made to the poem to accommodate the work. The book designer, Linda Koutsky (who also, with a few general ideas from me, designed how to lay out the “Timeline” on pages 80-81), scanned a bit of one of Nancy’s drawings, and that became the little image that shows where sections of the poem break or end. (This was the solution to the problem of how to let readers know where such a “gap” occurred.)

24

One of the pieces by Peter Cole (my long-ago boyfriend) came out of a trip he and I made to South Central Los Angeles right after the Rodney King riots to visit our friend Akilah Oliver (a poet, now living in Boulder/New York, who was then living in South Central). All the shop windows were busted out, goods lying in burnt shambles. Peter collected charred mannequins and made a sculpture. I wanted to reference the riots without being heavy-handed, so this photo of the sculpture (which Peter had since destroyed) holds that space (page 163).

25

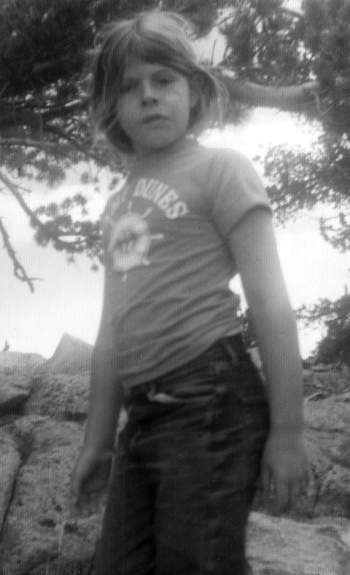

¶ JM: That is a wonderfully specific account of some of these images; your interplay with them, and how they might fit into, even shape and influence your poem. What’s the effect then? How does, for example, the picture of yourself as a child in 1972, consciously or not, influence the way we read the text?

Eleni Sikelianos at age 7

26

ES: I finally read Susan Howe’s The Midnight a month or two ago, and low and behold, it’s using a kind of bleed between the borders of the image and the borders of the text. Claudia Rankine’s recent Don’t Let Me Be Lonely uses tons of “public” images. And I was flipping through Theresa Cha’s Dictee, trying to decide whether or not to teach it this year, when I realized this book I’ve read several times is a forerunner for the trend. Anne, too, in Iovis, uses drawings, sketches. A more direct influence, more specifically for The Book of Jon and its use of images (which, I’m sure, relates to how I use images in The California Poem in some way, since I was working on them simultaneously) is Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. Of course, there are also Sebald’s novels, and, when you get right down to it, Blake’s etching-poems. Howe has been using the visuals of language on the page more radically than most for years. Olson, of course, comes to mind, as do some of the Modernist practitioners — Apollinaire’s calligrams, Huidobro’s texts — not to mention the whole history of Concrete Poetry!

27

As you know, I have a five-month old baby, and it’s been interesting to watch as she discovers text. She’s fascinated by a postcard taped to the wall near her changing table that has an excerpt from Kawabata in Japanese. Watching her has certainly made me think about the morphology of language, and how that affects/infiltrates/infects our consciousness.

28

The inclusion of non-alphabetic images obviously influences the way we read a text, whether we are asked to read a bleed or blur between the two, as in the above-mentioned texts, or whether it’s a Gustave Doré, placed in the text for illustrative effect. I think what interests me is the possibility for the poem or piece to extend into or be extended by the image in a mysterious, non-illustrative way (as done so beautifully in Billy the Kid and Sebald’s works); so that the image creates language or thought that is part of the “poem,” just as, conversely, the language of the poem creates images. When we read aloud, we sound the poem on another plane; adding images that function as part of the poem is like that — extending the plane of the poem.

29

Every poet probably hopes to expand the poem’s possibilities into ultra-language dimensions. It’s sort of what poems, especially poems that are hyper engaged with their medium, do naturally. How do you take that further? I used to have a fantasy about being able to write a dimensional poem, one with drawers that could be pulled out. That is what an interesting poem is like.

30

¶ JM: On page 38 we find “(from the snapping of twigs / we learned k’s and t’s).” Then, on page 46:

31

The tobacco hornworm eyed me from a tomato plant, its threatening

[spike veered north

Instars of my larval life running

through poison oak & toothed coyote brush, tethered to mountainsides &

[falling

for the honied romance of names

Made a dictionary arranged not alphabetically but from heaven to earth: all things

of the sky go there ➹ all things of the earth ➴

32

This writing is very exciting because I see in it a new kind of nature writing. You are making a dictionary – wentletraps, nematocysts, hymenoptera – while discussing the natural world. Your attention lies simultaneously on Earth and in its language. I find this admirable and difficult. You never let us forget we are reading, even though your most constant subject, throughout The California Poem, and even in Earliest Worlds, is nature, and what we find there... Maybe it’s the unusual language you find in the natural world, in the geology and biology textbooks, that appeals to you most? Or the idea that our language really comes from the Earth, from the snapping of twigs, and not from us?

33

ES: Early on, I loved leafing through biology, oceanography and science books. I’ve always loved that language and its richness. I don’t know if you were at Naropa the summer we read anthropologist Hugh Brody’s piece in Brick magazine from some years back, in which he talks about the structures of language. According to Brody, most hunter-gatherer languages don’t have categorical words, like fish or tree; they have specific words, like trout, salmon, perch, elm, maple, aspen, but not the broad-stroke word under which all these words fall. (From whence comes the cliché that the Inuit language has a hundred words for “snow;” in fact, it has no word for snow; instead it has many specific words for types of snow.) So, I was thinking about what that means in terms of consciousness, how we approach the world. And about Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy, and his invention of naming, ranking and classifying organisms — a system that has completely permeated our worldview. It began to occur to me that our basic bilateral symmetry might have led us to thinking about language and the world in a bilateral way. I began to wonder what kind of language these animals I’ve always loved and about which I was writing — cnidaria (which include the jellyfish), or echinoderms (starfish, urchins) — would make, given that their symmetry is radial — a kind of infinite and round possibility, when you can be sliced in any direction and still have more or less matching halves. (Some animals, too, like certain scallops and sea hares, have what you might call radial sexuality.) I’ve always felt a great (at least potential) continuity between the consciousness of nature and my own. I’m sure our early language came from things like imitating the snapping of twigs! (I think I was on a hike, when I noticed how like our occlusive consonants “k” and “t” the snapping of twigs is. Those sounds don’t actually use the voice, just the forcing of air through an occluded passageway and release.)

34

A few people have asked why I use so many difficult words in the poem, and at least one reviewer complained about it. The first times I was asked I felt guilty, like I’d done something anti-democratic (democratic in the Whitmanic sense). But it seems so odd to me, when we have a language with something like a half a million to a million words (it’s apparently quite impossible to know how many) not to bring some of its more bizarre creatures to light. I’ve often heard language described as a technology, but perhaps it could more aptly be described as a living, protean organism, not unrelated to other zoological forms.

35

¶ JM: What will you do now? The California Poem and The Book of Jon are both so important, it seems to me. A long poem, something you’ve been working on and studying for years; and a memoir about your late father, a text that personally must have been very necessary for you to write. Do you feel sated, even if only temporarily? Or do you have projects currently in flux? Or, perhaps, simply enjoying the wonderment of motherhood?

36

ES: All of the above. Soon after the books were done, I felt imaginatively and inspirationally — maybe spiritually? — wiped out. That was compounded by the feeling that it’s hard to trust language these days, when it’s being publicly used to such deceitful ends. Still, I’ve written a few scattered poems that might be worth keeping, many that will be thrown out. But language is coming back to me, even if time has run away. After these fairly large and long-lived projects, I’ve found myself wanting to write small things, or things that don’t ever have to be “finished” — sketches, notes, half-breeds, and that’s led to a series — about time, bodies, babies. These combine very bad drawings and journal notes along with essay-like material. A new mix of forms for me.

37

And maybe some day I’ll get to make a poem that moves.

Eleni Sikelianos (the great granddaughter of the Nobel-nominated Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos) was briefly a biology student in her undergraduate career, drawn to oceanography and microbiology. Although those formal studies were abandoned, the language of wild oceanaria and cellular activity has continued to inform her writing. Her two most recent books are a long poem in and around the history and sites of her home state, The California Poem (Coffee House), discussed here; and a hybridized memoir about her father, heroin, and homelessness, The Book of Jon (City Lights). Forthcoming are a selected poems in French, translated by Beatrice Trotignon, Du Soleil, de l’histoire, de la vision (Editions Grèges, 2007), a new book of poems, Body Clock (Coffee House, 2008), as well as her own translation of a book by Jacques Roubaud, Exchanges on Light (La Presse, 2007). She teaches in the Creative Writing program at the University of Denver, and lives in Boulder with her husband, the novelist Laird Hunt, and their daughter, Eva Grace. Photo: Eleni and Eva in Noah Purifoy’s Sculpture park, Joshua Tree, California (Photo by Laird Hunt).

[1] The branch that takes the poem as a vehicle for inquiry into the nature of language and reality might be an extension of the Pre-Socratic philosopher/poets.

[2] This makes me particularly happy because one line of the poem was inspired by opening a copy of The Maximus Poems in translation in a bookstore in Barcelona (close to ten years ago), and reading the first line in Spanish: “Yo, Maximus”.

[3] From www.astroland.com, Coney Island’s website: “Time Magazine quoted Charles Lindbergh as saying that a ride on the Cyclone was more thrilling than his historic first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Emilio Franco, a mute since birth, regained his voice on the Cyclone, uttering his first words ever — ‘I feel sick’!”

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/33/sikelianos-ivby-morse.shtml