See note [1]

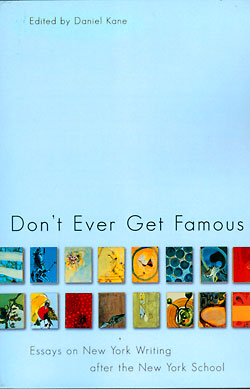

This essay is reprinted with thanks from an anthology entitled Don’t Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School, edited by Daniel Kane and published in December 2006 by Dalkey Archive Press.

If post-war American poetry is mapped onto localities, then John Wieners was a vagabond of style. From 1955 through the 1970s, he moved between the New York School, Black Mountain and San Francisco, before returning to Boston, city of his birth. From there, his writing expresses a longing for California and New York, havens of glamour and celebrity, tolerance and artistic company. Moving back to Boston signalled the absolute defeat of his ambitions:

I feel like a jaded movie star

who missed the big-time

and ended up mopping floors. (Wieners, Selected 239)

His poetry from the early 1960s, before he rejoined Charles Olson at the State University of New York in Buffalo, was infused with a sense of displacement from geographical centres and from his cosmopolitan friends. Later, Boston became his beloved; until his death in 2002, Wieners’ poetry archived the changing nature and landscape of the city. But the nostalgia which characterises his poems for friends, poets, former lovers and the “gay world” in the 1960s and 70s also extended to place. He remembered his “private residence on/ West 8th” as a “shrine of devotion to Manhattan/ Gotham shows mad weirdos and high-jinx”; but “Nothing like it is now on Beacon Hill” (“Biding in the Gloom”, Selected 274). Put simply, Boston had “nothing to match New York’s/ excitement” (“Home-Duty”, Selected 247).

John Wieners

Wieners was certainly drawn to these cities at crucial moments in his literary maturation, and he was gracious and self-deprecating in admitting the many poetic influences he found there. Among them are Le Roi Jones and Diane Di Prima, who gave space to multiple revisions of his work in Floating Bear; Di Prima also encouraged his participation in the Poets’ Theatre, where his plays Still Life and Asphodel in Hell’s Despite were staged. Allen Ginsberg may have influenced Wieners’ graphic depictions of his sexual life, but his careful, mannerist prosody is distinct from Ginsberg’s rhapsodic, spontaneously overflowing lines. Wieners’ receptivity to drugs as a means of expanding consciousness and his affection for Eastern wisdoms could be associated with the poets of the San Francisco Renaissance; a participant in Jack Spicer’s Magic Workshop, Wieners also believed in the occult powers of poetry and frequently used imagery from the tarot. But equally it could be argued that his itinerary through the major poetic locales of post-war America did not produce a related cosmopolitanism of style. His poetry retained its own distinctive character, and proved surprisingly resistant even to the influence of two very different mentors: Frank O’Hara and Charles Olson. Wieners’ poems, correspondence and unpublished prose reveal the affection and admiration he had for both men, as well as their impact on his emerging sense of himself and his vocation. He associated them with an intellectual, artistic and social liberty that would rescue him from the conservativism of Boston. All the same, it is difficult to assign Wieners a place in either the New York School or the Black Mountain or projectivist aesthetic. His similarities to and differences from O’Hara and Olson become especially apparent if we focus on three themes: the personal nature of his poetry, his veneration of celebrity, and his treatment of the past and present. These focuses will show how Wieners’ poetry relished the immediate – both the poetic record of a transcendent present, and the idiosyncratic style not mediated by other writers. It will also allow us to establish the literary influences, and resolute independence, of one of the second generation New York School’s most loved poets, who has until now received almost no critical attention.

Wieners was a fundamentally personal poet, revealing in verse the most intimate, tender or appalling preoccupations of his insatiate heart. Perhaps this makes an association with O’Hara more instinctive than with Olson. Wieners had first encountered Charles Olson on “the night of hurricane Hazel” in 1954, when he passed the Charles Street Meeting House in Boston where Olson was reading. He got hold of a copy of the Black Mountain Review and afterwards wrote eagerly to the College Registrar,

My age is twenty-one and I feel, in terms of my own development as a writer, that one to two years at Black Mountain College, “hammering form out of content” is the most worthwhile thing I could do. I am eager to study under Mr. Charles Olson, having read his poetry in Origin, Four Winds, and the Black Mountain Review, VI, No. 1, and also having heard him read his poems at the Charles Street Meeting House in Boston last year. His essay, “Projective Verse” has been the most important work I have read on the writing of poetry in 1955.[2]

Olson invited Wieners to attend the college and offered him a loan covering tuition, room and board,[3] allowing Wieners to escape Boston at last. When Black Mountain closed, he would begin the process of separating himself from Olson by moving first to San Francisco in 1957 and then to New York. Although his poetry (in particular Behind the State Capitol) is sometimes read as an enactment of Olson’s projectivist theories, from the time he arrived in San Francisco and embraced the drug-impacted, alternative lifestyle of North Beach, Wieners avowed an autodidactic style. He declared that “I must unlearn what has been taught me”, rejecting not only Olson’s prosodic technique, but also Olson’s epistemology and his revision of intellectual and poetic history. Nonetheless, Olson’s description of himself as an “archaeologist of morning” remained influential to Wieners’ conception of the work of poetry. As Olson elaborated, “I find it awkward to call myself a poet or a writer. If there are no walls there are no names. This is the morning, after the dispersion, and the work of morning is methodology: how to use oneself, and on what” (Collected Prose 206). Wieners’ mystical understanding of the poetic vocation had this in common with Olson: barriers between being a “writer” and any other occupation must be pulled down, so that the self and his own experiences of the instant could be used, to break through to truth.

Black Mountain had served as Wieners’ initiation into the sacred and magical mysteries of poetry. There, “Big Charles put his hand on me, and ordained me a priest” (Wieners, “Youth”, Selected 229). But Olson had a problematic relationship with Wieners’ natural idiom: personal poetry (or, as Wieners would describe it, not confessional poetry but “obsessional”). Olson had told his students to become “personal revolutionaries”. The power of that instruction is especially evident in Wieners’ two early works, The Hotel Wentley Poems and The Journal of John Wieners is to be called 707 Scott Street for Billie Holiday 1959 (published in 1996). These books take the observations of his “5 senses” as his material (Journal 13-14). They declare a commitment to writing as derangement of the self and the processes in which that self encounters the present. Certainly in Wieners’ poetry that present is mottled by the shadows of the past. But it is his past, not America or humanity’s – his absent lovers, his melodrama. His poetry is produced out of isolation and private suffering, however much he depends on other writers for artistic, physical, and emotional sustenance. Wieners is a personal poet, but as he wrote to his fellow alumnus Ed Dorn, his were “not revolutionary sentiments; we leave each other alone/ thinking we can take care of ourselves”. Despite such claims to independence, his poetry also acknowledges that from the beginning of his drug addiction in San Francisco, through his stoned and heartbroken days in New York, to his decades of mental illness, it was poetry and poets—and, to some extent, the celebrities of his imagination. Michael Davidson argues the “unfashionable case” that “insularity is often necessary for the creation and survival of culture poetry” (Davidson xii). Wieners frequently confessed that the insular poetic community allowed not only his poetry, but himself, physically, to survive. In his poetry the literary and the personal, the aesthetic and the biographical, implicate each other fundamentally.

Frank O’Hara was one of the poets who took care of Wieners. Meeting O’Hara in Cambridge at the Poet’s Theatre in 1956, after he returned from Black Mountain, Wieners was tantalised by this proxy for the excitements of the big city. O’Hara was acting in John Ashbery’s play The Compromise, or Queen of the Caribou, and Wieners was stage manager. He memorialised a night with O’Hara and Jack Spicer in his “dreadful room infested with roaches”: “while I read my poetry in the humid summer evening of Beacon Hill, the both of them wept through the incipient rain and electric-charged air” (Cultural Affairs 80). That O’Hara did admire Wieners’ poetry is attested by his poem “To John Wieners’:

And one day weeks later the muffler grey and old

for one so young unwraps its sheaf of poems

heard already among the sets under the worklight

a voice is heard though everyone was mumbling

now so silent that the dark is all blown up (Collected 247)

O’Hara embodied something of the glamour which Wieners admired in the movie stars. Wieners was immediately drawn to O’Hara’s irreverent humor, “his sophistication, his knowledgeability of the New York art world” (Selected 297). Wieners’ poem “After Reading Second Avenue” is full of admiration for O’Hara’s “cosmopolitan incline” and “metropolitan tableaux”. O’Hara was his first taste of New York life, “lox, & other delicacies”, parties, satire and celebrity.

But where O’Hara had seemingly unlimited access to New York’s mysteries, Wieners described himself as feeling excluded and unpresentable in his own brief periods of residence in the city. After treatment for drug addiction and mental illness, he moved to New York in 1961 with help from Allen Ginsberg’s Poetry Foundation, and found work at the Eighth Street Bookshop. O’Hara and other members of the poetry community helped him settle in – O’Hara arranged for John Bernard Myers to include the poem “With Mr. J R Morton” in his magazine Semi-Colon, one of Wieners’ first important publications. But other poems from this period, like “Tuesday 7:00 PM”, are pæans to New York’s bounded and exclusive spaces seen from outside. Gates are guarded by the “mastiff bitch”, gardens are walled, windows curtained with “the hopes/ of the poor”. The title of another poem from “Autumn in New York” laments that only in “Dream” and in poetry will Wieners dance “on the roof of the Waldorf Astoria” with a glamorous woman dressed in cocoa-coloured silk and pearls. Consequently, while O’Hara’s poems explore the real freedoms offered by the city alongside the promises of the spectacle, Wieners’ poems seem increasingly to split the real from the spectacular, with one as the domain of pain, slang and particularity, and the other as the haunt of unadulterated happiness, formal language and hazy abstractions.

The difficulty of negotiating between these two divided realms is articulated in his poems adulating the stars. Celebrities also dwell in restricted spaces, are the “dream” of the culture industry; but the tabloids and gossip columns raid their privacy, expose their limited interiority to public view. The stars are at once apotheosised and perfect, and vulnerable to exploitation and humiliation. Wieners uses a range of enthusiastic adjectives to describe their emotional lives: they are thrilled, elated, honoured by their experience of admiration; they are joyous, magnificent, ravishing, passing on their ecstasies to their admirers. In Wieners’ poems, the lives and fortunes of Joan Crawford, Jane Fonda, Bette Davis or Barbara Hutton become mystical dramas of impossible perfection. Barbara Hutton is taken by train in a white silk crib to the White House with 500 devotees hanging on; she is not just materially privileged, but valued and loved by everyone around her (Behind the State Capitol 144). The stars return this devotion to the common people; they are joyous, effusive, grateful, they protect their fans. Marlene Dietrich moves “majestically down the avenue to guard over/ the war torn refugees, waifs who lined the house” (“Youth”, Selected 229); Barbara Stanwyck is “a watchful, ever-abundant woman, with the greatest sympathy for the sensitive, easily-oppressed individuals in our society”, and Wieners – a Marian Catholic, who believed he had himself been visited by the Virgin – imagines himself ‘surrounded by her devotion” (Superficial Estimation 20-2).

Despite such florid raptures, Wieners recognizes the stars (and especially their perfection) as commodified spectacles. They live in the liminal space between total happiness, admiration, beauty and projected desire, and the tawdry realities of capitalist exploitation. In an unpublished modified sonnet “To Ross”, it is O’Hara’s tipsy heroine Lana Turner who speaks:

I travelled fast, in a gold turban for the Eastman Jefferson Airplane

to win not one Academy Award, but four snowy sedans gratis

past Le Place Vendôme, at Julien’s or Chicken-in-the-Basket

where 3,000 glass imitations of my teats, suckled and craned

Times Square, at Maxie’s, Sardi’s, Barney’s, Andy’s sneak

preview, before the Grand Hotel, Le Belvedere Gardens, Albany, Albermarle,

and the big shots, the racketeers, chanteuses, off-Broadware cafe suites

kept pace with my income, swept me off my feet, 300,000 dollars

a year in taxes alone. I had to make films; Cass Timberlane, Johnny Eager,

The Postman Always Rings Twice for Bugsy, Marion, Luana

were in debt, needed some clothes, money to pay the rent, the legs” stockings, beggar

their gems tonight, as they draw their gats to

put out this fury that tallies their totals meagre.[4]

Lana Turner, the tragic starlet who was embroiled in the murder of her lover Johnny Stompanato by her fourteen-year-old daughter, is brought to the collapse ironized by O’Hara by money and exploitation. Like the hero in O’Hara’s “For James Dean” (Collected 228-30), she is preyed upon by racketeers and other opportunists – including the racketeer Bugsy Siegel, and possibly Wieners’ own sister Marion. Wieners identified with the stars’ vulnerability to threatening “inferiors” – jealous people, dependent on but also determined to wreck their beauty and success. In “Ailsa’s LASt WILL and TESTAMENT”, the speaker laments “A marriage that never existed, a death under investigation,/ and a Fortune stolen from a M a d women in custody of itinerants.” This misfortune prompts him to ask: “Who could say wealth provides security, when the truth of one’s income/ lies upon inferiors”, and is threatened by “truth serums”, “innoculations”, jealousy (Behind the State Capitol 128). The celebrity poems are riddled with the vocabulary of hospitalisation, imprisonment, debt, war and political authority (one is signed Gerald Ford). They often include declarations of copyright, publication and performance. Such declarations licence them, give them formal status in systems of power which seek to extinguish them. But according to Wieners, the stars could also reconfigure reality around them. Their power could be read as a correlate of schizophrenic transitivism, projections of the individual’s wishes, desires, and self-image onto the world which make the real unrecognizable. But these poems are more than just schizoid projections and paranoid effusions: like O’Hara’s own poems for the stars, they explore the poet’s wishes, contradictions, desires and aesthetics in terms which implicate the culture industry and class conflict.

Adorno and Horkheimer argue that “The paradise offered by the culture industry is the same old drudgery. Both escape and elopement are pre-designed to lead back to the starting point. Pleasure promotes the resignation which it ought to help to forget” (142). The culture industry militates against transformative pleasure, or against the possibility of any exit from the uniform, repressive pleasures which make a lifetime mopping floors barely tolerable. Though he worshiped at the movie theatres, Wieners admitted that “There is a condition of mankind dependent on hallucinations in place of imagination. A condition of parasitism in place of contribution” (Behind the State Capitol 153). He recognised the price he paid for his devotion to the “hallucinations”:

Of course, while associating with actors and artists, in tyrannizing innocence and intelligence, especially of amateur means, then one must realize that the false glamour they create is often a lure to the overworked and underpaid. The excess I speak of occurs in the fields of medicine and hospitalization, where traitors to the United States possess power to defraud and bungle the orthodox recognition of errors and illegality within the processes of maturation and self expression. (Behind the State Capitol 163)

This elaborate but fundamentally lucid statement reveals the falsity of the promise of glamour and the consequences of testing orthodoxy: hospitalization. Those “traitors” who in the process of their own self-expression and maturation are lured to the excesses of glamour represented by actors and artists, “defraud” the system, and call into question the categories of truth and error, law and criminality. Consequently, they are punished. Throughout his work, Wieners speaks in the voices of celebrities, schizophrenia, poverty and addiction, dramatizing the difficulty of becoming a subject under the disciplinary regimes of late capitalism. This nexus of melancholic exaltation and depressed entrapment was, I will argue, partially sexual in origin. Horkheimer and Adorno also describe the representation of sexuality in the culture industry of the Hays Office era as “pornographic and prudish”: “the mass production of the sexual automatically achieves its repression” (140). The endless prolongation of pleasure, never achieved on screen, fixes the spectator in a masochistic position. I will return to the masochism characteristic of both Wieners’ and O’Hara’s poetry later.

The poems O’Hara was writing shortly before his death – “At the Bottom of the Dump There’s Some Sort of Bugle”, “Here in New York We Are Having A Lot of Trouble With the World’s Fair”, ‘should We Legalize Abortion”, “The Bird Cage Theatre”, “The Green Hornet”, “The Jade Madonna” and “The Shoe Shine Boy” – are also a pastiche of Hollywood dialogue. They construct from semi-moral aphorisms and broad American casualness a portrait of the poet’s wit and his familiarity with popular discourse. But his own thoughts, feelings, personality recede behind a stream of clichés which is most remarkable for its limitlessness. As in many of Wieners’ poems, in this sequence of poems the possibility of critique and reflection is sequestered behind a streaming linearity of excerpts, each disconnected from any previous unit, each building not to an argument but to an impression of the vapid and ceaseless bounty spilling out of the culture industry – a bounty as lacking in value as the commodities whose manufacture such poems knowingly imitate. The stylistic features of this late work bear a striking resemblance to Wieners’ later verse, and serve to remind us that its schizoid diction, style and versification make an important contribution to that work’s cultural critique.

Could Wieners be influenced by both O’Hara and Olson? In his sketch of the agonistic relationship between three “groups” in New York in the 1950s and 60s – the New York School, Black Mountain, and the coterie around Allen Ginsberg – Amiri Baraka suggests that he felt it necessary to choose an affiliation. He rejected the “Creeley-Olson types”, “people who took an antipolitical or apolitical line (the Creeley types more so than Olson’s followers – Olson’s thing was always more political)” (Benston 306). For Baraka, membership in one group meant disavowing another. Not so for Wieners. Pressed by Robert von Hallberg to say if he felt closer to Olson and Creeley or to Ginsberg and O’Hara in the 1950s, Wieners would only say that “I felt close to most writers in the 1950s due to my own youth. Any writer qualified for total embracing” (Selected 291).

Although many critics have contrasted Olson’s mythopoesis with O’Hara’s excavations of sociability and personal feeling,[5] Olson himself, in writing to Wieners in 1964, complimented that “nice Frank O’Hara whom I met for the first time last week, here, and he read so that every word, etc.”[6] Both Olson and O’Hara were fixated on the breath; Olson, taking a cue from Pound, believed breath to be the driving force of prosody, while O’Hara ended many of his poems with the intensity of breathing or held breath as a marker of intimacy and revelation. Olson was pleased to learn that O’Hara had grown up in nearby Grafton Massachusetts:

This seemed too much, that he shd join us old-fashion New England city-type poets instead of all that higher literature of both the immediate past here & abroad. (I don’t mean this, like, analytically, I mean that I was gratified he came of our own general sociology. For he was the other poet for all of us to have lived out the rest of this century by, simply that his tone and pitch was to be the lyre of this too, he was so capable of footing the measure once his feet were on the way.

Olson was presumably referring to Pound in making O’Hara “the other poet” in this letter to Bill Berkson. He added, “In any case the thing he and so many of you stand for is in fact, & will be seen to be the track literally of two say tracks only which this time in a person like him he so made clear—oh Lord I hate the fact that he will not continue to be a master”, again using the term of admiration, “master”, he reserved for Pound (Selected Letters 373).[7] While their poetic “tracks” might have differed, Olson clearly admired O’Hara for making clear his own “way” and his control of prosodic “measure”.

Olson and O’Hara’s work often appeared side by side. Both were published in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry, 1945-1960 anthology, in Floating Bear and Ed Sanders’ Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts, among other magazines. Brad Gooch claims (278-9) that it was Wieners who had prompted O’Hara to revisit Olson’s poetry, resulting in O’Hara’s composition by field of poems from the early 1960s like “To a Young Poet”. The letter from O’Hara included in Wieners’ memoir “Chop-House Memories” also makes reference to O’Hara following up “your tip on Lawrence”, an author Olson recommended in “The Present as Prologue” (Collected Prose 207).[8] O’Hara seems more skeptical about Olson, however, and writes cattily in “sudden Snow” (1960) that “the snow like Charles Olson working on one of his ABC poems/ is quietly and bitterly falling” (Collected 355). All the same, his question in “Hôtel Transylvanie”, “where will you find me, projective verse, since I will be gone?”, shows his familiarity with Olson’s essay, to which (Gooch again conjectures, 301-2) the “Personism” manifesto may have been a response. For all their differences, both O’Hara and Olson were articulating a new understanding of the poet’s relation to the present – to the present tense as a marker of transformative activity, and to the instant as worthy of improvisatory reflection. This interest in the present, and “the immediate past”, also affected Wieners.

Wieners’ own poetry could be read as a kind of X-rated Personism. Like O’Hara, he wrote compulsively and spontaneously, dwelling on love, disappointment, and desire. He believed that the material provided by the personal must be absolutely, simultaneously and shamelessly recorded; nothing should be left out. This belief also reflects Olson’s teaching at Black Mountain that “there are certain things which you hide from close friends and admit only to yourself; the task of the writer is to dig out those things which you will not admit to yourselves” (Duberman 371). Asked by Raymond Foye if he had a theory of poetics, Wieners answered “I try to write the most embarrassing thing I can think of” (“Introduction: Raymond Foye: A Visit with John Wieners”, Cultural Affairs 15). In “Parking Lot”, for example, he describes stealing $8 from Steve Jonas, which he pays to a man he blows, and then concludes, “Damned and cursed before all the world,/ That is what I want to be”. His explicit depictions of promiscuity are sometimes sweet or triumphant; sometimes, as in poems like “Memories of You” or “The Gay World Has Changed”, they are filled with self-loathing. This is hardly surprising, given the social intolerance of homosexuality, and his Catholic family’s condemnation of his sexual proclivities.[9] In an essay on “dangerous orgies and random, heedless sexual promiscuities of increasing despair upon a road to self-degradation”, Wieners reveals how the repression of homoerotic urges prevents the poet from reflecting on his own life: “Usually a homosexual, since he has been a stigma or outcast freak for so long, does not have a chance to meditate upon himself, even as a ‘straight’ citizen, with their usual rights or opportunities” (Behind the State Capitol 88). The explicitness of his poetry could be read as an effort to subvert heterosexist monopolies on public self-reflection, to meditate not only on himself, but on himself as a gay man, a stigmatized or “outcast freak”. But it could also be argued that the spectacle of the degraded self which he presented to “all the world” became another screen, a defenceless persona whose theatricality itself served as a form of defence.

O’Hara and Wieners shared this masochistic idiom; in their work, confessions of desire are often followed by fears of persecution, pain, and physical punishment. The comic aplomb of the runner in “Personism” may be a means of escape from traditional prosody, but for O’Hara and Wieners, writing often seems to feel like being chased down the street with a knife. O’Hara’s depictions of his own sexuality were often entangled with forms of discipline and fear. In “Grand Central”, the friend takes a “smoking muzzle in his soft blue mouth” (Collected 169); in “Hieronymus Bosch” (Collected 121), an allusion to fisting (“He puts his long/ fingers into the wet mandolin precious with lotion/ and stringy”) is followed by an image of lynching: “they dried him out and hung him up. My, he swung.” In his poem for Wieners, O’Hara describes the police following the strung-out poet, while jeering thugs and the “threats of inferiors” frighten him like “a Negro choosing your own High School”. O’Hara aligns the persecution of his gay friend with other forms of discrimination, here using Wieners’ own term for threatening and malicious hangers-on (“inferiors”).[10] As Ben Friedlander has argued (131-2), fear of homophobic attacks informed many of O’Hara’s references to race. O’Hara identified with victimised minorities, both in his experience of prejudice and in his desire to escape bourgeois mores. For him,

The impulse, the, at times, compulsion, toward normalcy must be avoided, when its fulfillment is known to be unsatisfactory, and when the level of endeavor is, as it is by definition, inferior to that possible through idiosyncratic behavior. One must live in a way; we must channel, there is not time nor space, one must hurry, one must avoid the impediments, snares, detours; one must not be stifled in a closed social or artistic railway station waiting for the train; I’ve a long long way to go, and I’m late already. (Early Writing 101)

For O’Hara, prosodic and imaginative speed are a means of avoiding entrapment and danger.

Wieners was infamous for the idiosyncratic behavior which O’Hara praises in this passage. In “Les Luths”, O’Hara publicises his admiration for Wieners’ work: “everybody here is running around after dull pleasantries and/ wondering if The Hotel Wentley Poems is as great as I say it is” (Collected 343). Wieners, shy but outrageous, was not prone to producing dull pleasantries.[11] Barbara Guest wrote that “I think Wieners had a special appeal for Frank, especially his madness” (Gooch 279). That appeal is apparent in “A Young Poet”, where O’Hara memorialized a visit by Wieners to New York. Strung out on benzadrine in the library, Wieners had become paranoid after spending “8 hrs with near every book S Noah-Kramer ever wrote” (a reading program notably influenced by Olson).[12] O’Hara may be remembering their meeting in 1956, and the publication of Hotel Wentley in 1958, when he writes:

Two years later he has possessed

his beautiful style,

the meaning of which draws him further down

into passion

and up in the staring regard of his intuitions. (Collected 278)

The poem makes two references to “the divine”: both the “divine trap” of poetic inspiration in which all Wieners’ admirers are compelled to believe, and the “divine prosecutor” who might dictate to Wieners his elegies. Again, the act of composition imperils the poet, “trapping” him and “prosecuting” him for his crimes. O’Hara attributes to Wieners a kind of vatic authority through his madness itself, reminiscent of the ancient Platonic concept of poetic fury. But he also predicts that Wieners, a poet whose intuitions included the psychoses of drug abuse and schizophrenia, would eventually be “exhausted by/ the insight which comes as a kiss/ and follows as a curse”. The erotic pleasure of creation first seduces the poet sweetly, but becomes “cursed” when it exposes the poet to the cruelty of the world, the revelation of its truths, or when it abandons him.

For both O’Hara and Wieners, the maddening commitment to poetry must end in death. Both poets fantasised about death, how it would unveil the extremity of their commitments to poetry, and punish them for their infractions against decorum, morality, or bourgeois taste. As his elegies for James Dean show, O’Hara was excited by the mythology of the fast-living, self-consuming icon, martyred by his own excellence, “racing” towards the heights of the gods (Collected 228). In another poem, O’Hara asks to borrow a “forty-five” and a silver bullet, the weapon that kills werewolves – men who turn by night into beasts. He then observes that “if you can’t be interesting at least you can be a legend” (Collected 43). Wieners clearly shared O’Hara’s live-fast-die-young aesthetic. In “Chop-House Memories”, he recalls accompanying O’Hara to Provincetown on the ferry to visit Edwin Denby. Both he and O’Hara “thought of suicide as the final resolution of our desire as we stood again below deck by the hectic Atlantic cutting at our feet, speaking of Hart Crane and the last words we would have in our mouths at that moment of surrender” (Cultural Affairs 80). It is notable that Wieners focuses on life as “desire”, and suicide as eliciting language (“last words”), in this pledge to enter the great tradition of self-destructive literary types. But the bravura of this conversation does not sustain Wieners in the truly suicidal moments memorialised in some of his poems. Although Wieners sometimes expressed a grandiose belief that “There is no age for a poet, that he exists outside of time, and is its watchdog” (Cultural Affairs 106), he more often worried that the moment of surrender was imminent, and that he with his experiences will be obliterated. “What one knows today will be gone tomorrow./ One reason to write”. As a justification for writing this is highly conventional: poetry outlasts brass monuments, is a deep mnemonic reservoir of all that eludes the biographical record. But Wieners has an additional anxiety prompting him to dwell on death: his experience of a generation that destroyed themselves with drugs (Selected 73). The future may hold imprisonment, hospitalization, or death by overdose; so “Do not think of the future; there is none./ But the formula all great art is made of.” Wieners legitimates his refusal to contemplate the future through an artistic tradition which values immediacy, as well as the suicidal self-destructiveness which he shared with O’Hara.

Wieners began seriously to court self-destruction when he moved to San Francisco in 1956. Raymond Foye suggests that heroin became widespread in North Beach that year, and notes that “Nobody had ever seen anyone throw themselves into the abyss the way John did”. Foye continues, “By the time of the Wentley poems Wieners himself is very heavily into drugs, taking grass, crystal meth, heroin, belladonna and a few other things, on a daily basis. According to Ginsberg, Wieners was intent on alienating himself from reality, with a vengeance; and, Allen claims, by 1959 W. had pretty much ‘blown his mind’.”[13]

Poetically, it was a productive time; Wieners regularly wrote during or about drug-induced hallucinations or described his interactions with drug users. Asserting that the deepest truths are available only to the unconscious and that the unconscious was accessible through drugs, Wieners recommended the altered states of drug hallucination or magical intuition as conditions for writing. The poet should wait for the words of the poem to arise “in middle of dream/ opium shadow curtains hang/ off eyelids, lips parched” (Cultural Affairs 52). Wieners cultivated this state of susceptibility, “drowsy and half-awake to the world/ from which all things flow” (Selected 159). But after an initial period of idealism about drug use, he became suspicious of such trance aesthetics. He found it “very hard” to review Clive Matson’s Poems for Floating Bear,

cause (his poetry springs out of a “narcotic” experience, or milieu, I mean it’s toughness, that isn’t natural to him, and which he has gone to junk for.) [… ] (I got thrown into junk for glamour and pain yes, because it led to new experience, and because the people I loved were using it, and the nature of “evil” is such, that it is contagious and infectious.) Can I say that? (But to take on the pain of the world, is not right. One should obiate, or obviate suffering, not induce it.) Don’t you think?[14]

He was drawn to junk for the same reason he was drawn to the stars: “for glamour and pain”. Once rehabilitated, he recognized it as “evil”, an infection, which exposed the poet to the pain of the whole world.

Although Wieners eventually broke his drug addiction, he became chronically afflicted by mental illness. After an opium- and benzadrine-fuelled roadtrip from San Francisco via Washington and New York, he found his way back to his family home in Massachusetts. He was then hospitalized from January to July 1960 at Medfield State, and from March to August 1961 in the Metropolitan State Hospital, where he was treated with electric shock therapy.[15] The poem “Untitled” (Selected 226) says that his parents borrowed $900 for this painful and ineffective procedure in a private sanatorium. Wieners described himself as

Pierced with a miniature electric track

on which no trains run

our back against the wall

this shock treatment does not cure

as it’s supposed to

Only reduces sustained intellectual effort

and turns poets into dogs.

After he had recuperated, he moved to New York in 1961. Diane Di Prima writes, “Irving Rosenthal brought him over I recall, and we hit it off. John’s story was tragic, but familiar, too. His Boston Catholic family had had him committed for being gay, and using dope, maybe junk, now, all those shock treatments later, he was more than a little crazy”(272-3). If Di Prima thought the treatment had made him “crazy”, Wieners himself worried that it had killed off his poetic abilities. Depressed, lonely and living with his parents in 1965, Wieners confirms that “Now that life no longer provides means for poetry, I am caught within my mind. And it is not enough. With the shock-treatments and drugs. It never was, even before”.[16] For a poet who believed that poetry emerged from the magical subvention of reality, the deadened consciousness maintained by pharmaceutical treatment and electric shock was more frightening than the delusions of dope and madness.

In San Francisco, Wieners had picked up not only a heroin habit, but also a magic vocabulary to describe the effects of his variously transformed consciousness. For Wieners, poetry was like the tarot, junk or schizoid delusions in its power radically to transform the world. A statement “written for Robert Creeley’s class of August 17/72” describes poetry in terms similar to his description of the Marian movie star: poetry is “the most magical of all the arts. Creating a life-style for its practitioners, that safeguards and supports them”. In one poem in Floating Bear 10, Wieners directs a magic ritual to bless his bond with O’Hara. He invites O’Hara to join an occult ceremony which starts with a public declaration of affection and invokes blood, astrology, dream and “freedom”:

We hold hands on the street in the dream I never passed

the sun stone to you. Who stomps for freedom and the

rites? Three times right around the stone (only a capricorn’s

blood can break) it’s yours.

Holding hands, they declare their affection publicly; they are both “free” to show their love and bound by an esoteric “rite”, which closes their relationship to the rest of the world. Wieners marries O’Hara to himself, replacing the orthodox ceremonies of commitment with his own magic vocabulary.

This desire to establish a bond with O’Hara is understandable, given Wieners’ frequent references in his poetry to the sorrow of abandonment and the unreliability of his relationships. Often he attributes this to his lovers being kept away from him by their families; consequently, he not only wants a wife; he wants to be one. The bond of marriage is, he says, a kind of sacred ownership. In “Gardenias”, he confesses that after “two decades of drunken futility”

still some loneliness lingers as sickness’s vapor—

is it jazz, or late-night musings by the harbor,

unemployment with an empty head in the library

merely only poverty, or could it be the inability

to hold a man, or woman as my own property? (Behind the State Capitol 62)

Whatever the answer, “I am sick of sickness in the heart,/ having no part in the world, being only a victim/ to time, money, and machines made by men other than I.” He is excluded from marriage, the one form of property relations which will liberate him from hunger, loneliness, and exploitation. “Forthcoming” (Selected 110) laments that

I died in loneliness

for no one cared for me enough

to become a woman for them

that was not my only thought

and with a woman

she wanted another one.

The concluding reference is probably to Panna Grady, whose shattering effect on Wieners is described below. But he also regrets that his lovers have not asked him to become a woman – to dress up for them, nurture them, be at home when they return, enacting the rites of bourgeois family life.

“I have a woman’s/ mind in a man’s body” (Cultural Affairs 58), he repeatedly affirmed. The feminized persona allowed Wieners to express both his relative powerlessness as a lover or as a “mentally ill person”, and his desire for power through beauty which he associated with stars like “The Garbos and the Dietrichs”. The big screen celebrity never has to experience material or emotional lack; she can avoid tedium, loneliness, ugliness. She lives thoroughly and permanently in a condition of emotional and aesthetic intensity which Wieners himself can only recollect, her powerfulness accentuated by her distance from her admirers, her image mediated by print, film and magazines. His own fantasised position relative to these Hollywood beauties is both intimate and masochistic. Wieners wishes to be “a gossip, a behind-the-scenes man who knew all the stars, was able to enjoy their carryings-on, and to participate in the difficulties of experience in our contemporary society”; he is hypnotised by Rita Hayworth, who generates “unending desire” in him, and turns him into “a passive slave to her wishes, knowing I’m unnecessary to her” (A Superficial Estimation 12). He is also personally related to them: he is Elizabeth Taylor’s sister, Barbara Stanwyck’s neighbour, Bette Davis’ daughter. Unlike some of the starlet poems of Behind the State Capitol, where the addition of the star’s name at the end of the poem attributes the poem’s extravagant claims to an extravagant persona as a kind of comic detournement, these poems adopt the celebrity identity as part of a mundane, domesticated or familial fantasy. He sees Elizabeth Taylor in a bookshop; “Never once in the thousand times we have met” has she refused him anything. Rita Hayworth meets the “inexorable” demands of stardom and the speaker’s “attempts to conduct myself as an adult” with patience as they move around town together.

His poems written in the voice of Lana Turner or Elizabeth Taylor bear formal similarities to O’Hara’s poems “Portrait of Grace” and “Jane at Twelve”. In a technique which Wieners himself would adopt, O’Hara punctuates the baroque formality of hortatory lines like “Let not that firebrand/ stolen from the summits mark her brow” with more earthy descriptions of a woman “decisive like a lightbulb” (Collected 88). But where Wieners inhabits the female personae of his poetic fantasies, O’Hara renders these idealised females in violent, surrealist terms. The poems alternate between the declarative powerfulness of a male poet describing an otherworldly “she”, and that she being given leave to speak of her own experience from the perspective of an “I”, in terms whose very syntax and diction corroborate the original assertions of the male voice. What differentiates Wieners’ poems about the stars from O’Hara’s is the quality of their sympathy. Lana Turner may have collapsed, but for O’Hara the tribulations of Hollywood are mostly available to comic speculation. His benedictions – “may the money of the world glitteringly cover you/ as you rest after a long day under the klieg lights with your faces/ in packs for our edification” (“To the Film Industry in Crisis”, Collected 232-3) – are sprinkled from on high. By contrast, Wieners’ increasing tendency to identify with the stars has to be read in the context of his depictions of, and identification with, the underclass who serve as their foils.

Wieners’s Hollywood poems express his desire for freedom, for the liberty to travel and to act, as well as empathy for the restraints and exposure which a celebrity lifestyle imposes. His flamboyant resistance to respectable bourgeois mediocrity was expressed in his dress, his conversation, and his desire for absolute relationships both with his lovers and his poetic mentors. That resistance – a dramatic enactment of the desire to be seen as unique and differentiated – takes on a political character in the context of his frequent hospitalization. People, he told Charles Shively, “are in those institutions just because we have created stereotyped roles of what people should look like; what they should wear; how they should converse.” The patients’ failure to abide by those stereotypes “imperils the ordinary citizen on the street” whose identities are manufactured out of conformity with the stereotypes, and leads to their incarceration (Selected 293). Wieners implicates his own appearance alongside the

dwarfs, who cannot stand up straight with crushed skulls,

diseases on their legs and feet unshaven faces and women,

worn humped backs, deformed necks, hare lips, obese arms

described in “Children of the Working Class” (Behind the State Capitol 35-6). In this blazon, the deformed citizens of a society which values glamour are subject to the poet’s gaze, just like the stars who grace the pages of women’s magazines. Beauty and monstrosity, conformity and nonconformity are alternate and equivalent disciplines.

That Wieners’ poetry rotated between such idealized and negative realities may express something of the psychic conflict which his sexuality produced, in his family and himself. Wieners venerates the “wrapped up romance” and refreshment of a gay bar in “The Gay World Has Changed” (Selected 248), but he still must insist that

The men, normal looking enough, you”d never know,

are not degenerates, good clothes with intelligent con-

versation

against the voice in his head which hisses: “you’re a faggot, a faggot, you’re nothing but a homosexual,/ nothing more; sex, sex, Sex and sex.” However well they and he observed decorum and style, a voice of normalizing morality keeps insisting on their “degeneracy” and “dirtiness”. But the movie star constantly obeys decorum. “How Perfect, How Quintessential!” (Selected 251) describes Ava Gardner’s living room in Madrid in the language of the glossy celebrity profile. The room has “the proper paintings, the correct books”, observes a disciplined and appropriate aesthetics. But why should such conformity appeal to a writer who himself cultivated the inappropriate, the indecorous, and the maladjusted? “Unsterile, who would this photograph have been taken for,/ if not to titillate our collages in the frames, our poverty-starved suites,” he concludes. Wieners’ poetry plays in the gap between poverty and wealth, between his messy collages and their tidy, controlled source images. He was aware of the penalties for misappropriating the glamour possessed by the stars: he had even been arrested for impersonating Ethel Kennedy at an airport.

Wieners wrote that Lana Turner “travelled fast”. As for O’Hara, speed was an expression of ultimate freedom. Travelling fast was not only a condition of physical and social escape, but also a poetic impulse. After the syntactic and lexical economies of Nerves, many of Wieners’ later poems are dominated by polysyllabic words and convoluted syntax (“Attic coiffure admonitioner/ supreme Parisian commissioner/ unblemished saviour’s listener”, for example). In such lines, the clutter or collage of sound and sense is produced from a superabundance of free language. While psychologists identify schizophrenic speech as highly rhythmic and rhyming, with a tendency to perseveration (Cohen 18), such syllabic pile-ups in Wieners’ poems share with readers the complex semantic possibilities and luxuriant aural properties of language, made available when the ratiocinating consciousness lets go. It cannot be overemphasised that what might be diagnosed as perseveration in a poet known to suffer from schizophrenia is often revered as complex and artful play with the texture and sound of words in the work of Wieners’ contemporaries. In many of Wieners’ later poems polysyllabic words tumble out with little apparent semantic logic; personal pronouns are avoided; asyndeton emphasizes the sonic textures of his diction, especially the similar suffixes or rough consonance which hook individual words to each other. This work shares many characteristics with a poem like Ashbery’s “Europe”, but for that poem’s sequence of prominent lacunae Wieners would always substitute a tangle of nouns and attributes selected for their jarring or consonant sounds. It also bears comparison to poems by O’Hara such as “Dido” (Collected 74-5), where parataxis feeds the flood of consciousness, words urgently vault over the absent syntactic or semantic connectives to produce a sense of urgency. The frenzied pace of O’Hara’s prose poem, its associative structure and sociability combined with its morbidity, resembles Wieners’ techniques. So, too, does the camp feminized persona:

I could find myself rallying ground like pornography or religious exercise, but really, I say to myself, you are too serious a girl for that… If, when my cerise muslin sweeps across the agora, I hear no whispers even if they’re really echoes, I know they think I’m on my last legs, “she’s just bought a new racing car” they say, or “she’s using mercurochrome on her nipples.” [… ] But if this doesn’t cost me the supreme purse, my very talent, I’m not the starlet I thought I was. I’ve been advertising in the Post Office lately. Somebody’s got to ruin the queen, my ship’s just got to come in.

The starlet is down on her luck. Listening for whispers of admiration as she walks through the marketplace but hearing none, she turns to consumption (buying a racing car) to contradict rumors of her decline. The use of the first person invites readers to consider how O’Hara is “advertising” himself, his talents and his looks, in the office of letters; and how the abundance of ideas, phrases and images in this poem is a kind of conspicuous consumption to stave off rumors of his own defeat.

Many of Wieners’ early poems use ornate, formal diction and convoluted syntax, but (as we have seen) he increasingly adopted celebrity personae and associative patterns of speech and imagination. It may seem surprising, given his experience of street life, drug use and the gay subculture and of their vocabularies, that Wieners so often used archaic idioms. His ornate formality was partly camp. Many of his poems modulate between antique, deluxe idiom and slang or concrete detail; slang differentiates real, nasty life from fantasy, brings the poem tumbling back down to earth. In “The Waning of the Harvest Moon”, for example, the unspecific and formal address to “daughter my soul” is broken suddenly and effectively with a confession of violence and covetous poverty: “I want to go out and rob a grocery store” (Wieners, Selected 58). Such modulation is generally not a declaration of equivalency between fantasy and reality, but of the conflict between imagination and instrumental reason. In “A poem for cocksuckers”, the queer bar is a utopian space within a city where hostility to homosexuality is still the norm; that utopia is defined through the poem’s own remastery of abusive language (“niggers”, “fairies”, “cocksuckers”). By placing such words in the frame of camp or ornate language, he neuters them. The poem moves away from violent slang and the detailed, specific interior of the bar to a fantastic pastoral realm of fountains, rivers, mountains and springs. Wieners concludes that it is only by abandoning the specific for an idealised landscape produced through associations that the poem can fully express the “gifts” possessed by those around him.

His syntax itself is fraught with this clash between idealism and realism. Though Olson advised him early on that “I’d put back yr original straightness of syntax”,[17] Wieners regularly uses archaic grammatical forms to call attention to the artificiality and insufficiency of his idealized wishes. “When green was the bed my love/ and I laid down upon,” he writes in “A poem for painters” (Selected 31). The compound preposition “upon” is one of his favourites, used three times in this stanza alone. Such poems are also consistent with this veneration of the stars: they provide luxury at the syntactic level. Where shifts between outdated diction and contemporary slang highlight the gulf between fantastic alternatives and grim reality, this luxurious and outdated syntax provides a poetic architecture similar to the bountiful and inaccessible realms of the cinema stars. Antique language also locates an idealized past in poems which celebrate immediacy. Though Wieners embraces the sexual liberties achieved by changing social conditions and the gay rights movement, he is also a poet who regularly expresses his desire for failed marital archetypes. The archaisms of his diction and syntax, by evoking older kinds of discourse, also appeal for the older, more genteel relations established within those discourses.[18]

Despite his use of old-fashioned language, Wieners declared himself to be a poet of the present – of the instant unmediated by scholarly reflection, an oppressive sense of literary history or even concerns for the future which might necessitate planning (of his life or his writing). Here, he may resemble O’Hara; but just as it would be reductive to regard O’Hara’s poetics of the present as a simple “I do this, I do that” formula, so Wieners regarded simple “description” of the moment as “a deceit. An easy/ trap to fall into” (Selected 70). In “Confession” (Selected 74), he writes

I remember

Wednesday afternoon when we walked

in the sun and heard the girl sing

Stormy Weather. Mere description

but spirit of the night, teach us

to bear despair.

The almost guilty shift from “mere description” of the O’Hara-style perambulatory opening, through the short conjunction “but” shows how close to the skin this despair lurks – any poetic occasion can trigger it. But it also suggests that Wieners is poetically and emotionally habituated to invoking that despair: it is the ruling topos of his literary and psychic life. Wieners’ attitude to both description and despair is conditioned by his understanding of the present. As he writes in “A poem for record players”, the effluvium of life is its “dull details/ I can only describe to you,/ but which are here and/ I hear and shall never/ give up again” (Selected 27). The excruciating beauties of the present, if they are not shared, can only be described, though they remain in the memory of those who experience them as a site constantly to be revisited. Wieners was certainly aware of Olson’s insistence on regarding the present as “prologue” to a future determined by the activities especially of poets. But unlike Olson, who sought to recover the past through creative scholarship, Wieners regarded the past as “a vapor that escapes/ from the mind in impatience” (Selected 156). Like O’Hara and other New York School writers, he had limited interest in Olson’s serious projects to excavate the past. O’Hara himself describes the past as “really something” (“Biotherm (for Bill Berkson)”, Collected 446) because you can remember it honestly or “you can/ lie about everything”. In this sense, the past is poetic – O’Hara may be remembering Plato’s description of the poet as a bad liar in Republic book 2. Later in the poem O’Hara contemplates the “long history of populations” but quickly turns to making fun of scholars who misidentify German-language books as “sanskrit or Urdu” and end up brawling while “the dark was going on and on” outside. In what could be read as a poke at Olson, this teasing eventually turns into a pseudo-etymology of English.

Wieners found in O’Hara’s glorification of the present an alternative to Olson’s intellectual scrutiny of the past. In his statement for Donald Allen’s New American Poetry anthology, Wieners advised that “one cannot avoid the/ days. They have to parade by in all their carnage” (Allen 426). O’Hara was a poet who watched that parade of days, not shrinking from their carnage or retreating into academic speculation. In an essay he sent to Olson, Wieners clearly identifies his own poetic vocation with what he awkwardly calls O’Hara’s “triumph of will” over those persecuting forces which seek to “dominate his imagination” or his existence.

The world of the intellect or sensibility is excruciated. The poems of Frank O’Hara seem as valid testimony in the face of this <violet crushed against a skyscraper>. All poets do their work is a triumph of the will over those who seek to dominate <their imagination> or limit their potentiality possibility of existing, all day.[19]

O’Hara’s will to work among the skyscrapers which would “crush” his delicacy, represents for Wieners the possible triumph of imagination over the grim conditions of modernity. His “triumph” is his capacity to exist, “all day”, wholly in the present, as exemplified by Wieners’ unironic reference to Leni Riefenstahl’s film. Charles Altieri has described O’Hara as depicting “the present as landscape without depth”: “And if the present is without depth, whatever vital qualities it has depend entirely on the energies and capacities of the consciousness encountering it” (Altieri 110). But where for O’Hara that present-as-cityscape is a constantly changing, exuberant superficiality against which a variety of transient subjectivities can play, for Wieners the depth of the present is filled with memories, patterns of loss in which his subjectivity is pathetically fixed, despite the many characters he plays. Those characters seem chosen precisely for their unsustainability, to mark the alienation and lack which stain his private life. Despite his valorisation of the present through occasionally paranoid or mystical sense of immediacy, he cannot abjure the past completely.

If his acknowledgement of the past is limited only to personal memories and anachronistic diction or syntax, then Wieners owes little to Olson and much more to O’Hara’s poetry of specificity. But he explains his real debt this way: “Before Charles, I practised a hands-off policy in terms of my experience… I was looking inwards, rather than gazing out” (“Twenty Hour Ballet”, Cultural Affairs 135). Wieners simplified Olson’s argument – that the personal and the impersonal, the world and the self, context and soul are both spaces which can interpenetrate each other[20] – via LSD and opium into a negation of the importance of distinctions between the real and the imaginary, materialism and idealism. While Olson’s art implicated his own life in the epic of history, Wieners’ elision between poetry and the “estates of being around us” became a chronicle of collapse into schizophrenia. Olson recommended “objectism”, defined as “getting rid of the lyrical interference of the individual as ego, of the ‘subject’ and his soul” and being able to listen to the identity between himself and the world. Wieners did engage in such listening for the “secrets objects share”, but through the magnification of his own ego’s lyrical interference, not its obliteration. In fact, in addition to being a ripe poetical technique, collapsing the boundaries between “himself and world” is, according to Kleinian psychoanalysis, part of the faulty process of projection and introjection inherent to schizophrenia.

Olson believed that Wieners was always in danger of being too personal, relying on the insights of his occultized inner life rather than the deliberated products of study. Sometimes Olson spun it, as Robert Creeley remembered his talk at SUNY Cortland, as a distinction between the poetry of art and the poetry of affect.

He spoke of such poets as Wieners John Wieners as being poets of affect in so far as the daily life daily lived and its im agination it wasn”t simply stuck with that but it did not metaphysically propose a conclusion. It wasn”t working towards an end in mind. The mind was used to make the mind was used to not merely to record but to work on what is. (Spanos 16)

Wieners did not write through the mediation of precepts, or of systems for comprehending history and language; his poetry translates, with sometimes unbearable immediacy, the events and non-events of present personal life into a sustained argument about the alienation and loneliness intrinsic to a fallen human condition. It reads the body as a map of such moral convictions. In this way, his were eminently metaphysical concerns.

Perhaps this reflects the symbolic repertoire provided by his Catholic upbringing. The secularist Olson challenged Wieners’ occult and mystical obsessions, but he was also sensitive to the hardships Wieners faced. His essay “The Present Is Prologue” acknowledges that how any of us “make ourself fit instruments for use” is affected by the family (both immediate and historical): “what strikes me … is, the depth to which the parents who live in us (they are not the same) are our definers. And that the work of each of us is to find out the true lineaments of ourselves by facing up to the primal features of these founders who lie buried in us” (Collected Prose 206). Olson wrote about one of Wieners’ poems in 1957, “I feel defenses here which, I took it, the spring was the time to dissuade. (I dare say it is the environment?” This surmise – that Wieners’ poetry was defensive on account of the hostility of his family – is corroborated by many of Wieners’ own journal entries and poems including “Two barbarians” (Selected 240-241). At the same time, Olson symbolised for Wieners the challenge of repudiating the immediately available knowledge of the heart. With reference to “The Present Is Prologue”, Wieners describes his “master” as being

the first to recognize

and save me from the self condemnation I practiced

Let me know the chambers of my soul. (Journal 49)

Olson’s poetics legitimated the dissociative patterns that increasingly affected Wieners’ thinking. Wieners was still citing the “Projective Verse” imperative that “one perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception” in a letter to Hank Chapin in 1962,[21] and in the poem “Ma’s Deck Chairs” from Behind the State Capitol. He described himself and Olson as “different sides of a coin, reversed in spirits” (Selected 292). He was faithful to Olson’s emphasis on “feeling and desires and breath” as “the cause of the words coming into existence/ ahead of them” (Olson, “Human Universe”, Collected Prose 202). His review of Matson celebrates

Breath, and the practice of it. Form is not of the question here.

Jazz, and its mainline to the heart.

While the first occasion for celebration is typically Olsonian, the second is closer to both New York writers and the Beats. As he explained about his poetry’s rhythms, “the gauge is intellectual”, not respiratory: he rejects Olson’s veneration of the breath, because “the breath is so relative” (Selected 290).

Despite the debt he owed to Olson, Wieners sought to differentiate himself from his “master” the “sage”. After leaving Black Mountain, he wrote in gratitude to Olson, “somebody like me doesn’t get what those three months gave, and walks away to a less-kind of world. He walks with it between him and the ground”.[22] But soon after, he resolved – just as Olson had overcome his own “master” Pound – “Damn the references to my lords, I must set myself up as absolute” (Journal 62). When The Hotel Wentley Poems was published, Olson praised its “delicious recked exciting split seconds throughout.”[23] A series of poems written over the course of a week in a flophouse, Hotel Wentley showed a command of the short and regular line which owes little to Olson’s projectivist prosody. Although the stanza beginning “south of Mission” in “A poem for Painters” evokes Olson in its panegyric to the rolling American landscape, these poems are about the introverted subject, not about the heroic destiny of Americans as a first people. Rather, they take an inward voyage into “the Place/ of the heart where man/ is afraid to go” (Selected 34) but which the drug sub-culture makes inhabitable, the “dark places” of a primordial self. Nonetheless, Olson admired the book as “really on, in a French way which lighted up his natural sensational Irish powers to the plums stayed on trees, instead of falling off and rotting all over the ground (no matter what fine grass I thought that made, the next season, anyway!)” (Selected Letters 263). By their “French way” Olson probably meant their imitation of Rimbaud. In a notebook entry probably written in 1965, Wieners resolved to “be the new Rimbaud, and not die at 37 but set the record straight, new words to music, <nor Hart Crane either,> the key to existence”.[24] Rimbaud’s famous dictum “Je est un autre” epitomizes the violent estrangement from a sentimental self which also characterizes many of Wieners’ drug poems. Olson had recommended Rimbaud to Wieners at Black Mountain, as a poet who restored the law laid down by Heraclitus and “vitiated by Socrates”: “that man is estranged from that which he is most familiar, that like Rimbaud said we are all niggers, and, as I added, we treat ourselves cheap”.[25]

After Black Mountain, Wieners and Olson lost touch; but they renewed their friendship at the Berkeley Poetics Conference, and Olson invited Wieners to join him at SUNY Buffalo as a teaching assistant in 1965. The year in Buffalo was in some ways productive for Wieners. He was part of an active writing community, and looked forward to the Spring Arts Festival, whose participants included Jean-Luc Godard, Nam June Paik, Michael McClure, and Taylor Mead. But he revealed his mounting paranoia in a letter to publisher George Minkoff:

I have all kinds of irritants here; the drug-addicted undergraduates at the State University fill every evening with pain, screaming and offal. As a descendant of the original designer of the town, I am horrified at their behavior, ex-convicts and thieves particularly from Long Island and the Bronx. I have been persecuted by them for twenty-five years, so desperately turned to poetry as a means of revenge.[… ] To have these undesirables in town hinders mobility at the theatre, museum or concert hall, but I still attend, and if I could afford would purchase season tickets for all three. Someday that will be my usual activity. As it is now, the air is rent with parasites and I look to these opportunities for relief.[26]

Wieners relied on Olson’s friendship as well as the theatre, museum and concert hall; but he later wrote “I fear that I drove him out of Buffalo with my obsessive attention. We seldom allow what is beneath our dignity. I was pretty low class at that time, rooming above a clothing store, using Mister Olson for many things” (“Hanging on” 23). At this point, Olson’s relation to Wieners was not entirely supportive and benign either. After the pleasantries of their trip to Spoleto, Italy, together, Olson and Wieners fell out in 1966. Wieners had set up house with Panna Grady and her daughter Ella in Annasquam, Massachusetts. Olson wrote to them as “Romeo und Julia auf dem Dorfe” from Gloucester on 26 June 1966: “Please send the following message to your newly weds—the fullest & deepest realizations of the joys and fruits of the marriage ceremony”. Though they were not married, the fruits of the ceremony were planted; Grady was pregnant. She decided to return to New York for an abortion. Wieners was devastated, describing that event with uncharacteristic violence in “Alcohol doesn’t see… ”, “Sunset”, and “Maine”.[27] His long-held wish for “a wife and home” (“Supplication”, Selected 125) seemed unlikely ever to be satisfied; and the beautiful heiress, who had temporarily fulfilled his fantasies of the glamorous woman, had betrayed him. The misogynist aggression of a poem like “The Garbos and Dietrichs” (Selected 101), with its reference to “odd pregnancies/ abortions are not counted”, shows how all his former goddesses were degraded by these events. His journal from this period is filled with rambling, violent improvisations on his unhappiness and Grady’s treachery.

The last poem in the journal is “Billie”. The man who “as a god/ stepped out of eternal dream” to steal his girl was none other than Olson himself. The next letter from Olson (18 November 1966) found Wieners in Buffalo, and his mentor “two weeks here in London on Piccadilly no less until things clear; Panna purposeful to finish London—& I as you know determined to spend the winter in healthy climate: England’s too cold for me!” The cheerful weather report did little disguise Olson’s betrayal. When he returned to SUNY Cortland to give the lecture discussed by Creeley above, Olson wrote to Harvey Brown about his nervousness at seeing Wieners again:

Off today to do that stint before 70 New York State (College I suppose poets—including I hear one John Wieners. So hold your breath—I’m not sure I shldn’t have you along as my bodyguard, at least to frisk him unnoticeably! (Letters 389)

Later, he reports with relief, “saw John & he was just as usual too much. Read marvelously—& was more than ever my Admired One! Though his hair is now Henna Bardol I mean Clairon I mean Neponset Bleach—& there are three teeth hanging in his front mouth.—He is sharp-tongued & swollen with hurt-pain & feeling, but anybody who can’t see he is quicker & more profound than ever are themselves fools!” (390). Wieners also wrote enthusiastically about the meeting,

It was so fabulous to meet after a year when I thought – all love I had told him my years as a student were over, 12 in all, last summer 1966. Now our friendship may start. It was never that before as I was in such awe, I could never contribute anything but audience. Last weekend held delight – maturity, sophistication. Expect to honor his birth this December as always.[28]

Later, in a memorial to Olson, he wrote magnanimously that “I came to Gloucester with a girl, Panna Grady, who has since become Mrs. William van O’Connor in Paris. She studied his work as well as I and he came to call on us frequently that summer of 1966, until they sailed for London on the Empress of Canada in the Fall from, I believe, Montreal. It was not an unhappy time, I see in retrospect, for any of us” (“Hanging on” 23).

Although the letters to Olson in the late 1950s and early 60s employ many of the older poet’s idiosyncracies of lineation, syntax and punctuation, after the sorrows of 1966 Wieners found his own independent style in both correspondence and poetry. The memorial “Hanging on for Dear Life” explains its admiration for the older poet negatively: “Charles Olson has not for me since his death, become a colossal bore” (Behind the State Capitol 14). It praises Olson for “his navigator’s tools or pilot’s compass for charting the depths of unfathomed waters, see[k]ing to steer a man straight. I am not going to make the compromise of seeking love on strange shores, just because it’s available. It doesn’t of necessity follow that available means are the most satisfactory”. This ambiguous statement at once indicates the value of Olson’s “tools” for poetic discovery, and the usefulness of more than “available means”; but it also rejects the “compromise” of exploratory poetics, choosing instead love and familiarity. While Wieners’ gratitude to his mentor resonates in many such commemorative statements, this ambivalence also indicates that Olson’s betrayal had given Wieners an opportunity to escape the teacher-student relationship for one of greater self-assurance and equality. When Olson died, he composed an elegy “Charles’ Death”, which concludes

I could not believe he would die

even though my dream had come true

and he had fulfilled so many.

Is “my dream” partially the fantasy of Olson’s death itself? The edgy narcissism of this tribute – that Olson’s mortality was incredible even though he had in a sense completed his work by fulfilling the dreams of Wieners and other poets – suggests that such ambivalence remained even after his death.

I have characterised the relationship between Wieners and O’Hara and Wieners and Olson as (mostly) sympathetic friendships, with O’Hara’s cosmopolitanism and humour taken to extremes in Wieners’ obsession with Hollywood and camp melodramatics, and Olson’s emphasis on the present and the personal providing the springboard for Wieners’ early Rimbaudian writing. These are just two of the vectors of influence and collaboration which can be drawn from Wieners’ writing, and I hope this essay will encourage other critics to take another look at this work. It is too easy to take the poetry of John Wieners for granted, sketching its trajectory as a drug-induced shift from the occasionally overblown formalism and luxuriating archaisms of the early works to the schizoid associations and chaotic referentiality of the late. Along the way, despite the careful prosodic controls of the volume Nerves, Wieners might be seen as an introvert who is redeemed from ultimate narcissism mostly by the sordidness of what he is willing to reveal about his own desires. He has been described by Ginsberg and Creeley as magically gifted by his own drug psychosis and mental illness. In his foreword to the Selected, Ginsberg plays Shelley to Wieners’ “Keatsian eloquence, pathos, substantiality, the sound of Immortality in auto exhaust same as nightingale”. Creeley likewise described his poetry as “in the process of a life being lived, literally, as Keats” was, or Hart Crane’s, or Olson’s own” (“Preface”, Cultural Affairs 11). While some of the features of Wieners’ writing can be attributed to his derangement of the senses through drugs and later his mental illness, these features are above all filled with critical artistry which draws on currents in contemporary writing and aesthetics. It is only by reinterpreting such diagnostics within the larger field of his technical and thematic experimentation that we can really understand the poetry of John Wieners as more than torch-songs by an original who jeopardized everything for his art. His dramatic self-presentation owes something to O’Hara, though his poems can lack the improvisational comedy of O’Hara’s Meditations in an Emergency. And while his engagement with his own past lacks the complex historical sweep which gives Olson’s work its epic grandeur, it nonetheless exemplifies the “mind, that worker on what is” in ways Olson might never have anticipated. But I hope these similarities do more to situate Wieners’ controlled artistic intelligence than to limit his achievement. As a chronicler of the ups and downs of the early gay rights movement, as an aficionado of the culture industry, as an incisive critic of state institutions and social perceptions of mental illness, and as an artificer whose syntax and diction expressed the profoundest state of alienation and profoundest hope for love, his poetry stands alone.