Back to the James Schuyler  contents list

contents list

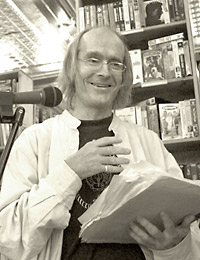

Simon Pettet in conversation with Pam Brown

Simon Pettet. Photo courtesy of www.jonbidwell.com/

Simon Pettet: I knew and revered, James then, Schuyler as a poet and naturally I wanted to read everything he wrote, and I think I simultaneously discovered a run of old Art News in the library and that set me on the trail of wanting to read all his art writing (having already been interested in the art he was writing about) I was particularly interested in a perceived ephemera but also an aesthetic chops that he couldn’t help but display (not the least, coming off his youthful experience in Florence), so, “art history”, and, then, what’s there in his poetry, a very practiced eye. And his language, even tho’ it was journalist work, particularly because it was journalist work, was always interesting, a poet’s pithy summary (and always generous).

Simon Pettet: I began by methodically xeroxing and reading each and every piece, cutting the prose out and pasting it (Elmer’s Glue) onto individual sheets. And then, this was still, albeit the twilight of that age, the fabled typewriter-age, I typed each page up (all too often needing the white-out and despairing and typing all over again!)

I informed Jimmy, as he now was, early on (of my obsession and enthusiasm). We would talk often in his room in the Chelsea hotel, meeting pretty regularly, once a week, chatting both there and round the corner at some local boîte — Sometimes we’d take a cab uptown to the galleries.

One particularly memorable (and longer) jaunt was accompanying him and Darragh Park to the Courbet show at the Brooklyn Museum. Jimmy also loved the drawings shows at the Morgan Library.

As I recount in the introduction to Selected Art Writings, he began dismissive, “Oh, skeletons in my closet”. But soon came around and was, as we worked on it together, 100 per cent enthusiastic about the book. He would direct me to out-of-print pieces by him. He also, at the end there, wouldn’t let me have his piece on the sculptor Andrew Lord (“that’s for my next book of poems”!). His, as I also recount in my introduction, was a rigorous eye and so he carefully “exercised his veto privilege”, cutting down from what was approximately a 500 page manuscript. I felt fortunate, we finished all our editorial decisions (book finished, business taken-care-of) shortly before he died.

Simon Pettet: Pam, I’m not so good at chronologies and dates, find that the years go by (surprise!) a little too fast — I first met Jimmy through my friend Helena Hughes, who was his secretary and assistant, also Eileen Myles and Tom Carey who were also friends… and of course Ted Berrigan. This would indeed be the mid 80s. Like I say, I’d visit with him often in his rooms in the Chelsea. He was a great Anglophile and would pass on to me occasional mystery novels and his last-week’s copy of the TLS (Times Literary Supplement). We, or at least I, would talk.

Simon Pettet: Both — and the absolute wonderful interpenetration of both.

Simon Pettet: “reflecting”?, “a scene”? — well, Schuyler has it best in that oft-quoted line from his in Don Allen’s, New American Poetry anthology — “New York poets, except perhaps the color blind, are affected most by the floods of paint in whose crashing surf we all scramble”.

New York poets and painting — well, it’s like love and marriage, horse and carriage, how does that song go? — still.

Simon Pettet: Au contraire. There’s that bon mot of JS — “It’s really great being a poet. You write a poem, and have the rest of the day to yourself”! — He’s joking of course; there is that “kind of compulsion”, you’re a poet 24 hours — tho’ it doesn’t take that long to actually write the poem, and there is, furthermore, something, hopefully, organic about practice.

“If it won’t come, it won’t come… ”. On the other hand, if it will come… (I remember him writing ‘A Few Days’, or, for that matter, ‘The Morning of the Poem’). I think he both feared being fallow, and wrote often with great exuberance, finally trusting his own productivity or lack of it.

He was indeed a “chronicler of a detailed quotidian”. I think particularly in this context of his extraordinary weather journals. What to one with lesser skills (eye, attention) would be just hum-ho — how to describe the precise salmon-pink in the morning sky, say, or the way the light looks, over here, and over there.

In the letters and the diaries, there’s an extraordinary interest coming from wanting to say it (having to say it) that “the writing gives an impression of having been written with ease” is of course his supreme accomplishment, that great transparency, which, of course, is got not with sweat and toil (although not without sweat and toil!)

I think that deftness, that light-ness (what makes the poems so readable!) is something other poets envy (“Boy, I wish I could do that…”), as if it were something not intrinsic to the poet himself, as if it were not the result of a singularly (remarkably) distinctive ear — and a wit (refusal to take oneself too seriously).

Simon Pettet: I’m naturally encyclopaedic and curious, tending to exhaustive, and, typically with Jimmy — how… revealing, and finally, useful, to methodically annotate all the cultural references (writers, artists, books, works of art, allusions to songs, films, etc, that he so liberally, even, it might be argued, exotically, references throughout his oeuvre. And so, I did so, helping Nathan with what would later come to be that substantial who’s-who in the diaries apparatus, and, later, Bill, (“tenacious”, I think he called me), reading/ annotating page-by-page, imagining, just as a template, an utterly ignorant reader (“Joe? Joe who?”) and an almost limitless filling-in-the-blanks (who starred in?, who was the director?, what was the proper name of that movie Jimmy confesses to have watched on tv late last night?, not to mention, the wonderfully eclectic and extraordinary bibliography, what books he was reading, etc etc).

Bill (as Nathan before him) was able to winnow from this and this may have been some help. Editorship, I would argue, well, in my case at least, was a fairly singular (personal) endeavour, but one is able to draw on invaluable practical assistance from all Jimmy’s friends — one, of course, is always happy to do so. See the acknowledgments page.

Then of course if we’re talking of the co-operative process, there is the huge co-operation between editor and subject (in this case, the living author) and my gathering of his texts. He alerts me, for example, as I mention in my introduction, to a number of pieces that I would otherwise not have found.

Simon Pettet: Cuts into (yes) but also supports (yes), is complementary, underlines (yes, in the sense of getting me closer and closer to the work), undermines (no, can only assist my own poetry)inspires? (sure, JS is a deeply inspiring [sic] poet — “If only I could write as good as that” — typical response).

Simon Pettet: Flattered, I suppose — but I’m not “James Schuyler’s editor”, just (just?) someone who made (compiled) a book with him.

My perception of myself as a writer? I try not to be too self-conscious.

Simon Pettet: — Bill, I guess my question to you is what are some great stand-out lines for you? — from the Letters?

William Corbett: Simon, the standout phrase is his “I was a fucking sensation” about his reading at DIA. Otherwise a powerful overall impression that came from running a spellcheck on the entire manuscript of the letters. The spellcheck flagged nearly every line. It took me a while to realize that when we write letters, when we are most intensely interested in communicating, we don’t mind rules of spelling and grammar. This has changed, for one, my approach to teaching.

Simon Pettet is the author of Selected Poems and, most recently, More Winnowed Fragments (both from Talisman). English-born, he is a long-time resident of Manhattan. Aside from his work with Schuyler, he published two important books with the photographer, film-maker, Rudy Burckhardt (Talking Pictures and Conversations About Everything) (see Jacket 21). A selection of poems and essays on his work and an interview appear in Jacket 25. He is a Scorpio (like James Schuyler) and happy to be one!

William Corbett in conversation with Pam Brown

William Corbett

William Corbett: James Schuyler’s executor the painter Darragh Park asked me to edit JS’s letters. He did this after the JS memorial at New York’s Poetry Project. I didn’t give it a second’s thought before saying yes. The book did not become a selected until two or three years before it was published in October 2004. For ten years we thought we might be able to publish all 1,400 pages of letters.

William Corbett: I began the project by contacting JS’s correspondents and they — Jane Freilicher, Ron Padgett, John Ashbery, Kenward Elmslie, Joe Brainard, Anne Dunn, etc. — provided me with Xeroxes of the letters they had received. Simultaneously Darragh and I went through some of JS’s old address books and I spent a week at the Mandeville Collection [1] UCSD looking through JS’s archives.

William Corbett: I met JS twice, once at Ann Lauterbach’s NYC apartment at a party for Kenward Elsmlie and Joe Brainard’s book Sung Sex. Nothing but small talk and not much of that as he left early because he feared being trapped in Tribeca where he had always found it difficult to get a cab. I think he also left early because he had a dentist’s appointment the next day. The other time we met was at the reading he did in Melville’s barn behind Arrowhead in Pittsfield, Mass. Michael Gizzi ran that reading series. I’ve written about this reading in a piece that’s in the Denver Quarterly James Schuyler issue and JS wrote about the afternoon in his diary. After the reading about fifteen of us went to dinner. A long table with JS in the middle. He insisted I sit on his right, which flattered me because he announced loudly that this is where he wanted me to sit. Again not much beyond small talk. This time the subject was gardening, and he admitted that he wasn’t the gardener his poems made him out to be. He was very chatty and easy to be with, and it was obvious to me that he liked me as it was obvious to him that I liked him. We made plans to have lunch in New York but that never happened.

William Corbett: Editing JS’s letters to Frank O’Hara went fast because in the thirteen years it took me to edit Just the Thing I learned how to depend on others. Nathan Kernan, who is writing Schuyler’s biography, Anne Porter, Ron Padgett and most of all John Ashbery gave the Schuyler to O’Hara letters invaluable help. Books like this are not made by one person but are the work of many. Once you discover who the many are you go to them with questions and make sure you understand their answers. Then you labor to get what you have learned right in print. With this last I had the help of Michael Gizzi who spent two days with me in Vermont as I read the original letters aloud and he checked them against the typescript.

William Corbett: I doubt that JS wrote except when the spirit moved him or to meet Art News deadlines. Remember that for nearly thirty years of his life he did not hold a job and that he did very little revision. As a poet of conscious/ heightened attention I do think poems “happened” to him. He had, so far as I know, no projects. The ease came from his talent. My feeling is that when a poem happened to him he stayed with the poem until he got it done to his satisfaction.

William Corbett: First reaction was simultanous surprise/ delight/ me? a poem from one of my poet heroes? and soon after a feeling of deep pleasure, calm pleasure. I remember that he told me the poem would appear in The New Yorker without the dedication because TNYER didn’t permit dedications. He apologized for this. When he read at the YMHA in New York he gave them a draft of ‘Yellow Flowers’ to hand out as a keepsake of the reading.

William Corbett: Just the Thing depended on the generosity of many people. My name is on the book, but it really stands for all those mentioned in the acknowledgments. Simon and Nathan first among them because as editors of art writing and diaries they had been their first and answered every question I asked with good grace and alacrity. Simon footnoted most of the book and in doing so went over the top, which was a big help to me because that was my sense of how things should be done. When I actually saw it all written down I realized, swift kick in the butt from Raymond Foye, that footnotes are best terse. In other words Simon gave me a foundation on which I could build. Nathan’s advice was more of the “do it your way” sort, which came at the point that I needed to hear it. He also read and commented on the introduction.

William Corbett: Because I typed roughly a thousand pages of JS’s letters into a computer I became not only familiar with his language but soon saw that letters pay scant attention to rules of spelling and grammar. By their nature they put communication first, and every page of every JS letter set off the spellcheck/ grammar check like crazy. If you want to say ‘Puh-leeze!’ you can’t write ‘please’. As a poet and a teacher of writing I had to think all over again about how best to communicate in the American tongue.

William Corbett: Editing the JS letters is part of who I am as a writer. I don’t rate being a poet above it. In fact, I try not to rate what I do — teacher, art critic, book reviewer, editor — when I am at each thing I better be at my best. I’m proud to have served the work of a writer I love and to have helped put into the world a book of JS for those who love his work.

William Corbett: Simon: In JS’s art writings I have a favorite sentence. It is in his Kline piece — “It is rather like a man who wants to chop down trees but first learns how to untruss a fowl and which way the port goes round.” I’ll bet you have more than one favorite sentence. If you do please quote.

Simon Pettet: JS’s conviction is always of course paramount (tho’ his tentativeness (‘it isn’t raining, snowing, sleeting, slushing,/ yet it is/ doing something”) is critical too. In the Art Writings, I’ve always admired his paean to John Button (it matters not a jot that he was at the time madly in love with him!) — “John Button’s strength is truth, his weakness, beauty, his gift to know what is emblematic of his most profoundly engaged feelings, and to paint it when he sees it”.

I also still laugh each time I read that sentence about the painter (let’s not name him) with “his own pastry-chef way of working gouache” — “This year he has addressed himself to the tondo, and even Rome’s most dashing confectioners might think twice before emulating works like ‘Pink Violets!’

You’re right. There’s (just) two — but there’s so many! Jimmy’s wonderful combination of wit and accuracy and erudition.

William Corbett: Nathan: Can you name a few biographies that you will use as models of what to do and what not to do in writing the JS bio and tell why they are models?

Nathan Kernan: Not exactly models, except in very general ways, more like inspirations: some literary biographies that I remember loving include: Sybille Bedford’s bio of Huxley; George Painter’s of Proust; Leon Edel’s of James; Hillary Spurling’s of Ivy Compton-Burnett; R.W.B. Lewis’s of Wharton; Richard Ellmans’s of Wilde. No doubt I am reaching above myself! I can’t say that I have read too many biographies lately, which is odd, maybe good.

I loved Jean Stein’s Edie , but believe that it has been a bad influence on biography since then. Also Naifeh and White’s (are those their names?) Pollock. Both, of course, relied on unmediated quotes from various people, which sometimes conflicted. It is very tempting, when one has interviewed many people, just to let them tell the story, without trying to really sort it out for oneself. Even in Gooch’s O’Hara or Spring’s Porter — both very impressive, fine books, which we have all come to depend upon — I sense at times a lack of authorial center. Perhaps that is what the modernist, or post-modernist, biography should be, but I prefer a more old-fashioned narrative. I also hope to write a book that is shorter than many biographies seem to be nowadays.

William Corbett is a poet living in Boston and teaching at MIT. He edited Just the Thing: Selected Letters of James Schuyler (Turtle Point Press, 2004).

Nathan Kernan in conversation with Pam Brown

Nathan Kernan: I met Jimmy in about 1989 and we were good friends in the last year or so of his life. After he died I approached the Estate (Darragh Park, Raymond Foye and Tom Carey are the three literary executors) about writing a biography. They were not ready to agree to that, but offered to let me edit his Diary instead. At that time I was working in an art gallery and writing prose and poetry in my spare time. This was a great honor and opportunity for me, and very generous and risky of them to take a chance on a completely unknown writer/ editor.

Nathan Kernan: I began the project by taking time off work one afternoon to meet Darragh Park in Central Park where he handed me a stack of xeroxed pages. These were copies of the original Diary typescript and manuscript, then as now in the Schuyler Archives at the University of California San Diego. Schuyler’s “Diaries” were mostly not written in bound books but were single-page (mostly) typewritten entries. My first step was to transcribe these sheets. They were mostly dated and in order, as I remember, but I probably had to rearrange them a bit too, and in a couple of places guess at the dates.

About six months or a year later I quit my job at the gallery and was able to devote more time to the Diary.

Nathan Kernan: I moved to New York in 1977 and got a job in an art gallery about a year later. Through the gallery I met some poets and many artists, one of whom was Anne Dunn, the wife of the English painter Rodrigo Moynihan, whom we showed at the gallery (Robert Miller). I immediately bonded with Anne and we become good friends. Through her, and another friend, the painter Carey Marvin, I met Joe Brainard, who had been a kind of hero of mine since high-school, and he became a good friend. Sometime in the 80s I first read Schuyler’s poems, which I loved. Anne was a good friend of his and it is her drawing on the cover of The Morning Of The Poem. Though I first “met” James Schuyler at a party for Anne’s son, Danny Moynihan at John Ashbery’s apartment, that was just a brief encounter. It was Anne who arranged that we should meet for dinner with her, and that was wonderful. Then Joe started inviting Jimmy and me to dinner together, at restaurants near the Chelsea, and

eventually Jimmy and I just got into a habit of meeting and going out to dinner ourselves. Lots of meals, at “Twigs” on 8th Avenue, Chelsea Central (Jimmy’s favorite at that time) on 10th Avenue, etc. A few times we met at the Metropolitan Museum after work (mine) on Friday. Once or twice we ate oyster stew at the Oyster Bar in Grand Central, and he showed me the “whispering gallery” outside it. We saw each other quite a lot and it seemed like we had known each other for years, but in fact our real friendship was only for about one year, and then he died.

Nathan Kernan: The whispering gallery — don’t know if it’s really called that — is a sort of large square domed vestibule in front of the entrance to the Oyster Bar in Grand Central. If someone stands in one corner facing the walls and speaks in a low tone, someone in the corner diagonally opposite can hear it quite distinctly, while someone standing, say, in the middle, will not. Based I guess on the one in the Palazzo at Caprarola in Italy and probably others elsewhere.

Nathan Kernan: Of course he didn’t work “for most of his waking hours”, but maybe you mean that the work gives the impression that any activity of any waking hour is worth trying to write about. That is an impression the poems could give, yes.

There is a difference between letting poems “happen to” one and writing with “ease.” Schuyler’s poems can give an impression of having been easy to write but that is a superficial impression. A Pollock or a de Kooning can look “easy” too. Schuyler’s ability to let a poem “happen to” him is a skill, or a gift, or in fact a kind of genius. In addition to great verbal skill, I think it requires a particular state of mind, something like disciplined, self-forgetting attentiveness. Maybe it’s something like Wordsworth’s “wise passiveness” or what painter Joan Mitchell called making herself “available to” herself when she paints.

Nathan Kernan: Bill Corbett sent me a manuscript of the Letters, with his footnotes, at an early stage, when it was still going to be the Complete (or nearly so). I sent back 25 pages of suggestions, queries and corrections, some of which he found more valuable than others, of course. In trying to be so thorough I was partly trying to live up to Simon Pettet’s incredibly generous, informed and detailed response to the manuscript of the Diary and its notes that I sent him in 1996. But mainly I was trying to repay Bill’s own generosity and support over the years, which included his inviting me to stay five days in his house in 1994 or thereabouts to read and make notes on the letters he had collected, which was a huge help to me in compiling the Chronology for the Diary. He further helped and supported me at every stage of the book, including organizing and introducing readings from the Diary in New York and Boston. As he continues to support so many other poets and artists through Pressed Wafer and in other ways.

Nathan Kernan: I am a much more “occasional” poet than either Bill or Simon. I would

guess that editing Schuyler has both supported and cut into, inspired and been discouraging for, my own poetry writing in about equal measures. On the whole it has probably been a help.

Nathan Kernan: I don’t really think of myself in that possessive way as “Schuyler’s editor” and would not want others to think of me so. After all there are so many of us. Which makes me ask: shouldn’t Jonathan Galassi and Michael Di Capua be part of this discussion too? They edited the poetry, after all, which is what it is all about. Plus Michael had the temerity to turn down A Few Days, which would be interesting to hear about.

Nathan Kernan: Bill and Simon, is there some other poet whose “peripheral” writings (letters, prose, etc,) you think are especially due for discovery via publication? And would you like to work on them?

Bill Corbett: I have one letter from Philip Whalen. It’s the size of a placemat, handwritten, hand colored and with a drawing or two in the text. I’d gladly edit his letters. John Wieners? I wonder how many letters there are. Jack Gilbert? Letters but probably little else.

Simon Pettet: I notice your placement of parentheses on peripheral, indicating — I agree — that there is something limiting about hierarchies.Was Rudy Burckhardt, say, a photographer or painter? or both?and does it matter? (John Ashbery memorably called him ‘a jack of all trades and master of several’) — and I note here in passing that Jimmy Schuyler took some beautiful photographs. I’m always (isn’t everyone?) interested in the whole oeuvre of any and all the writers (poets) that I read and love. So this becomes a question about great unpublished books (by poets).

And if I propose them, would I like to work on them?

Of course I would! (and get paid too!)

I think there should be a book that gathers together Jimmy Schuyler’s Interviews.

I think there should be more collections of poets’ interviews.

I like to hear and read intelligent poets talk.

Nathan Kernan, born in 1950, is the author of Poems with lithographs by Joan Mitchell (Tyler Graphics, 1993). He edited The Diary of James Schuyler (Black Sparrow Press, 1997). Nathan Kernan writes art criticism for various journals including Art in America and he is currently writing a biography of James Schuyler.

Note [1] James Schuyler’s manuscripts are held at the Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego.