Cliff Fell

reviews

Eliot Weinberger, What happened here (second edition) and Muhammad, both published by Verso, 2006.

This review is about 8 printed pages long.

paragraph 1

Given the horrors and the nightmarish worlds of its subject matter – the Iraq War and the maladministration of what Weinberger likes to call the ‘Bush Team’ – the title alone to What Happened Here immediately demonstrates the wit and anger burning at the heart of this collection of essays and prose poems. In the great ‘duh’ inherent in his pun on the demotic, Weinberger shows that he will take any opportunity for a quick dig at the expense of George W. Bush’s intelligence quotient. And why not? Bush is the living face of the nightmare. The jokerman of the White House with his cheekyboy purse-lipped grin deserves all he gets.

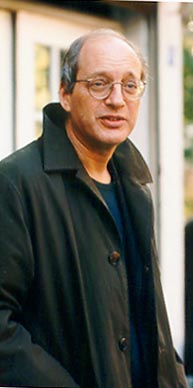

Eliot Weinberger, New York City, 1999,

photo John Tranter

2

And what he and his team get from Weinberger is much more than a subtle poke in the ribs. What Happened Here is an abundantly researched, lucid and devastating testimony of what it has been like to be living in the USA, and the world, under the Bush regime. So Weinberger’s pun is simply a preliminary circling of his project’s more serious, stated intention – to give the world an alternative view of what has happened in the USA and to signal that a voice of reason and compassion still exists in that sadly destructive country.

3

Weinberger’s subtitle, ‘Bush Chronicles,’ also has a dual purpose, suggesting two significant readings and references that underlie Weinberger’s structure and tone. The word ‘Chronicles’ brings to mind those monastic beacons of the western Christian tradition that kept a few small flames of literature and the erudition burning in the Dark Ages, preserving at least some of the cultural inheritance of the classical tradition. It is worth noting here that within the same period, in the Near and Middle East, another and arguably greater and more significant body of classical thought, including all that we have of Aristotle, was in the process of being translated into Arabic, as the tide of Islam swept into the vacuum left by the disintegration of the Byzantine empire. Later, it would, of course, be transmitted from the Arabic to the western world – via the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad and, more particularly, the libraries of the Almoravid and Nasrid sultanates of al-Moghreb and al-Andalus, during the years in which the great cities of the Iberian peninsula, particularly Toledo, were falling to the conquistadores and crusaders of the so-called Christian ‘reconquest.’

4

The notion that Islam was a principle source and translator of what the western world considers its cultural property – the Aristotelian tradition that developed into the Age of Reason and all the subsequent and ongoing ‘gifts’ to civilisation delivered, or enforced, by Western imperialism – is a little known and even less celebrated fact that Weinberger is mindful of throughout What Happened Here.

5

Nonetheless, it was the early Christian chronicles of the barbarian age that first sprang to mind on reading these Bush chronicles, particularly Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks, a seemingly lone voice engaged in bearing witness to its times and telling its perception of their truth. This is a role that Weinberger has taken upon himself in the new dark ages heralded by the selection of Bush to the US presidency in 2000. (Selection, as opposed to election, is another of Weinberger’s terms, a significant differentiation that exemplifies his attention to language throughout this book – both his own, of course, but more particularly that of the White House administration and the Republican party.)

6

Of course, in reality, Weinberger is far from a lone voice. Many in both the US and the West, let alone the Middle East, have been engaged in articulating resistance to Bush – Weinberger expressly acknowledges his debt to the work of poet Geoffrey Gardner’s Anarkiss Newswire – but it is Weinberger above all who has had the nous and reputation – not to mention the clarity, wit and sylistic scope and depth – to give voice to an American dialectic aimed at exposing the malaise and moral vacuum inherent in the Bush administration.

7

What Happened Here opens with Weinberger’s invocation of Baghdad in the golden years of the Abbasid caliphate, written at the time of the first Gulf War. It moves quickly to an essay written in January, 2001. This offers disturbing insight into the Bush Team and a very precise exposition of the Florida, 2000 election and the complicated manipulation of the State and Federal Supreme Courts that gave rise to the coup d’etat, as Weinberger characterises the stealing of the election that brought Bush to power. The only other pre-9/11 piece is a transcript of a Bush speech in which the new President jokes about the limitations of his vocabulary. This provides a brief and blackly comic interlude. (‘Bush the Poet’ offers another, later in the book.) With hindsight, it also serves as a reminder that the height of political commentary and analysis in the overlong honeymoon months prior to 9/11, consisted of ridiculing Bush’s various verbal blunders, mostly committed during the election campaign.

8

Of all that has been written of 9/11 and that fateful turning point of the presidency, Weinberger’s five epistles from New York – from ‘The Day After’ to ‘Sixreen Months After’ – will stand as one of the English speaking world’s most lyrical and intelligent response to those appalling events. Rooted in personal narrative, it’s absorbing to follow the widening of Weinberger’s focus during those months and the development of his thought, shaped as much by the people he’s meeting or watching TV with, as by the information he is coming across.

9

The first of these essays is an extraordinary act of reason and imagination. It exposes the hype and hysteria of the corporate media’s reporting from Manhattan, nails Rumsfeld in a terrifyingly sinister portrait and, in a few sharp sentences, accurately predicts the course of events over the next two years. Sixteen months later, the last of this sequence finds Weinberger on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, ruminating on the White House’s use of disinformation and on the earlier operations of the Cheney-Rumsfeld-Wolfowitz ‘sleeper cell,’ as he so pertinently calls it, particularly their subversive planning during the Clinton years. A few months earlier, in the essay, ‘New York: One Year After,’ Weinberger first employs the subtle and frequently haunting anaphora that characterise the prose poems that close the book – in this case his use of the phrase, ‘We’ve been driven crazy because . . .’ to identify the White House team’s manipulation of the American psyche during the year following 9/11.

10

While many of us will have come across parts of this collection, particuarly on the internet, it is salutary to read it as a sequence and to experience the symphonic structure and stylistic development of the book. Through the musings of an email interview and a statement for the Project of the West conference in Berlin, Weinberger circles back to his favoured form, the prose poem, for the final four sections, building up through ‘A Few Facts and Questions’ and ‘Republicans’ to the powerful indictment of the final movement, ‘What I Heard About Iraq’ and its coda, ‘What I Heard About Iraq in 2005.’

11

In assembling these searing litanies of fact and evidence, Weinberger acknowledges the influence of Charles Reznikoff’s booklength poems Testimony and Holocaust, particularly Reznikoff’s methodology in giving poetic form and voice to volumes of stenograph recorded courtroom testimony. Of course, more significantly, these poems represent Reznikoff’s logical extension of Objectivism – that term dreamt up by Louis Zukofsky at the insistence of Harriet Monroe – and remain to this day among the most comprehensive found poems in the western canon.

12

Paradoxically, back in the 70s when they were published, the principal criticism Reznikoff received was that their lack of literary artifice and reliance on found material simply did not amount to the making of real poetry. It’s a mark of how far we’ve come since then that the (prose) poems in this collection have garnered no such petty reactionism.

13

I add those parentheses to ‘prose’ with a sense of deliberation – because any discussion of What Happened Here would be incomplete without consideration of the prose poem. Those familiar with Weinberger’s work will know that, alongside the essay, the prose poem has long been his métier – a craft he has been developing since his early translations from Paz’s Aguila o Sol, particularly ‘The poet’s works’ and ‘Toward the poem,’ both of which were, to some extent, intended by Paz as essays on the prose poem’s relationship to metrical, measured poetry. What is fascinating in What Happened Here is how much further Weinberger has shifted the prose poem from its 19th century roots. In scope and subject matter we’ve come a long way from Baudelaire’s stranger contemplating the ever-moving clouds. Whether consciously or not, Weinberger has fashioned a poetic for the 21st century. As such, he follows Pound in making poetry new, once again.

14

But there are other, perhaps more important considerations than that. Weinberger has almost single-handedly revitalised the political poem as a force in the English language. Within the cadences of the prose poem he has forged an idiom that is free of hackneyed, broadside cliché and elevates the political poem simply to poem. I say almost single-handedly – among others, Robert Hass’ great poem ‘Rusia en 1931’ prefigures the voice Weinberger adopts. But in forging this style and making it his, Weinberger has found a new form for Reznikoff’s delivery of ‘the facts instead of a conclusion of fact’ – which is not to detract in any way from the achievements of Testimony and Holocaust as lined poetry. He also departs from Reznikoff in introducing the mesmeric, euphonic quality of the anaphora. And in this: the introduction – God forbid! – of the first person pronoun, singular.

15

Throughout this review I’ve differentiated between essay and prose poem, generally following Weinberger’s lead. On the whole, he seems keen to retain the difference. But at times you get the feeling that Weinberger is himself a little uncertain about where the essay crosses into the prose poem, or the ‘documentary prose poem’ as the publisher’s blurb puts it. Or that, more likely, there is on Weinberger’s part an intentional blurring of the terms. And that’s the point – who knows, or really cares these days where the prose poem ends and the essay begins? Weinberger has shifted the paradigm and it’s new and, in this book, utterly compelling.

16

If the border between essay and prose poem does still exist, it’s one that many more will slip across in the coming years, largely unnoticed for the most part. It brings to mind another influence that is also at work here – Borges’ seamless blending of fiction and nonfiction into the one narrative voice. In tone and sensibility, Borges’ playful gravitas is constantly evoked as Weinberger leads us through the fantastical, labyrinthine and nightmarish realities of the Bush world and the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

17

There’s one other thing about Weinberger’s hop and skip between prose poet and essayist, the traditonally identifiable title he is more commonly labelled under. He has in the past been notably reticent about ever calling himself a poet. Elsewhere he has spoken of his dissatisfaction with his early efforts at writing poems. Of course, as a translator of Paz, he was setting himself exceptionally high standards, but presumably we are to assume that he was referring to his efforts at the poetry of meter or measure. Whether or not he has been intentionally preparing the ground for the final and unreserved acknowledgement of the prose poem as poem, the term poet is being applied to him as much these days as essayist.

18

More to the point in the digital age, it may be that, however well the Internet serves poetry of the measured line – which it undoubtedly does – the prose poem, with its neat blocks of neverending line, will become the favoured form.

19

The Internet is also the focus of the secondary reading of What Happened Here implicit in Weinberger’s subtitle – the other aspect of its dual purpose. Many will have already come across parts of this collection online, where a number of the pieces became available almost as soon as they were published in journals or small press editions. The subtitle acknowledges that there has been a bush telegraph at work in the circulation of these essays, particularly in terms of their availability within the USA. To all intents and purposes, or, perhaps more precisely, to Weinberger’s intents and purposes, the pieces in this collection, have had a sort of samizdat underground existence, passing if not by word of mouth then by the spreading word of the fibre optic and airport connections of the new technology.

20

It’s not so much a question of censorship or suppression in the style of the Cold War eastern block that’s at issue here, but the huge gulf between the corporate public media and the independent publishing movement in the US and the West. The reality is that in any democracy, self-regulating editorial policy can behave as a surrogate for state or statutory censorship.

21

There is, though, another side to that coin, one that Weinberger has no doubt long since perceived. The corporate media belong to the culture of junk consumerism. The old adage that today’s news is tomorrow’s fish and chips wrapping is as true now, if a little more figurative, as it was in the past, and it applies as much to the New York Times as to the News of the World. If Weinberger had published any of these pieces in the serious dailies – and some of them, particuarly the earlier essays, would surely have found a home in the opinion columns – they would have been devalued and lost currency within days. Better by far to let them filter out through the internet, where, as he says, ‘it is a happy way to publish: readers vote with their forward buttons.’

¶

22

If What Happened Here is Weinberger’s epistle to the world, Muhammad is his epistle to the Americans. It’s a treasure that goes some way toward soothing the fevered horrors of ‘What I Heard About Iraq.’ Which is, essentially, how and why it came to be written: ‘With the invasion of Iraq, my antidote to the daily newspaper was books on Islamic philosophy and traditional sources on the life of Muhammad,’ Weinberger writes in an afterword.

23

The Reznikoff method is apparent again, though this time it is legend as well as fact that we are presented with. Beginning with God’s creation of the Light of Muhammad, created before even, ‘the heavens or the earth or the empyrean or the throne or the table of decrees or the pen divine or paradise or hell,’ Muhammad takes us through the Prophet’s birth, his childhood, his many – and sometimes complicated – marriages, as well as a number of the legends and miracles associated with him. That ‘pen divine’ seems relevant here, not only as a metaphor for Muhammad’s traditional role as receiver of God’s word, (initially preserved as verses by professional remembrancers within Muhammad’s close circle) but also for the transformative power the poet applies to the found poem, which is, of course, exactly what this recitative – to use another of Reznikoff’s terms – is revealed to be, and one of its boldest and most beautiful of recent examples.

24

Which raises an interesting side point: whether the Quran itself should stand ahead of Reznikoff’s Testimony and Holocaust as the first and most comprehensive of found poems. It’s a question that very few in the West, including Weinberger I suspect, are either qualified or would be prepared to pass judgement on, though were it to be explored further I dare say Salman Rushdie might have a few words to say on the matter...

25

The legends and stories presented in Muhammad are, in fact, partly derived from the Quran, as well as the Hadith, The History of Prophets and Kings (Tarikh al-rusul wal-muluk) by Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, a late 9th and early 10th century Baghdad historian, and the second volume of The Life of Hearts (Hiyat al-Qulub) by Muhammad Baqir ibn Muhammad al-Taqi al-Majlisi, a 17th century Persian cleric. But the synthesis Weinberger makes of this is toward the lyric rather than biography – he avoids any conventional trappings of historical contextualisation.

26

The result is a small, but dense book of shimmering understated narrative, a language that radiates delight and wonder, that is rooted in folk-tale and all the other stuff of magical reality – with angels protecting fruit trees, lizards that speak, talking camels and dishes of food that descend from the sky like something out of a happy day in a Harry Potter film. It’s all so much in contrast to the hell that Bush has visited upon Iraq that one can hardly miss the point, even though it might require a glance at the book reviewed above for it to become fully apparent.

27

For, as in What Happened Here, Weinberger has a clearly thought out agenda in Muhammad – stated as an intention to ‘give a small sense of the awe surrounding this historical and sacred figure, at a time of the demonization of the Muslim world in much of the media.’ But perhaps there’s more to it than that – which is why this book reads as an epistle to the Americans, even though many enlightened liberals in the rest of the Western world may recognise and give thought to how much personal and collective ignorance about the Prophet’s life a reading of Muhammad exposes. Because, for all its warmth and quiet reverence, this is a portrait of the Prophet that should, if it were ever to receive the exposure it deserves, prove of compelling and unexpected attraction to mainstream America, appealing to many of the current national obsessions and stereotypes of the consumer-driven American Dream.

28

It’s all in the smallest of details, of course. Weinberger gives us a Muhammad who likes to spend more of his money on perfumes than food; whose natural waste passes from him and is immediately concealed by the earth; who can make the hair grow again on the head of bald men; who can (with the help of a divine dish prepared by the Houris of Paradise and delivered by the Angel Jibril) sleep with all of his numerous wives on a single night. Need I go on? Somewhere, I can already hear the commercial break jingles beginning to ring… Add to that Muhammad’s wish to never quit milking goats by hand, or the well known fact that he was the One of Ones who talked with angels, or that he also once said that ‘filling the stomach with pus is better than filling the brain with poetry,’ and you’ll see that Weinberger has got the desires and prejudices of most of the American populace covered.

29

And there’s more: with his lean, dark, statuesque appearance, Muhammad is (apart from the full beard with its seventeen white hairs that gleam like the sun) more than a passing lookalike for Superman, and would, with his exemplary miraculous powers, undoubtedly prove a match for Kel-al of Metropolis any day. Perhaps that’s the point concealed in this text – that if Americans were to give serious study and consideration to a figure – or religion – all too easily demonized as an aspect of Osama bin Laden, they might well find many of their own dreams and aspirations staring back at them.

30

Muhammad concludes with a description of the Prophet’s legendary Night Journey from Mecca to the heavens, through Jerusalem and Bayt al-Mamur and the pits of Hell, particular in its horrific treatment of women. The sub-text is unstated, but clear. Muhammad is chastened, but rises from there to the seventh heaven, where the angel leaves him at a river of light, with much further still to go on his journey to God.

31

Despite those nightmarish moments in Hell, all the more appalling for their brevity, Muhammad is a jewel of a book. It is respectful and open-minded, radiant in its language and offers a compendium of information hard to find elsewhere – a book that is well worthy of a place on the bedside table . . . beside the Bible perhaps, for those who might like a flutter each way on Pascal’s Wager.