Forrest Gander and Kent Johnson

Ni Pena ni Miedo:

A Sentimental Education in Chile

Notes are given at the end of this file, with links that look like this: [71]. Click on the link to be taken to the note; likewise to return to the text.

Preamble: The following travel notes [1] by Forrest Gander and Kent Johnson were written during and after a three-week journey to Chile in October of 2005. They were composed in a call and response spirit, the serial result approaching, one could say, a blend of renga, haibun, and poetry-cartoon bubbles. If its notational texture seems closer to waking dream than level-headed reportage, then perhaps we have found a form adequate to the experience we enjoyed.

As the travelogue recounts, we departed for Chile at separate times, meeting up in Andacollo, in the northern part of the country. This was the location of Festival de Poesía Cerros de Oro de Andacollo, the first of two poetry festivals to which we had been invited. We then made our way south. The second festival was the larger Chile-Poesía, held in Santiago.

Forrest Gander:

I, F, have misread the invitation. It does not say Join us for the Festival of Cerdos de Oro, pigs of gold, but for the Festival of Cerros de Oro, hills of gold.

Kent Johnson:

And I, K, misimagine it: a colonial town, elegantly dissipated and pasteled, ringed by forested foothills, trout streams in the ravines, the baroque-era gold mines half collapsed and forgotten.

Forrest Gander:

Heading to Chile tomorrow to fall together with some poets, I email Tony Frazer, editor of Shearsman Books, one of the best literary presses in the U.K. He replies, I recommend Santa Rita Cabernet Sauvignon (the Reserva), Los Vascos (just about anything with that label), Errazuriz Panquehue’s Cabernet labeled, if I remember right, Don Maximiano (the white was Doña Leonor) and the Gran Tarapaca Cabernet.

And how do you get to Andacollo, Chile? You fly all day to Santiago and when you land, you take another flight 500 kilometers straight up the coast to La Serena. Built by the Indian-killer Francisco de Aguirre in 1549 (just ten years before even more notorious Lope de Aguirre launched his ill-fated expedition for El Dorado), La Serena is a handsome, neo-colonial town of churches and convents. Your regular taxi takes you from the airport through streets flanked with white houses to the corner of Calle Domeiko and Avenida Francisco where you get out and wait, slumped on the curb across from a muffler repair shop, until a collective taxi driver — this is his corner-- can rustle up two more passengers for Andacollo.

It’s a tight squeeze and a long ride through cactus plains and semi-desert mountain roads from which we can sometimes glimpse the snowcapped Andes. At last we descend into a gorge with a town flung into the bottom of it. (The only corollary in my experience is the brake-smoking arrival into the paranormal abyss of Guanajuato, Mexico).

Road to Andacollo

Kent Johnson:

Having arrived to Santiago ten days before F, I make my way up the spectacular coast via bus, stopping in seaside towns. Astonishing Valparaíso, to which F. and I will return; Coquimbo, with its handsome plaza, overseen by huge relief sculptures of Neruda and Mistral; before the latter, Vilos: windswept, scruffy place, where I stay up until 5 a.m. in a bar on the rocky beach, drinking with half a dozen mollusk divers, who are deeply impressed by the fact that I am an American poet on my way to an international conference in the birthplace of Gabriela Mistral. Two of them recite, from stumbling memory, five or six Chilean verses, some by 19th century Modernistas I’ve never heard of — great theatricality as they do so, hands held out or over hearts, tears and applause, bottles and shells of crab and sea urchins all over the table and floor, curses for the current neo-liberal “Socialist” regime of Lagos, which enforces a law that only permits them to dive in their home “region”; hurrahs to the glorious name of Salvador Allende, “True Socialist”; long tales of great adventure and danger that take place underwater, battles with giant octopi, and so forth…

And before Vilos, tiny Horcón, where the colored boats are pulled into shore by horses at low tide, where I meet Francisco, a fisherman in his late twenties, magnetic, with movie-star looks. We talk in the café on the beach for a long time, and everyone seems to go out of their way to greet him, especially the women; he’s clearly the man in town. I learn he plays the electric violin. He makes extra money that way in the tourist season. “Jean-Luc Ponty is my hero, a very advanced artist,” he says. “And out there, ten kilometers off the other side of that point, I almost died a few weeks ago, when the biggest storm of the year caught us by surprise.” Later I wander into the Restaurante Museo Horcón, two floors of curios and bizarre antiques everywhere. I meet the owner, Victor Suarez Johansen. He turns out to be one of the great collectors of Chile. His restaurant in Valparaíso is called Casino Social JJ Cruz and is more packed with artifacts than this one. He’s a small and intense man. He holds a little dog and wears a red sweater and green pants. “I own manuscripts by Neruda and the poncho he wore in Temuco when they celebrated his Nobel. I have many, many things. To collect is my life.” He gives me his card and tells me to call him when I go back to Valparaíso in ten days or so, as he expects to be there. He wants me and F to come to his house.

Prayer Wall

When the taxi lets us out at the Church of The Virgin Rosario of Andacollo, I meet K, the other poet from the U.S. We are magnetized to the wall of prayer plaques perimeterizing the church. Made of marble and iron and sandstone, they’re shaped like hearts, shields, and open books. Hundreds of Thanks to the Virgin “por haber escuchado mis oraciones” — for having heard my prayers, “por salvar nuestro hijo” — for saving our child, “por el milagro concedido” — for the granted miracle. In an unusually specific retablo, a mother thanks the Virgin for helping her daughter turn from the demon of drugs. In another, the only one in English, Miriam, who trekked to Andacollo from Australia, offers plaintively: “Thanks for Forgive My Fault.”

And this one, which we both regard, quietly, for some moments: “Thank you, Compassionate Virgin, for giving us back our son.”

Andacollo

Andacollo Home

The bordering river is dry, a depository of bulging green plastic trash bags and strewn litter. Andacollo, like Juan Rulfo’s mythic Paramo, is haunted by the ghosts of miners and dusted with tailings that blow steadily from the denuded, buzz-cut, and beveled mountains, one behind the other into the horizon. An apocalyptic landscape with micro-avalanches of dark sand pouring in slow motion down sun-baked hills. In the cratered flats, black, orange-fringed pools glisten like tar pits.

Evaporation Pit

Even within the town, mere blocks from the city center, there are numerous, towering mounds of a yellowish-brown cake, pocked with burrows — wastage from the 19th century or before, the policeman tells me. And the holes? People dig and crawl in, every so often, hoping to find something the first ones missed.

A hatbox of a room. A pocket of a room. Our room for the week is no bigger than a pickup truck. I sleep with my suitcase on the bed with me. Two feet away, K snores like Unferth. [2] Waking at 4 a.m., I step out to the street to check the stars and a man bicycles past me. He is on his way, I will be told later, to the gold mine to break stones all day. At dark, he will bicycle home again. Month after month, for a few dollars a week….

Listen. The three thousand dog nights of Andacollo.

In Chile, the dogs are quasi-citizens, beloved. They roam wild, bother no one, doze on the sidewalks, heedless of the passerby. I have seen the dogs of Chile look both ways before crossing the street. At ease in their skins, as they say. But at night they howl, as if in terror, and who knows why.

When I sit across from one of the local poets at dinner, she turns away because I’m from the U.S. Although there is no one else close enough to engage in conversation, she lights up a Derby cigarette and sullenly blows smoke, looking down the table.

Andrés Ajens, poet extraordinaire, close collaborator in “translucination” with the Canadian poet Erin Mouré: terrifically funny, wired, he stutters, waves his hands in flustered pauses, unleashes a cascade of seamless brilliance. It is his style. Everyone loves him, not least us.

Andrés Ajens

Between three shopkeepers, an accord is reached regarding the best wine in the shop and the bottle I should buy.

The one that is four times as expensive as any of the other bottles in the shop.

Walking beside his young wife, he tries to steer, with a menacing glare, the eyes of passing men from the perk of her breasts.

National elections loom. Outside the offices of the local branch of the Communist Party, we help push a pick-up truck to get it started. It revs up, to hurrahs and backfiring and oily exhaust, and proceeds at jerks down the cobblestones, loudspeakers blaring a scratchy Victor Jarra classic. It moves off, toward the cathedral, red flag with the hammer and sickle at full wave. “Gracias camaradas estadounidenses!” the young driver shouts back to us. We stand there in a bluish haze.

One afternoon, between poetry panels, K and I enter the Church of The Virgin Rosario of Andacollo to pay our respects. Upstairs, in the antechamber to the Virgin’s room, we encounter display cases of offerings from various countries. Samurai armor. Spoons. A red robe from a church in Kenya. The Chinese banners praise, so say instructive notecards, the Virgin of Andacollo.

In the cathedral’s outer courtyard, where the prayer plaques are, we’d chatted with an elderly man and a young woman, as they peeled back, with hoes, a fleshy muck from the stones: monthly strata of votive candle wax. Now our sticky shoes make little lip-smacking sounds inside this treasure chamber of alogical gifts.

The last daylight spiders down from a small ring of stained glass in the ceiling. According to legend, a peasant found a wooden statue of the Virgin in Brazil and lugged it back to Andacollo where it became known for the miracles it bestowed on the faithful.

He found her, it’s told, in a firewood pile, deep under branches and stumps, fully gowned in her white and gold, crowned and bejeweled. Why, we wonder later, deep into beers, would she choose to appear from a heap of timber? “Why not?” shrugs the dark-skinned waiter, smartly snapping off the tops from two half-liters.

The Virgin of Andacollo stands about three feet high. Her white, silken, perfectly isosceles gown, strung with loops of amethyst, covers her from neck to feet. The short brown hair on her wooden head is topped with a gold crown. From her ears, slightly outturned, two leaf-shaped earrings dangle. One of her brown eyes looks sleepy and the other focuses intently downward.

The Virgin of Andacollo

But all we can see when we enter the upstairs chapel is her back. Behind a wrought-iron grate, she stands on a small platform looking down into the nave of the church a floor below us. When we press ourselves to the grate, we share her perspective of the empty pews, but her countenance remains invisible to us. Then, just before we leave, we notice a dark rope tied to one rail. Its other end seems to attach, like a crude umbilical cord, below the skirt of the Virgin. I kneel and tug the rope and slowly, without creaking, the Virgin turns around to face us.

Not since that night in La Paz, when Gisela slowly lifted the scarf from her uncle Jaime Saenz’s death mask, have I felt a more intense desire to run.

When fog covers the town, says the barkeep, it is understood that someone is about to die.

Cigarette butts around the bare twig in the sand of the flower pot.

We don’t know it yet, but in two days, rocketing down the road in our taxi colectivo toward La Serena, tires squealing around the hairpin turns, the whole mountain will be covered in a spectral fog. A small picture of the solemn, doll-like face of the Virgin of Andacollo will dangle and dance from the rearview mirror.

And what are those things that look like white stupas on the hills around Andacollo, we ask him. He hints that he has a story to tell, that it involves a cult of Tibetan monks, but we don’t return the next day, as we promise, for the revelation.

When I’d first arrived into town, the driver, pointing out the establishment, had told me about him: “He runs the best place to eat and drink in all the town. But just so you know, he’s famous as a llorón.”

“A llorón?”

“Yes, he’ll be telling you about something, and then for no reason at all, he’ll start crying like a baby. But almost all the towns in these hills have their llorón. It’s a feature of the area.”

Even were they in English, and perhaps more so, I would find these long conversations exhausting. Nervous, I bluff fluency with a convincing accent and speedy sentences which lead to stupid grammatical mistakes that, like the gambler’s martingale, re-double my nervousness and compensatory speed, leading to more goofs, clumsy pauses and overwhelming disappointment. I feel myself falling in slow motion — like James Stewart in Vertigo — into a well of silence below the world of human voices.

Or as they say in Andacollo: “The poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection to the axis of combination.”

One night we take a bus to La Silla (The Saddle), one of the famous observatories bordering the southern extremity of the Atacama Desert. After a tour of the facilities, we trundle out into the high, cold, desert night to look at a constellation named for a parrot. When my turn comes to cup my eye to the lens, I can make out only two little points of light. There are cuernos de cabra in bloom around the observatory, and the air is so still I can smell the nighttime sweetness. A low hum of conversations is all the harder to track because I can’t see anyone’s lips shaping the words. Shivering, I go inside with the others to the auditorium where our hosts have planned an evening of readings by twenty poets. The first to read decides it would be unfair to skip any section of his book-length poem based on Melville’s Ishmael and so, already drunk on free pisco sours in the lobby, he throws his serape over his shoulder and declaims for a solid hour and twenty minutes. It’s a little after midnight. Nineteen poets to go.

Guermo Daghero

Late the next night with Andres Ajens, Guillermo Daghero, and F, Ajens turns to me precipitously and, bird hands aflutter, asks, “And you, my dear Sir of the North, what do you hope to accomplish in your life?”

“Well, I’ve already accomplished quite a lot, don’t you know,” I say, feeling a surge of pisco- sour cleverness coming on. “I am, for one, the most famous poet of Stephenson County, Illinois, USA!”

There is a pause.

“In Chile,” adds Ajens. “The most famous poet of Stephenson County, Illinois, USA in Chile.”

Toward the end of the third day of the festival, after many papers, a consensus emerges that there are no longer regions of poetry, but there are zones. Tarkovsky is mentioned. In his own talk, K critiques the presumptions of urban vanguard poetry in relation to rural and regional practices.

On the final night, a Mexican poet aggressively accuses the organizer of avoiding the issue of regionality altogether, of talking around it with language games when, in fact, some people’s lives were at risk because of their writing’s relation to the place where they live. Another poet shouts that vanguard poetry doesn’t speak to him at all, that it is elitist, that the tone of the whole conference is elitist. And so the last evening dissolves in tensions, wounded feelings, a dinner table balanced like a barbell, with partisan drinkers clustered around either end.

Things had started better: the big assembly of students that greeted us; the blind disc jockey who recited Mistral and sang our welcome a capella; the opening banquet of high spirits and fine local fare; the attentiveness and kindnesses of the organizers. And the unforgettable poets: the dervish performances of Reinaldo Jimenez, brilliant editor of Tsé-Tsé; the young Román Antropolsky, fan of Zukofsky, his reading a torrent, the syntax dissolving, making a strange total sound; the distant Guillermo Daghero, his “object poems,” with open spaces, tables, statues, sheep, even the cow of Jacques Roubaud; the intense Susy Delgado, telling of Guaraní literature, of poetry codexes, lost books of bark, hidden away in forests and small towns; the enigmatic macaronics of the Mapuche poet Graciela Huinao; the echoing architextures of Silvia Guerra; the critical eloquence of Marcelo Novoa; the Saenz-inspired visions of Jorge Campero and Juan Carlos Orihuela; the wild humor and stunning capacities for drink of Antonio Gil and Miguel Coletti… Ajens beaming, gesticulating wildly, holding everyone together.

I am rendido, rent by the effort of constant attentiveness to even the most casual conversation with someone who, were language more exchangeable, might be a friend.

The gift of books cannot be refused, although there is no space for them in our suitcases. Arigato-meiwaku. That’s what Basho said as he hiked around Japan accumulating gifts he could not carry. Thanks, but no thanks.

Basho or no, the books begin to pile up. Japanese businessmen offer business cards; Latin American poets offer poetry books.

When the large companies pulled out, some local miners stayed and continued to dig for whatever might have been left behind. Then they too thinned out. The town began to crumble. The exodus began. This small mining operation — four or five men-- must have been failing too and so the owner, his gums mottled and brown, flecks of saliva at the corner of his mouth — a sign of mercury poisoning — is glad to show us, his tipping Orphean visitors, around. In the severe afternoon sun, one man is crushing stone, another scooping the pieces into a crude wooden sieve. The owner leads us below the tin roof where sieved gravel is swirled into large washtubs. Here he takes a vial and pours into his hand several beads of mercury which roll like marbles across the grooved life-lines of his palm. He smears the mercury against a tin plate that he inserts into a rack at the side of the washtub. After he swishes the muddy water with a paddle and takes out the metal plate, we see the patina of gold adhering to it. This he wipes into a cloth filter, again with his bare hand.

Sifter at Gold Mine

Then he uncaps a bottle of his own urine (he tells us it is so) and squirts some of that over more mercury, and he rubs and rubs a sheet again with his palm. I’ve lost the thread of his demonstration. He has three workers who tend the primordial mills and sifters. They look at us, blank-eyed, as their boss excitedly, hoarsely, explains his trade. Something has happened to his face, his eyes are too large. Each week, out of it all, comes a nugget of poor gold the size of a lima bean. Six thousand pesos, or twelve bucks to us at the exchange rate. The owner’s family lives on what’s left after the employees are paid. Now he wipes his hands a last time with the crusty cloth and leads us outside to the “souvenir shop,” a long table with dull-colored rocks and strange tin trinkets. He encourages us, gently, shyly, to buy, and I give him some money for a couple of small metal things whose purposes are mysterious to me. He is very happy. His little daughter comes up to him, and he takes her tiny, goggle-eyed face in his quicksilvered hands and kisses her head.

Santiago

Raúl Zurita

Raúl Zurita says he doesn’t like abstract poetry. A door is a door. I imagine that being tortured might incline a surviving poet toward the tangible world. He says that in those days of brutality and distrust and terror, the reign of Pinochet, he began to imagine writing poems in the sky, on the faces of cliffs, in the desert. A city poet nearly all of his life, he began to dream of nature. He started to imagine that he might fight sadistic force with poems as insubstantial as contrails in the air over a city.

Zurita, elegant but thoroughly unpretentious, soft spoken, fully attentive as listener, grimaces and shifts slightly every so often. He’s left the hospital early, two days after kidney stone surgery, so to be here.

His words NEITHER SHAME NOR FEAR bulldozed into the sand at the skirt of a mountain, are gradually fading away, joining thousands of men, women, and children who disappeared in fear and pain during the Pinochet years. But schoolchildren in the closest desert pueblo come with shovels and turn over the ground inside the letters, refreshing them. And so new editions of the poem are published in situ, invigorating the relationship between republic and republication.

Desert Poem

He’s written what are perhaps the most massively scaled poems ever created. He’s done this with earth-moving equipment and with smoke-trailing aircraft. I tell him the aerial photo of his Atacama text, NI PENA NI MIEDO, the words one kilometer tall and three kilometers long, larger than the Nazca plain drawings, had stunned me — that the proffering of its gesture in a time of terror struck me as one of the most moving and powerful instances of artistic commitment I had ever seen. What I have been wondering, I ask him, with a surfeit of self-conscious cultural qualification, is if Robert Smithson had been any sort of influence in that project? He smiles and nods. “Yes,” he says. “I know that in some way the spirit of Spiral Jetty is inside the Atacama words.”

Zurita has a remarkable face. His nose, expressive as a collie’s, marks him for melancholy. His grandmother was Italian and he talks with his hands — they stretch out behind him or reach over to touch me on the leg, the shoulder. His face, tense with gravitas, suddenly zooms toward me, releasing itself into a smile, a laugh that issues now from the whole of his face, not only the eyes and mouth. He talks of the acantilado project, his plan to inscribe a poem into the cliff face on Chile’s coast. Of his recent kidney operation — he still has four stones. The operation, it was nothing, but he doesn’t look comfortable on the hard wooden seat at the small breakfast table in The Orly Hotel.

Zurita’s Acantilado[3]

A man in dark suit peers at us over his copy of El Mercurio. The headline reads: “U.S. Denies Torture at Guantánamo.”

More than anything, Zurita emits warmth. As if there were honeysuckle under his skin. We embrace goodbye and I turn down the invitation to lunch at his house. I am at the end of my capacity to concentrate.

The waiter shoos the beggar away before he can get to us. He looks back, staring at me, caked white-hair, sun-leathered face, holding his hand out behind him as he’s pushed out the door.

In the Plaza de Armas, the cannon explosion sends shockwaves through my shirt, the pigeons whoosh into the air like a spadeful of exploding fists. A little girl with a giraffe balloon grips her mother’s hand.

Poets from two-dozen countries take the stage over the course of a couple days. It’s Chile-Poesía, one of the major Latin American literary festivals. F reads a poem in English, and the translator reads from the Mexican edition of F’s book. He’s quite good, this translator/reader. In fact, on this day, he reads quite a bit more passionately than F. There is loud applause from the large, eclectic crowd in the Plaza de Armas. That night, at a party, I talk pleasantly with Bei Dao, the only sober poet, it seems, in Chile tonight. “Where is that goddamned tyrannical pirate Paul Muldoon!?” a writer from Bolivia bellows, startling everyone. As the Bolivian has been sitting beside Bei Dao in a silent stupor for half an hour or more, his sudden question seems to have erupted from a dream.

Dubious, the taxi driver, elbow over seat, begins to back down the unlit street, mumbling, and it is more comfortable — and perhaps safer-- for us to twist awkwardly and look through the rear window than to face his backward-turned, grimacing face. There is no address on the door, but we get out and know as soon as we walk in that we have found it: the no-name bar where Foro de Poesía, a loose group of young experimental artists and writers, fall together. A fabulous electronic musician and Rimbaud look-alike, Gregorio Fonten, is singing his hallucinatory, corrosive ballad “Este Es” on the piano. As soon as he finishes and takes a quick bow, four young poets take the mikes and together read an intricately orchestrated poem for multiple voices. No sooner do they finish than a skinny boy with a video camera begins to move around the stage contorting himself, his image projected onto a screen, while he improvises a sound poem that extends, it seems, by logarithms, the sounds possible for a human mouth to produce. A woman projects onto another screen an interactive digital sequence. The quick pacing and the variety of acts is amphetaminate.

Foro de Poesia

And then someone introduces Clemente Padin, the great Uruguayan visual poet. He is along in years now, comes slowly to the stage, talks quietly, movingly, about the time of dictatorship in the countries of the southern cone. He recalls fellow poets who were tortured and disappeared. He talks about concrete poetry and Mail Art as a key component of cultural resistance in Uruguay and Argentina during the 70s. A young member of Foro de Poesía moves around Padin, takes close-up, digital camera shots of the poet's face and of his hands, clasped behind his back. Afterwards, F and I go over to introduce ourselves. I'd been in fairly extensive correspondence with Padin years back, so this chance meeting is a delight to us both. We talk about the Montevideo of my youth and how things have changed, about the recent victory of the left Frente Amplio, about Padin's associations with Fluxus and Noigandres, about who's on top now in Uruguayan soccer. It's a pleasant chat. The younger Chilean poets are gathered around, taking it in. Padin is legendary, a hero to them.

Isla Negra

Forrest Gander at the Wishing Well at Parra’s Studio

The bus lets us off. Classic comic scene: two travel-bedraggled strangers on a dusty road looking in either direction for a sign. K miraculously spots a restaurant and we drag our luggage through the tawny dirt toward Restaurant Veinte Poemas de Amor. How, now that we’ve come all this way without his address or any contact information, are we going to find Nicanor Parra, the 91 year old poet, the famous author of the Anti-Poems? We order lunch and glance idly at the folk art on the wall. One painting, decorated with shells, is a simplified map of Isla Negra. Below a square house on the main road, the artist has written Neruda. At the end of the road that curves along the boundary river, another house--

with a tiny orange car parked outside it — is labeled Parra!

We are the only guests at a hostel called La Casa Azul. The owner is gone, but her friend, an Argentinian painter, shows us to our room and gives us a cursory tour of the kitchen where we can make coffee and find oranges. Yes, yes, he knows Parra. In fact, Parra’s writing studio is just up the road, he can show us. But Parra doesn’t stay in Isla Negra. He lives in a house two towns away. Gathering our flagging energy, we trudge down to the main street to bargain with a taxi driver. Yes, yes, he knows Parra, knows the town where he lives, sure. It’s only a twenty minute ride. When we get there, the taxi driver slows down to ask the first person he sees where Nicanor Parra lives. With those directions, he takes us directly to the house, butted against the sea. We leap out with books we hope Parra will sign, with a tee-shirt from New Directions, his U.S. publisher, and with a note, in case he isn’t there, explaining that we are fans who have come this long way hoping just to meet him briefly and that if he wants to see us, he can leave a message at La Casa Azul in Isla Negra. The girl who answers my knock sticks her head out from behind the door and tells me that no, we cannot see Parra. Is she sure. Yes, she is sure. I ask if we can leave our gifts and the note. She takes them, closing the door in the same fluid gesture, and we go back to the taxi and wait, hoping that Parra, who K thinks he glimpsed as the door cracked open, might read the note and step out. No luck. The taxi driver, commiserating, takes us back. At La Casa Azul, we tell the painter we are expecting a call from Nicanor Parra. A call, he says, perplexed. We don’t have a phone here.

We wander down the road from the hotel to Parra’s “Casa del Poeta,” his writing retreat. Gate locked, we hop it. It’s a modest place, with tiled roof, shutters closed and padlocked. In the unkempt yard there’s a weather-beaten tree house for guests, an empty well, two broken chairs, and a rickety little table. Cigarette butts on the ground, the roll-your-own kind. We poke around. Just us, a jackrabbit, and a murder of cawing crows. Not too long from now, after he’s gone, this couple or three acres will no doubt be put, like Neruda’s home, on the register of the country’s historical landmarks. For now, it’s just a boarded up, empty dwelling, an anti-house, waiting.

Kent Johnson at Parra’s Studio

Finally abandoning all hope, as has been written, we decide we might as well have a look at Neruda’s house before it closes, and we walk there and take the tour. The rooms of ship figureheads, the collections of shells, the enormous narwhale tusk, the African masks, the stunning hand-carved furniture, the broad rafters carved with the names of his dead friends. It’s all museum quality. Lived well for a communist, K notes. When we get back to La Casa Azul, darkness is falling. The painter sees us making for our room. Oh, he says in Spanish, Parra came to see you. He drove here alone in his orange Volkswagon and came to the door with some books.

Did he leave the books, a message, anything?

He just said, Tell them that I came.

And that he came while we were doing our tourist duty at the house of his great poetic antagonist, Neruda…

View from Neruda’s House

There is a wonderful poem [The Listeners] by Walter de la Mare about a man who gallops his horse to a ramshackle mansion on a dark night and, when no one responds to his pounding, shouts up at the windows, Tell them that I came. I wonder if Parra, who knows English poetry well, was quoting that poem. There are Chinese poems, too, written by disciples who hiked into the mountains to visit a master and waited and finally left without seeing him. None of the literary precedents, which K and I recall to each other from our bunk beds in the cold, dark room, quite comforts us.

That night, I will have a rare color dream of a slight 91 year-old man, with a great, white lion’s mane, driving the long, snaking roads of the Chilean coast, in an orange VW Beetle.

At last we take ourselves to the good restaurant. A dish of chilled shellfish, called locos, tastes like thumbs. K mistakes the waiter’s strange, serious manner for contempt, although as the night goes on, it becomes clear that he’s merely trying to impress us with an exaggerated professionalism.

I had bought a large, gorgeous book, the cover a stunning black and white photo of Parra holding out his hand, claw-like toward the viewer. His long-awaited translation of King Lear… Books are extremely costly in Chile, and this one came in at close to $40. I’d added it to the pack of things left with the young caretaker who’d shooed us away the previous day, hoping Parra would sign it. “You know,” I mutter, “He didn’t return our books to us when he came by the hotel. Maybe he thought we were making some kind of weird gesture, giving his books back to him. A kind of anti-gift of poetry, or something.” We go back to chewing on our locos.

The next day we are waiting with our luggage on the dusty street for the bus. A pitiful, matted dog with a swollen rat-tail slinks up to K and nudges his calf. K reaches down to pet it, thinks again and freezes, still bent over. The dog has rolled onto its back offering its belly. At the same time, K and I see its black testicular tumor, the size of a tennis ball. It has been chewed wide open, exposing dark pink tissue deep within. The image is so horrifying, such a fast-pitched memento mori, that we remain silent, sitting next to each other, most of the way to Valparaíso.

Valparaíso

The Technicolor Houses of Valparaíso

We are seated across from the bar within a little parenthesis in the wall, an alcove just capacious enough for the tiny table and two chairs. The bartender tells us to be careful not to hit our heads when we stand. I nod Of course and half an hour later, needing the men’s room, I stand and all but knock myself out.

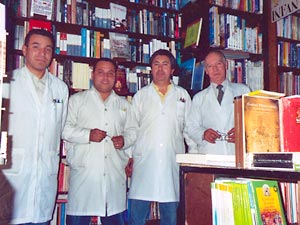

The bar is El Dominó. The next day I learn that this alcove, where we’d sat by chance, was Neruda’s favorite spot there. When the bar was sold some years back, the old owner took with him the autographed photo of the poet that had hung above the little table. I learn this from the elderly owner of a venerable bookstore on Avenida Pedro Montt. I have bought a lovely book titled Neruda Returns to Valparaíso, full of photos. The owner and his staff of three wear white smocks, like doctors. “Oh, yes,” he chuckles, “I drank with Don Pablo at El Dominó on more than one occasion.”

The Booksellers

K takes me to another bar he has reconnoitered while I was sleeping. The proprietor has convinced him, with a few details and several beers, that Neruda was a regular patron here too. The walls are swarming with murals of jazz musicians and creole dancers. K says, I’d like you to meet the bartender: Mr. Primitivo, this is F. F, Señor Primitivo.

Señor Primitivo

It’s the Bar Cinzano, the oldest in Valparaíso, and Chile’s most famous tango venue. Ten days before, working my way toward Andacollo, I’d spent twenty minutes with Don Manuel Fuentealba, one of the country’s most renowned singers. Sixty-something, a handsomer version of Herman Munster, he’d come over on his break to say that not many gringos come to tango evenings at the Cinzano. I told him I’d spent my childhood and adolescence in Montevideo and had been reared on the stuff. He spent the next set crooning classics by Gardel, looking at me almost fixedly from the stage. Tango, when it’s good, can make any man a llorón.

Valparaíso, a pastel city of hills with narrow, cobblestone streets spooling down them. Jungled gullies hemmed by colorful houses of tin, of wood, of native stone. Burned ruins and lovely two story casitas with views of the bay, side by side.

A View of the City

Houses built, literally, one on top of another, into one another. Cobblestone streets are the norm in the cerros. We wander them on Cerros Victoria and Concepción. They wind Calvinoesque, the city more a beehive maze the higher one goes. Wherever one looks, antique marvels: big as a battered four-storied relic there, poised on a drop like some conceptual dare, or small as a bronze hand for knocking, here, on a two-hundred year old door. A knife sharpener spins his wheel outside the café, calling for more blades. A man in rubber boots cranks an organ grinder by the funicular entrance…

We walk past Situationist graffiti, yellow letters on a green wall, that accuses those who talk revolution-- without taking into account quotidian life-- of harboring cadavers in their mouths.

Situationist Graffitti

Indispensable to the city’s daily life, the twenty-six funiculars, rickety boxes that lurch up and down the hills on ancient tracks, are preserved by the government with grants from UNESCO. Preserved in the sense that they seem about to fly apart at their 19th century seams… We clack upward toward the Street of the Yugoslav, and the pitch down the track is steeper than a roller coaster’s. That empty feeling in the groin. A woman of stern visage, on her way home or to work, we don’t ask which, stares at us, biting at a kumquat, yarn and needles sticking out of her bag. However ho-hum it may be to the inhabitants, the city’s dizzying bricolage, on the verge of tumbling into the glorious, aquamarine bay, mesmerizes us.

We serve Viña Tarapacá, he tells us proudly. Ex Zavala, a 2002 Cabernet Savignon. It’s the third best wine in Chile. The guitar player, whose dream is to live in the United States, stops by our table to strum a song written by Violeta Parra, Nicanor’s sister: Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto. My thanks to this life which has given me so much. The refrain cuts through my self-concern, my layers of whining, and sends shivers up my neck.

One of Nicanor Parra’s poems in Antipoems: How to Look Better and Feel Great, newly released by New Directions, reads: “The world needs more Violet.”

Chocolate condoms in the men’s room dispenser. Smell of cat urine in the dirt yard. Each time I pass this alley I think of the Washington zoo.

In the seafood stalls of the mercado, there are astonishing arrays. The horrific congrio with their greyhound heads and snake tails; the giant centolla crabs, impossible beings, and their smaller cousins, the jaivas, in claw-waving heaps — exquisite raw, these last, straight from the shell, with salt and lime. And the wunderkammern display of mollusks: choritos, ostiones, ostras, erizos, machas, picorocos, locos, piures, the last four particularly bizarre and found only in waters of Chile. Especially the piures: black, rocky, forearmed things, orange slime puttying from fissures, weird algae, flotsam, and sea-lice, some still squirming, accreted to the dark carapaces. Piures look like something ripped deep from a camel, after it’s rotted a week in the desert. When boiled, their meat glows brighter than hunting vests. Viscid and steaming in a bowl, they make a budget lunch for the poor. They taste like iodine, go down like phlegm, and are reputed, at large quantities, to enable powerful, multiple orgasms. Chochayuya, a seaweed that looks like a desiccated horse penis, is said to relieve bunions.

Victor Bustamante, owner of the wonderful Librería Iván on the Plaza Aníbal Pinto, spends two hours with me, rummaging in back rooms, looking behind framed old maps propped on high shelves, going up ladders and pulling down antique and recent books by poets of Valparaíso and Viña del Mar. He has the most complete collection in the world, he says, of the region’s poetry, and there is no reason not to believe this. He arranges the books in piles, by “tendencia”: traditional/official; semi-official; experimental/radical. “But,” he apologizes, “I can’t show you the great book of the most radical poet of all Valparaíso and Viña del Mar, Juan Luis Martínez. That book was an edition of one, and it was a box, a large box of pine, and when you opened the cover of this book, you saw it was filled with dirt and sand and pieces of clothing and shoes and animal bones and nails and shells and lots of things. It is titled La Poesía Chilena (Chilean Poetry). It changed everything.”

At Neruda’s house in Valparaíso, next to his writing desk, I examine the cylinders of music behind the player. They are labeled Polka, The Barber of Seville, L’Angelus de la Mer, Las Tribulaciones d’un Pipelet.

The life-sized daguerreotype of a younger Whitman dominates the fourth storey bedroom with panoramic view. He looks out over the bay, one of the roughs, as if still part of a living crowd, as if still with us, generations hence… And here, over a sink the shape of scallop shell, is Neruda’s bathroom mirror. I look into it and my face is there, exactly where his face so often was. Of course, all mysticism and allusion aside, I don’t look a damn bit like him.

Drinking half a bottle of Santa Emiliana Cabernet Sauvignon 2004. The movie about tornados playing in the corner of the restaurant opposite me but not so far off that I can’t read the subtitles.

David Shapiro has urged us to look up members of the Valparaíso School of Architecture, a grouping of experimental architects whose designs, he’s enticingly told us, are similar to the Russian School of Paper Architecture — fantastical, uninhabitable constructions, or else implausible blueprints, never meant to be built. Coming down a steep street on Cerro Victoria, we see behind a fence a two-storied, house-sized box of thick iron girders, nestled tightly between tall, elegantly ruined homes. It looks like the substructure for something built to last ten thousand years. But the network of beams is so closely spaced, the lattice so cramped, there is no possible place for any eventual rooms. There are vines winding around it and wildflowers everywhere all around and within it. Swallows fly through it. We stand there, scratching our heads and laughing, ask a teenager coming down the hill if she knows what it is. She is very shy. “Oh, I don’t know, I guess I never really paid any attention to it. ¿Quién sabe?” Only later, over the bottle of Santa Emiliana at the Bar Cinzano, watching Twister on the heirloom TV, does it occur to us: The Valparaíso School of Architecture!

On Plaza Santomayor, you have to be careful. It looks something like a pedestrian mall, but cars and buses zip up and down on either side of the undifferentiated center of the square, devoted now, post-Pinochet, to large-scale installations of contemporary art. Currently, there is a show of dozens of ten-foot high photographs by various artists, set up on scaffolded pipe frames, each photo given to macabre, mysterious, or erotic (or disturbing articulations of these) displays of the naked body, a number of them perfectly shocking. It is very popular, this show called “Cuerpos Pintados” (Painted Bodies). People wander amidst it, laughing, thoughtfully gazing, chatting: bohemian types, nuns, school kids in uniforms, young men in hard hats, families on outings… The show is smack in front of the imposing baroque edifice that houses the national headquarters of the Chilean Navy, from where a good deal of the dirty war that tortured, killed, and disappeared tens of thousands in the 1970s was directed. A cluster of girls giggles beneath one of the pictures: two towering dwarfs, their penises half as long as their legs, joyously kiss against a backdrop of clouds.

Photography Exhibition

In this back-alley dive we find by accident, visitors’ names have been scribbled with markers and pens across everything — the walls, the cabinets of antiques, the glass windows — and innumerable small photos of patrons have been stuck into every picture frame and mirror, obscuring whatever once appeared there. We are in a shrine celebrating the human desperation to be remembered.

It’s the Casino Social JJ Cruz, owned by Don Suárez Johansen, the antiquities collector I’d met in Horcón!

A vaguely simian man in a baggy suit stares at us, leaves, returns, smiles, approaches us, leaves again, returns and mimes clapping his hands. And then from a shelf of antiques, he picks up two gourds I hadn’t noticed. An accordionist emerges from the back room and sits by the door and begins to play, swaying, and the crazy man shakes the gourds and breaks into song — something about butterflies coming out of your mouth and end-words that rhyme Valparaíso and I adore you. We order another bottle.

I ask the waiter if Don Suarez is in town. “No, no, he called in today, still in Horcón.”

Two young lovers eating a traditional dish of steak over French fries clap at the end of the song.

A darkened cabinet of stopped pocket watches above them.

Putting down the gourds, the singer drops an old envelope on their table and on ours, and winds his way around to every table, greeting those he knows with boisterous exclamations. The air is smoky, the voices loud; the envelope says, Gracias por su valiosa cooperación. We put in a few bills and K asks in a low shout for a tango — the man cups his hand to his ear — K shouts again. The man nods to the accordionist, three generations of a family file in through the door, the musicians launch into a song called El Indio Vígaro, more people keep coming, bottles appear and disappear from our table, the room is packed, the thousands of hand-scrawled names are pulsing on the walls, the multitude of photographs staring fixedly into the shadowy room. I take off my jacket. K’s eyes are slanted, unblinking, he’s mesmerized. We have found our way to the precise, bulls-eye center of a Saturday night in Chile. A camera flashes and flashes again.

The Message on the Medium

Before the cantina door closes and we climb the hill to the rowhouse where the painted screens of two televisions stacked in the yard proclaim Turn Off the TV and Live Life, the Valparaisan night has copied our faces and signed our names to the wall.

Forrest Gander’s author notes page gives more recent information on his work, as does Kent Johnson’s author notes page on his.

Notes

1 Sections of this essay appear, in different form, in the Spring 2006 Conjunctions, an issue devoted to innovative essays, edited by Bradford Morrow.

2 Unferth is Beowulf’s human nemesis in the Old English poem saga

3 Raul Zurita is currently trying to raise attention and funds for the installation of his poem on these cliffs. Anyone interested in helping should contact Zurita or the authors of this essay.

For a concise introduction to the history, geography (a clear map), politics and culture of Chile, see http://geography.about.com/library/cia/blcchile.htm

Copyright Notice: Please respect the fact that this

material is copyright:

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for

any other purpose

This material is copyright © Forrest Gander and Kent Johnson

and Jacket magazine 2006

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/30/chile.html