JACKET INTERVIEW

Kathleen Fraser

in conversation with

Sarah Rosenthal

2007

This piece is about 20 printed pages long. It is copyright © Kathleen Fraser and Sarah Rosenthal and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

Sarah Rosenthal: Silence has been a central trope in your writing since early on. It carries a range of meanings, from erasure to grief and loss to the spaciousness of an open field. Perhaps we could trace some of the ways in which silence has come up in your work over time.

2

Kathleen Fraser: That sounds like a good way to go.

paragraph 3

SR: Silence is central to “Something (even human voices) in the foreground, a lake,” which appeared in a book of the same name in 1984, published by Kelsey Street.

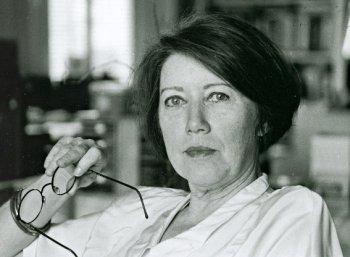

2000, jacket photo (by Arthur Bierman) for essay collection, Translating the Unspeakable, Poetry and the Innovative Necessity. (2000). University of Alabama Press

4

KF: It’s true that when I wrote that poem, I was very much in the witness position. It was maybe my third summer in Italy, after several weeks spent with a group of non-English-speaking Roman friends who had welcomed my husband and me into their lives even though we couldn’t yet speak Italian very well. They would gather every Sunday afternoon, in the country outside Rome, at the lakeside home of friends. After lunch, the men would sit at a long outdoor table talking politics, money, and sports while the women sunned themselves on a vast green lawn that stretched down to the water, exchanging information about where they’d had their hair done, remedies for children’s illnesses, pasta recipes, and their fascination with American TV soaps ... the day’s endlessly fascinating banalities. Very culturally imposed divisions there. Given my limited Italian I could barely enter into the women’s conversation, especially because it was composed of the intimate chitchat of people who’d known each other for years. The Romans talk rapidly and continuously. Silence is barely admitted. It’s not exactly that they’re nervous about it, but it’s such a habit to be talking. Their swift ease underlined my shyness since I had few words or apt phrases at my command.

|

from Something (even human voices) in the foreground, a lake, |

5

The women understood that I was a writer, and they were probably somewhat interested in that and yet threatened by it too, at least those who hadn’t pursued an education. As it turned out, our hostess was a big reader and later on had a book of my poems translated — the same book we’re talking about, in fact. Eventually she became my close friend. But in the early years spent with these friends, I’d sit there at the edge of the group, smiling but feeling painfully outside of the exchange. What kept me company was my journal. Since I couldn’t say much, I took notes on what I noticed and thought I was hearing: In every direction I looked was an incredible visual treat of food, bodies, trees, birds, and water.

6

I wrote shorthand “newsreels” starring my new Italian friends. They were always in their bikinis and continuously comparing their tans — so into their bodies and surfaces of presentation — what they call la bella figura, i.e. “looking good.” So that’s how I dealt with the particular awkwardness of a self-imposed silence — really the silence of being unlanguaged in their mother tongue. The benevolent but isolate situation thrust me into the witness position and it shaped the disjunct quality of the serial poem that I began to write out of — down to the very placing of the phrases. Being in the deficit position vis à vis words also gave me an entirely new and visually privileged subject matter.

7

SR: That writing is tonally also disjunct: I had the sense of the witness operating very close up physically yet very far away emotionally. That makes sense given the fact that the interpersonal situation was isolating, thus thrusting you into a heightened state of sensory awareness. The disjunct tone helps to enact that sharp contrast between the ways in which you could and could not connect. The last sentence in the poem reads, “It is believed that she understands partially but cannot speak except haltingly and about nothing in particular.” I read that as a fear of not being seen as having anything to contribute.

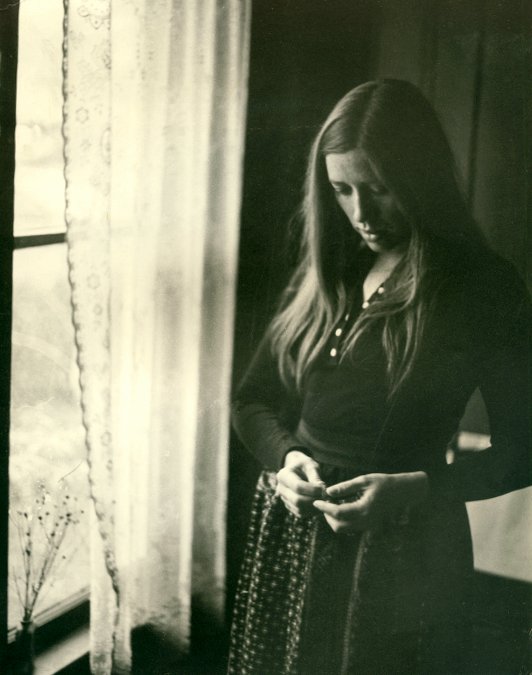

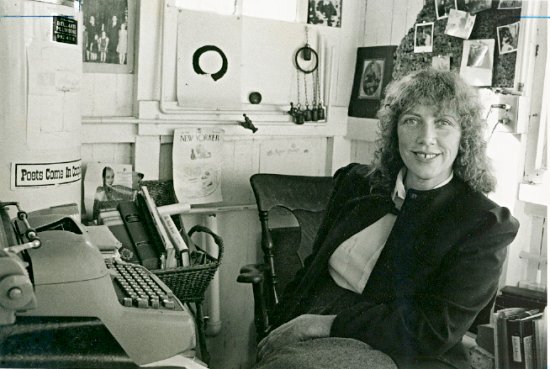

Kathleen Fraser, New York, 1964; photo taken for YMHA Poetry Center ‘Discovery Awards’, era of writing Change of Address, 1966, Kayak Books.

8

KF: That’s not how I felt at all. It was more like being in neutral — unable to move forward or backward, realizing that most of them had no idea what kind of person was sitting with them or where my mind was. I sensed that most of them needed a way of identifying me in a familiar, even simple way that they could deal with. It seemed reasonable on their part.

9

SR: There are other moments in your writing where again you articulate the experience of entering the difficulty of silence and making something out of it. In Each Next (The Figures,1980) you write, “Walking up to a new edge, I discovered in myself an old mute, but I stayed, allowing my curiosity to teethe on the silence” (p. 54). The silence is seen as dangerous or problematic but the speaker, instead of trying to escape, chooses to stay and investigate.

10

KF: I wrote that at a time when I was attempting to take big risks with my writing. I was searching for ways to chart the difficulty of human relationship, or my version of it, yet do it in a way that wasn’t mawkish and me-centered. I wanted to map it as truthfully as possible, but obliquely and ironically. For a long time in the late 70s and the 80s I was struggling to get off of that “I” place that was so prominent for those of us who came into poetry in the 60s. Being in New York City, I encountered a number of other kinds of poetries that gave me alternatives. But living with Plath, Lowell and Sexton in my ear, I had to work to uncover another poetics focused on syntax and unease. I wanted to speak from the unidentified witness perspective instead of positioning the private ego’s needs at the center of all writing.

11

I was often “speechless” in groups. I felt ashamed that my thoughts were not sufficiently coherent to share in public. What ultimately pushed me into becoming articulate was the situation of erasure — the classroom and publishing politics that I eventually saw my students facing too.

12

SR: Had you been aware of the problem of erasure before you began to teach?

13

KF: Well, sure ... it was a felt experience for many years before it was consciously named. I don’t think one becomes so passionate about a phenomenon as I did, unless you’ve felt the impact of it upon your own development and that of your peers. As a child I was often required by my parents’ vocation in the community to wear a social personality, and I felt increasing resistance to that. I was very aware of not being read correctly, or perhaps of being read too simply in a way that satisfied others’ needs. That early misreading is a kind of perceived erasure for anyone who feels it — it is almost like acquiescing to a profound lie. I suppose that as I attempted to maintain an inner sense of balance — and imbalance — the process of growing up required a kind of masking, i.e. concealing my uneasy thoughts and observations in order to avoid what I sensed as an ever-hovering critical judgment from a community of values I had not formed for myself.

14

When you are publicly contextualized in this way — that is, usefully misread within a social network — you tend to develop a strong resistance to being categorized. Within the family it was OK, we were encouraged to share anything that came to mind — and fortunately, this purposefulness was interrupted by my father’s whacky English humor. He was very keen on our memorizing silly poems and very turned on by each of us bringing our experiences to the dinner-table conversation, regardless of our age. But outside of home life, we older kids were aware of a kind of scrutiny that felt intrusive and that encouraged silence or deflection as a sort of protection or refusal to submit. In this context, silence became a bit like the blind a naturalist kneels behind to observe the behavior of birds.

15

When I went away to school, there was an immense sense of relief — getting away from all this personalized sensitivity and parental need for appropriate social behavior. In New York City, at the end of college, I was just one of hundreds of “struggling young writers” trying to educate myself and get a fix on the contemporary arts world. This included a vast potluck of poetry readings one had little taste of in school. It was an entirely different immersion that required an appetite for the new and strange — the brilliantly performative as well as the difficult, more private investigations. I did a lot of listening and reading and sorting through of the writing — and the ideas about writing — that seemed compelling to me — everything from letters between Robert Creeley and Charles Olson to Levertov’s Welsh-inflected lyrics, Duncan’s open-field song, Spicer, Neruda, and Bishop. All of it seemed immense, rich, and inconclusive.

Kathleen Fraser, Iowa City, 1969–71, while teaching at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The photo was part of a photo shoot for the jacket of the book What I Want, 1974.

16

To listen to how one wanted to write. It was the compelling thing to be doing. Coffeehouse open mikes were where one listened and often got bored. There weren’t many writing programs. You hovered at the edges of conversations among the older writers and learned who to read. There were so many tones and shapes evolving within the house of “the poem.” While I was intrigued to read the Black Mountain poets, I discovered that there was a lot of humor and celebration going on in the New York School atmosphere. I needed it and thrived — in particular on O’Hara, Schuyler, Guest, Edwin Denby, Kenward Elmslie, and the second-generation writer, Joseph Ceravolo.

17

Then Oppen came into my life in 1966 and a few years later, in California, I stumbled upon Niedecker in a “women poets anthology” called Rising Tides. These two relocated me in silence and the regardfulness for each word’s pitch and placement, the space of quiet between lines that allowed this to happen. But I would have had no room to hear that discretionary music without first knowing the wild ride of poetry in Frank O’Hara’s hybrid of high culture and camp invention or the surreal mystery of Barbara Guest’s hidden language. They were the beginning, for me, of a true freedom and linguistic exploration.

18

SR: I want to make sure I understand the connection between the evolution of your own writing and involvement in the writing community, and your wish to support the emerging writers you were later meeting as a teacher. Because you had struggled with feeling silenced, and because you had come to recognize your own need to make contact with that silence, respect it, and find ways to put it on the page, you were particularly sensitive to what you saw your students experiencing, and you wanted to help create a safe environment for them to do that exploration too.

19

KF: It was a two-part urgency, really, once I began to teach in the late 60s — first, to create a classroom environment in which private and often “inarticulate” writers could learn to trust their imperfect, partially formed thoughts aloud — because that risk was necessary in order not to be spoken for. The other strategy was to introduce nontraditional readings from many sources and to invent assignments with sufficient permission built into them so as to invite intense listening — that act of attention to what was being inadvertently refused or censored as poetic material — and to find ways of getting its barely-there quality onto the page.

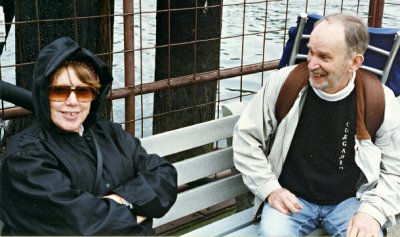

KF and Barbara Guest on the prowl for more Pro-Secco, at the marriage of Katharine Ogden and writer Leonard Michaels, 1996

20

When I first started teaching at San Francisco State I was conscious of this. The previous year, at Reed College, I’d assembled an unofficial reading group with a handful of my students to read a small selection of the erased Modernist women writers, including Gertrude Stein, Mina Loy, and Dorothy Richardson, with a feeling of adventuring into unmapped territory. I arrived at San Francisco State the next year (Fall, 1972) primed to teach the works of these mostly unknown, untaught writers. But I soon got into trouble because I noted in meetings that there were seldom any women authors being taught or included on required reading lists in English or creative writing courses. As far as the Modernists went, they were represented by Joyce and Eliot and sometimes William Carlos Williams. Virginia Woolf certainly wasn’t on the “20th Century Novel” list at San Francisco State. The evidence was adding up to a warning I couldn’t avoid.

21

SR: How were the women students in the program reacting to this state of affairs?

22

KF: Since I’d been hired to direct the Poetry Center as part of my job, women students began coming into my office to complain that they weren’t being allowed to study women authors for their “Major Authors” exams. There was a committee that traditionally decided whether a graduate student’s selection of three major authors was “appropriate.” These committees were composed only of men since there were no women teaching in our department when I was hired, except for Kay Boyle, who was retiring. The reasoning went that hardly any women writers could be considered as sufficiently “major” because not enough critical scholarly work had been done on them. But since students weren’t encouraged to read, do research, or write papers on these writers, it was a catch-22. This was the norm in universities across the country.

23

Things clearly had to change. I thought that our faculty might listen to the students, so I suggested that if they really wanted to make an impact, they would need to organize. I’d heard word of a women students’ union starting at U.C. Berkeley, so I suggested our grad students put together a group and let the faculty know in a respectful way who they wanted to study and why they thought it was important. Within about three days they’d organized the SFSU Women Writers Union. The poet Karen Brodine was one of its first leaders. Soon they were doing presentations on campus and in the community — giving papers on Modernist women writers and readings of their own work.

24

SR: You’ve been describing silence both as something one seeks out and as something that is foisted on one.

25

KF: Exactly. We worked to claim the necessary silence needed by us as writers to listen and sort through our thoughts, and to pay attention to self-censoring. But the “being silenced” took just as much work to become conscious of.

26

SR: It seems to me that both problems are political, in that the woman artist’s need for silence in order to tune into her creativity has often been thwarted. Her tuning-in capacity has been exploited to meet others’ needs rather than to create her own art.

27

KF: I agree.

|

28

SR: Your poem “Electric railway, 1922, two women” in Notes Preceding Trust (Lapis Press, 1987, pp. 25-26) addresses this need to protect one’s tuning-in capacity: “When you listen, everybody’s talking. They want you for your attention.”

29

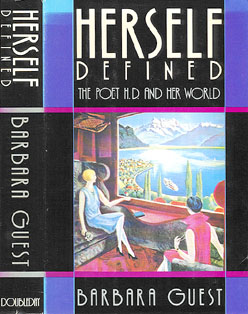

KF: That poem was suggested by the painting on the cover of the first edition of Herself Defined, Barbara Guest’s biography of H.D. Guest chose the painting because it suggested H.D. and Bryher in a secure relation to traveling through unknown territory — in a beautifully upholstered train compartment, looking out at the world passing by. I was thinking about that movement between interiority and preserving or protecting, traveling safely in known terrain, on the one hand, and on the other, curiosity toward “the new” that impels the traveler and the writer into uncharted territory. That movement between interior and exterior happened in the work and life of both H.D. and Barbara Guest.

30

As the poem “Electric Railway” developed, my thought moved from H.D. and Bryher to a woman friend of mine who was, at that moment, traveling alone in Europe, not buffered by a partner or luxurious arrangements. There’s a fine balance between protecting your inner life so that you can work — a continuous struggle for most women, who are so often “being wanted for something” — and opening up to the excitement and risk of independent experience that continues to deliver new information in unpredictable ways. I think that if you don’t attend somewhat jealously to that balance, the artist self is thrown off kilter — and usually the writing suffers.

31

SR: While “Electric railway, 1922, two women” addresses the need to protect silence in order to write, “La La at the Cirque Fernando, Paris” — published in il cuore: the heart (Wesleyan, 1997, pp. 158-168) — is about a girl breaking out of silence into speech.

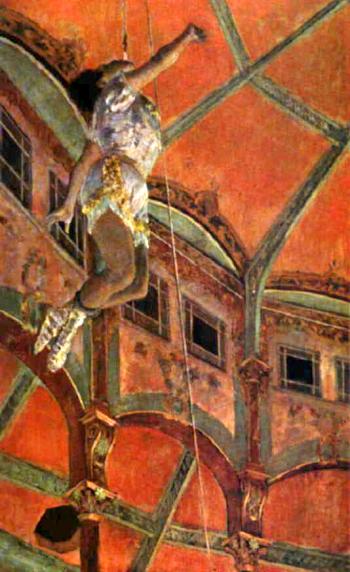

Degas: “La La at the Cirque Fernando, Paris.”

32

KF: That’s one of the first poems in which I began consciously working with the suggestion of partial or error-prone language. The poem came out of a visit to Mont St. Michel — the island promontory and its cathedral, adjacent to the west coast of France. A statue of Saint Michael is mounted atop the cathedral’s southernmost spire, raising his sword to protect France. We’d stopped there on our way down to Italy one wintry February day on a kind of pilgrimage to visit cathedrals that embodied both the Romanesque and the Gothic, and had walked through the Mont Saint Michel cathedral as well as viewing it from below and from a distance. When I arrived in Rome some days later, still with that wintry landscape inside me, I came across a postcard sent to me two years earlier, of Degas’ painting “La La at the Cirque Fernando, Paris.” I suddenly imagined a life for this young girl La La, living with her mother in the mud flats at the base of the Mont Saint Michel cathedral, spending her days collecting shellfish to sell in the nearby town market. Michael’s presence is iconic and absolutely reliable but without the human lure that an actual living man might breathe into an encounter. Then a living person wanders into the market one day and offers to put La La in his circus. Fernando is an itinerant “carny” man who sees the young body of La La as a money-maker. He is opportunistic and she has been looking for a way out of her small-town life.

33

It took me a couple months to discover this sequence, but its unfolding was one of those magical gifts. Although I began with a familiar lyric description, the syntax begins to disintegrate midway through the poem until finally blurting into bits of code.

34

In the early stages of the writing, while rereading a draft, I discovered that I’d inadvertently put a capital “D” in the word “FernanDo.” I thought that the typo looked interesting and that instead of correcting it I should intentionally look for other words in the sequence that broke naturally into their own hidden words. I very quickly found a series of multi-syllable words with other single-syllable words inside them. Without stopping to think about what these meant, I capitalized the inside words. When I assembled these “little” words they formed a revelatory, coded message.

35

SR: The last section in the poem is a coda about breaking the code, but it also reads like a code itself. Code has come up elsewhere in your poems. What draws you to it?

36

KF: One thing that comes to mind is that it’s a way of protecting oneself from being too vulnerable to an oversimplified reading. One of my earliest books, In Defiance of the Rains (Kayak, 1969), while not written in code — not “this equals that” — was definitely written slantwise, under the wire. I was getting uncomfortably close to dangerous material that I was only half-prepared to shed clear light on, so those poems were written almost as hidden messages to myself. There’s still a lot of reference to “I,” but it’s already more encoded or displaced.

37

SR: It sounds as if encountering the work of poets such as Oppen, Niedecker, Spicer, and the women Modernists helped you break away from that insistent “I” and bring more silence as well as more innovation to the page. What else helped you make that shift?

38

KF: Starting to spend part of each year in Rome began to deeply effect my work. In 1981 I spent six months in Europe on a writing fellowship, entirely away from teaching — much of that time in Italy. By the late 80s I was living in Rome regularly for the entire spring semester. I had time to take in the history around me — the architecture and the crumbling ruins and the layers of buildings pushed on top of each other through centuries. Living there opened me up and lifted me out of my personal and narrowly American situation into a much larger sense of history and community. It created a temporal and spatial shift in my work — through the very dailiness of a larger, older world flagging my attention. I began to let the visuality of history enter the compositional field and claim space.

KF, right, mid-90s, in conversation with poet Robin Blaser, Vancouver

39

In when new time folds up (Chax, 1993), the four poem sequences focus on Italian history from Etruscan times up to the continuous reconstruction and repair of present-day Rome — and visualize, sometimes playfully, elements of alphabet, notation, and erasure. To give one example, in the poem “Etruscan Pages” (pp. 7-34) I got involved in the look of Etruscan writing and alphabet and incorporated little visuals as part of the text. This graphic notation had cropped up in earlier work, but in this sequence its presence demanded more space. I’d visited several largely untraveled Etruscan ruins and was quite taken by the beautiful Etruscan alphabet carved into tombstones recovered in several museums. I wanted to presence the letters I saw there, originally scratched into tufa (volcanic rock used for burial stones) with red berry juice, as well as those letters pressed into a very thin gold tablet or “page” that now hangs in the Villa Giulia, the Etruscan museum in Rome. These are some of the only linguistic artifacts that remain to instruct us, because the Romans, who conquered the Etruscans, erased all their sources of writing by burning their wooden tablets of carved writing and melting down the metal tablets of writing to make ammunition. There had existed this life-celebrating culture, with its dancers and beautiful pottery and erotic presence vividly alive on the painted tomb walls, and the Romans just wiped it all out.

40

As a result, my interest in typography was reawakened — an interest going back to high-school days working in the composing room of the local print shop with the guys who used the old linotype machines to set the text. Scrolls of hot metal were always littering the floor. You had to hand-compose the type for headlines and lock the words and letters into a wooden frame. I loved the smell of ink and working with those craftsmen — real life, in the isolated context of public high school. That’s where I began to understand how words were put together. “Etruscan Pages” returned me to that interest. I drew some of the Etruscan letters by hand, inside sections of the poem. I wanted that hands-on feeling.

41

SR: Both the notion of erasure and a playful approach to language and the page are also manifest in “AD notebooks,” which appears in Discrete Categories Forced into Coupling (Apogee, 2004, pp. 54-68). You wrote that poem in response to the fact that both your mother and a favorite painter of yours, the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, got Alzheimer’s disease within the same period of time.

42

KF: My mother had suffered from Alzheimer’s for about five years by the time I wrote “AD notebooks.” She was, at that point, unable to recognize me. The last time she could travel to San Francisco for a visit, I showed her the artist’s book boundayr, a letterpress book that I’d collaborated on with Sam Francis (Lapis, 1988). She’d always loved art and had been intrigued by my poems early on. She turned to me and said, “Oh, wouldn’t it be wonderful to do something like this? Do you know the person who wrote these?” I said, “Mama, it was me, your daughter. See, here’s my name.” “You’re my daughter?” she said. It was alarming, but at the same time it was just part of the process, the beginning of this absence, this taking away of the person I could most count on in the world. A lot of the descriptions in “AD notebooks” are about the place where she is still cared for in Southern California.

Mid-nineties Christmas festivities at home of Margy Sloan & Larry Casalino, with son David and husband Arthur Bierman

43

There were two specific events that propelled me into that poem. One was a show at the San Francisco MOMA of late work by de Kooning, who was still living at that time. There’d been a lot of argument among critics about this exhibit: Some were saying that he didn’t know what he was doing; that his assistants were mixing the colors for him. But several of these assistants had made videos of him working on the paintings and argued that the work was de Kooning’s. It was clear to me that he still had access to the part of his brain responsible for movement and spatial distinction. It was the memory function that was shattered and confused. I saw in the work something that often happens with older artists: They begin to simplify. de Kooning was famous for the women he’d painted in the 50s — pictures filled with slashing brushwork and intensely conflicting colors. Now he’d finally reached a very clear and peaceful place on the canvas. The colors were calm — extraordinary rich whites, yellows, and pinks. In one picture, he’d painted over earlier layers but there was a little area — a small aperture — that revealed a fragment of an early work, like a piece of one of his paintings from the 50s. I was amazed to see that.

44

The other event that engendered the “AD notebooks” poem came just before I saw the show. I’d gone down to Pasadena to see my mother. The medical staff had needed to put her on a calming drug because she’d taken out her upper bridgework and had thrown it across her room. This had been replaced at great cost, and then she’d thrown it away again. She clearly didn’t feel good with something “foreign” in her mouth. This was very aggressive behavior, of course. When I saw her confused and angry face, it so reminded me of de Kooning’s enraged women. I could imagine her that way, because she sometimes had outbursts of temper when I was a child. It wasn’t present most of the time, but when she got mad, you knew you’d better pay attention.

45

“AD notebooks” is a fiction. I placed de Kooning and my mother in her health-care facility as fellow patients, passing each other and making slight contact, and him painting her. But it’s full of real, observed details such as facial expressions and eating behavior and the continuous movement and attempt to escape the building so characteristic of Alzheimer’s patients. Also, there are real descriptions of his paintings in this piece. I included quotes from some of the critics in one section.

46

SR: “AD notebooks” explores a vanishing point that, as an artist, one tries to get to — a place where the ego is quieted. The characters in the poem are approaching that vanishing point. They’re experiencing the disintegration of the self, the entry into silence. They’re leaving behind language and memory, both of which are fundamental to the construction of identity. You’ve talked about how you’d been working for years to break the grip of the “I.” Now you were confronted with two people whose physiology was doing it for them. It was a very high-stakes situation because one of the people was your mom —

47

KF: — and the other was one of my favorite painters —

48

SR: — who was still serving as inspiration even as he was in the process of disappearing. So the investigation of presence and absence takes on a whole new layer of meaning. There’s a palpable sense, in the poem, of the little fragments of language bubbling in and out of the silence. It’s almost scary how deeply you entered into the experience of your mother and de Kooning. Witnessing and creating seem to become one and the same. I wonder if writing this poem took a toll on you.

49

KF: It did really affect me. I worked on it for two years. I didn’t want to put it out there until I had it right. I did place one early version in a journal, but I never should have done that. It wasn’t ready yet, and I was always sorry afterward.

50

SR: There’s a wonderful quote by de Kooning in the poem: “...because when I’m falling, I’m doing alright...when I’m slipping, I say/ hey I’m really slipping most of the time, into that glimpse...” It’s such a liberated image. The permission to fall, the act of falling — falling into artistic vision, or into some sort of state of grace, perhaps — seems especially significant because elsewhere in your work, rising is clearly the desirable action, for example in the image of La La being raised up high in the circus tent.

51

KF: With the audience on edge, waiting for her to fall. As you get older, you realize that there’s some horrible part of human nature that wants that to happen — that anticipates a violent ripping of the fabric.

52

SR: Tell me about the section called “making more white.”

53

KF: In that section, I was trying to physically enact how de Kooning was working. I took an earlier section in the poem, “radiant inklings,” and I erased words from it. For the most part the words in “making more white” are in the same position on the page as in “radiant inklings.” I did add the phrase “THING SIFTS THROUGH.”

54

SR: This poem prepares us for all the white space in hi dde violeth i dde violet, a poem published as a chapbook by Nomados Press in 2003. That poem also deals in a very intense way with the dance of presence and absence, manifesting it aurally, visually, and thematically.

55

KF: I wrote that poem for Norma Cole, who had suffered a stroke just before I left for Italy that year. She was still in the hospital doing rehabilitation and couldn’t yet speak, and there wasn’t going to be any way to be in contact. But I wanted to communicate with her. I wrote the poem to share with her some of the experience of being in Rome over Easter — Pasqua as it’s called — and little Easter, Pasquetta, the day after Easter when everyone goes out to the country and has a picnic.

56

We were staying with our friends Wanda and Oliviero at the lake. Everything that was going on was so Roman — sweet, bourgeois, and nutty. I started the poem by simply writing through a lot of notes I’d taken, again and again trying to make a coherent poem of the foreign cinema I felt inside of. Finally I just got sick of the coherence of “the poem.” It seemed too good, too well made. It wasn’t acknowledging enough of the theft of speech, the linguistic derailment that Norma had encountered. Nor did it sufficiently address my feelings of loss, present throughout that spring, due to the death of four other friends in that same interval. In truth, I was filled with a sense of incoherence and of everything cracking apart, intensified by my awareness that Norma couldn’t talk or write words.

57

During this time some friends in Rome, visual artists, were putting up a show. They wanted me to give a reading for it, but I wanted to make something with my hands. One morning I woke up and reconfigured my poem text to the largest typeface I could find, and printed it out and then began cutting into it, not paying attention to meanings. I cut straight up through the pages vertically and then horizontally, cutting through words and letters. I made one rule for myself: to use every word and letter in the original text. Then I spread everything out on the floor of my workroom and started collaging the words, gluing them in different arrangements onto sheets of Fabriano paper. It was so absorbing. When I finished, I hung them all up on my wall and made a little show. I invited two guests: my husband, Arthur, and my scholar friend Marina Camboni, who had translated a lot of my work into Italian. Then I felt satisfied.

KF with Peter Quartermain — esteemed book designer, editor, printer, autobiographer and gentleman rabble-rouser, on the way from Vancouver to the San Juan islands to read Basil Bunting. Mid-90s.

58

Soon after that, my friend Peter Quartermain wrote that he and his wife Meredith were doing a new series of small books, and asked if I could give them something. I thought that I had nothing, but after a few days I wondered if I could reformat the wall hangings into pages. I proposed this to the Quartermains, knowing it was not what they had in mind, but they decided to do it.

59

SR: hi dde violeth i dde violet and “AD notebooks” are both visually inventive in terms of form. For me, though, the dominant feeling of “AD notebooks” is awe in the face of silence, whereas reading hi dde violeth i dde violet, my dominant sensation is joy — tremendous joy against a backdrop of grief and loss. In addition, hi dde violeth i dde violet takes the stutter, the error, the disintegration of language much further than “AD notebooks” — here the language breaks down into not just words and phrases but phonemes and letters. James McCorkle wrote something about “Etruscan Pages” that I thought applies even more acutely to hi dde violeth i dde violet: “To be in error, to mistranslate, or to invite accident becomes a means to re-present and re-iterate the possibilities of process” (“Topographies: the play of silence and space in Kathleen Fraser’s ‘Etruscan Pages,’” at www.studiocleo.com). This poem foregrounds the process of language coming into being and going away — the constant vibration between presence and absence — and invites me to reinvent and re-imagine language. I encounter new words that yield rich associations: for example, “(&ndles” looks like “(endless” — the eternity of Heaven, or of time, made to seem even more eternal because of the lack of a closing parenthesis — and “candles,” which are used in church rituals. Another invented word, “skwywr d” suggests Christ rising skyward, and “sky words” — the transcendent dimension of poetry, perhaps. The comical swirl of sounds in my mouth when I try to pronounce the word reveals an irreverence toward received language.

60

KF: I was feeling very irreverent.

61

SR: The irreverence comes through in the content, too. You’ve got woofing dogs and mozzarella —

62

KF: Yes, Wanda feeding the dogs the leftover mozzarella from the traditional Easter feast — such a casually luxurious and horribly unconscious thing to do, given the hunger in the world. But she grew up in Italy during World War Two and was used to having no food at all. So for her to have so much food that she can just throw stuff to the dogs is the ultimate gesture of freedom. There’s a great Italian word, butta (boo-tah,) that she often uses with joyous definiteness in reference to leftover food. It means “toss it.”

63

Part of the poem’s irreverence is informed by the ironic relationship that Wanda’s family has to Easter. We’ve been sharing their Easter celebrations for twenty years and it’s fascinating to watch all the funny rituals that these completely nonreligious people participate in. For example, one of the aunts sits in the middle of the living room watching a broadcast of the pope and the long Easter Mass celebrated at the Vatican, with the TV turned up fairly loud, while everyone else is preparing the Easter pranzo or hiding eggs for the children, completely ignoring the pope. My own irreverence comes into the poem in the “Christ arose” section where I layered words from the song we sang at Easter when I was a child — “Christ arose, Christ arose” — with Gertrude Stein’s “a rose is a rose is a rose” and “arroz,” the Spanish word for rice.

64

SR: The poem uses the whole page as a field. You do that in other poems, though often you make a clear distinction between what constitutes the poem and what constitutes the marginalia.

65

KF: Yes, like the sonnets in “when new time folds up” (when new time folds up, pp. 71-86).

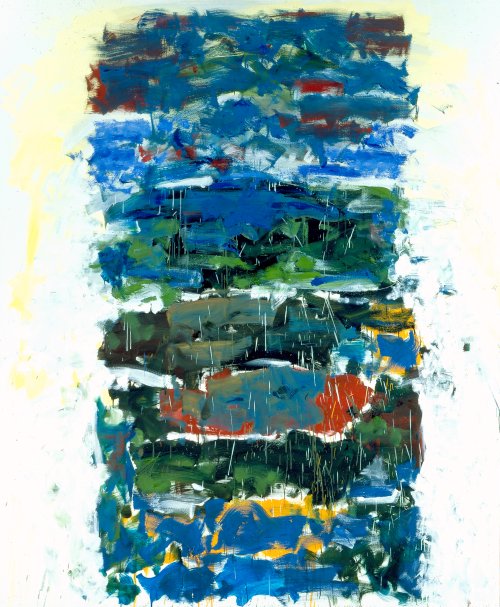

Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) “CHAMPS, 1990”, Oil on canvas 240×200 centimeters © 2007 Estate of Joan Mitchell, used with permission courtesy The Joan Mitchell Foundation and Cheim and Read Gallery, New York

66

SR: I’m also thinking of “Champs (fields) and between,” which appears in Discrete Categories Forced into Coupling (pp. 8-13) where both the “field” part and the “between” part are represented on each page, conversing with each other across white space.

67

KF: That project was written in response to the painter Joan Mitchell’s work. I was fortunate to see her “Champs” and “between” series displayed together in Paris in the 80s at Le Jeu de Paume museum. The “Champs” series stunned me with its complicated overlays of paint and motion. In contrast, the “between” series looked as if she’d taken little moments out of the larger works — just a few lines, a few colors — and framed them as a response, a zoom lens moving in on a detail, the two sides of a conversation speaking across the room to each other. I wrote notes to myself for years about trying to attempt such a movement between two sets of language.

68

SR: In hi dde violeth i dde violet, that distinction between “field” and “between” is gone. The whole poem is simultaneously “field” and “between,” center and margin. I was also struck that while each page works as a solo canvas, there’s very much a sense of continuity, of a book-length composition.

69

KF: Since I’d done them as pictures to hang on a wall, I didn’t initially compose them with any order in mind. When I decided to do the book, ordering the pages took another kind of focus. I went through a lot of versions to find what felt right, so that each page would lead in some way to the next.

70

SR: After the language has been fractured so radically and exuberantly throughout the text, the last page is surprisingly coherent and quiet.

71

KF: I meant it to work as a kind of blessing. “[L]ight opens over trees’ abundant suspend” is as close as I can probably get to whatever sense I have of a mystical presence or the event of new beginnings, new growth — a periodic possibility for hope.

72

SR: What you’re saying reminds me of something you wrote in the poem “Horologic,” which appears in your chapbook 20th Century (a+bend, 2000, unpaged): “said he wasn’t spiritual but could feel the awe, that little yes material.”

73

KF: That’s an interesting connection — orologio is the Italian word for “wristwatch.”

74

SR: “Horologic” echoes both hi dde violeth i dde violet and “when new time folds up.” It evokes the latter not only because of the presence of the concept of time in both titles but because the music and the forms of the two poems — the time-keeping devices — echo each other. Both poems have a spilling-forward sound, but “Horologic” is loaded with hard stops that bring it up short, make it stutter, show the sutures. Both poems use a highly formal container: “when new time folds up” is a series of sonnets with the last half-line sprinkled down the right-hand margin of the page, while “Horologic” comprises twelve long-line stanzas with one dangling line at the end. “Horologic” reminds me of hi dde violeth i dde violet in its rich, chewy sound: “rose geranium whistle-stop nape of neck thistle”; “lawd low Atlantis shallow.”

75

KF: “Horologic” represents an important shift in my thinking about sound. As I mentioned earlier, I began as a lyric poet but when I moved to New York I connected with the poetry of Black Mountain and the New York School and also started paying close attention to the improvised phrasing of jazz and Abstract Expressionist painting. All of these movements re-grounded my poetry in the modernist idiom. I didn’t know yet about Pound, H.D., Louis Zukofsky, or Basil Bunting, but I did know from that point forward that I wanted to escape into the American idiom. One of the means I developed to get away from the internalized values of “good” English prosody still making its unconscious demands on my ear was to go back and forth between writing poetry with line breaks and writing long sentences and paragraphs to stretch out the sound so it wouldn’t be so tightly wound and musically compressed by the old ear habits. In the late 80s and early 90s, after exploring a number of visual and sound devices in the long sequence poems published in when new time folds up, I started understanding that in fact I really loved highly compressed musical textures but I needed to find my own peculiar “condensations” — to use a Niedecker reference. Instead of pushing them away as a threat, I knew that I would work to foreground that pleasure. “Horologic” is the first work that came out of that rediscovered intention.

76

SR: hi dde violeth i dde violet seems to come out of that too. It’s such a piece of music.

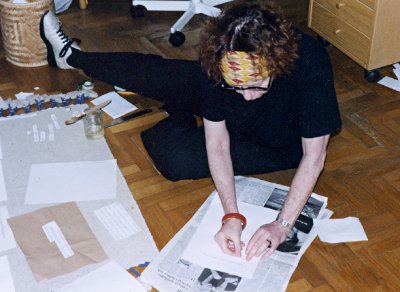

KF on floor of Rome studio, constructing wall pieces — eventually pages — for the book hi dde violeth i dde violet. [Nomados, 2003]

77

KF: Yes, it’s the purest formal experiment so far, in my work. In fact I turned to writing prose after I finished hi dde violeth because I couldn’t imagine where my poetry might go after that.

78

SR: You said in a talk at Naropa a few years ago that you’re vigilant about making sure you don’t get into habits of composition — that every few years you attempt to shake up your writing practice. That seems to be where you are now, asking where you can go next. As a writer you seem to take the word “experimental” very literally, as in, going into the laboratory, entering the unknown, mixing things around, and seeing what you find.

79

KF: I’ve come to prefer the word “investigative” to the generic and often blurred term “experimental.” One investigates the nature of language as one constructs it, and privileges the moment of work rather than any prefigured idea of what one thought one wanted the writing to look like before one started.

80

SR: I want to ask about your relationship to the Bay Area writing community. I’m assuming that for you that means the Bay Area innovative writing community?

81

KF: In the context of my own writing practice, I’ve always been attracted by the nontraditional in art and by contemporary work that finds meaning — even necessity — in testing the established, pre-approved limits of its medium. My first thrills in poetry, as a teenager, were Walt Whitman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and e.e. cummings. They were each breaking against the status quo in their particular historic moment. This was way before San Francisco or New York City.

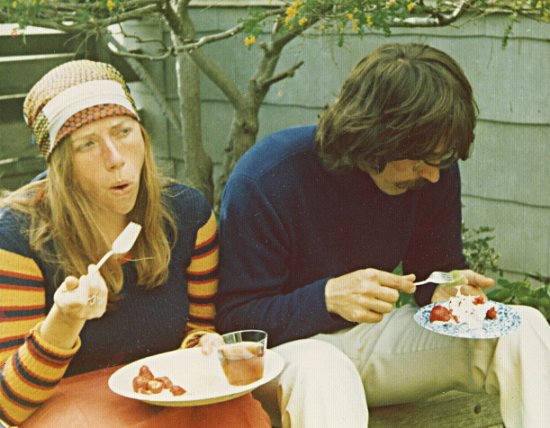

1973-1976, KF, during directorship of SF Poetry Center, at party in her backyard celebrating NEA funding for American Poetry Archives grant, shown with Gordon Craig, archive video technician.

82

SR: How has your relationship to the Bay Area writing community evolved over the time you’ve been here?

83

KF: In May of 1972, Mark Linenthal called me at Reed College (where I’d just signed a contract for two more years of teaching), and invited me to replace him as director of the Poetry Center at San Francisco State, a job that included teaching two courses for the creative writing program.

84

I arrived in the Fall of ’72 just as identity politics and student protests were hitting full tilt at university campuses nationwide. San Francisco State had recently been torn apart by a two-pronged strike asserting faculty rights to unionize and black students’ demands for relevant ethnic studies courses. President S.I. Hayakawa’s response was to fire strikers and cut back all supporting funds for the Poetry Center as punishment for its unanimous support of the strike. When I arrived, the only resource we had was a small office with three desks, a funky old couch, some bookshelves, and a few filing cabinets, with the electricity and local phone service thrown in, probably because he couldn’t separate it from the entire Humanities building in which it was housed. There was literally no budget for the Poetry Center reading program I’d been hired to “direct.” Then Donald Allen made us a gift of $1,000 for that year’s reading program, with the proviso that we lead off with a reading by Gerard Malanga. There it was in a nutshell, conflicting aesthetic and community interests entangled with economic bait.

85

Radical measures were needed and that’s precisely why and when the American Poetry Archive got invented — to pay the bills, as well as to document, via the new video technology, the complex range of American poetries being written. Because our only funding issued from a new National Endowment grant and because I had not grown up inside locally formed tastes, I saw the first year’s program in somewhat more national — and “democratic” — terms. Every invited poet was offered $50, whether they were a “star” or had just published a first chapbook. People coming into town anyway were, for the most part, happy to read. Robert Duncan read for free. Alan Ginsberg, on the other hand, demanded that his father appear as a paid poet on the program with him, and that they be put up in the Hyatt Hotel downtown for two nights — with meditation cushions, flowers, and special tea on-stage.

86

I was intent upon making space for a newly evolving consciousness around gender and ethnic awareness and a range of innovative poetries in the programming. This did not sit well with leaders of various poetry communities vying for reading space. I became an instant magnet for critique and projection.

Late ’70s, in back porch ‘study’ — counting on water heater for inspiration

87

That was one early difficulty. The second hurdle was arriving at San Francisco State as the only woman faculty member in a department of some twenty men, as a replacement for the glamorous token woman, Kay Boyle, whose famous activist politics did not include gender consciousness. By that point my feminism had become internally acute, but was not yet aligned with the ability to publicly articulate my students’ grievances to a very skeptical, all-male department of colleagues. In these first years, my learning curve was ferocious and I had little community support except for the friendship and encouragement of Mark Linenthal and his wife, Frances Jaffer, and George and Mary Oppen — all of them loyal companions who helped me to sort through the political issues and the poetics of the several closed communities that viewed me warily as an outsider.

July, 1993, Cambridge University, U.K., reading for Reality St. editions

88

Thanks to a small but fierce writing circle organized by Frances, who invited Beverly Dahlen and me to join her, my off-campus writing life began to flourish. Regular discussions and reading of our new, often improvised work changed my relationship to literature and to the local writing community. We read feminist theory together and discussed it as a deep part of our writing practice, including works by Luce Irigaray (translated by Carolyn Burke) and Julia Kristeva, as well as formative essays by Rachel Blau DuPlessis and young feminist scholars beginning to speculate on questions of erasure, power relations in publishing, and whether there was such a thing as “female language.” Susan Gevirtz , who later joined HOW(ever)’s editing group, was at work on her Dorothy Richardson study, Narrative’s Journey, which added to our growing sense of Richardson’s writing community — its filmic devices and entirely new pacing.

89

We also studied the writings of Lorine Niedecker, H.D., Mina Loy, Djuna Barnes, Dorothy Richardson, Zora Neale Hurston, and other Modernist and contemporary women writers who had not been included in our university reading lists, and were subsequently able to enlarge each other’s awareness of how things worked. Reading and reevaluating the texts we’d been left without gave us strength to reclaim them. The journal HOW(ever) emerged from these discussions. Editing HOW(ever) gave me a chance to assert some choices and to engage with the new scholars who were bringing support and curiosity to 20th century women writers and providing the missing links. Empowering ourselves replaced the feeling of needing to play by others’ rules or not playing at all.

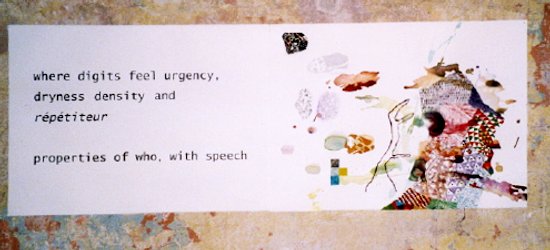

‘Where digits feel urgency’, from the April 2007 exhibit of text/image collaborative works by Fraser and NYC painter, Hermine Ford, shown at The Pratt Institute of Architecture in Rome. ( 5' long by 22" deep, mixed materials.)

90

From that period on, my relationship to the writing community was very fluid and often a great source of stimulation and nourishment to my own writing. I’ve continued to be intrigued by the invention of particular writers, and skeptical of group rule and privilege.

91

SR: What are you reading these days?

92

KF: One highly compelling nonfiction work I read recently was Mind of the Raven, by Bernd Heinrich — curiously, it was very near to my beginning the book that large black crows — or ravens — began appearing every morning on the telephone lines outside our bedroom window and on the railing of our deck. Over the last few months I’ve been reading through a small library of books and pamphlets by a new hybrid generation of young poets — David Larsen, Catherine Wagner, Jeanne Heuving, Sara M. Larsen, Martin Corless-Smith, Stephanie Young, Elise Ficarra, Cedar Sigo, Melissa Benham, Brandon Brown, Lauren Shufran, Brent Cunningham, Suzanne Stein and Brian Teare to name just a few. This work shares the quality of being highly researched and valuing an extraordinary range of imaginative and historical intervention. It has given me back my love of reading poetry and seems to embrace a huge range of what’s possible in a language unearthed from deepest necessity.

![Kathleen Fraser (right) and other evolving associate and contributing editors for the original HOW(ever) magazine [1983–1989], minus the second Contributing Editor, Carolyn Burke, who did not make it to that event. Photo courtesy of UCSD Mandeville Special Collections Library.](px/fraser/group3.jpg)

Revolving associate and contributing editors for the original HOW(ever) volumes I–V, [1983–1989], minus the second contributing editor, Carolyn Burke, who did not make it to that event. Editorial group for the original HOW(ever): Editor/Publisher, Kathleen Fraser (top row, right). Associate and Contributing Editors top row (left to right): Beverly Dahlen, Susan Gevirtz, Rachel Blau DuPlessis; bottom row, Frances Jaffer. Photo courtesy of UCSD Mandeville Special Collections Library.

|

Sarah Rosenthal is the author of Manhatten (Spuyten Duyvil, forthcoming). Her chapbooks include How I Wrote This Story (Margin to Margin, 2001), sitings (a+bend, 2000), and not-chicago (Melodeon, 1998). Her poetry and fiction have appeared in journals such as Xcp, Bird Dog, Boston Review, Bombay Gin, and Fence, and have been anthologized in Bay Poetics (Faux Press, 2005) and hinge: A BOAS Anthology (Crack Press, 2002). She has taught creative writing at San Francisco State University and Santa Clara University. She is editing a collection of interviews with Bay Area avant-garde writers. She is a recipient of the Leo Litwak Award for Fiction. |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/33/fraser-ivby-rosenthal.shtml