James Keery reviews

The Failure of Conservatism in Modern British Poetry

(Salt Studies in Contemporary Poetry series)

by Andrew Duncan

ISBN 1876857579; Salt Publishing, Cambridge UK, 2003, 356pp. GBP 19.99, USD 29.95

This review is 7,000 words

or about 15 printed pages long.

A different view of this book is provided by David Kennedy in Jacket 26.

1: ‘Diminishing Returns of Febrile Excitement’

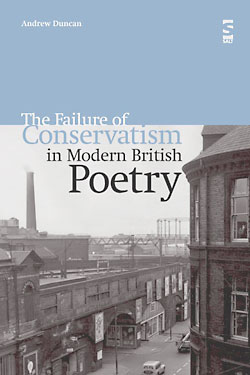

The cover of The Failure of Conservatism in Modern British Poetry presents three horizontal bands of colourless colour, grey-blue, light grey and dark grey, like a Rothko by Larkin. The two lower bands consist of a monochrome photograph of a railway station, the oppressive grey-black bulk of the station hotel occupying the whole of its right-hand side. Removal of the top band would leave the coherent and rather beautiful cover of a book entitled ‘Conservatism/ in Modern British/ Poetry’. Elegantly right-justified, the words are presented as an authoritative slogan against the light-grey sky, the word ‘Conservatism’ in 36-point grey-blue type and the word ‘Poetry’ in 48-point funereal black. Its solid letters echo and intensify the uprights and curves of chimney, arch and lamp-post. The subliminal message reads: Vote Conservative — Vote Larkin!

Post-war austerity and functional drabness could scarcely be more faithfully depicted. There is no one in sight and the smoking factory chimney rising above the grim façade is the nearest thing on offer to a point of interest. Unless you take a closer look — in which case you can just make out the design on the advertising hoarding in the bottom left-hand corner: a giant light-bulb, wearing a party hat. Looking very much the worse for wear, it is grinning all over its face, as well it might. The illumination of jouissance!

The ironic caption of the first three words, in 26-point white type, placed right on the horizontal of the image, promises an anatomy of why ‘Conservatism isn’t Working’, yet Duncan’s deepest preoccupation is with all that is thrilling, beautiful and new. His thesis, to reduce 300-odd closely argued pages to a sentence, is that the year 1959 saw the beginning of a brilliant era in British poetry, which has yet to run its course. Duncan stands out from the crowd of laudatores temporis acti who praise new writing — if at all — only at the expense of ‘most of what passes for poetry nowadays’; and equally from the copywriters whose praise of the latest batch of ‘pod-people’ is worth even less. For all its seriousness, the spirit of this book is close to that of Glad Day, which famously adorns the cover of an infamous Sixties text:

In 1969 came Children of Albion: Poetry of the Underground in Britain (Penguin, ed. Michael Horovitz); perhaps the worst book I have ever read. This was a close-up of a disaster, and may explain why the poetry of the 1960s remains neglected and unrevived; Penguin have not revived it. However, even this contains early work by four of the poets included in A Various Art in 1987, and hailed then as the intellectual avant garde… You can’t understand the roots of A Various Art… without seeing the spontaneity and immediacy which underlie it. It may be that is the classic anthology of the 60s, even if it was published in 1987 and some of the poems were written after 1970.

Andrew Duncan’s book is, among other things, a series of advocacies of what Duncan calls ‘C*b*g*’ poets and others whose origins are in ‘the spontaneity and immediacy… of the 60s’, including Rosemary Tonks, J.H. Prynne, John James and Maggie O’Sullivan; but also a continuous, restless, reckless engagement with ‘the zone of thermal death’:

Conservatism is the dominant voice of the age, which is one of steadily rising property prices and ostentation. In poetry, the great fear of radicalism (a kind of taxpayers’ revolt against the destruction of chartered intellectual property) found an outlet in a mixture of infantile regression and stylistic regression, in which inane and artificially irresponsible tones were mixed with a conscious and discreet return to outdated forms fragrant of ‘old money’, to Auden, Betjeman, and Larkin… poetry seemed stuck in a Christian youth club of 1955, with teenagers sneaking puffs on fags and a guitar-playing ‘relevant’ vicar.

Not the least of the numerous ‘incidental delights’ discovered by Duncan in the course of his researches in the field is a deathless encomium of the mainstream by John Mole. Passing Judgements: Poetry in the Eighties consists of reviews for Encounter, aka ‘the CIA monthly’ (gag © Adrian Mitchell, Children of Albion) of 167 books. ‘If it appears that some well-known names are missing from the pieces gathered in this book it can be certain that they will have received their due elsewhere’. Let’s see, now… no, they all seem to be there. ‘I have often felt, and acted upon it, that if I don’t put in a word for the less fêted no one else will’. Well, one might have thought a poet named Mole an ideal guide to the Underground, but of the poets extolled in his pages, guess how many appear in A Various Art? Correct. His index lists the names of over 130. Blake Morrison appears twice, Andrew Motion three times and Anne Stevenson four times, but not a single poet associated with the Cambridge school, not even Roy Fisher. Mole’s self-professed taste is for ‘the slow ones’, whose writing is ‘unspectacular, modest, and traditional’; for poems which ‘sit four-square on the page, making pleasant conversation’ (i.e. the likes of Mole):

These poems are, generically, the well-weathered English stock, feet on the ground and head in the shivering allusions of those summer clouds. The risks they take are minimal, but their deceptive steadiness is so full of incidental delights of recognition that they often achieve considerably more than the awful daring of those moments of surrender which bring in the diminishing returns of febrile excitement.

I sympathise with the critic’s attachment to the ‘zoological English lyric’ (Peter Riley), but with friends like these, who needs predators? The qualification of ‘excitement’ by ‘febrile’ loads the dice, while the quotation from The Waste Land insinuates an obtuse antipathy to modernism that justifies Duncan’s contempt: ‘The risk these poltroons do take is that of being tossed on the fire if anyone with any sense comes across their books’.

There is plenty to dispute in this programmatically provocative book. Larkin is a blind spot (Duncan salvages a single phrase, ‘accoutred frowsty barn’); Donald Davie is seriously underestimated; Allen Fisher proportionately overestimated; excellent poets are given short shrift and weird choices indulged at length; the organisation is curious and the index a lottery. In my opinion, Duncan oversubscribes to Eric Mottram’s theory of the ‘British Poetry Revival’ (c 1959–60), despite his profound respect for the alternative theory ‘complete as stated in [Eric] Homberger’s classic work’, The Art of the Real, which sees the post-Movement landscape in terms of a more complex ‘Balkanisation’. He places undue credence in the derivative researches and dubious conclusions of Wolfgang Gortschacher; and (to put it mildly) oversimplifies the interrelationships between the 1960s and the two previous decades, or, for that matter, of the previous six, since he speaks in his introduction of ‘the failure of 20th C British poetry’, i.e. ‘the collapse on home grounds of pre-modern English poetry (say 1900–1960)’.

Nevertheless, for my money, The Failure of Conservatism is the finest critique of contemporary English poetry since Poetic Artifice by Veronica Forrest-Thomson (1978). In the comprehensiveness of its intention, it challenges the classic study, Thomas Hardy and British Poetry (1974), passing the point at which Davie gave up in exasperation, negotiating the disaster of Under Briggflatts (1989) and making previous assessments of our own period, such as those by David Kennedy (New Relations, 1996) and Sean O’Brien (The Deregulated Muse, 1998), look like the work of corporate hirelings. For all its distinction, even Neil Corcoran’s intelligent study, English Poetry Since 1940 (1993), is, in some important respects, all but indistinguishable from these miserable books.

2: ‘Publicity for Douglas’

Sean O’Brien offers his readers ‘a few words about what his book is and is not’:

It’s not a history or a comprehensive account of contemporary poetry in Britain and Ireland. That would be a life’s work and will need to be done by others at a later period, when some of the dust has settled…

The delegation and deferral of the genuine article is vintage O’Brien, but the idea that 300-odd pages on contemporary poetry could be anything other than the fruits of a writing-and-reading-lifetime-to-date is the real give-away here. The Deregulated Muse reads like this:

In the witty, severe, affectionate ‘Remembering Lunch’ [Douglas Dunn] pictures himself, a parody of the decent, staid Scottish dominie, walking energetically along the holiday shore, doing what comes ‘naturally’, only to be visited by an unanswerable enquiry:

Perhaps, after all, this not altogether satisfactory

Independence of mind and identity before larger notions

Is a better mess to be in, with a pocketful of bread and cheese,

My hipflask and the Poésie of Philippe Jaccotet,

Listening to the sea compose its urbane wilderness,

Although it is a cause for fear that only my footprints

Litter this deserted beach with signs of human approach,

Each squelch of leather on mud complaining, But where are you going?

It is no accident that the book taken along on the walk is Philippe Jacottet, or that the poem terminates in a tone (deadpan mock-heroic) and setting (empty shore with sentient objects) strongly reminiscent of a number of poems by Derek Mahon. Mahon is the dedicatee of Dunn’s poem ‘Realisms’, which employs the Irish poet’s patented triplet form, as well as the subject of an extremely appreciative essay which Dunn wrote in the late 1970s.

Severe? This must be one of the smuggest pieces of writing ever penned:

Noticing from what they talk about, and how they stand, or walk,

That my friends have lost the ability or inclination to wander

Along the shores of an estuary or sea in contented solitude,

Disturbs me on the increasingly tedious subject of myself.

The reader is presumably intended to disagree. Dunn mentions ‘serviceable footwear’ in line nine, then ‘the aforementioned impermeable footwear’ in line fifteen. I take it this is what O’Brien means by wit. As for Jacottet, his name is a simple substitute for Reverdy in ‘A Step Away from Them’ by Frank O’Hara:

It’s my lunch hour, so I go

for a walk… My heart is in my

pocket, it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.

Only Dunn could have made ‘Remembering Lunch’ out of Lunch Poems! And what’s all this about the ‘mess’ he was in? The simple answer to his ‘unanswerable enquiry’ is that he was well on his way to a Chair at St Andrews, where he surrounded himself with the likes of Robert Crawford, co-editor of Reading Douglas Dunn — and eponymous hero of Reading Robert Crawford by Douglas McMotion, Emeritus Professor of Golf. As it happens, this poem was one of the show-pieces of Morrison-Motion’s Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse (1982), a book I’ve loyally loathed for twenty years (ironic that it should be beautiful to behold: the cover, a Michael Andrews painting of the shadow of a balloon on a deserted beach, inside a white rectangular frame, deserves contents to match). ‘Remembering Lunch’ is exactly why. I refer the reader to the unexpurgated text.

If that’s where O’Brien’s at, what about Kennedy?

What makes ‘The Come-on’ such a complex and interesting poem and gives it a centrality in this chapter is that Dunn supplies, if I can so put it, the political dimension complacently glossed by Alvarez… The poem can in fact be read as a compressed version of some of the arguments Edward Said advances in his study Culture and Imperialism (1993)… Imperialism Said defines as ‘the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan centre ruling a distant territory’. It is this aspect of culture that the speaker of ‘The Come-on’ encounters when he asserts bitterly that the ‘enchanting, beloved texts… might just as well/ Not exist’… It is this that also prompts the question ‘Where, then, is “poetry”?’

Another no-brainer. ‘Poetry’, for Dunn, was to be found at the University of Hull, where he sucked up to Larkin, whose astute manipulation got him published by Faber. Or, if you prefer the tuppence-coloured version, his worth was finally recognised, even by the ‘dominating metropolitan centre’, to which he remained intransigently opposed. The traumatic years of bitter struggle as a radical librarian were over. He was twenty-seven (Selected Letters of Philip Larkin: 1940–1985, edited by Anthony Thwaite):

Born 1942 in Inchinnan, Renfrewshire. Educated at schools in Scotland and the Scottish School of Librarianship. He worked in libraries in Scotland and Ohio before taking a degree in English at the University of Hull (1966–69), after which he joined the staff of the Brynmor Jones Library, working there from 1969–1971. During this time, he was given a Gregory Award for poetry, and published his first book of poems, Terry Street (1969), with Faber & Faber.

One can only salute the political courage of this much-maligned firm in daring to publish such inflammatory anti-imperialism as ‘The Come-on’. How does it go again?

Brothers, they say we have no culture.

We are of the wrong world,

Our level is the popular, the media,

The sensational columns,

Unless we enter through a narrow gate

In a wall they have built

To join them in the ‘disinterested tradition’

Of tea, couplets dipped

In sherry and the decanted, portentous remark.

Therefore, we’ll deafen them

With the dull staccato of our typewriters.

‘Couplets dipped in sherry’ — pick that one out! Faced with the prospect of being typed dully to death by Dunn, you can’t blame Faber for capitulating. Larkin’s Letters contains a snap of himself, Dunn, Hughes and Richard Murphy, standing in what looks like a churchyard, after a shower. The ‘narrow gate’ to the big time is just out of the picture, but I bet the previous snap on the roll shows Dunn sneaking gleefully through it. On June 25th, 1969, Larkin sent two copies to Charles Monteith, ‘because I wondered if you could use one as publicity for Douglas’: ‘It seems to me the sort of picture that might be used to illustrate a chatty paragraph about Faber’s new poet about a couple of weeks before you publish his book’. Monteith obliged. On November 15th, Larkin asked Judy Egerton if she had seen ‘the Faber Quartet in Thursday’s Guardian’. In fact, he had a hand not only in the Gregory Award, but in Dunn’s appearance in Faber’s Poetry Introduction series:

You may be interested to know that the Eric Gregory Award Committee (on which I sit) is giving £400 to Douglas Dunn, who is a small muttering bearded Scotsman of 26 studying at this University… I believe Dunn has some poems in with you at present, though he mutters so that I can never be quite sure what he is saying. Would it be for some paperback series, or anthology, or something? I showed his submissions to Day-Lewis, too, and he liked them, or so he said.

I will book you in at the Station Hotel for the night of 2nd May.

So Monteith might have stayed in the very building that graces Duncan’s cover! No Award for guessing what the diminutive Dunn was muttering into his Scottish beard. At any rate, the obliging Monteith obliged again. In 1971, Larkin agreed to sponsor Dunn for an Arts Council grant (‘I’m your man’); and in 1972 acknowledges a return favour: ‘Ian sent me a copy of the Review… Your piece was very good, & very kind about me. May Heav’n reward you.’ Having found his ‘level’ amongst the likes of Ian Hamilton, Dunn has never looked back. Brothers, eat my dust!

It upset me to find Corcoran adopting the same obsequious procedure as Kennedy and O’Brien, and treating a passage of mind-numbing banality to admiring explication:

The title poem of Dunn’s fifth volume, St Kilda’s Parliament (1981), concludes with a very striking instance of… perceptual reciprocity… The poem is a fiction in which, from the perspective of the poem’s own present moment, the photographer meditates on the alternative and remote lives led by his nineteenth-century Hebridean subjects. After a career spent covering the political and cultural life of the intervening hundred years… this fantasy photographer has now returned to the unromanticised islanders of his 1879 photograph; and his subjects refuse subjection:

Here I whittle time, like a dry stick,

From sunrise to sunset, among the groans

And sighings of a tongue I cannot speak,

Outside a parliament, looking at them,

As they, too, must always look at me

Looking through my apparatus at them

Looking. Benevolent, or malign? But who,

At this late stage, could tell, or think it worth it?

For I was there, and am, and I forget.

… Raising the necessary moral question about all such appropriations — ‘Benevolent, or malign?’, ambiguously asked of both the islanders and the photographer — the poem gives this crucial preoccupation a memorable realisation; and it also suggests that even the best art intricates the artist, possibly despite himself, in the lives of those he uses.

How could such a bright critic have found this quintessence of dulness ‘unsettling but altogether compelling’? ‘Opaque but tantalising… with interpretative possibility’? Take away two random wrong answers, that leaves ‘Benevolent, or malign’… Can I phone a friend? Yet another ‘unanswerable enquiry’! But this one really is, because who cares?

On 3rd October, 1969, Larkin confided in Brian Cox:

We have a new Hull poet now, name of Douglas Dunn: his Terry Street has just come out from Faber’s, and I expect will get good reviews. Have you seen it? The Listener called him ‘the best poet since Seamus Heaney’, which is like saying the best Chancellor since Jim Callaghan. Anyway, to hell with poetry. I am fed up with it.

After reading more of Dunn today than ever before in a sheltered life, I know the feeling. One of the nightmare moments in Children of Albion features ‘Mal Caldwell, a learned hairy Scotsman’:

I am crazy for the feel of her wombanity…

My personal realities

against your politicalities,

cocks against the bomb…

Atrocity pictures, meester? You want

cunt with your curry?…

Just then Mal came in

drunk and learned…

‘The Vietnamese women are… ’

he raised his arm

in phallic appreciation…

Tumble off the bed, bellyful of curry,

tongue dry, arse heavy…

One would have to admit that Tom McGrath’s ‘Evidence’ is as objectionable as anything by the other ‘bearded Scotsman’, but I’d rather re-read Children of Albion, any day.

3: ‘Nature’s Swizzlesticks’

Corcoran and Duncan both include a highly selective year-by-year inventory of published poetry collections. Here are both lists for Corcoran’s last ten years:

|

|

||

The Flower Master |

Medh McGuckian |

The Poet Reclining |

Ken Smith |

The Hunt by Night |

Derek Mahon |

The Butchers of Hull |

Peter Didsbury |

Poems |

J.H. Prynne |

Poems |

J.H. Prynne |

The Goodbyes |

John Ash |

||

|

|

||

The Memory of War |

James Fenton |

Burning Brambles |

Roland Matthias |

The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Peguy |

Geoffrey Hill |

Roll Out the Corse |

Asa Benveniste |

Quoof |

Paul Muldoon |

River |

Ted Hughes |

The Liberty Tree |

Tom Paulin |

Berlin Return |

John James |

|

|

||

Station Island |

Seamus Heaney |

Mister Punch |

David Harsent |

Rich |

Craig Raine |

Azimuth |

Gavin Selerie |

C. |

Peter Reading |

A Bad Day for the Sung Dynasty |

Frank Kuppner |

|

|

||

Elegies |

Douglas Dunn |

All Where Each Is |

Andrew Crozier |

v. |

Tony Harrison |

The Branching Stairs |

John Ash |

Ukelele Music |

Peter Reading |

Dry Air |

Denise Riley |

Katerina Brac |

Christopher Reid |

Ranter |

Barry MacSweeney |

Writing Home |

Hugo Williams |

A Natural History... |

Maggie O’Sullivan |

Robin Hood in the Middle Ages |

Kelvin Corcoran |

||

Brixton Fractals; Unpolished Mirrors |

Allen Fisher |

||

|

|

||

A Furnace |

Roy Fisher |

A Furnace |

Roy Fisher |

Two Horse Wagon Going By |

Christopher Middleton |

Two Horse Wagon Going By |

Christopher Middleton |

Acrimony |

Michael Hofmann |

Continual Song |

Michael Haslam |

[Three Titles] |

Maggie O’Sullivan |

||

Proud Flesh |

John Wilkinson |

||

The Red and Yellow Book |

Kelvin Corcoran |

||

|

|

||

The Irish for No |

Ciaran Carson |

Selected Poems |

Peter Finch |

The Haw Lantern |

Seamus Heaney |

The Classical Farm |

Peter Didsbury |

Fivemiletown |

Tom Paulin |

Disbelief |

John Ash |

The Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper |

Blake Morrison |

The Intelligent Contemplation |

Frank Kuppner |

Eyes Own Ideas |

Colin Simms |

||

Filibustering in Samsara |

Tom Lowenstein |

||

Ingaitherins |

Alistair Mackie |

||

|

|

||

On Ballycastle Beach |

Medh McGuckian |

Qiryat Sepher |

Kelvin Corcoranc |

Tottering State |

Tom Raworth |

||

Unofficial Word |

Maggie O’Sullivan |

||

Themes on a Variation |

Edwin Morgan |

||

|

|

||

Zoom! |

Simon Armitage |

Wolfwatching |

Ted Hughes |

Manila Envelope |

James Fenton |

Stepping Out |

Allen Fisher |

Perduta Gente |

Peter Reading |

Trans |

David Chaloner |

From Berlin to Heaven |

Carol Rumens |

TCL |

Kelvin Corcoran |

Flesh Eggs and Scalp Metal |

Iain Sinclair |

||

Ridiculous!... |

Frank Kuppner |

||

Selected Writings |

Christopher Middleton |

||

|

|

||

Belfast Confetti |

Ciaran Carson |

Daylight Robbery |

Robert Sheppard |

Madoc — A Mystery |

Paul Muldoon |

The Mooncalf |

Alexander Hutchinson |

Collected Poems |

Edwin Morgan |

||

Sharawaggi |

Robert Crawford and W.N. Herbert |

||

|

|

||

Seeing Things |

Seamus Heaney |

Dreaming Flesh |

John James |

Love in a Life |

Andrew Motion |

Collected Poems |

D.M. Black |

HMS Glasshouse |

Sean O’Brien |

The Burnt Pages |

John Ash |

In the Echoey Tunnel |

Christopher Reid |

Dundee Doldrums |

W.N. Herbert |

Spectrum Shift |

Isobel Thrilling |

||

Firesong; Derivatives |

Tim Fletcher |

||

Stepping Space |

Ulli Freer |

||

The Bradford Count |

Ian Duhig |

||

Listening to the Stones |

Nicholas Johnson |

||

|

|

| ||

From the same ten-year period, Corcoran chooses 34 texts by 22 poets; Duncan 60 by 39 poets. Duncan’s mysterious exclusion of Northern Irish poetry ought to be noted at this point, since 12 of Corcoran’s texts and 6 of his poets are Northern Irish — as against a single solitary Scot. Yes, Douglas Dunn. Duncan’s challenging opening sentence (‘No modern British poet has an international reputation’) depends for credibility on the decision to subject ‘British’ poetry to ‘Ulsterectomy’ (© Andrew Waterman). Heaney, after all, won the Nobel Prize. It’s true that he objects to being called ‘British’, but he would, wouldn’t he? The greatest loss, in my opinion, is that of Michael Foley:

[L]et them sweep from the wide skies …

Urge the dads to move up

from Scale Three to Four…

In thousands over the frozen fields

bring his duty home to man

O funereal bird.

Spur the insensitive up the scale

and come home to roost in the trees

in the magical dusk.

Save the warblers of May for the truly down

lost in the nightmare brambles

facing defeat without redress.

(‘The Crows’)

Thankfully, Duncan shows no further interest in this ‘Superleague’ (a concept attributed by Kennedy to Blake Morrison), which consists chiefly of names such as Brodsky and Walcott — but, for what it’s worth, it looks as though Prynne is on the verge of promotion.

Even discounting the Irish, it is amazing that the total overlap between these lists should consist of no more than three books: Poems (1982) by Prynne; A Furnace by Fisher; and Two Horse Wagon Going By by Middleton. What Corcoran unwittingly supplies is an itinerary for ‘the domain of absolute artistic corruption’: the mainstream of the 1980s, as viewed by Duncan. Rightly, in my opinion. How many of us, I wonder, consider Blake Morrison’s Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper to be ‘a subtle poetic contribution to a developing politics of sexuality’, as Corcoran does? Here is his account of the Martians:

What am I? A telephone, the reader answers, but only after a pause… The routinely functional, the virtually invisible, has become a partner in relationship; the object has, as it were, become a subject, animated into a newly destabilised oddness and accuracy… This perceptual revision, usually heavily dependent on an exuberant use of visual simile and metaphor, is the essence of the Martian style, and it has led some critics to align it with that process of ‘defamiliarisation’ theorised by the Russian formalists of the 1920s, Shklovsky in particular… One of the finest examples in Christopher Reid comes at the end of ‘Baldanders’…

Glazed, like a mantelpiece frog,

he strains to become

the World Champion (somebody, answer it!)

Human Telephone.

The weightlifter crouched to his weights is shaped something like a frog and a telephone, and he gleams with sweat and oil, as pottery gleams with its glaze; and the wit of these lines is partly dependent on this perception of physical relationship, a perception itself dependent on a sharpened and refined visual, tactile and spatial sense. It depends also, however, on the exasperated, almost demented demand of the parenthesis, which, with a brio of compaction, relates the effortful, straining desperation of the weightlifter to the ordinary strains and exasperations of domestic or office life, and registers with a kind of affectionate, uncondescending amusement the entertaining absurdity of the endeavour: who would put himself through such hell to be a champion telephone; but, equally, who would not admire the spectacle?

Is Reid’s gag any funnier by the time Corcoran has finished with it? Such as it is, the joke is surely on this ‘effortful’ prose. ‘[W]ho would not admire the spectacle?’ Reid, for one. Far from being ‘uncondescending’, the poem strikes me as a sustained sneer: ‘Pity the poor weightlifter… His Japanese muscularity/ resolves to domestic parody’. Surely this ‘parody’ has more to do with the ‘effortful straining’ of constipation than with ‘the exasperations of… office life’? The smart ‘parody’ of ‘Pity the poor immigrant’ is all of a piece with the light-hearted xenophobia, epitomised by the epigraph to ‘Utopian Farming’: ‘Every nation is to be considered advisedly, and not to provoke them by any disdain, laughing, contempt or suchlike, but to use them with prudent circumspection, with all gentleness and courtesy’ (Sebastian Cabot). Reid’s art is a supercilious charade, a ‘white pretext/ for a solemn Tudor dance’ (‘A Parable of Geometric Progression’). Despite Corcoran’s flattering offer of ‘perceptual revision’ as its raison d’être, Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings is more to the point than Shklovsky:

Baldanders (whose name we may translate as Soon-another or At-any-moment-something-else)… is a successive monster, a monster in time. The title page of the first edition of Grimmelshausen’s novel takes up the joke. It bears an engraving of a creature having a satyr’s head, a human torso, the unfolded wings of a bird, and the tail of a fish, and which, with a goat’s leg and vulture’s claws, tramples on a heap of masks that stand for the succession of shapes he has taken.

Reid, in turn, ‘takes up the joke’, with a teasing cryptogram of his own grotesque style. I’d never heard of ‘Baldanders’, in fact I thought it might be a typo for ‘Badlanders’. Reid’s ideal reader wouldn’t have the faintest idea either, but would dutifully look it up, then chuckle appreciatively. ‘Everything that we see … is ours to make use of:/ palm-trees on the marine drive,/ nature’s swizzlesticks’… NATURE’S SWIZZLESTICKS??? This is enough to bring on an attack of style-rage, which is like road-rage, only nastier. In 1982, this was where it was at. You had to be there.

4: ‘The Neo-Movement’

One of my souvenirs is British Poets: A Special Issue of Poetry (Chicago), guest-edited by Elise Paschen (Vol. 146 No. 4, July 1985), actually a Martian Special Issue, with a supporting cast of Penguin Contemporary Poets, and an essay entitled ‘Contemporary British Poetry: A Romantic Persistence’ by John Bayley:

Not long after the war a new movement in poetry began… These poets did not seek to be anything in particular, and none of their claims are very positive. They repudiated Yeatsian grandeurs, Auden’s tendency to cut capers and show off… Drunken genius, like that of Dylan Thomas, was to be at all costs avoided… Nonetheless, where Larkin was concerned, Romanticism crept in by the back door… Larkinian ‘otherness’ is a significant ingredient in later British poetry… This is true even of the poetry associated with Craig Raine, whose practitioners are sometimes known as the ‘Martian School’. Such poetry involves a process of ‘making it strange’ (the title of a recent poem by Seamus Heaney), a technique ultimately to be identified with the Russian formalists… Douglas Dunn, the most accomplished of the poets who have learnt from Hardy and Larkin, shows the same gift, especially in his ‘Terry Street’ poems…

So there you have it: Hardy > Larkin > Heaney > Raine and Dunn. My favourite bit is where Bayley compares the Martians to Shakespeare and Ben Jonson ‘in the Mermaid tavern’, citing David Sweetman’s ‘sandworms’ and Raine kissing his telephone to sleep.

The first poem is John Fuller’s ‘The Curable Romantic’, who ‘pedalled vigorously/ Hunched at a snail’s pace// Towards the dead familiar/ Landscape of his life// As he certainly will again/ Tonight, and every night’. Bring back the drunken genius of Larkin! An even more obviously blighted poem is duly entitled ‘Bud’: ‘A strange remission/ From cycles of that long disease/ Which every estimate agrees/ Is our condition’. Echoes of Auden’s elegy for Yeats (‘O, all our instruments agree… ’) and Pope on ‘this long disease, my life’ are mangled into the astonishing assertion, not only that Fuller sees life as essentially a long disease, but that that there’s no argument about it! Yeats, after all, was dead; and Pope had contracted a spinal disease at the age of seventeen. It was one of the characteristics of the Movement to claim the right to speak on behalf of us all (‘Life is first boredom, then fear’), but, granted or not, was it ever more pathetically abused?

Here is Duncan’s account of the same phenomenon:

The atmosphere which, in the 1950s, restricted the scope of poetry to almost nothing, was still predominant in the 1980s. The ‘ludic’ poem, which we can interpret as the offspring of the ‘funny’ poems in New Lines, achieved a fickle popularity. In someone like Craig Raine, erudition was a reductive collusive signal of class status (‘we’re both educated people’), the jokiness was an attempt after the excesses of the experimental Seventies to appease the imagined audience… Trivial games were seized on to prove that these poets were not interested in issues, and so innocent. In the work of James Fenton this superciliousness supplied good poetry, if only for a few seconds.

Duncan’s originality is in the grudging appreciation, both valid and validating, of Fenton’s intermittent excellence:

The nineteen pages of ‘Exempla’ (probably 1968–70) seize material from the outside world, typically from a museum, which is deliberately irrelevant to the poet. This resembles the documentary preoccupation of conceptual art, but lacks all political value; he is amused but no more. He fights against the surplus of meaning in the human world. Other people integrate the elements of the world supplied by their senses to make a synthesis, an integrated sensibility which generates its own meanings and is the overall subject hidden and revealed behind the poems; Fenton exhibits only a dissociation of sensibility. His poetry is observed by an eye with nothing behind it; like a camera… His refusal of mental acts higher than bare perception is lockean. He describes how a frog’s eye can only detect movement, and does not move separately from the body; an equation of awareness with the mechanical limits of the perceptual system as a data-gathering device which points towards phenomenology and the critique of human awareness and perception; but Fenton seems blithely unaware of any analogy, refuses to make any models for hypothesizing, closes off the chains of possibilities by neat metrics…

The poem about the anthropological exhibits in ‘The Pitt-Rivers Museum’ does not associate the artefacts with their source societies, does not look through the objects to imagine alien mentalities and geographies, does not walk outside the banalities of an afternoon in a museum in an English city; we seem to have found a poet who lacks imagination altogether, and this is perhaps a more remarkable exhibit than a head-dress made of feathers… His best poetry is in The Memory of War, specially in the sequence ‘A German Requiem’ (published 1981).

The Martians were the heart and soul of Morrison-Motion, together with the likes of Tony Harrison (‘Their snaptins kept amongst their turds/ they labour eat and shit/ with only grunts not proper words/ raw material for t’poet’), a couple of good Northern Irish poets and several duff ones. Wait a minute… ‘Their snaptins kept amongst their turds’? What a thing to say! O’Brien bemoans the lack of criticism by ‘the people you might care to hear from, such as Tony Harrison or… Douglas Dunn’, and entitles his chapter on Tom Paulin ‘The Critic Who Is Truly a Critic’. It would be wrong to number Paulin amongst the Irish duffers, since he is, after all, as Irish as my arse — come to think of it, my arse is, in fact, Irish, so let’s say ‘as Irish as Duncan’, since both were born in Leeds. Not that it would matter a clabbery boke where the choggy wazzock had been born, if it weren’t for that insufferable stage-Irish.

With explicit reference to ‘the neo-Movement’, Duncan develops the classic account by Andrew Crozier (‘Thrills and frills’, 1983), in which Martianism is identified as one of a series of minor modifications by which the ‘hegemony’ of the Movement has been renewed:

As the progeny of Larkin and Roger McGough merged, it became easier to see those two writers as merely successive waves of anti-literary, desensitised, restricted-vocabulary, populism… The 1970s have now emerged as the classic period of modern British poetry: when the breakthrough paid off in finished poems rather than wild glimpses of an imaginary freedom, before the hangover set in, before the growth of the media made slickness and inauthenticity universal. This revolutionary-classic era was the fallout from the explosion of 1968… A radical expansion of the sensory possibilities open to the imagination blew up the boundaries of poetry… The initial velocity was very great, and as each poet travelled a great way they became distant from each other, as well as far from their point of origin. In this post-explosive geography, almost all publicised poetry belongs to a tiny dull mainstream, and almost all serious poetry is uncelebrated.

In the most balanced account to date, the infamous ‘squabble’ over Poetry Review in 1977 is mapped onto this topography:

From 1971 Eric Mottram, a lecturer at King’s College, London, edited the Poetry Review, owned by the Society, and published largely English modernist poetry… In March, 1977, the 14 modernist members of the Council all resigned, in protest against the Arts Council’s pressure on them. Subsequently Mottram’s contract as editor expired…

Duncan acknowledges ‘the corruptness of several of the dashing rebels’:

The Arts Council never admitted to artistic reasons for purging the Council, but only to misgivings about pumping public money into an organisation whose business management was so shaky. Of this they had all the evidence they needed… There is a persistent story about two… Council members boasting about stealing all the valuable books from the Society’s library, which relied on trust…

He is sharp on the more exasperating aspects of the modernist wing:

The conservative coup induced the modernist poets to implode, both in style and in business… the ‘London scene’ sulkily responded by years of appallingly produced, sub-medieval home-made books. This alienated the public and booksellers for a decade… The psychological state of an artist who never expects the audience to arrive is complex; of course it selects for fanaticism, as the softer members bale out and find success elsewhere… Paranoia… drags with it pitiful loyalty to marginal, foreign, or imaginary authorities, outlaw Popes without artistic attainments except intransigence.

But the effect of these home-truths is to reinforce the impact of his conclusion, in which modernism is personified by Mottram and the zone of thermal death by Motion:

British poetry would have been a whole lot better over the past 15 years if Mottram had remained as editor of Poetry Review… There is a horrible difference between the magazine he edited and the version — bright, bouncy, but without intelligence — which followed in the Eighties… There is a direct link between the policies of the ‘moderate’ group in 1976 and the editorship of Andrew Motion at the Poetry Review (1982-3), which set the agenda for a great deal of the Eighties… Motion’s poetry was the calculated image of mediocrity and reason… This tactic of ‘mediocrity as fitness for power’ was to be exploited with ever increasing success for the next 15 years…

5: ‘The Pleistocene is Our Current Sense’

The three poets common to both Corcoran’s and Duncan’s lists — Fisher, Middleton and Prynne — have a chapter to themselves in English Poetry Since 1940, in which Corcoran’s method — deal with all the current names, say the best that can be said, express a few reservations — earns more respect. I ought in fairness to have quoted his reservations about the Martians, though they don’t redeem that ignominious chapter. Amazingly, neither Kennedy nor O’Brien makes any reference whatsoever to Prynne. He doesn’t even make the index of either book (I’ve just double-checked). By contrast, Corcoran’s comparison of ‘The Glacial Question, Unsolved’ to the poetry of David Jones (‘although as far as I am aware… the connection has not been made’) is excellent. I wonder why he didn’t substantiate his argument by quotation, which he might easily have done:

… The

moraine runs axial to the Finchley road

including hippopotamus…

And the curving spine of the cretaceous

ridge, masked as it is by the drift, is

wedged up to the thrust: the ice fronting

the earlier marine…

Our climate is maritime, and

“it is questionable whether there has yet been

sufficient change in the marine faunas

to justify a claim that

the Pleistocene epoch itself

has come to an end.” We live in that

question, it is a condition of fact: as we

move it adjusts the horizon: belts of forest,

the Chilterns, up into the Wolds of Yorkshire…

We know this, we are what it leaves:

the Pleistocene is our current sense, and

what in sentiment we are, we

are, the coast, a line or sequence, the

cut back down, to the shore.

References

W.B.R. King, ‘The Pleistocene Epoch in England’, Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc., CXI (1955), 187-208.

[‘The Glacial Question, Unsolved’]

Compare The Anathemata:

Before they morained Tal-y-llyn, cirqued a high hollow for

Idwal, brimmed a deep dark basin for Peris the Hinge and for

old Paternus.

‘Contemporaneous with the glaciers of North Wales, ice sheets from the Clyde Valley and the Southern Uplands of Scotland, from the Lake District and from the heights of north-eastern Ireland descended and converged into the depression of the Irish Sea. From this area of congestion the combined flows moved southward under great pressure, part escaping directly by way of St George’s Channel, but part thrust against the land mass of North Wales.’ Bernard Smith and T. Neville George in Brit. Reg. Geol. N. Wales, pp77-78.

Through all orogeny:

group, system, series, zone.

Brighting at the five life-layers

Species, species, genera, families, order…

Lighting the Cretaceous and the Trias…

Through the slow sedimentations laid by his patient creature

of water…

Through all the metamorphs or whatever the pseudomorphoses.

As, down among the palaeo-zoe

he brights his ichthyic sign…

Brighter yet over the mammal’d Pliocene…

Brighting totally

the post-Pliocene

both Pleistocene and Recent.

In addition to a startling series of technical and lexical similarities, Jones’s argument for the origin of Christian light ‘among the palaeo-zoe’, and its steady intensification throughout the evolutionary epochs of prehistory, is remarkably compatible with Prynne’s insistence that ‘the Pleistocene is our current sense, and/ what in sentiment we are’, on the grounds of continuity in ‘the marine faunas’ during ‘post-Pliocene’ times.

Corcoran has written a study of The Anathemata (The Song of Deeds, 1982), which ought to be worth reading. As for Seamus Heaney, though, I think I’ll pass (Faber, 1986). I recall a review by Tim Kendall, attacking an ‘unnecessary’ academic book. Kendall then proceeded to write Paul Muldoon (Seren, 1996). One deduces that a guide to a smart standard-issue Faber poet, canonical since 1982, is his idea of a necessary book.

My idea of a necessary book is Duncan’s. This is criticism for his own newly-identified sociological category of ‘intelligent and thrill-seeking persons’, if I’m any sample:

The White Stones by J.H. Prynne (b.1936) is probably the most significant single volume of the 1960s. Prynne sums up the span of the decade, with a poetic facies which seems like a roll-out of instrumental and mathematical knowledge, and simultaneously could come from inside the shimmering, hyperassociative, helical logic of an acid trip.

I feel that Prynne’s dominant theme is his resistance to political idealism. His most positive affect is rage against examples of idealism — located in various forms, e.g. heroism, polarisation, moralistic division into Good and Evil, craving for quick solutions, simplification of the facts to supply stories with heroes and happy endings. I say ‘anti-idealistic’ because I find this scepticism and scorn one-sided; it is very scorching and verbally impressive, but it lacks dialectic. The difficulty with forming symbols is close to a generalised depression; it seems to me that happiness and normal functioning is impossible unless one has hope, love, trust, and ambitions, all of which involve idealism of some kind.

Prynne, although a poet of the Sixties, is decidedly un-Sixties in working inside an implied moral schema, rather than a hedonistic one; the hedonism, personal and intellectual, of other people, is grist to his mill, and is fitted into a grid which mercilessly reveals its errors and anisotropies. The hypothesis is that Prynne is really a continuator of the limit-obsessed poets of the 1950s, when what passed for political astuteness was scepticism and careful textual analysis…

The sceptical absence of ideas and ideals was also the Movement’s formula; Prynne and Davie were friends as postgraduates at Caius in the late 1950s. The cult of Prynne, already a presence in 1966, is due to his uncannily fine sense of divisions of time and tone, and his ruthless purging of micro-gestures, or subsyllabic weights, which offend that microscopic, impassioned, quivering instrument. If the difference between Geoffrey Hill and his contemporary Adrian Mitchell is Hill’s far superior refinement, the same gap of delicacy and eschewing of effect again separates Prynne from Hill. His moral disgust at the gross processes pulsing around him took the form of Marxism. Prynne studied at Caius after National Service (which, for some inexplicable reason, was with a Polish tank regiment. When I mentioned T-34s in a poem, I was startled to find Jeremy reminiscing about what they felt like to drive in…)…

The anecdote about the T-34 Soviet tank is priceless. The metaphors of ‘facies’ (the appearance and characteristics of a rock, usually reflecting the conditions of its origin) and ‘anisotropies’ (the variation in a crystal of physical properties observed in different directions), beautiful in their precision, are drawn from one of Prynne’s own image-complexes, yet the critic also stands outside the enterprise to express some remarkable reservations. The hypothesis ‘that Prynne is really a continuator of the limit-obsessed poets of the 1950s’ is not only valid, as Steve Clark has argued (Jacket No. 24), but contains enough explosive to detonate one of the principal arguments of the book, according to which 1959 is the point of departure for the British Poetry Revival. For my own take on Duncan’s argument, may I refer readers of Jacket to the (forthcoming) second instalment of ‘Schönheit Apocalyptica’. You can read the first instalment in Jacket 24.