JACKET INTERVIEW

Bill Berkson

in conversation with

Robert Glück

25 August 2005, in Robert Glück’s kitchen, San Francisco

Bill Berkson is a poet, art critic and professor of Liberal Arts at the San Francisco Art Institute.

This conversation was originally commissioned by the San Francisco Art Institute, which published a much-reduced version in the in-house magazine SFAI Magazine.It is 4,300 words or about 12 printed pages long

¶ Robert Glück: Are you ready for your close-up, Mr. Berkson?

Bill Berkson: Yes.

¶ Robert Glück: My first impulse is to start at the beginning, but instead, let’s start in the middle. A glance at your bio conveys the picture that you are a citizen of both coasts, the East and the West. How did you negotiate that and how has it affected your writing? What is the poem that belongs on both coasts?

Bill Berkson: The Iliad, maybe. Yes, I’ve been here for 35 years, I still say “out here.”

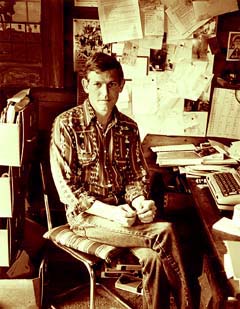

Bill Berkson, Bolinas, May 1985, Photo by John Tranter

¶ Robert Glück: When I was entering the scene here, Bolinas was like New York School West. Lewis Warsh was directing the poetry series at Intersection, Lewis MacAdams headed the Poetry Center. So there was a strong sense of the New York School coming to California. That was recognized and felt and looked at by the local poets. I was already in love with the glamour and energy of the New York scene. I’m curious to know how it was for you?

You mean coming to Bolinas?

¶ And becoming a citizen of the West Coast. You have given a lot of your life to institutions here.

There was the shock, sometime after my 60th birthday, of realizing that I had slipped over a line and spent more than half my life in California. To the extent that I still say “out here,” I still consider myself as a New Yorker. I lived in Bolinas, I was kind of a counter-culture country gentleman for 23 years. You could say it was kind of like a marriage of the resident Bay Area poetics — people who had spun out to Bolinas in the Duncan / Spicer Diaspora — and poets associated with the New York School. How much time did those supposedly New York poets really spend in New York? Tom Clark, for one, who was from Chicago, schooled in Michigan, went to London, touched down in New York, got married at St. Marks Church and left for California.

¶ My sense is that different poetics did not keep people apart.

No, that’s the nice part. The community, so to speak, was so various in Bolinas that when we got together as poets we would talk about firewood and septic tanks. When I asked Larry Kearny, who was then full of residual Spicer attitude, what Jack Spicer was like he said, he said, “He was the most serious man I’ve ever known.” A very un-New York evaluation. As in any rural setting, daily life got very daily. Happily, there was no unifying poetics.

What could be farther from the New York School than the Spicer/ Duncan circle — with their vatic utterance and their metaphysics? At the same time, you can look at individual poems and see overlap. Maybe that’s just the times.

Yes. We had the pleasure of Phillip Whalen’s being there too, along with Mr. Ecumenical himself, Don Allen.

¶ Ecumenical but also withheld. You weren’t going to get much light out of Don.

“Asp-ish as ever” is how Jimmy Schuyler described him when Jimmy visited. Yes, but it’s just funny to think that here in the mini-Melting Pot of Bolinas was the man who did The New American Poetry, which included all these different vectors.

¶ And of course Creeley was there for a while, and Bob Grenier, both of them were my teachers.

There were a lot of people who came and stayed. The New York School to begin with is an absurd designation. Even for the first generation New York School, Ashbery, Koch, and O’Hara and Schuyler had in common, if nothing else, a basic, and very sophisticated, reading list and an attitude about keeping their otherwise very different poems light and fast and airy, or as O’Hara said about “Second Avenue,” “high and dry.”

Bill Berkson at age 19

But then afterwards, what happened was really the New American Poetry. Poets from dissimilar backgrounds and with different interests came together according to how they read the prior generation or two. For example, Jim Gustafson from Detroit, Tom Clark from Chicago, some like Joanne Kyger in the Bay Area, all had read the little magazines and Allen’s anthology. As a young poet your first hit might be O’Hara in New York, but next you’d read Creeley, John Wieners, then Ashbery, and any number of people from other places under different affiliations in that book. The great thing that happened to our generation was that each of us had the opportunity to make a personal meld according to taste and necessity.

¶

There’s a historicizing that isolates different groups, but if you go back and look at people’s letters, and who they are seeing, what they are talking about, there’s so much more overlap than the MLA papers that divide poets into schools, the New York School, Black Mountain, or whatever.

Then, who were you melding with?

The names that I just mentioned are pretty close to representing what happened to me. First of all, even for a New Yorker, for example, at the end of the ‘50s, being the age I was, I headed off to college, having graduated from high school in ‘57.

¶ You grew up in Manhattan?

I grew up in Manhattan.

¶ When you said, back there you mean ...

Back east.

¶ As you were saying, some people came to New York after they grew up, but you were there in the first place.

And then I could have gone anywhere. After all, The New American Poetry had not appeared yet. In 1958, I thought all the excitement was in San Francisco because of the San Francisco issue of Evergreen Review and Kerouac’s The Subterraneans. I came out to San Francisco that Thanksgiving with my parents, who had business out here, and I wanted to get a job on the San Francisco Chronicle on the police beat. Also I wanted to find the Beat Generation and I went to places I’d heard about and asking completely dumb questions like, is Jack Kerouac here?

¶ I’m so glad to hear that. That’s just what I did — except I went from California to New York.

And somebody, I think it was Knute Stiles, the bartender at The Place, said, they’re all in New York. It’s like I trucked 3000 miles to find this dream that was really in my backyard.

¶ Were you writing like Ginsberg and Kerouac?

Oh sure, Yeah, and mainly like [Gregory] Corso.

¶ That was a question of mine, how did you, your first concept of being a poet, what was that?

My first concept was T.S. Eliot.

¶ Well, your second concept, the contemporary one.

Yes, the San Francisco issue of Evergreen Review came out, and with it a recording, The image of being a poet included there was the photograph, probably by Harry Redl, of Ginsberg very wide eyed leaning forward with a cigarette between his fingers, As a teenager I looked at that photograph for hours and listened to him read Howl. Then as it happened, the prospect begins to become clearer to me that something is going on in the world and in my life. My father died and instantly I left Brown and returned to New York. I have to wait a semester before enrolling at Columbia, so I go to the New School for Social Research where I take a poetry workshop because there is one and it happens to be with Kenneth Koch. I go to his class armed with some poems, about which he’s encouraging. Then, a couple of classes go by and I say in class, well what about Howl? And Kenneth allows as how Howl is a very powerful poem but after all, all that noise about “the best minds of my generation” and so on — the same generation as Kenneth, you see — is rather silly and exaggerated. This helped balance my view of things somewhat.

¶ It’s an interesting moment when that happens. Sometimes my undergrads practically memorize Bukowski. I say, Why do you like him? And they say, He writes about life the way it really is. So, I start quizzing them about their experience and it doesn’t resemble what he writes about in the slightest. So real life must be happening elsewhere.

They relate to a life of marginalized suffering. It’s one thing to read the poems and respect them and it’s another thing to say I want to live this glamorous life of dissolution. What is the attraction of that? I don’t think that anybody became a junkie reading Naked Lunch. But junkies might particularly enjoy it for the recognition.

¶ True. One looks for authenticity that one can recognize — that’s what Koch was saying.

L-R: standing, Patsy Southgate, Bill Berkson, John Ashbery; seated, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch.

Frank O’Hara’s loft, 1964. Photograph: Mario Schifano.

So then I got my introduction, fast and marvelous, via Kenneth’s teaching. He kept his poems in the background. But he was very forthcoming about O’Hara and Ashbery and also the connection with painting, which wasn’t unique to New York. I just read a wonderful interview with Robert Duncan about the importance of painting for his work — and not just Jess’s paintings, but what was contemporary for him, generally.

¶ Oh yes, there was the same heated relationship between poets and artists “out here,” including poets writing reviews for the art press, like Art Issues and Artweek. That brings us to you and the New York School.

Okay, the New York School. In 1965 there was a poetry week as part of the Festival of Two World in Spoleto. O’Hara made up the list of the American poets to be invited. Not all his selections were invited; they wouldn’t invite Ginsberg because he had been there a year or two before and taken his clothes off on stage. Maybe half the poets from the U.S. were New York poets, including me. Somebody had the bright idea to invite Stephen Spender to be the master of ceremonies. The first reader was to Barbara Guest, and Spender got up and said, “Barbara Guest belongs to the New York School of poets, whose main distinction, as I see it, is that they all write about painting.” That was all he said about Barbara. So it was a putdown. He communicated to this international audience a sense that to be “New York School” was to be party to a cabal.

¶ Perhaps the antagonism between an English poet and this American team derived from feeling overlooked, because the American avant-garde often jumps over England to France.

Ezra Pound was there, but he was not speaking. He gave a reading from the royal box in the first balcony. He didn’t even read his own poems. He read Marianne Moore’s La Fontaine translations and his son-in-law’s translations of ancient Egyptian love poems and then sat down. Charles Olson thought he would have the ultimate confab with Pound but Pound wasn’t confabbing in those days.

¶ I’ve meditated on the NY School since I was an infant, when I thought I was Frank O’Hara.

Me, too.

¶

The earliest work of yours that I know is in the 1960s anthology The Young American Poets, and there are plenty of poems where you sound exactly as you do now. There is a good deal of consistency. People should never worry about voice. You think you’re sounding like someone else, but you sound exactly like yourself when you look at it ten years later.

I think about the word “you.” How the word “you” is used by the NY School and how it changed things. That very intimate “you.”

As I was reading your poems this morning, in some poems I got an image pile, not a word stack, but a pile of images. Then there’ll be the entrance of the word “you,” which shakes the poem out like a blanket. And suddenly there’s dynamics, relation; it’s no longer a list, a pile, I have to rethink what came before, and what comes after occurs inside a dynamic that actually is pretty clear — if not clear like a story (though some of them are) then clear in the sense of how to frame each image.

There is the “you” as in “you know,” the “you” that is a substitute for “one,” though more intimate than “one.” It’s one trying to extend from the first person singular to the more general case, right? The “you” you encounter in a love poem is otherwise. A lot of O’Hara’s poems turn into love poems at the end via the deft insertion of a “you.” That’s a new you.

¶ Yes, a love poem that withholds the “you” till the end, a last line that will order what comes before.

Yes, yes.

¶ What that “you” does in your poem “Blue Is the Hero” is give the sense of projecting a new narrative on what comes before. We have to rethink it: here are two people, a whole history that enters at the end, but only because it’s placed at the end. You have to project backwards.

In “Blue Is the Hero,” I often wonder who is the hero and who is the “you” that enters at the end: “You are that helicopter.” It’s not self-reflection, an “I” talking to oneself, but it’s not another person, either. When I read it, it feels like I’m talking to a distinct other. It’s a sudden address.

¶ That’s a good term. I like it.

I was reading Richard Holmes’s Sidetracks. He’s a biographer of Romantic poets — Coleridge and Shelley. In an essay on Boswell’s journals he shows Boswell writing of himself “you does” or, recalling the night before, “You was drunk and charming, as ever.” Boswell was writing his journal for himself: “last night you were thus and so,” but the verb changes to “you was.”

¶ The “you” is a very mysterious in these poems, in yours and in others. In some way it foils the muse a little bit: in the moment of the poem it makes a kind of community or presupposes a community of listeners.

It’s a way of immediately engaging the reader, because you’re coming right at the reader, saying “you.” John Ashbery has a poem that begins, “You have been living now for a long time and there’s nothing that you do not know.” And the reader responds: “Are you talking to me?”

¶ That is a very interesting new thing that happened in that time.

It also sets up a kind of narrative. It’s as if you’re jumping into the middle of a narrated relationship.

¶

You know it reminds me of classical poetry. Those letters in verse for example. When I think of that poetry, I see it as open, as part of a group practice.

I also want to observe that you’re extremely polite to the reader. You have a kind of courtly relationship with the reader. And even when gloom is intended, you’ll say no gloom intended. I don’t know whether that’s something you think about, that relationship.

Oh, yeah. I think that that’s where the poetry of the previous generation, really cleared things up. Writers like Kerouac, Ginsberg, O’Hara, where — and I think this is true of the painters too, DeKooning, for example, and Kline — how it’s important to remember that art is a form of social behavior. It’s not exempt from the everyday ethos, and while it may be a superior form of entertainment, it’s not “above.” The aspect of entertainment puts it back in social terms. Why do we dislike some poetry — or art, for that matter? Is there something in the complaint that’s inappropriate? Then one angle of criticism is, how does this play out socially? Allowing for the fact that a work of art is an “as if” real-life situation. It’s “other,” but the terms are grounded in real life.

¶ Are there examples in a work of O’Hara where he criticizes your work?

Well, I sort of do and don’t know what he meant when he took about a poem of mine with the phrase “what I hope is beneath my skin” and wrote this two-liner: “What you hope is beneath your skin/ is beneath your skin.” I’ve never been able to determine whether he meant that to be chiding or encouraging.

Robert Gluck, left, with Bill Berkson, San Francisco, 2005. Photo: Nina Zurier.

¶ I’m a fan of your art criticism — I used to pore over the artforums to learn about what was going on. It was important in my own practice as a writer to know what was happening in visual art. And you are one of the few critics who doesn’t merely stay with a work of art or an artist, or attempt to assign ultimate value, but contextualizes the art and artist, and speaks for them in a kind of brainstorm. And the writing itself is very beautiful. Did you have models?

I have certain, good, desktop models. I freely reach for my Edwin Denby, Whitney Balliett, Baudelaire, or John McPhee when I start writing or whenever I get stuck. I like those who write a companionable criticism. Fairfield Porter, for one, is a very elegant writer, but at the same time, he either won’t or can’t make a continuous argument — not one that is developed logically, anyhow. So his perceptions follow one another, sentence by sentence, seemingly just as they occur, which for me is pretty liberating to attend to.

¶

You recommended James Schuyler to me when I was looking for a model art critic, and he was a great help. I say about my own criticism: I’ll write the topic sentences. Let someone else do the development.

Your vocabulary in your poems is large. Many poets, like George Oppen and Spicer, keep their vocabulary small. Is that a West Coast thing?

I’m often seduced by ten-dollar words. Some of that comes from reading, and some from my background, the indirect language (some might call it euphemistic) of the upper middle class. It’s just in me. Sometimes a word shows up in my critical prose and sometimes in poetry too: a big word that somehow shows up in the writing. I may look askance at it, unsure of what it means but certain that I’ve never used the word before, in either speech or writing. I look it up in the dictionary and, damn!, it’s just right, le mot juste. Now how did that happen? There must be an inner vocabulary monitor that knew it; I didn’t know it, except by osmosis.

¶ It’s an attitude about the surface, but I don’t want to use that word, because what does it mean?

But I think it’s relevant.

¶ I suppose when you make people aware of words, that’s the surface. But then, what are words? Let’s talk about bumping into those words that are indigestible even after you look them up.

There’s the word “sempiternal” in one poem.

¶ There’s that word that has “elastic” in it.

Anelastic.

¶ What a word.

Well, there are poems that tell stories and then there are poems that are more accretions of words and phrases. The language is “out there,” but, although I’m fascinated to write these poems, I’m also distrustful of some of these big words, because they plod in on their little silver feet, a bit too enticingly. Bernadette Mayer always tells me my poems are “packed in.”

¶ Then, does the reader unpack it?

It can be so packed in, intensified that it can’t go on very long at that level of intensity. By the time you get to the end of the page you want to go soak in a bathtub.

¶ But you don’t make these poems look overworked. They’re as fresh and lively as poems in your other modes, poems that look like notation, for example.

Normally what happens is that something gets down and it’s over packed and I air it out.

¶ That’s the final rewriting, isn’t it?

I don’t know what the technique is called, but it’s akin to a painter going back into the painting with white. It’s not just cutting. It often can be adding prepositions and other connective words to give the words some elbowroom.

¶

Matisse said, “If you have a bright color, then put gray around it so the color can breathe.”

Shall I ask you a silly question?

Sure.

¶ Okay, are you true to your astrological sign? Regardless of whether you believe in astrology or not, everybody seems to have a take on whether they’re true to their school.

I’m Virgo. I think so. I’ve got some of the frustrating attributes of Virgo, but in time I think I’ve triumphed over them, or made peace with them. There’s an appropriate rhyme about Virgo that I found and put into a piece of extended prose called “Start Over”: “He’s loyal, devoted/ In fact he’s a jewel/ But critical often/ And that’s a bit cruel.”

¶ I ask this in my classes sometimes at the beginning of term to get students to talk about themselves. And I also ask them to make a list of items, whether the work of an artist, writer, or composer, that they consider essential. What do you consider essential?

Ah, the endlessly revisable list — well, here goes: One of John Ashbery’s books — Rivers and Mountains, probably, or The Tennis Court Oath; Thelonious Monk as complete as you can have; Mozart’s piano sonatas and Divertimento 15; a DeKooning painting; if I had the freedom and money to choose, a Jasper Johns; if there was even more money, the right Vermeer; Balanchine / Stravinsky; Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale.

¶ And, of course, you need a good Romantic in the house . . .

Yes, Keats. Ozu’s Late Spring. Other things by Morton Feldman, Ellington, Basie; Jackson Pollock’s Number One, 1950; Charles Reznikoff’s poems; Kenneth Koch’s poem “Paradiso”; Lee Friedlander; Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection. I look at the Guston drawings in our home all the time. And Alex Katz. I have the Collected Frank O’Hara practically committed to memory. What else? The Kinks, Neil Young, Haydn, Josquin Des Pres, Willie McTell, Sondheim’s Follies . . . and lots more songs I can’t get out of my head. Nick Dorsky is another filmmaker whose work is continually amazing to me. I thank him in Gloria because a lot of the poems in that book come from a little book called 25 Grand View, which was all taken from a little red notebook. During the time when I was still sick, Marie Dern asked me to give her 16 pages for a bookmaking class. I wasn’t writing a lot of poetry, I was casting about and looked at this notebook and began typing it up. Some of the pages were just stray notations, but here and there was a real poem. And this dovetailed with conversations Nick and I were having about outtakes. And I said, “what if you just made one minute films with them? Otherwise, so much marvelous stuff gets left out.” We were talking about what constitutes a really “made” work of art. I dedicated that little book that Marie’s class produced to Nick. I was continuing that conversation, not that it changed his way of working at all.

¶ You just went through a huge health crisis. It would be interesting to hear how it affected your life and work.

Yes, as they say, a so-far-successful lung transplant is a miracle. When I was declared at end-stage emphysema, I understood quite shakily that I was headed for death via respiratory failure, because if I got a serious infection it could have gotten that bad. Before my operation there was this rule of thumb that no one over 55 could withstand the rigors of a lung transplant operation. But the pulmonologist and surgeons determined that at 65 I might be a candidate if I got myself in shape. I was on round-the-clock supplemental oxygen and huffing and puffing, barely able to get down the street. And then, immediately after surgery, I was able to breathe normally. The doctor told me to get right up and walk, and as I stepped into the hospital corridor I noticed that I didn’t have to stop. I don’t have any determined life expectancy — I’m in my 60s, and, like Philip Whalen said, I could croak anytime. When the doctor told me I had end-stage emphysema, I was really shaken. I said, “I’m not prepared to die. I’m not ready. I haven’t finished my work.” How does it feel now? For openers, unless I am just dreaming in the afterlife, I’m aware of this bonus everyday: I’m actually alive. At the same time, I’m determined not to become evangelical. I’ve never been a person to make plans or New Year’s Resolutions.

¶ So your attitude is that you’re trying to resist a change in attitude?

Yes, but I think I had the necessary attitude anyway. The outcome of the surgery and getting my life back was to make me more aware. It’s one thing to know generally how fragile and precious existence is, and it’s another thing to come face to face with the definition of that fact.

¶ Shakespeare says in your favorite play, “Thy life’s a miracle.” How lovely that you’re having a new book [Gloria] from Arion Press. They make the most beautiful books, don’t they?

Yes, I know. I’ll believe it when I see it. That’s the other aspect of resuscitation!

This conversation was originally commissioned by the San Francisco Art Institute, which published a much-reduced version as a promotional brochure for the school.

Bill Berkson is a poet, art critic and professor of Liberal Arts at the San Francisco Art Institute. Of his many books and pamphlets of poetry, the most recent are Fugue State, Serenade and a deluxe edition of Gloria, with etchings by Alex Katz (Arion Press, 2005). He is a corresponding editor for Art in America and a member of the editorial board of Modern Painters.

You can read two poems by Bill Berkson in Jacket # 5.

Robert Glück, San Francisco, 2005

Robert Glück is the author of nine books of poetry and fiction, including two novels, Margery Kempe and Jack the Modernist. His new book of stories, Denny Smith, appeared in February, 2004. Glück was co-director of Small Press Traffic, director of The Poetry Center, and Associate Editor at Lapis Press. His critical articles appeared in The London Times Literary Supplement, Artforum International, Poetics Journal, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, and Nest: A Quarterly of Interior’s, and he prefaced Between Life and Death, a book of paintings by Frank Moore. He teaches at San Francisco State University and he is an editor of Narrativity, a web journal: http://www.sfsu.edu/~poetry/narrativity/

In 2004 Coach House Press published Biting The Error: Writers on Narrative, an anthology edited by Glück, Camille Roy, Mary Berger and Gail Scott.